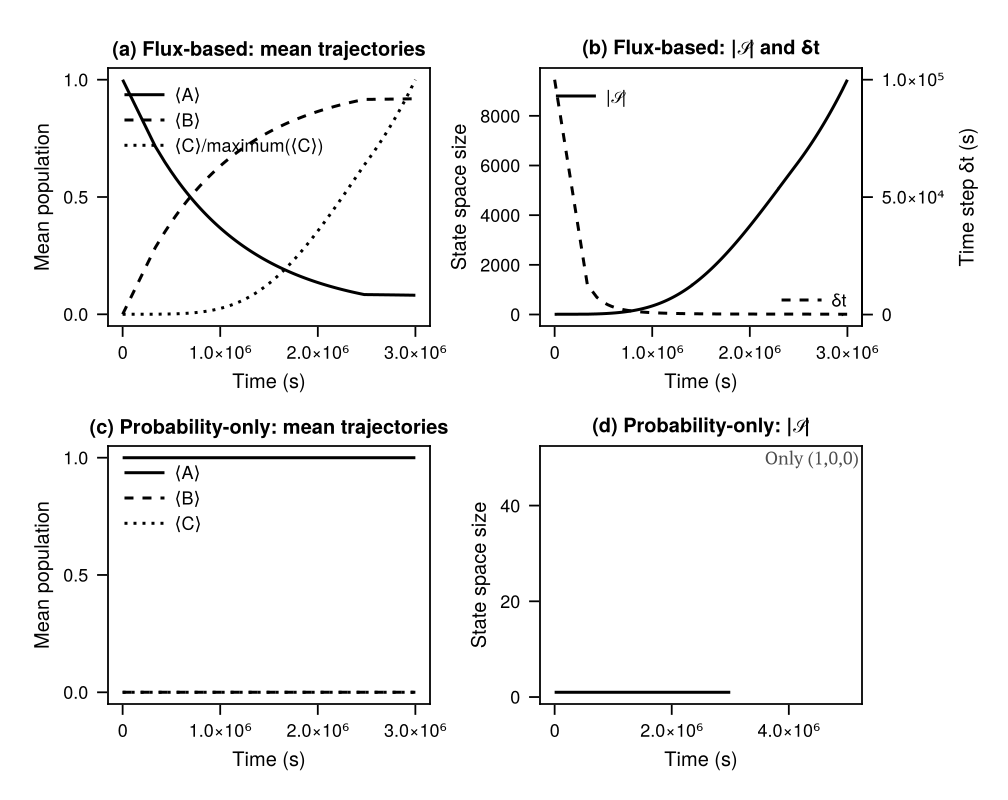

The Finite State Projection (FSP) method approximates the Chemical Master Equation (CME) by restricting the dynamics to a finite subset of the (typically infinite) state space, enabling direct numerical solution with computable error bounds. Adaptive variants update this subset in time, but multiscale systems with widely separated reaction rates remain challenging, as low-probability bottleneck states can carry essential probability flux and the dynamics alternate between fast transients and slowly evolving stiff regimes. We propose a flux-based adaptive FSP method that uses probability flux to drive both state-space pruning and time-step selection. The pruning rule protects low-probability states with large outgoing flux, preserving connectivity in bottleneck systems, while the time-step rule adapts to the instantaneous total flux to handle rate constants spanning several orders of magnitude. Numerical experiments on stiff, oscillatory, and bottleneck reaction networks show that the method maintains accuracy while using substantially smaller state spaces.

1. Introduction. The Chemical Master Equation (CME) governs the evolution of probability distributions for well-mixed stochastic reaction networks and is the canonical description of intrinsic noise in biochemical systems [13,33]. Formally, the CME is an infinite system of linear ODEs posed on a countably infinite lattice of molecular population states. Because the reachable state space typically grows combinatorially with copy numbers, the CME cannot be solved directly without an adaptive or carefully structured truncation scheme.

An important observation for practical biochemical systems is that their probability distributions are naturally sparse: most of the theoretically infinite state space carries negligible probability. The Finite State Projection (FSP) method [21] exploits this sparsity by restricting the CME to a finite subset of states that carry most of the probability mass, yielding a finite-dimensional system that can be solved exactly together with a priori bounds on the truncation error. Several optimizations and variants have since been developed [16,32,9,30,15,2]. We briefly review some of these variants in section 1.1 and direct the reader to [8] for a detailed literature review.

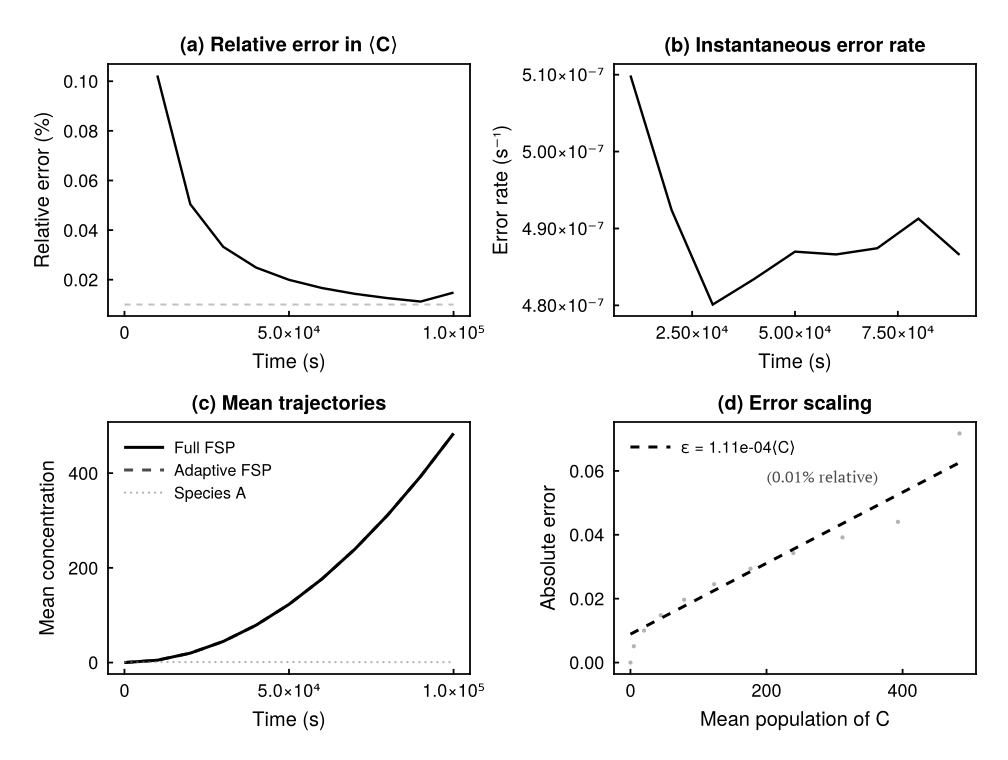

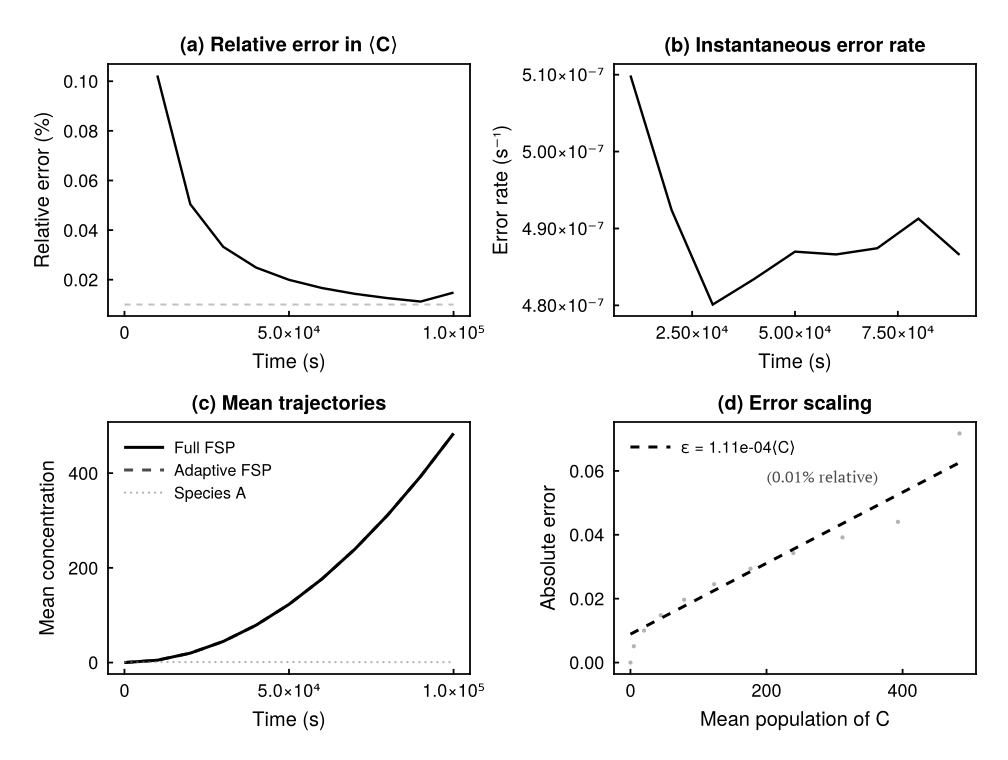

In this paper we focus on stiff biochemical reaction networks [14,4,33], where reaction rates span many orders of magnitude and the dynamics must be tracked over long time horizons. Stiff stochastic systems create several numerical complications and require adaptive methods that adjust simulation parameters locally in time to match the instantaneous demands of the dynamics. We introduce a flux-based adaptive FSP method that addresses both spatial and temporal stiffness. The central idea is to use a quantitative measure of boundary activity, given by the rate at which the probability distribution flows, to adaptively control both state space truncation and time stepping and to obtain computable error bounds without stationary information. This allows the method to retain states with very low probability that are nevertheless essential for preserving connectivity of the underlying Markov process. The time step selection uses the system flux as an activity indicator and automatically adjusts step sizes across multiple time scales.

1.1. Related Work. We review prior work on adaptive FSP methods and state space truncation strategies for stochastic chemical kinetics. The original FSP method [21] introduced fixed truncation with rigorous error bounds based on the probability flux leaving the truncated domain. Munsky and Khammash [22] extended this framework to time-stepping variants that repeatedly expand the state space along reachable directions, providing adaptive control of the truncation error over time.

Peles et al. [24] combined FSP with time scale separation techniques, using eigenvalue-based decompositions to separate slow and fast subsystems and aggregating rarely visited states into sink states with a priori error bounds. Related aggregation techniques for stiff Markov chains were developed by Bobbio and Trivedi [1], who compute cumulative measures efficiently by lumping rapidly evolving subsets of states. This approach achieves substantial model reduction but requires identifying and separating fast and slow dynamics a priori, which is difficult when time scales are not well separated. Zhang, Watson, and Cao [35] introduced an adaptive aggregation method for the CME that groups micro-states into macro-states using information gathered from Monte Carlo simulation, thereby reducing the effective dimensionality of the system despite the lack of explicit a priori error estimates.

MacNamara et al. [19] developed hybrid FSP-leap (FSP-tau-leaping) schemes using Krylov subspace methods, showing that CME-based solvers can efficiently detect equilibrium, compute moments, and generate approximate sample paths for bistable systems such as the genetic toggle switch. Kuntz et al. [18] introduced the exit-time finite state projection (ETFSP) approach, a truncation-based extension of FSP that yields lower bounds on exit distributions and occupation measures, together with computable total-variation error bounds that decrease monotonically and converge as the truncation is enlarged. For reaction networks with conserved quantities, the slack reactant method [17] exploits stoichiometric constraints to reduce the effective dimensionality of the state space, pruning states that violate conservation laws.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the CME and FSP framework. Section 3 presents the flux-based pruning rule, adaptive time step selection, and CME matrix construction algorithm. Section 4 derives local and global error bounds. Section 5 reports numerical experiments on four benchmark systems, including rigorous error analysis for a bottleneck reaction network and computational efficiency evaluation of the matrix reconstruction approach. Section 6 discusses the results and Section 7 concludes

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.