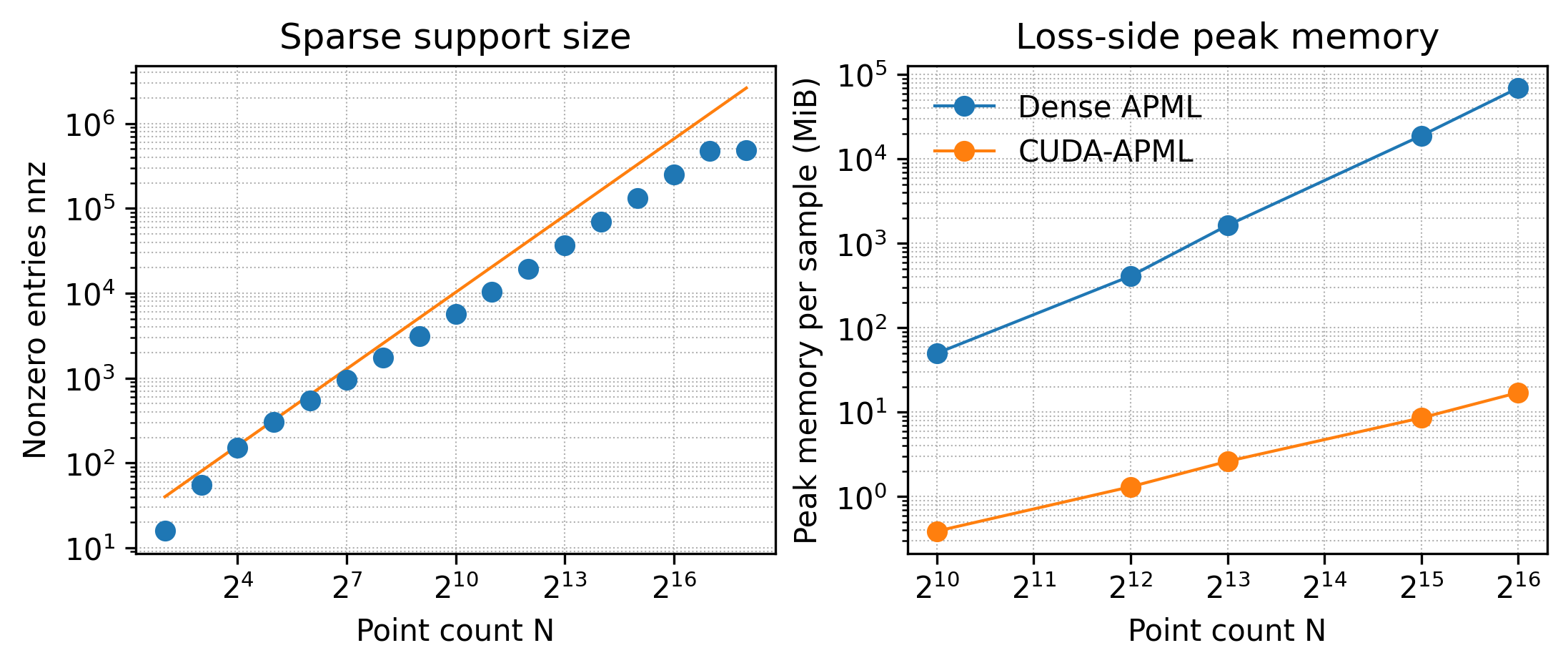

Loss functions are fundamental to learning accurate 3D point cloud models, yet common choices trade geometric fidelity for computational cost. Chamfer Distance is efficient but permits many-to-one correspondences, while Earth Mover Distance better reflects one-to-one transport at high computational cost. APML approximates transport with differentiable Sinkhorn iterations and an analytically derived temperature, but its dense formulation scales quadratically in memory. We present CUDA-APML, a sparse GPU implementation that thresholds negligible assignments and runs adaptive softmax, bidirectional symmetrization, and Sinkhorn normalization directly in COO form. This yields near-linear memory scaling and preserves gradients on the stored support, while pairwise distance evaluation remains quadratic in the current implementation. On ShapeNet and MM-Fi, CUDA-APML matches dense APML within a small tolerance while reducing peak GPU memory by 99.9%. Code available at: https://github.com/Multimodal-Sensing-Lab/apml

Three-dimensional point clouds represent geometry from LiDAR, depth cameras, and structured-light scanners, and they also appear in cross-modal pipelines that infer 3D structure from non-visual measurements. Point cloud learning supports robotics, AR and VR, wireless human sensing, and digital twin pipelines [1]- [4]. In supervised settings, models output unordered point sets, so training requires permutation-invariant losses that remain stable at large point counts.

Matching quality and scalability are often in tension. Nearest-neighbor objectives are efficient but allow many-toone assignments that can degrade geometric coverage, whereas optimal transport losses better reflect one-to-one matching but are costly at training scale. This cost constrains batch size and point count, reduces the number of feasible training runs under fixed compute budgets, and increases energy and monetary cost during GPU training and tuning. APML [5] narrows this gap by constructing a differentiable transport plan with temperature-scaled similarities and Sinkhorn normalization, using an analytically derived temperature. However, its dense formulation stores pairwise matrices with quadratic memory growth, which can dominate training resources. For example, [5] reported close to 300 GB of GPU memory when training This research was supported by the Research Council of Finland 6G Flagship Programme (Grant 346208), Horizon Europe CONVERGE (Grant 101094831), and Business Finland WISECOM (Grant 3630/31/2024).

- These authors contributed equally to this work.

FoldingNet [6] on ShapeNet-55 [7]. Such requirements restrict use in higher-resolution regimes that arise in large scenes and repeated updates, including mapping and digital twin pipelines [8]- [13].

We present CUDA-APML, a sparse GPU implementation of APML that exploits the empirical sparsity of the transport plan after adaptive softmax thresholding. CUDA-APML constructs bidirectional assignments directly in COO form, performs ondevice symmetrization and Sinkhorn normalization on the sparse support, and computes the loss and gradients without materializing dense matrices. On ShapeNet and MM-Fi, CUDA-APML matches dense APML within a small tolerance while reducing peak GPU memory by up to 99.9%, improving the practical cost profile of transport-based supervision for point cloud and cross-modal 3D learning.

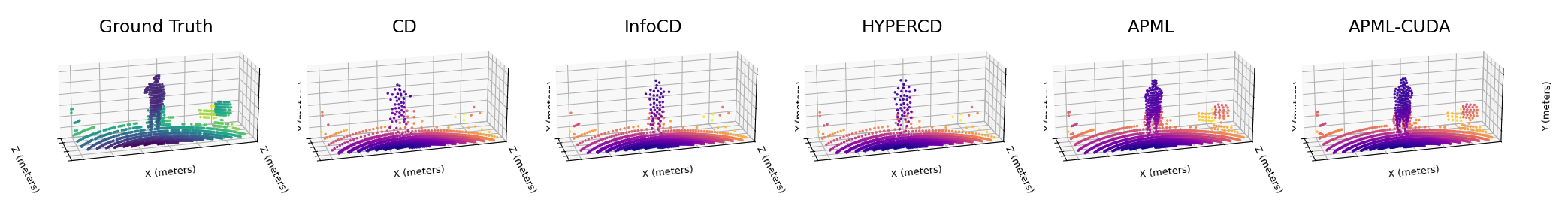

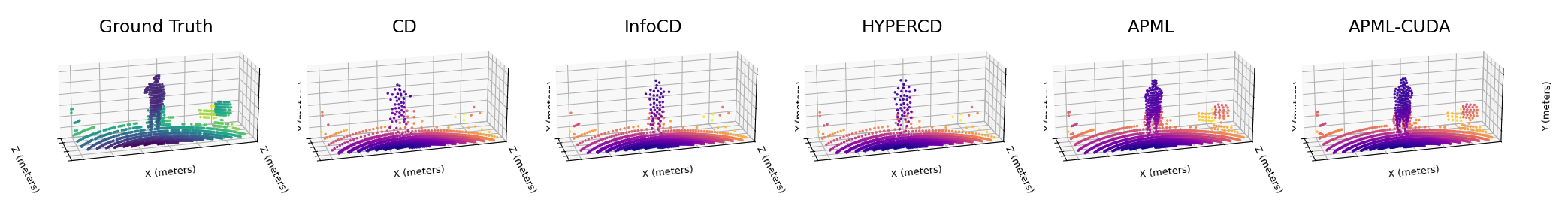

Point cloud learning requires permutation-invariant losses that compare unordered predicted point sets with reference point sets. Chamfer Distance (CD) is widely used because it reduces the comparison to nearest-neighbor distances computed in both directions [2], [14]. However, its many-to-one assignments can cause point clustering in dense regions and weak coverage in sparse regions [15]. Extensions such as density-aware CD (DCD) [16], HyperCD [15], and InfoCD [17] mitigate some of these effects but still rely on nearestneighbor matching and remain sensitive to sampling density and local ambiguities. By contrast, Earth Mover Distance (EMD) enforces one-to-one transport and better reflects structural alignment [18], but its computational cost and common equal-cardinality constraints limit its use in training. Alternatives include projected distances such as sliced Wasserstein and approximate transport solvers [19], [20], which often introduce additional design choices and may not match full transport behavior on heterogeneous point distributions.

Entropy-regularized optimal transport provides a differentiable approximation of EMD that can be computed by Sinkhorn normalization [21], [22]. Sinkhorn-based losses have been used for soft correspondence problems such as registration and feature matching [23], [24], but typically require tuning the regularization strength to balance sharpness and stability. APML [5] builds a temperature-scaled similarity matrix from pairwise distances and applies Sinkhorn normalization to obtain soft correspondences with approximately one-to-one marginals. Its temperature is derived from local distance gaps to enforce a minimum assignment probability, reducing manual tuning, but its dense formulation stores and updates pairwise matrices with quadratic memory growth, which restricts batch size and point count in practice [5].

Scaling optimal transport has been studied through sparse or structured support restriction and low-rank approximations [25]- [27]. In parallel, kernel-level designs show that removing dense intermediates can shift practical limits for quadratic operators, as in FlashAttention [28] and KeOps [29]. In 3D perception, sparse tensor engines and point-based libraries provide GPU support for irregular sparsity patterns to improve memory behavior and throughput [30], [31]. These directions motivate a sparse and GPU-oriented implementation of APML. In this work, we exploit the empirical sparsity of the APML transport plan after adaptive softmax thresholding and run symmetrization and Sinkhorn normalization on the sparse support to re

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.