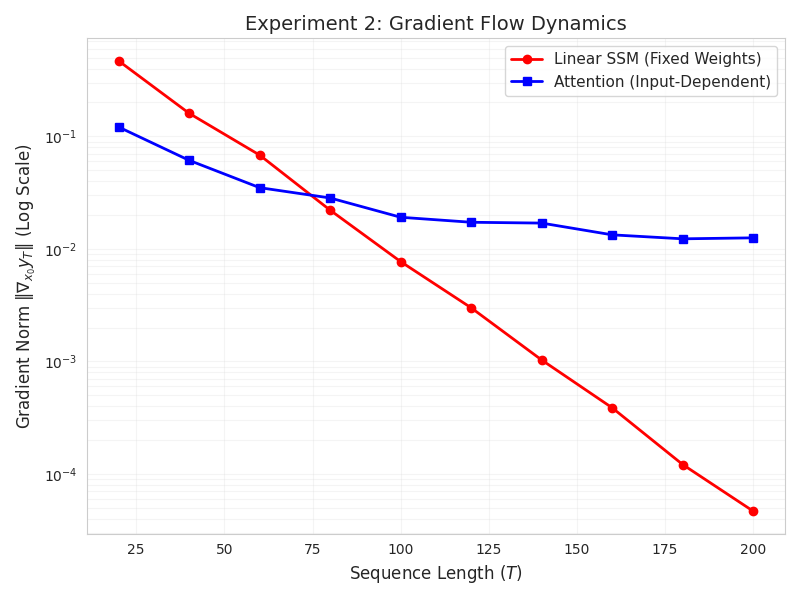

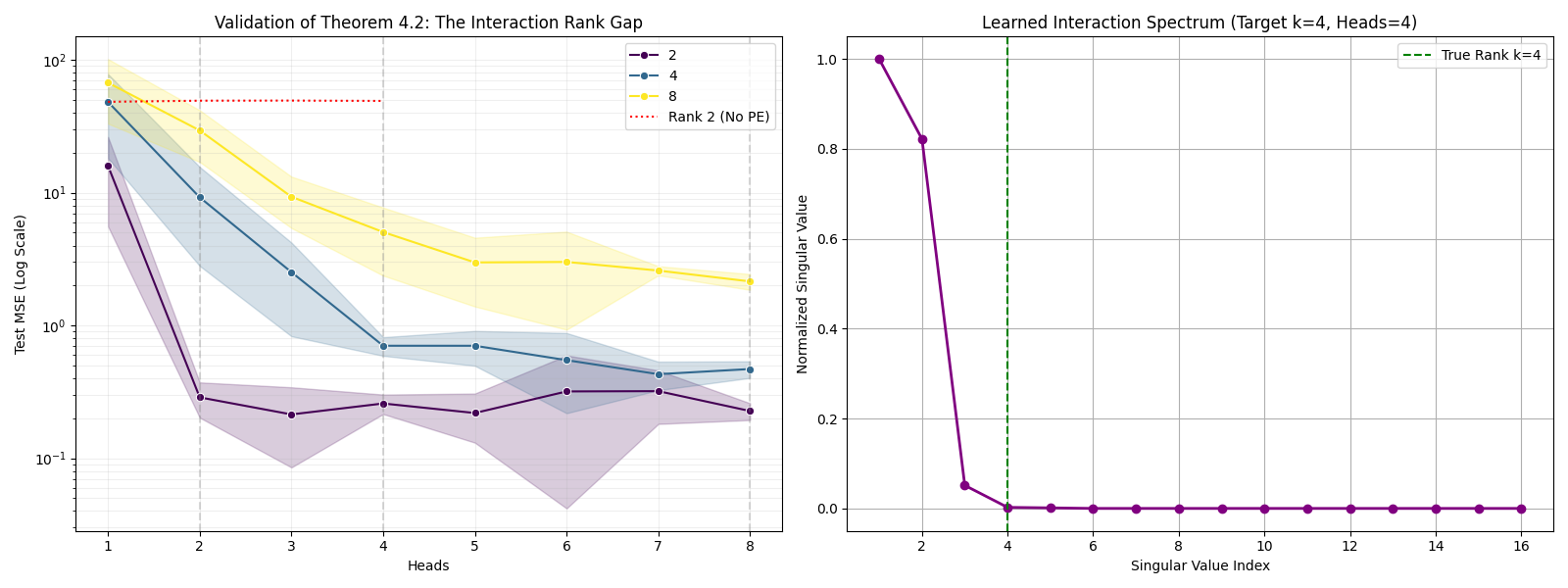

Sequence modeling has produced diverse architectures -- from classical recurrent neural networks to modern Transformers and state space models (SSMs) -- yet a unified theoretical understanding of expressivity and trainability trade-offs remains limited. We introduce a unified framework that represents a broad class of sequence maps via an input-dependent effective interaction operator $W_{ij}(X)$, making explicit two recurring construction patterns: (i) the Unified Factorized Framework (Explicit) (attention-style mixing), in which $W_{ij}(X)$ varies through scalar coefficients applied to shared value maps, and (ii) Structured Dynamics (Implicit) (state-space recurrences), in which $W_{ij}$ is induced by a latent dynamical system. Using this framework, we derive three theoretical results. First, we establish the Interaction Rank Gap: models in the Unified Factorized Framework, such as single-head attention, are constrained to a low-dimensional operator span and cannot represent certain structured dynamical maps. Second, we prove an Equivalence (Head-Count) Theorem showing that, within our multi-head factorized class, representing a linear SSM whose lag operators span a $k$-dimensional subspace on length-$n$ sequences requires and is achievable with $H=k$ heads. Third, we prove a Gradient Highway Result, showing that attention layers admit inputs with distance-independent gradient paths, whereas stable linear dynamics exhibit distance-dependent gradient attenuation. Together, these results formalize a fundamental trade-off between algebraic expressivity (interaction/operator span) and long-range gradient propagation, providing theoretical grounding for modern sequence architecture design.

1 Introduction: The Landscape of Explicit and Implicit Sequence Models

The field of sequence modeling has arguably bifurcated into two dominant paradigms. On one hand, modern architectures like the Transformer [14] and its variants rely on explicit token-to-token interactions. On the other hand, classical and recent models like Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) [4] and State Space Models (SSMs) [5,7] represent an implicit paradigm through recurrent dynamics and hidden states. Despite their empirical success, these architectures are often studied in isolation, with distinct theoretical vocabularies-geometry and kernels for Attention, versus control theory and differential equations for SSMs. This separation obscures fundamental questions: Are “multi-head” attention mechanisms merely an ensemble most notably the “Transformers are RNNs” perspective [9], which links linear attention to recurrent computations. However, many existing unifications focus on expressing one model class as an efficient approximation of another. In contrast, our work provides a common representational framework that encompasses attention mechanisms and linear state-space models (and, in additional sections, convolutional and feed-forward constructions), enabling rigorous separation and equivalence results (Theorems 4.2 and 4.4) about the expressivity of scalar-factorized interactions versus structured dynamical interactions.

We define a sequence model as a transformation mapping an input sequence X = [x 1 , . . . , x n ] ∈ R d×n to an output sequence Y = [y 1 , . . . , y n ] ∈ R p×n . While traditional feedforward networks employ fixed weights (e.g., Y = V X), modern sequence models require weights that adapt to the context. We propose that all such models can be unified under a single formulation where the transformation is governed by an input-dependent weight tensor W(X) ∈ R n×n×p×d . The output token y i is computed as a weighted sum of all input tokens x j , mediated by the subtensor W ij ∈ R p×d which represents the specific linear map between position j and position i:

The tensor W ij captures the effective weight matrix applied to token x j to produce its contribution to y i . Direct instantiation of this 4D tensor requires O(n 2 pd) parameters, which is computationally intractable. Consequently, all practical architectures can be viewed as distinct strategies for factorizing or implicitly defining W ij .

The most common strategy is to constrain the interaction matrix W ij to be a rank-1 factorization of a scalar interaction score w ij and a shared value matrix V ∈ R p×d . This dramatically reduces the parameter count from O(n 2 pd) to O(n 2 + pd). Definition 3.1 (Unified Factorized Model). A model belongs to the Unified Factorized class if its weight tensor decomposes as

where V ∈ R p×d is a shared value matrix and f θ : R d × R d → R is a scalar token-pair weight function. The output equation becomes

In matrix notation, defining the scalar weight matrix A(X) ∈ R n×n with entries A ij = f θ (x i , x j ), the operation factorizes as

This highlights that the output is a linear combination of the transformed inputs V X. In general, x i may be understood to include any fixed positional features; thus f θ can represent purely positional weights (e.g., δ ij or c i-j ) as well as content-dependent weights.

Within this class, we distinguish between static factorization, where f θ depends only on positional indices, and dynamic factorization, where f θ depends on the content of X.

In these models, the interaction strength w ij is determined solely by the relative or absolute positions of tokens i and j, independent of the token content.

• MLP (Feedforward): The Multi-Layer Perceptron treats tokens independently. The interaction function is the Kronecker delta f θ (x i , x j ) = δ ij . Substituting this into the unified equation yields y i = j δ ij V x j = V x i , which recovers the standard layer-wise transformation. Matrix Form: Y = V XI = V X. The effective weight interaction matrix is the Identity.

• CNN (Convolution): Local, shift-invariant weights:

Substituting this into Eq. ( 1) gives:

Change variable k = i -j, so j = i -k and |k| ≤ r:

This matches the definition of a 1D discrete convolution of the sequence (V X) with kernel [c -r , . . . , c 0 , . . . , c r ]. Matrix Form: Y = V XC ⊤ Toeplitz , where C Toeplitz is a banded matrix reflecting the local, shift-invariant kernel structure.

These models allow the weight tensor W(X) to adapt to the input sequence, enabling contextaware processing.

• KAN (Kolmogorov-Arnold Network): Based on the Kolmogorov-Arnold representation theorem [1,10], we can approximate a multivariate function using a superposition of univariate functions. For token interactions, we use a separable nonlinear basis expansion with r basis functions:

Each basis pair (g m , h m ) captures a different mode of interaction between tokens. Define the token-pair weight as a sum of separable basis functio

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.