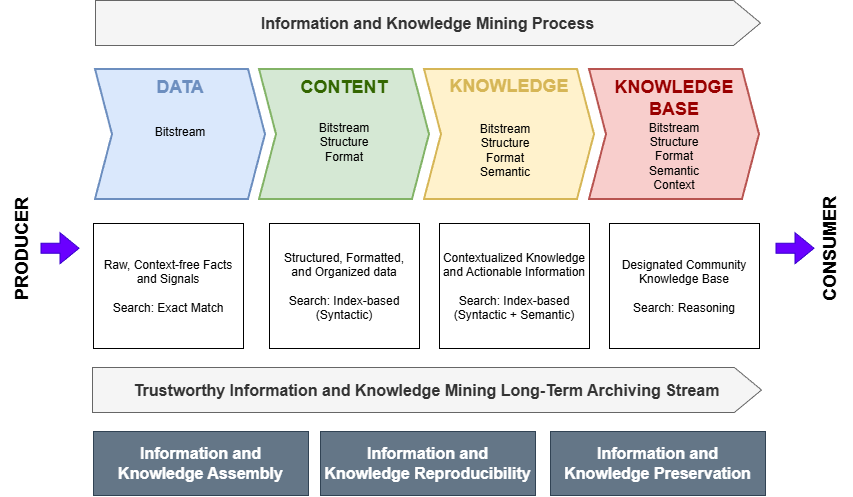

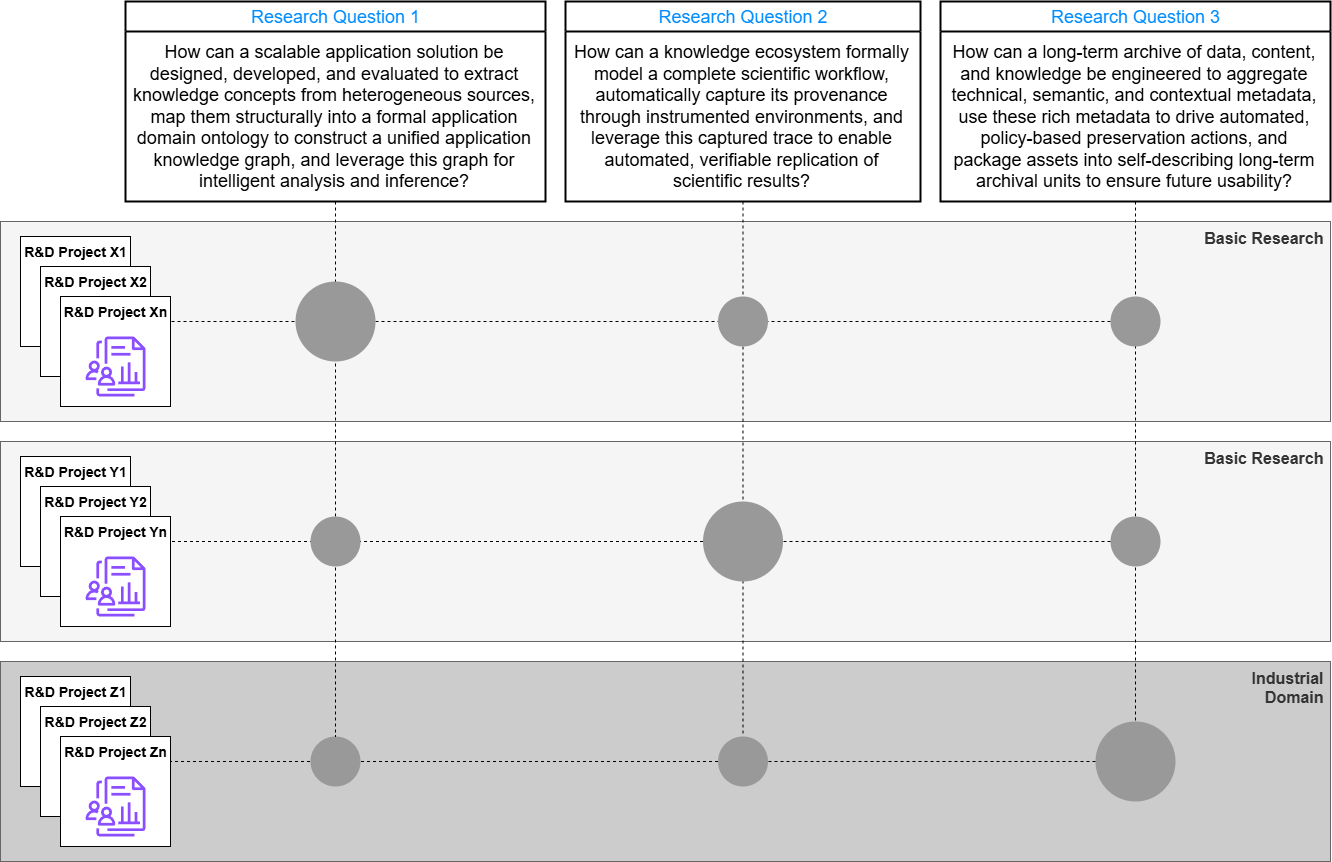

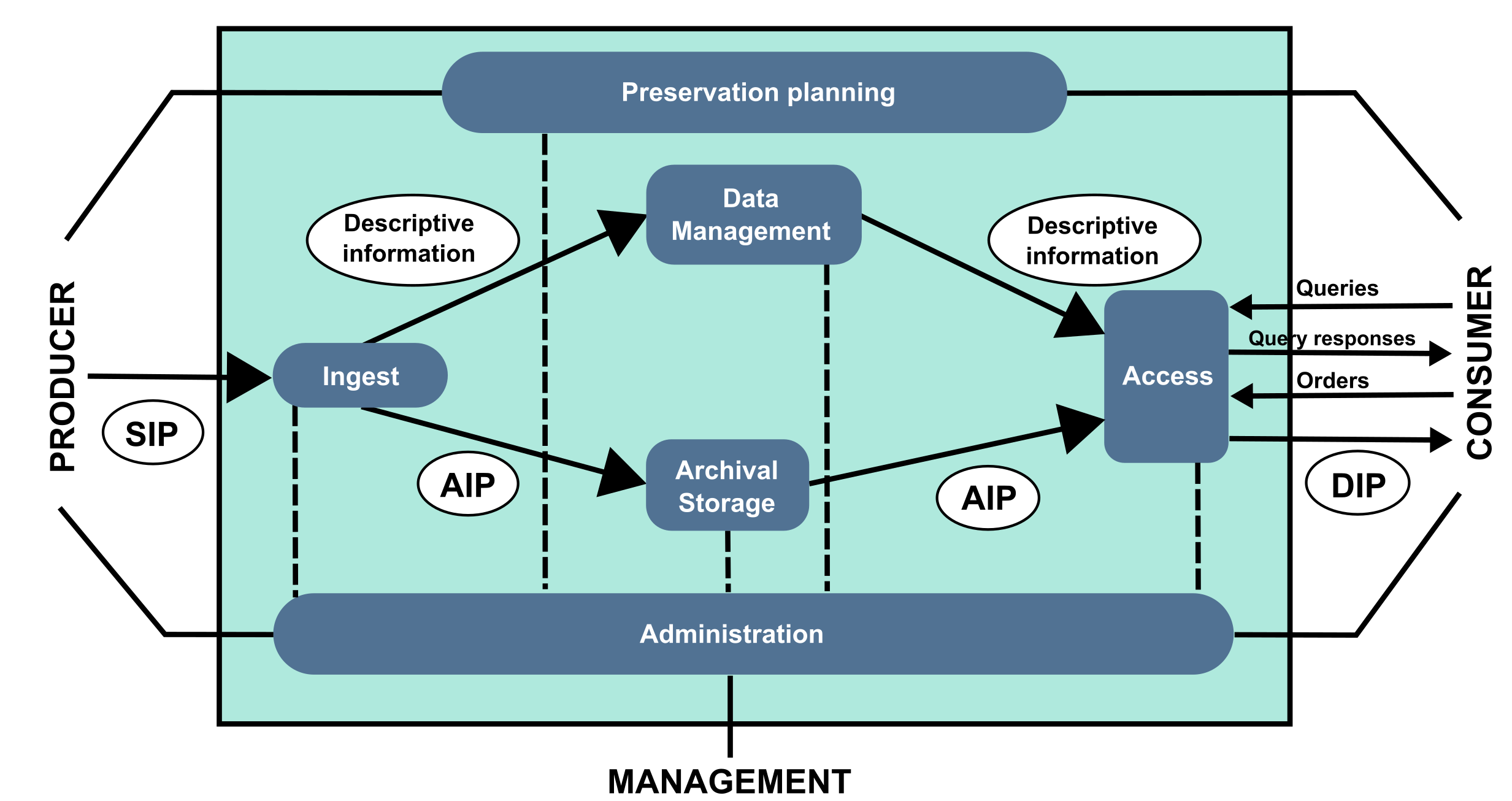

The unprecedented proliferation of digital data presents significant challenges in access, integration, and value creation across all data-intensive sectors. Valuable information is frequently encapsulated within disparate systems, unstructured documents, and heterogeneous formats, creating silos that impede efficient utilization and collaborative decision-making. This paper introduces the Intelligent Knowledge Mining Framework (IKMF), a comprehensive conceptual model designed to bridge the critical gap between dynamic AI-driven analysis and trustworthy long-term preservation. The framework proposes a dual-stream architecture: a horizontal Mining Process that systematically transforms raw data into semantically rich, machine-actionable knowledge, and a parallel Trustworthy Archiving Stream that ensures the integrity, provenance, and computational reproducibility of these assets. By defining a blueprint for this symbiotic relationship, the paper provides a foundational model for transforming static repositories into living ecosystems that facilitate the flow of actionable intelligence from producers to consumers. This paper outlines the motivation, problem statement, and key research questions guiding the research and development of the framework, presents the underlying scientific methodology, and details its conceptual design and modeling.

The contemporary scientific landscape is widely characterized as the fourth paradigm of discovery, an era defined by data-intensive methodologies that complement traditional theory, experimentation, and simulation [1]. This paradigm shift is driven not only by the sheer volume of data being generated but also by its unprecedented velocity, variety, and complexity, which are the defining characteristics of Big Data [2]. For researchers and knowledge workers, this proliferation of data presents both profound opportunities and significant logistical and epistemological challenges. While holding the promise of uncovering insights at a scale previously unimaginable, it also threatens to outpace our capacity to manage, process, and interpret the information we create, potentially leading to a "knowledge glut" where an abundance of data coincides with a poverty of insight. The infrastructure to support this new paradigm often significantly lags, leaving vast potential unrealized.

A primary and pervasive consequence of this infrastructural deficit is the emergence of “data silos,” a phenomenon where valuable datasets become isolated within specific departmental applications, proprietary software systems, incompatible formats, or the local storage of individual researchers [3]. These silos represent more than a mere technical inconvenience; they are fundamental structural and cultural barriers that inhibit scientific progress. For example, a medical research institution’s clinical trial records may remain entirely disconnected from its proteomics laboratory’s mass spectrometry data, preventing holistic analysis. The consequences of such fragmentation are severe and far-reaching. It is a significant contributing factor to the “reproducibility crisis” affecting many scientific fields, as the inability to access original datasets makes it difficult or impossible to verify, replicate, or build upon prior work [4]. Furthermore, data silos lead to an inefficient allocation of resources, as funding is often consumed by redundant data collection and duplicative research efforts [5]. Perhaps most critically, this fragmentation impedes innovation by preventing the cross-disciplinary syntheses that are frequently the source of the most profound scientific breakthroughs.

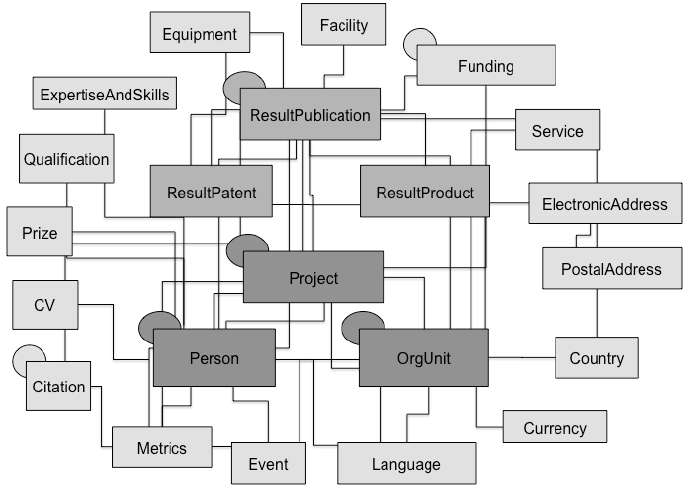

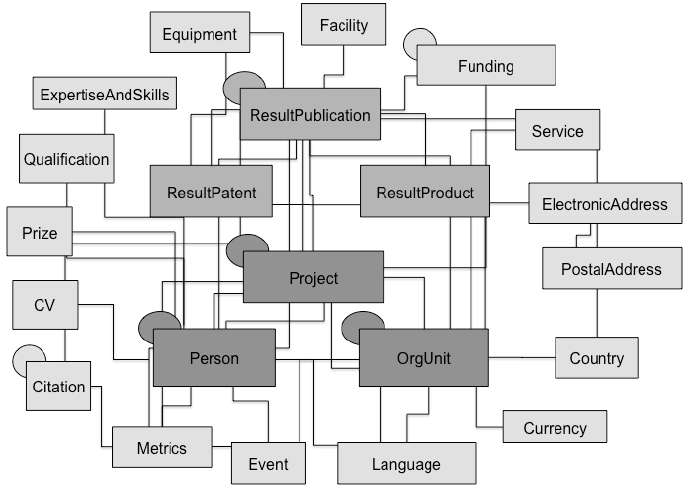

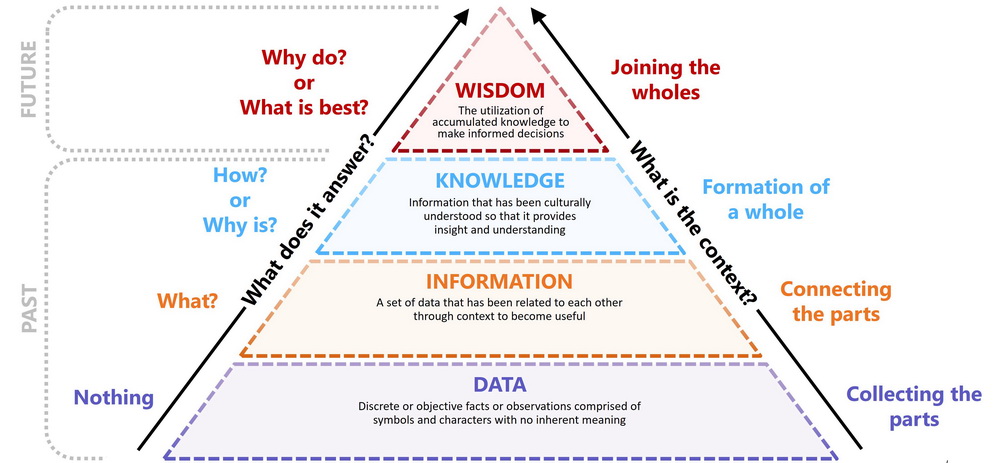

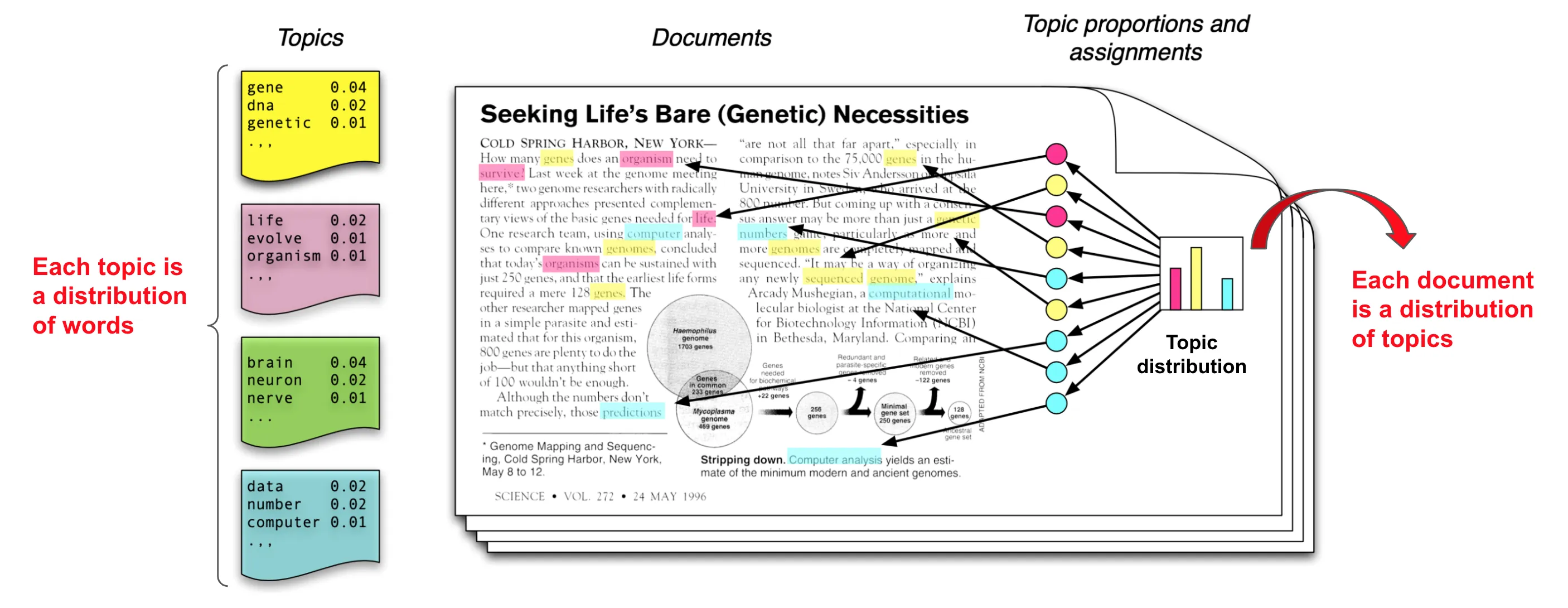

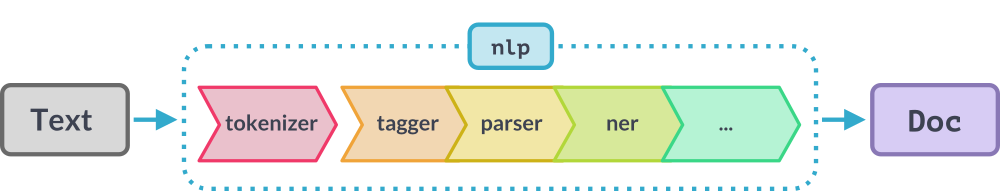

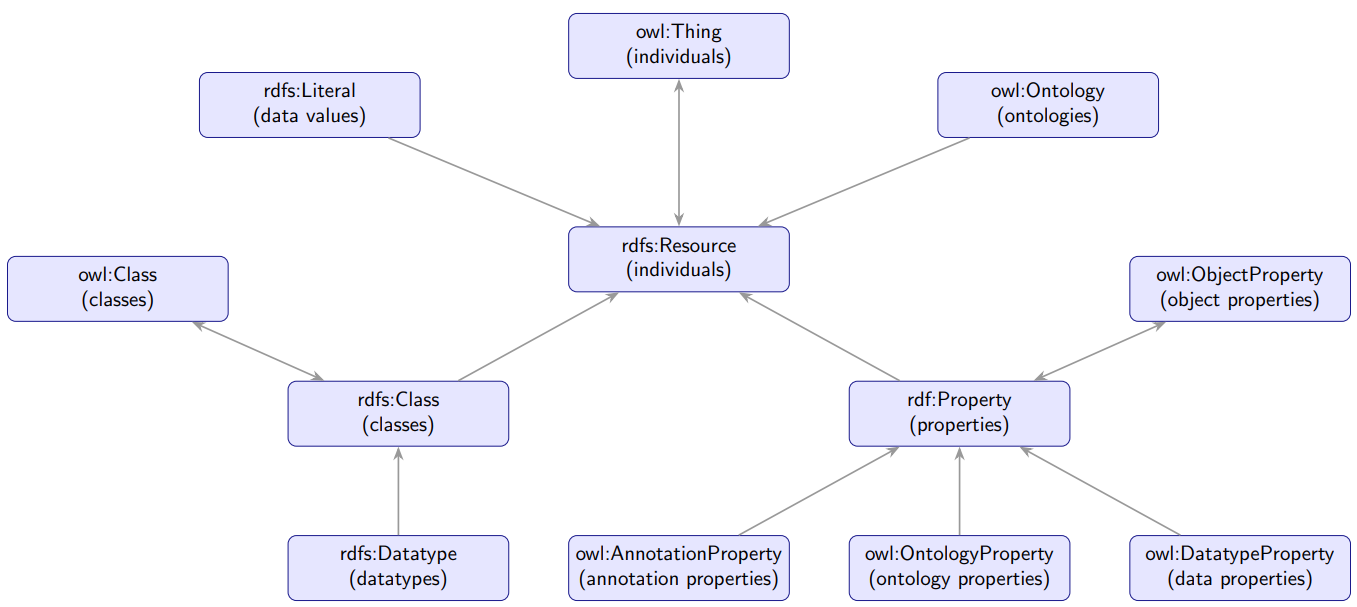

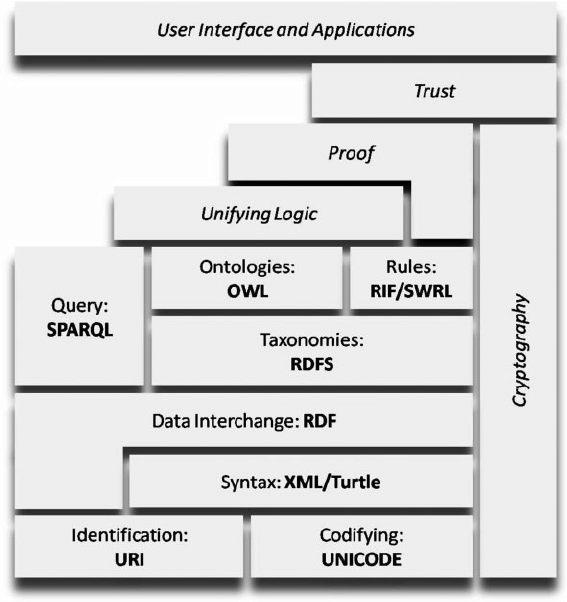

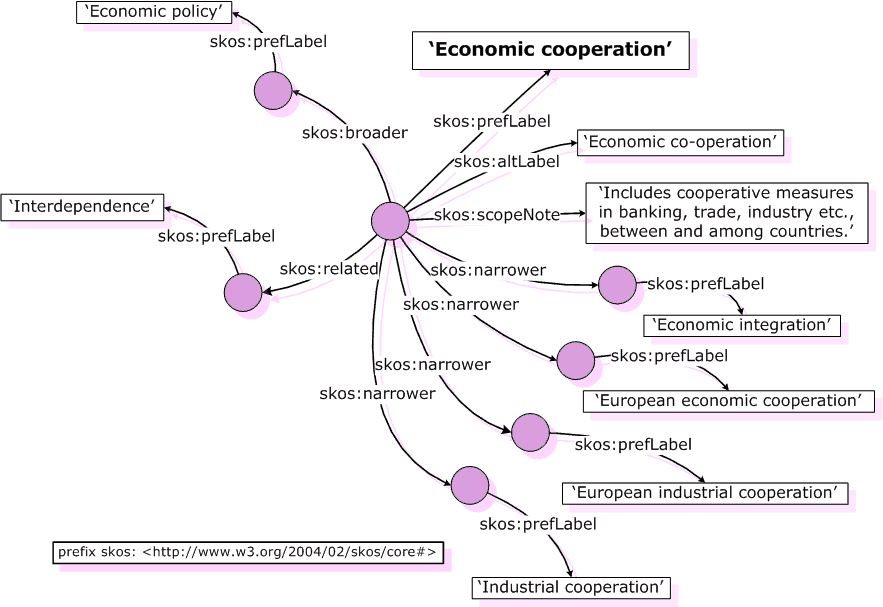

At the heart of this challenge lies the distinction between Data, Content, and Knowledge. Data are raw, context-free facts, consisting of discrete numbers, symbols, and signals that serve as the basic building blocks of information (e.g., a genomic sequence, a sensor reading) [1]. Content refers to the collection of data organized and formatted for human consumption, most often in unstructured or semi-structured forms such as documents, reports, images, and videos. It is the vessel in which data and information are stored and communicated [6]. Knowledge, in contrast, is a higher-level abstraction. It is information that has been processed, contextualized, and synthesized, enabling inferences, judgments, and informed decisions. It represents an understanding of the relationships between information and its applicability to a specific domain [7]. Crucially, the management and transformation of these assets, from data, through content, to knowledge, has historically been an almost entirely manual process, relying on the intensive labor of human experts. The central problem addressed by this paper is that while our ability to generate Data and encapsulate it in Content has grown exponentially, our systems for transforming that content into verifiable, reusable, and machine-readable, actionable Knowledge have not kept pace. Therefore, this framework is designed to bridge that gap by providing a roadmap for automation, transforming the manual task of knowledge discovery into an intelligent, machine-assisted process.

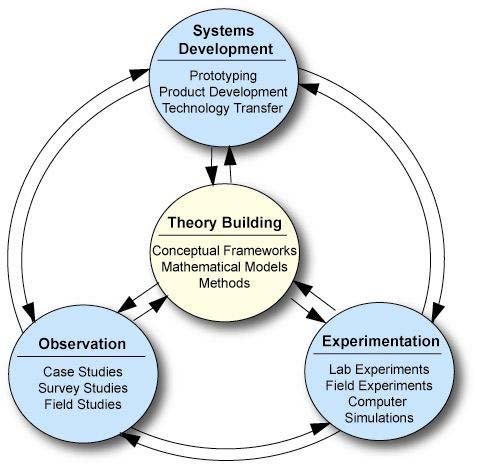

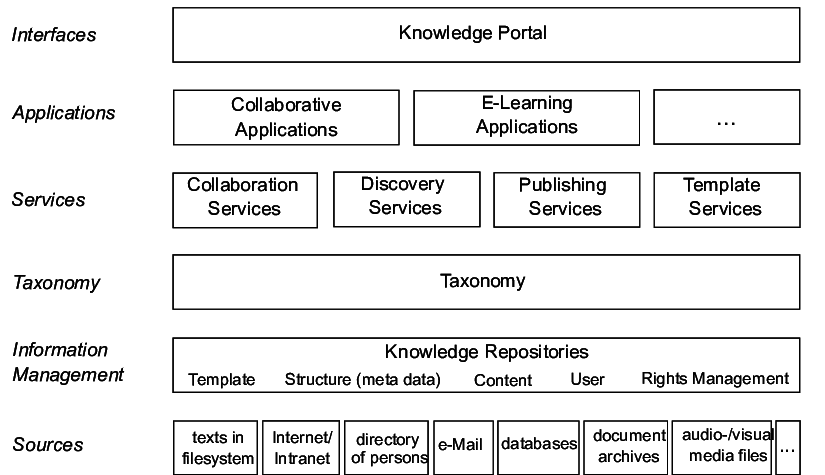

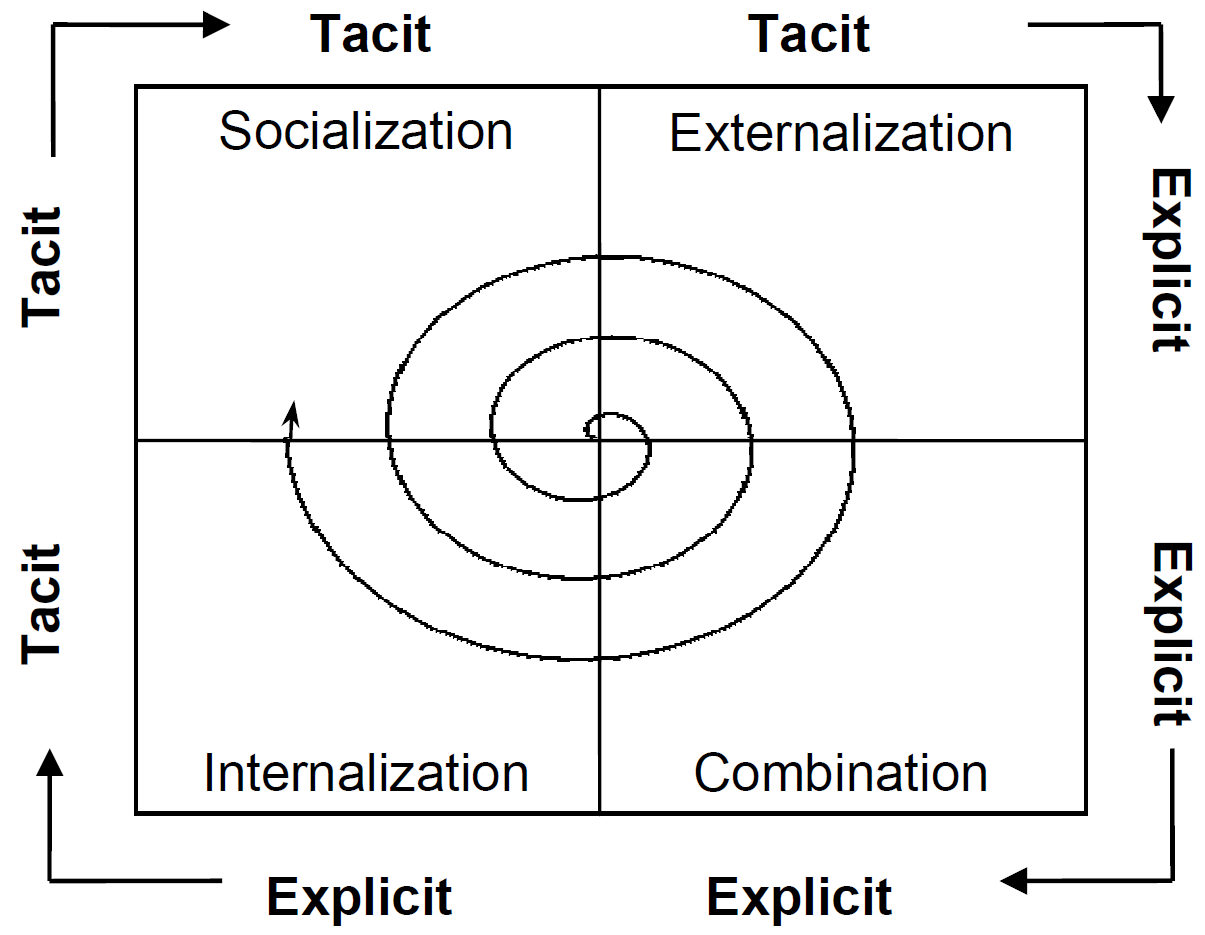

To address these issues, foundational concepts from both Content Management Systems (CMS) and Knowledge Management Systems (KMS) have long been established. While a CMS provides the technological backbone for managing digital content, which includes documents, media, and other vessels of information, a KMS aims for a higher goal: the systematic management of an organization’s intellectual capital [7]. The evolution of KMS can be traced through distinct generations. The first was largely technology-centric, often taking the form of sophisticated CMS platforms focused on the codification and storage of explicit knowledge. The second generation recognized the limitations of this approach and shifted focus to people, emphasizing the importance of tacit knowledge and the social networks constituting “communities of practice” [8]. The current era, however, necessitates a third generation of KMS. This next wave must intelligently synthesize the strengths of the previous two, creating a sophisticated socio-technical system where humans and Artificial Intelligence (AI) collaborate in a virtuous cycle [9]. The system itself must evolve from a passive repository

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.