Balancing competing objectives is omnipresent across disciplines, from drug design to autonomous systems. Multi-objective Bayesian optimization is a promising solution for such expensive, black-box problems: it fits probabilistic surrogates and selects new designs via an acquisition function that balances exploration and exploitation. In practice, it requires tailored choices of surrogate and acquisition that rarely transfer to the next problem, is myopic when multi-step planning is often required, and adds refitting overhead, particularly in parallel or time-sensitive loops. We present TAMO, a fully amortized, universal policy for multi-objective black-box optimization. TAMO uses a transformer architecture that operates across varying input and objective dimensions, enabling pretraining on diverse corpora and transfer to new problems without retraining: at test time, the pretrained model proposes the next design with a single forward pass. We pretrain the policy with reinforcement learning to maximize cumulative hypervolume improvement over full trajectories, conditioning on the entire query history to approximate the Pareto frontier. Across synthetic benchmarks and real tasks, TAMO produces fast proposals, reducing proposal time by 50-1000x versus alternatives while matching or improving Pareto quality under tight evaluation budgets. These results show that transformers can perform multi-objective optimization entirely in-context, eliminating per-task surrogate fitting and acquisition engineering, and open a path to foundation-style, plug-and-play optimizers for scientific discovery workflows.

Multi-objective optimization (MOO; Deb et al., 2016;Gunantara, 2018) is ubiquitous in science and engineering: practitioners routinely balance accuracy vs. cost in experimental design (Schoepfer et al., 2024), latency vs. quality in adaptive streaming controllers (Peroni & Gorinsky, 2025), or efficacy vs. toxicity in drug discovery (Fromer & Coley, 2023;Lai et al., 2025). In these settings, each evaluation of the black-box objectives can be slow or costly, making sample efficiency paramount; the goal is to obtain high-quality approximations of the Pareto front with a minimal number of queries.

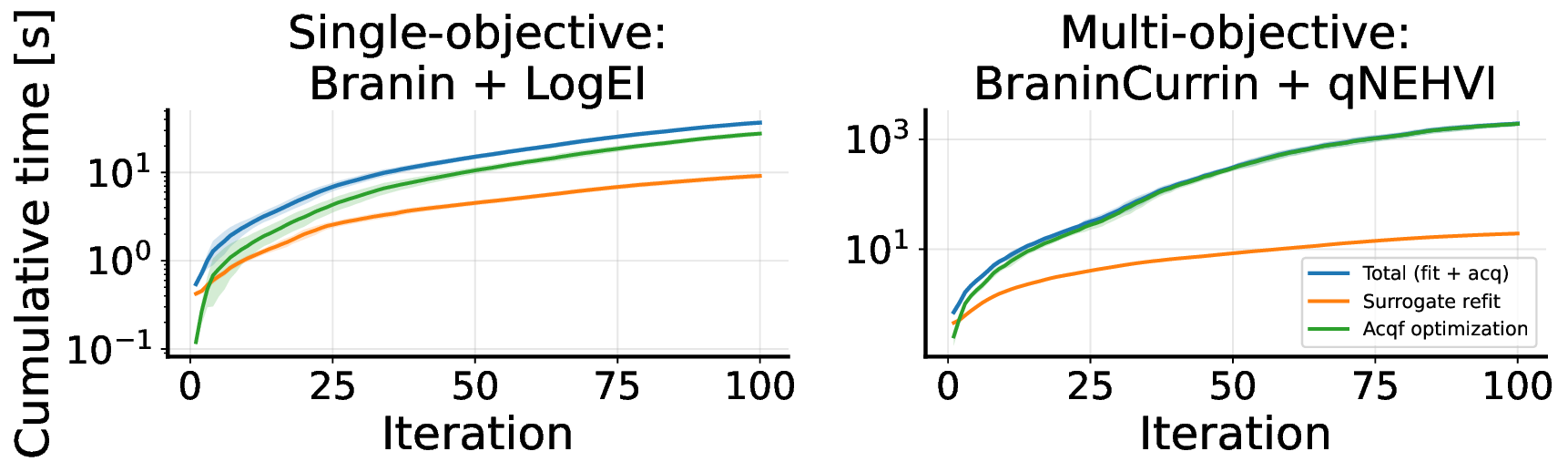

The standard sample-efficient paradigm for such problems is Multi-objective Bayesian optimization (MOBO; Garnett, 2023): fit probabilistic surrogates for each objective, typically using Gaussian processes (GPs; Rasmussen & Williams, 2006), then select the next query by maximizing an acquisition that balances exploration-exploitation to efficiently improve a chosen multi-objective utility, such as hypervolume, scalarizations, or preference-based criteria (Daulton et al., 2020;Belakaria et al., 2019;Daulton et al., 2023b). While effective, this recipe has three drawbacks in real-world use. First, each new problem requires training surrogates from scratch and repeatedly optimizing the acquisition, adding non-trivial GP overhead that can bottleneck decision latency in parallel or time-sensitive settings. Second, performance critically depends on modeling choices (kernel, likelihood, acquisition, initialization), especially when data are scarce, a setting MOBO is intended to handle. Third, most acquisitions are myopic, optimizing a one-step gain, which can be suboptimal when Pareto-front discovery requires multi-step planning.

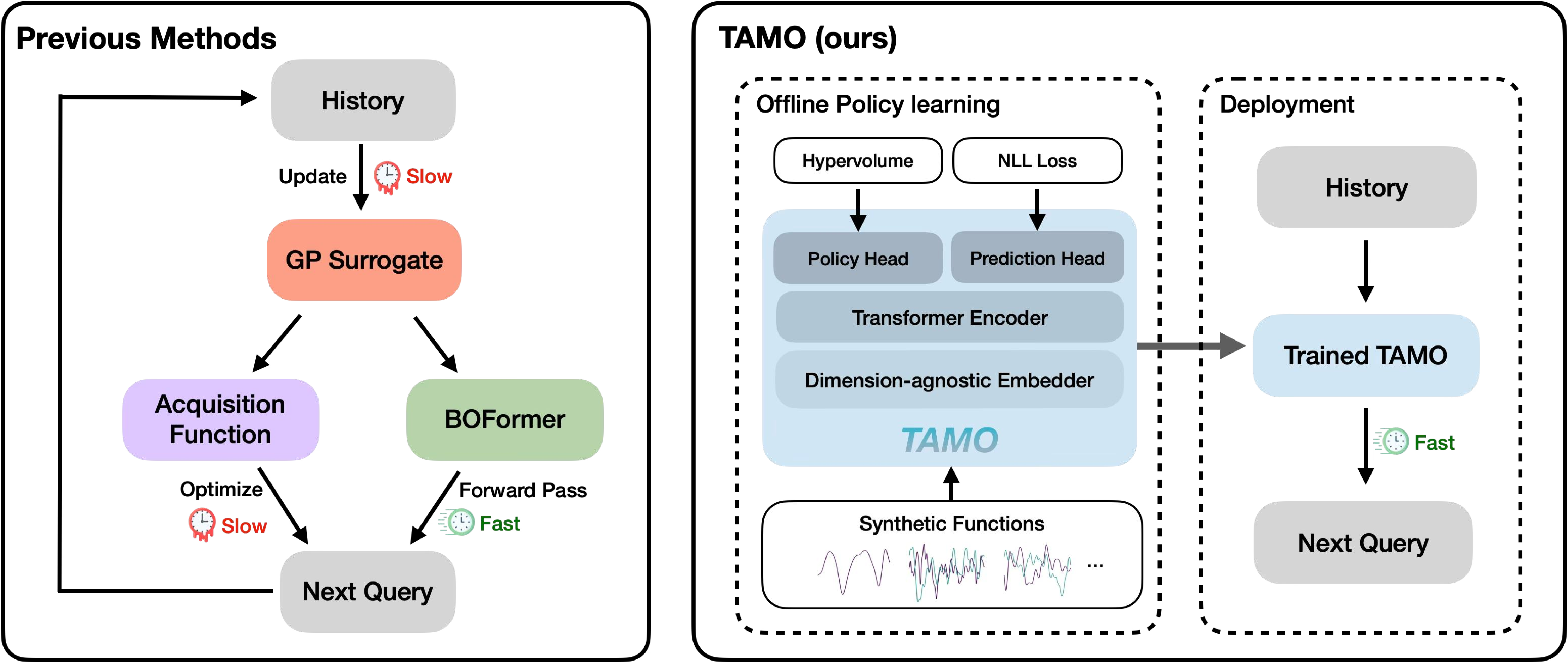

Amortized optimization (Finn et al., 2017;Amos et al., 2023) addresses these issues by shifting computation offline. The idea is to pre-train on a distribution of related optimization tasks, either generated synthetically or drawn from real, previously solved datasets. At test time, proposing a new design then reduces to a single forward pass. Recent efforts have explored methods for amortized Bayesian optimization (Volpp et al., 2020;Chen et al., 2022;Maraval et al., 2023;Zhang et al., 2025;Hung et al., 2025), but few address the multi-objective setting. For instance, Hung et al. ( 2025) only amortizes the acquisition function calculation while still relying on a GP surrogate, and its pretrained model is tied to a fixed number of objectives, which prevents transfer across heterogeneous tasks. A method that tackles these challenges would let practitioners pool heterogeneous legacy datasets for pretraining, resulting in improved outcomes in scarce-data regimes. It would also enable reusing a single optimizer as design spaces and objective counts change, and issue instant proposals in closed-loop laboratories, high-throughput campaigns, reducing overhead when evaluations are cheap or parallel.

Contributions.

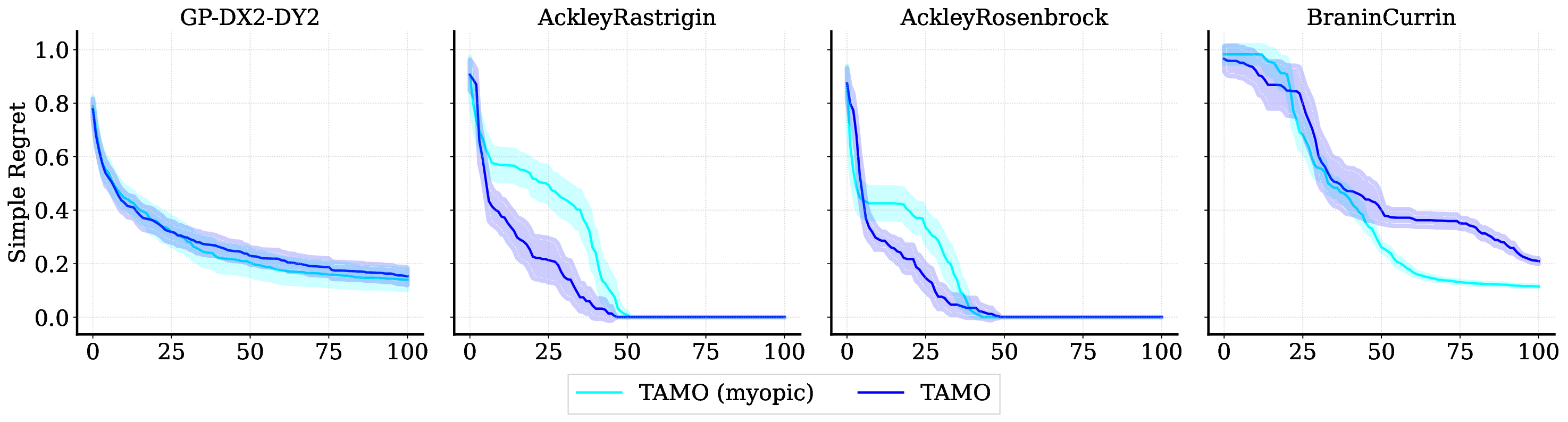

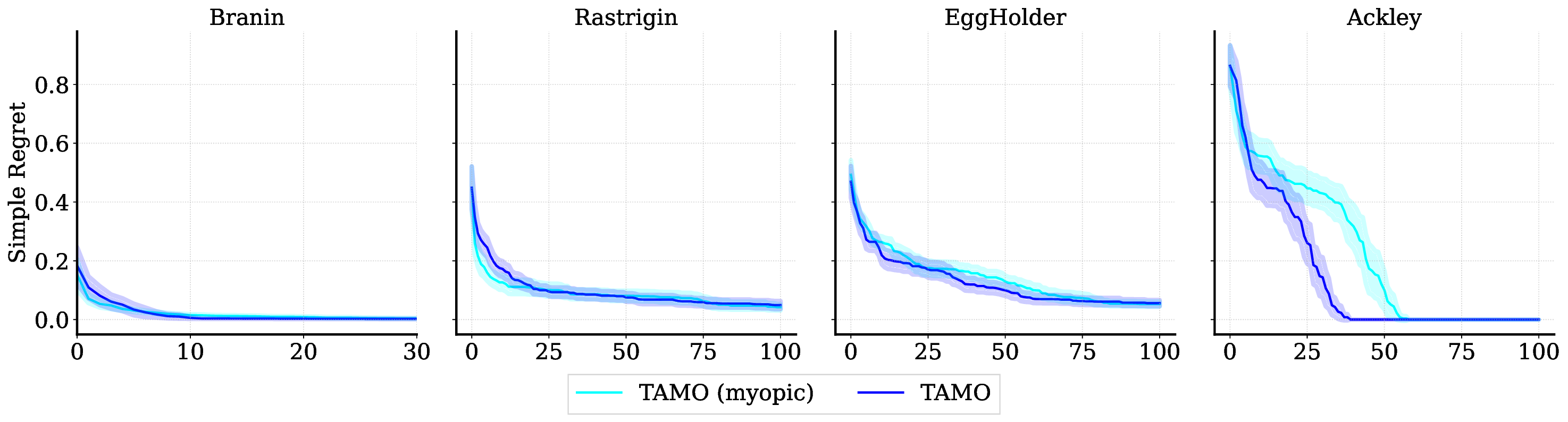

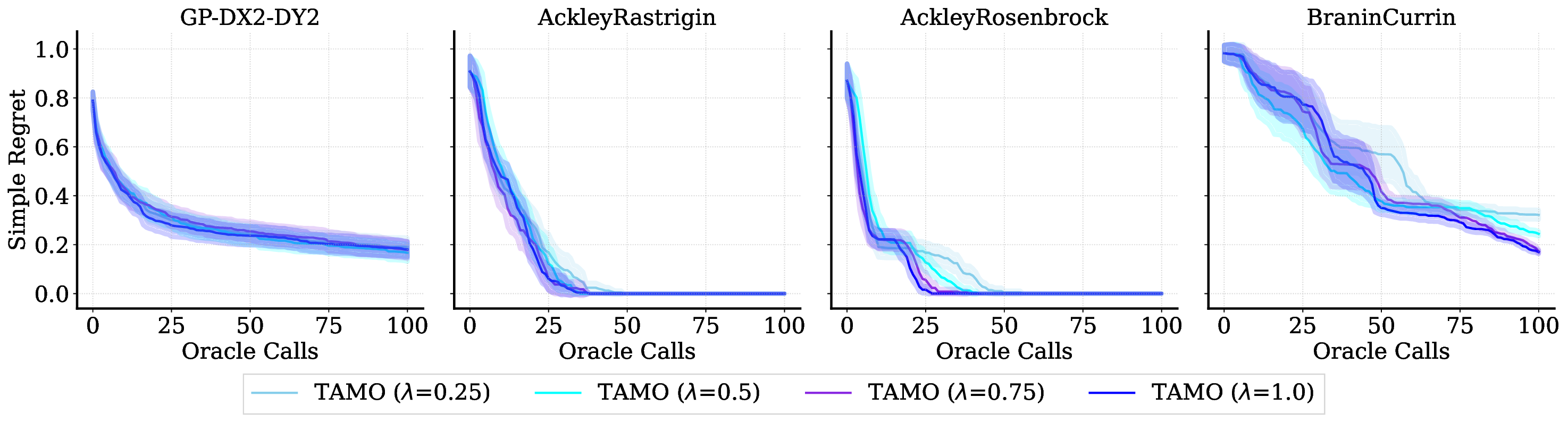

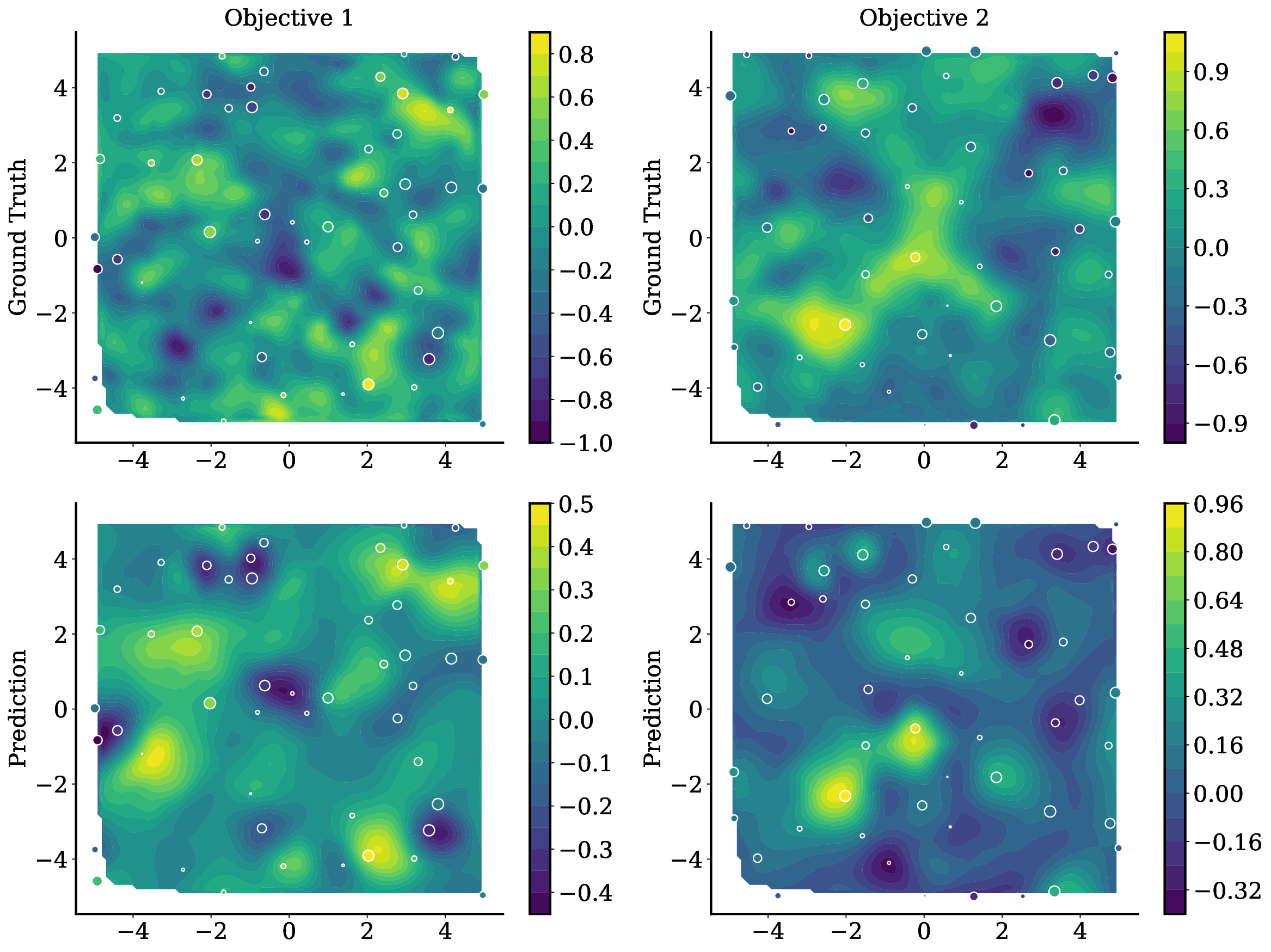

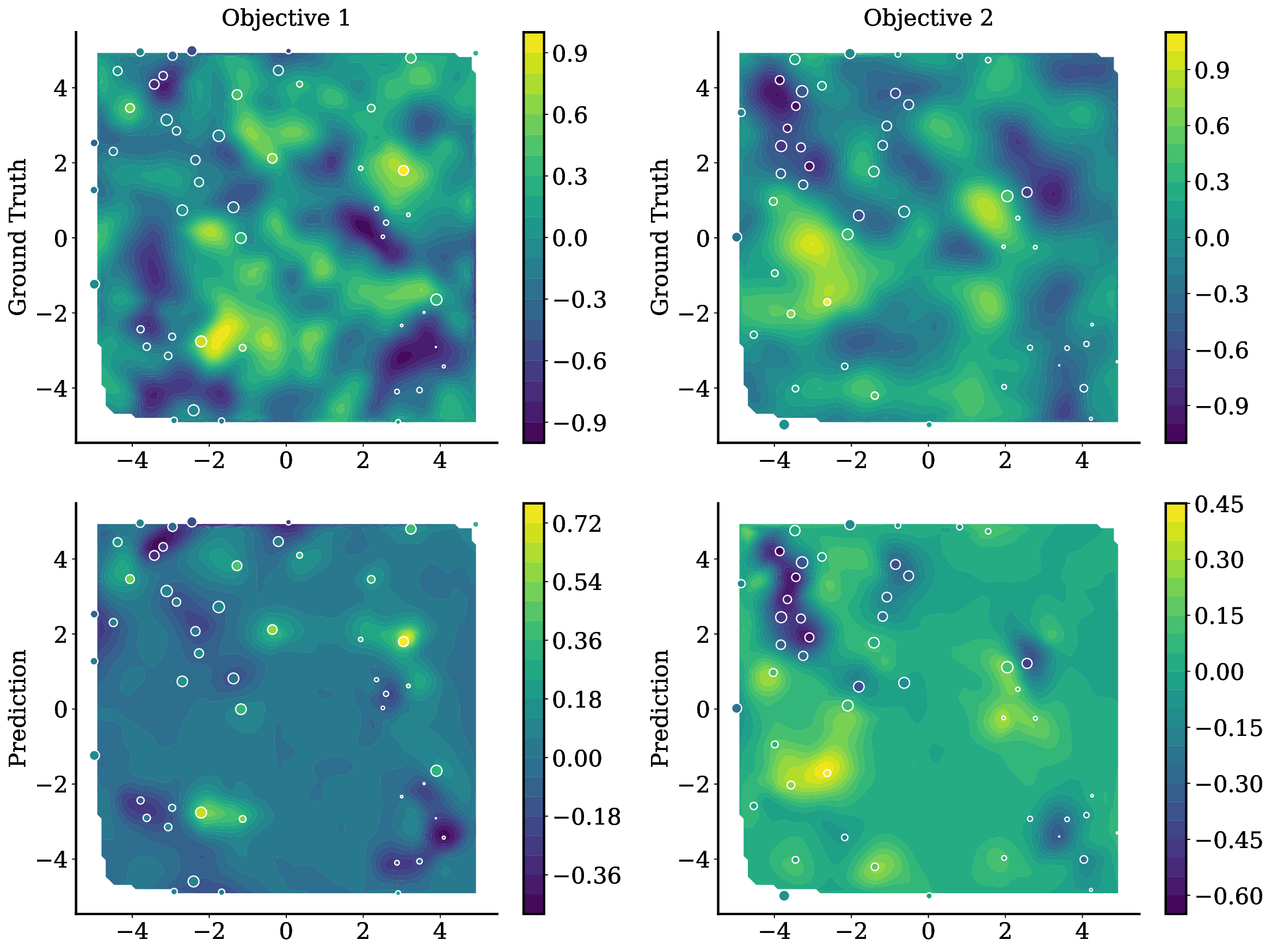

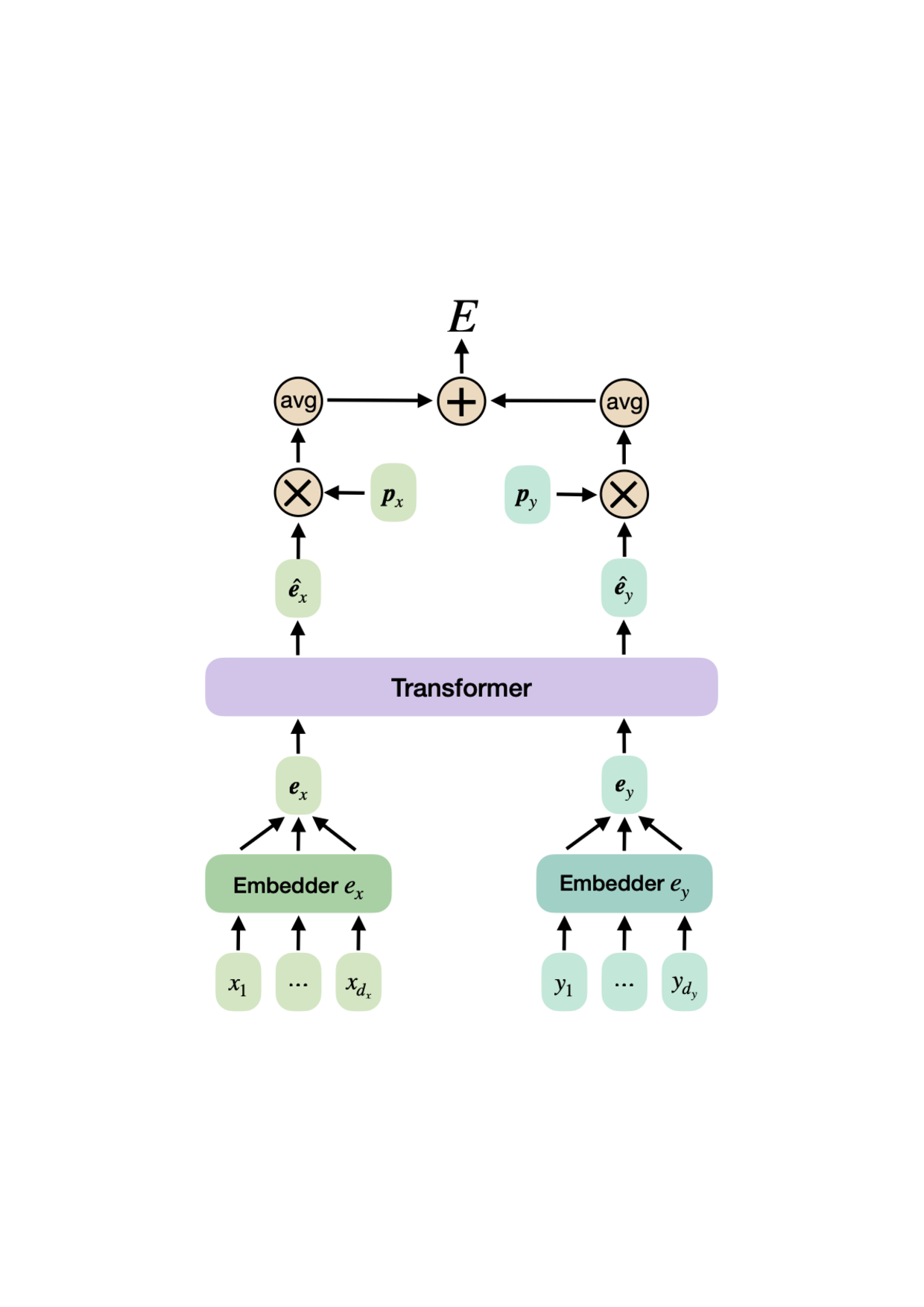

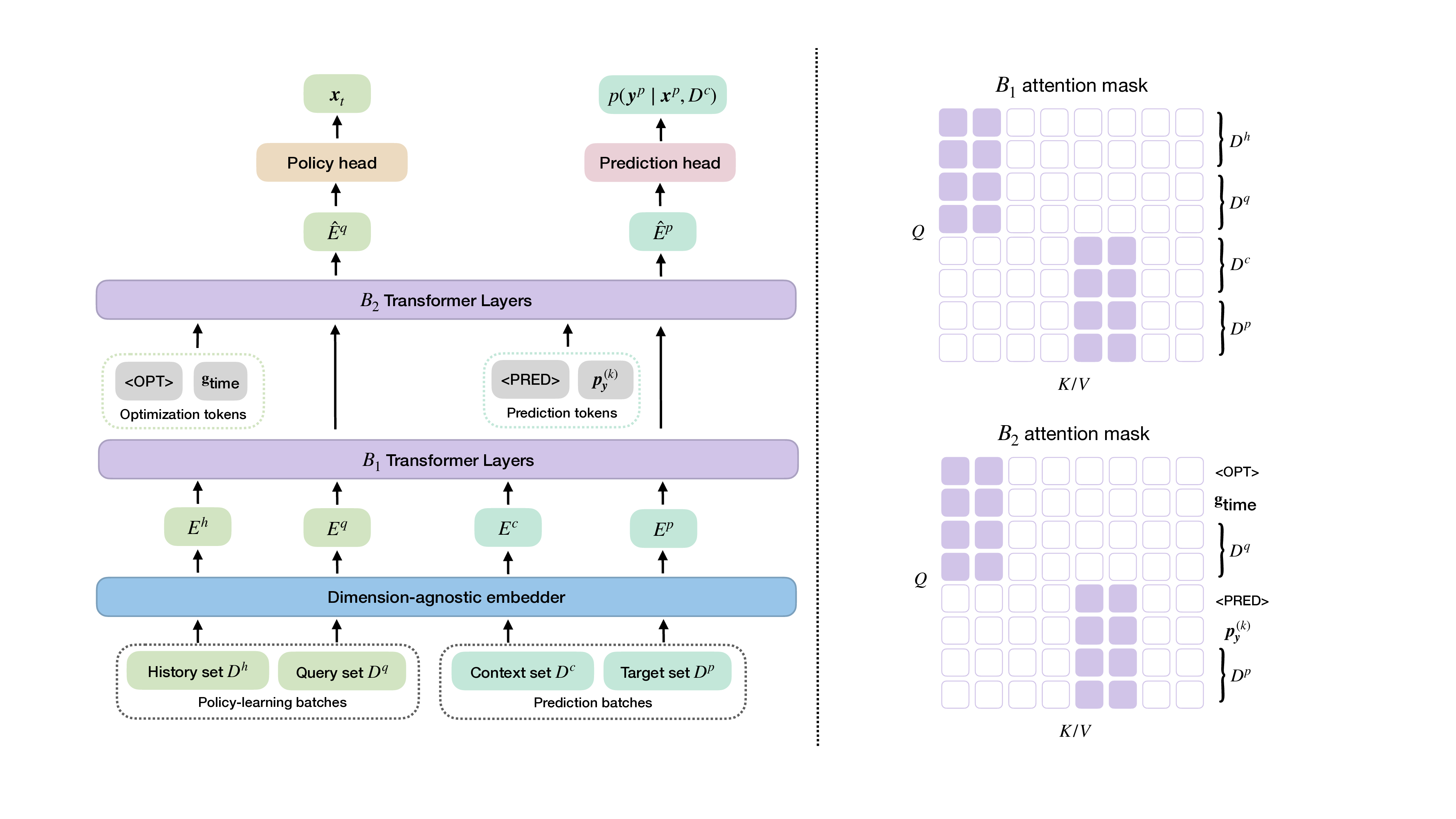

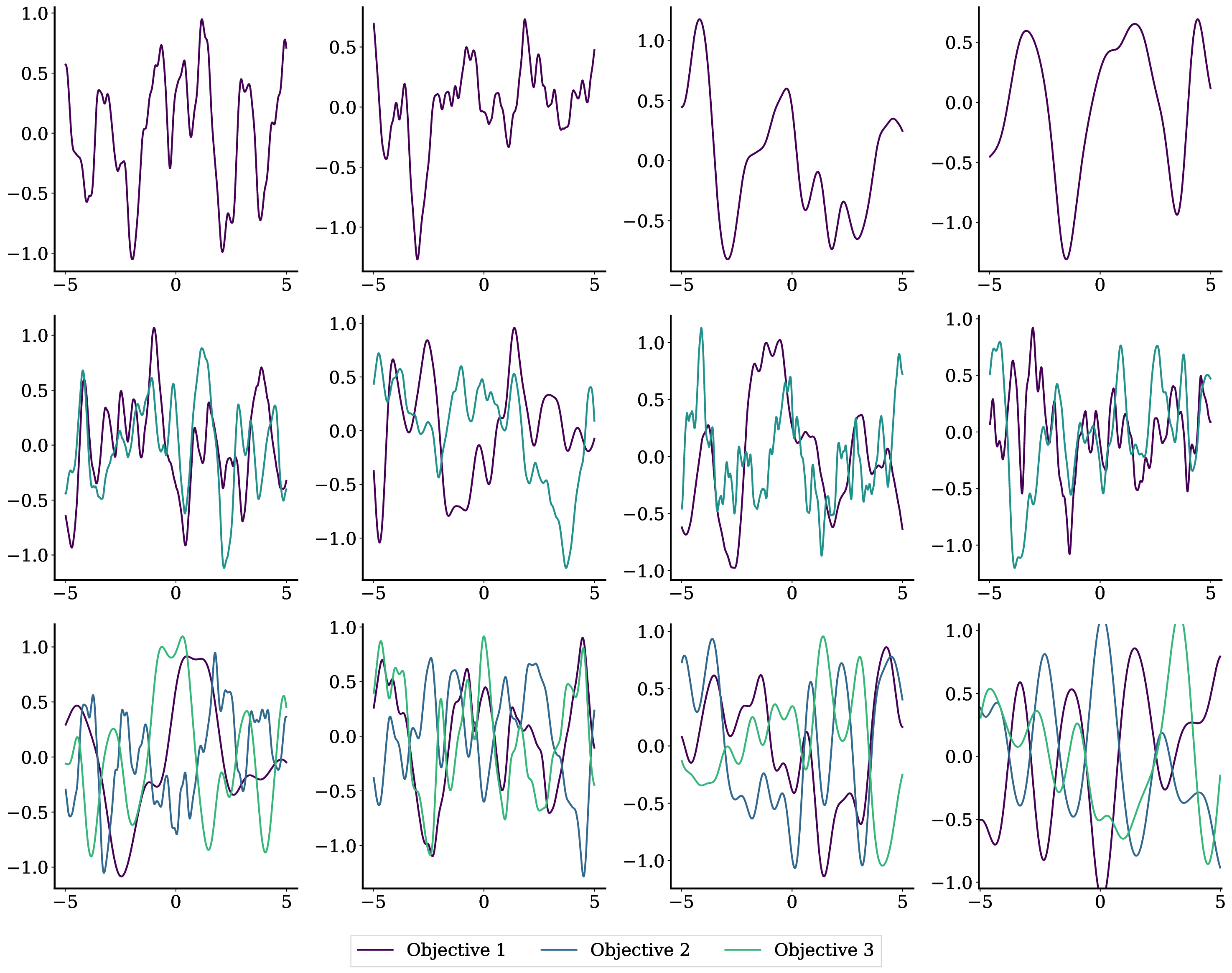

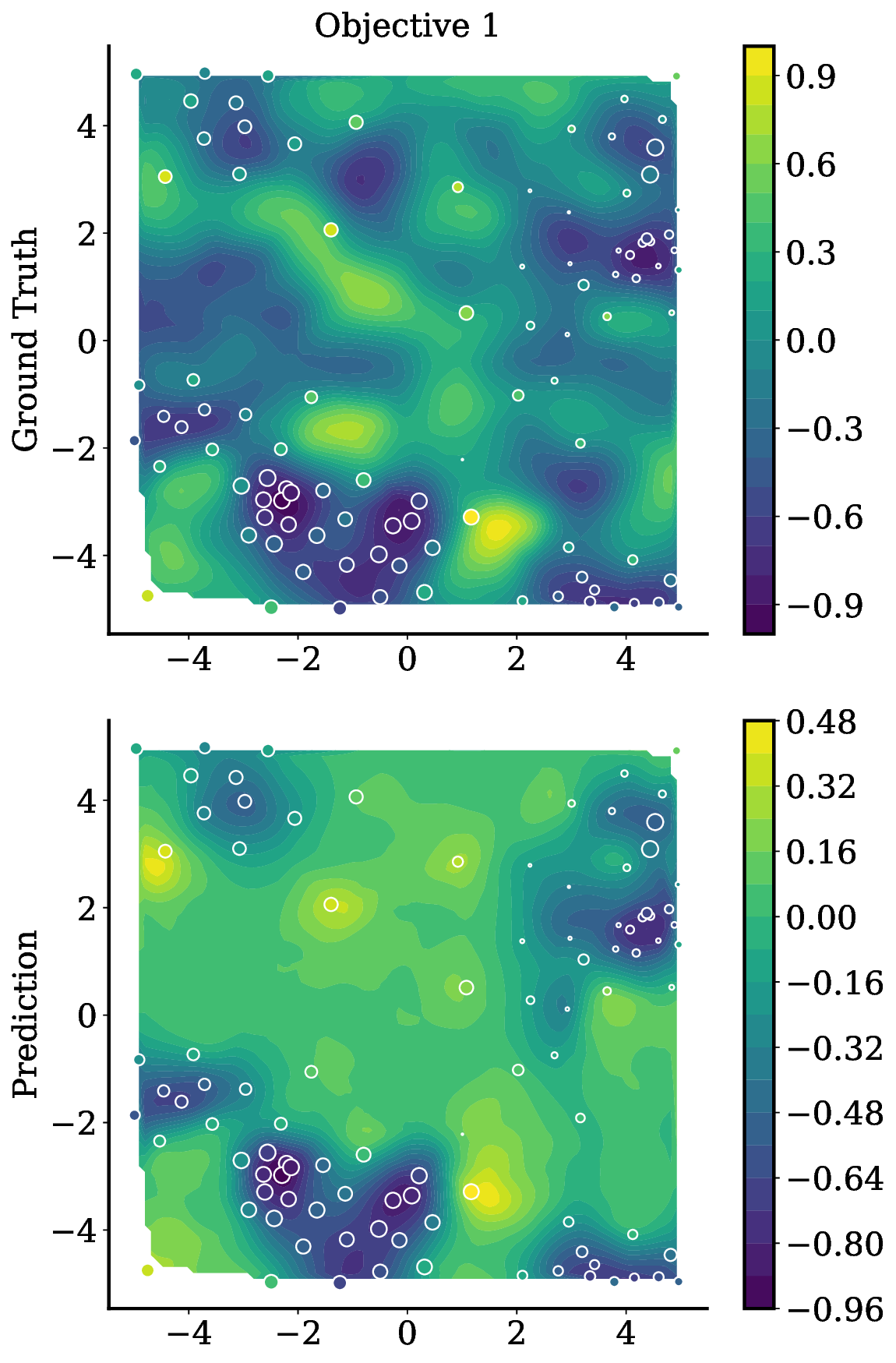

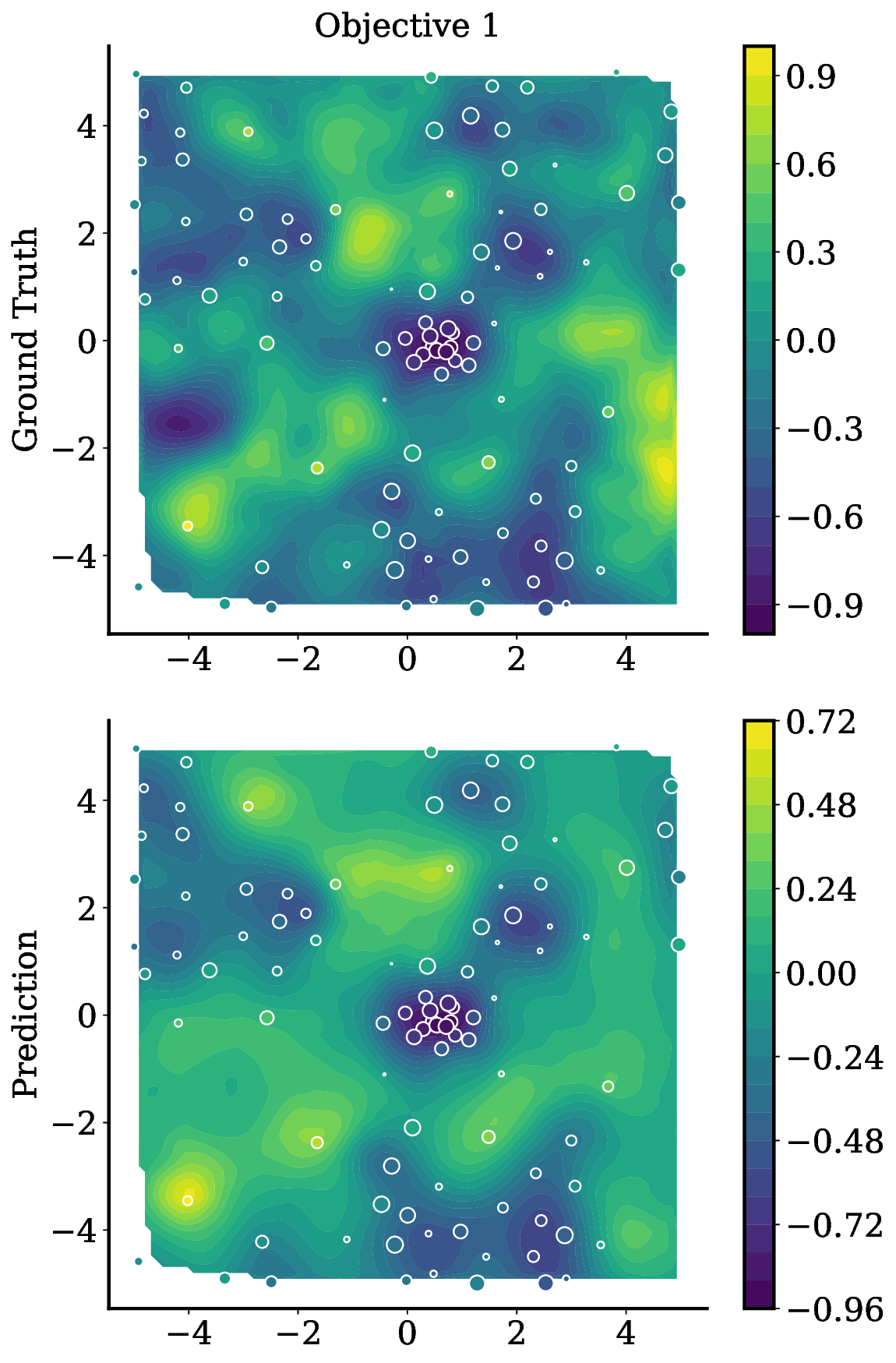

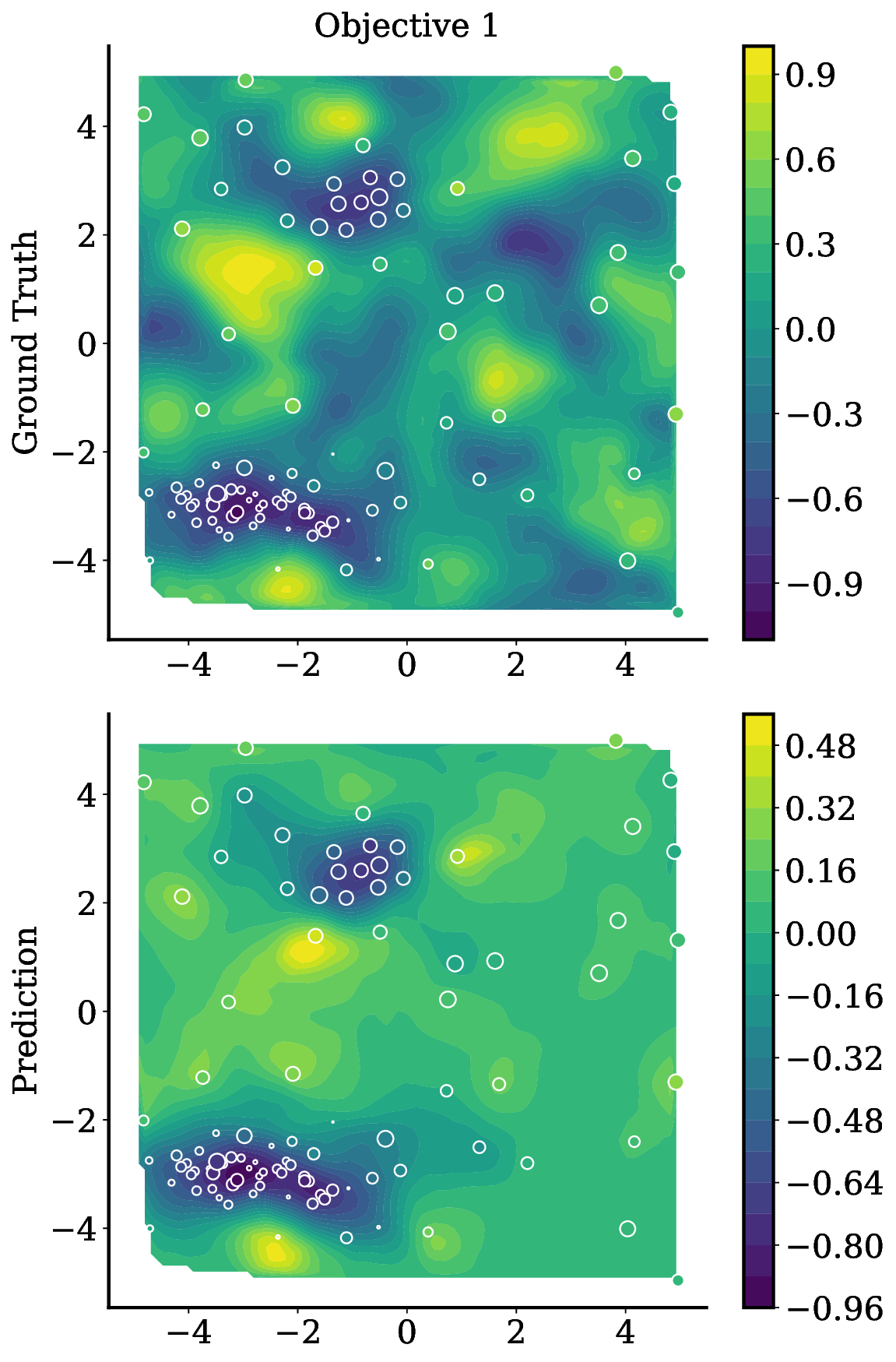

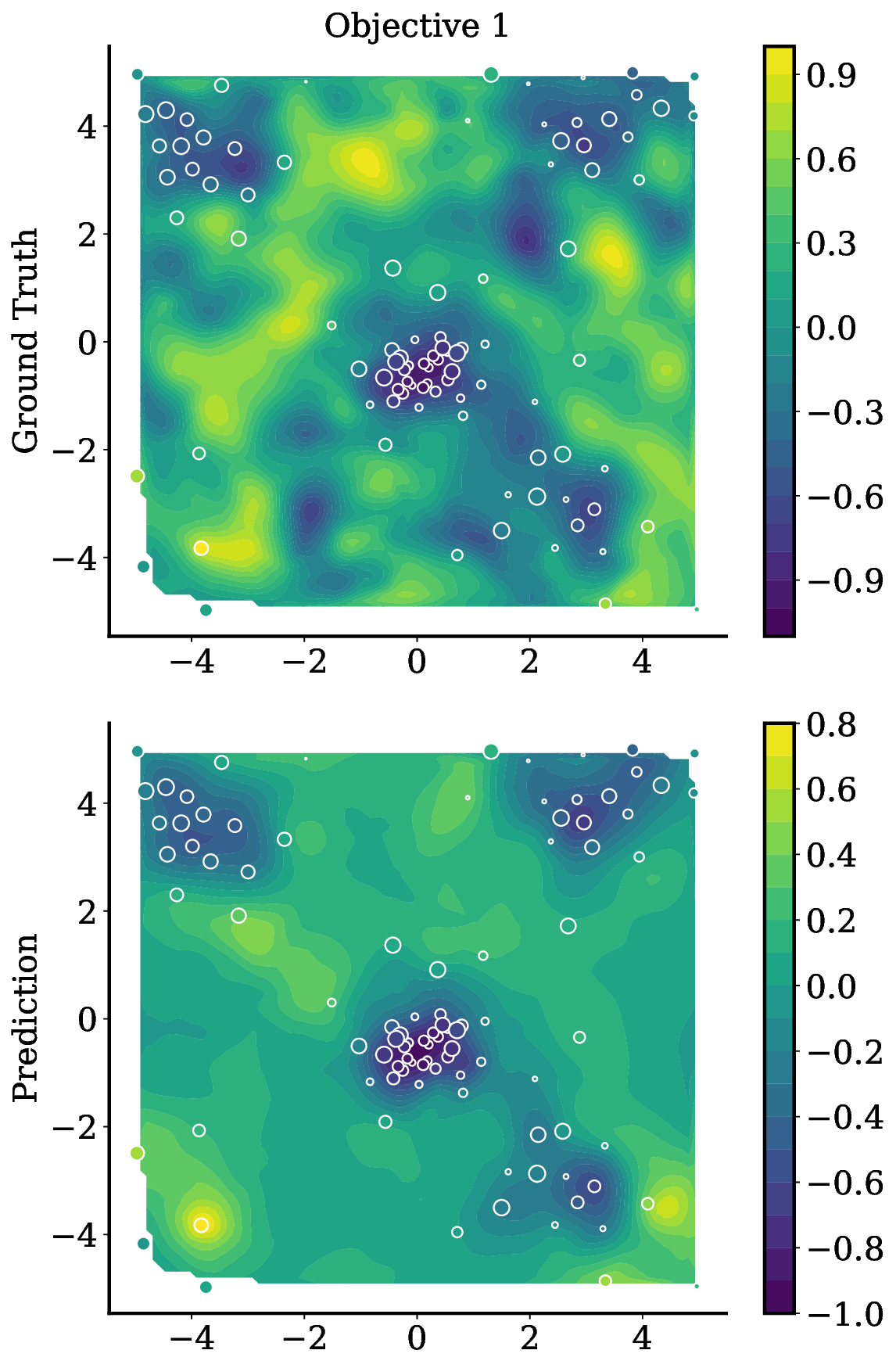

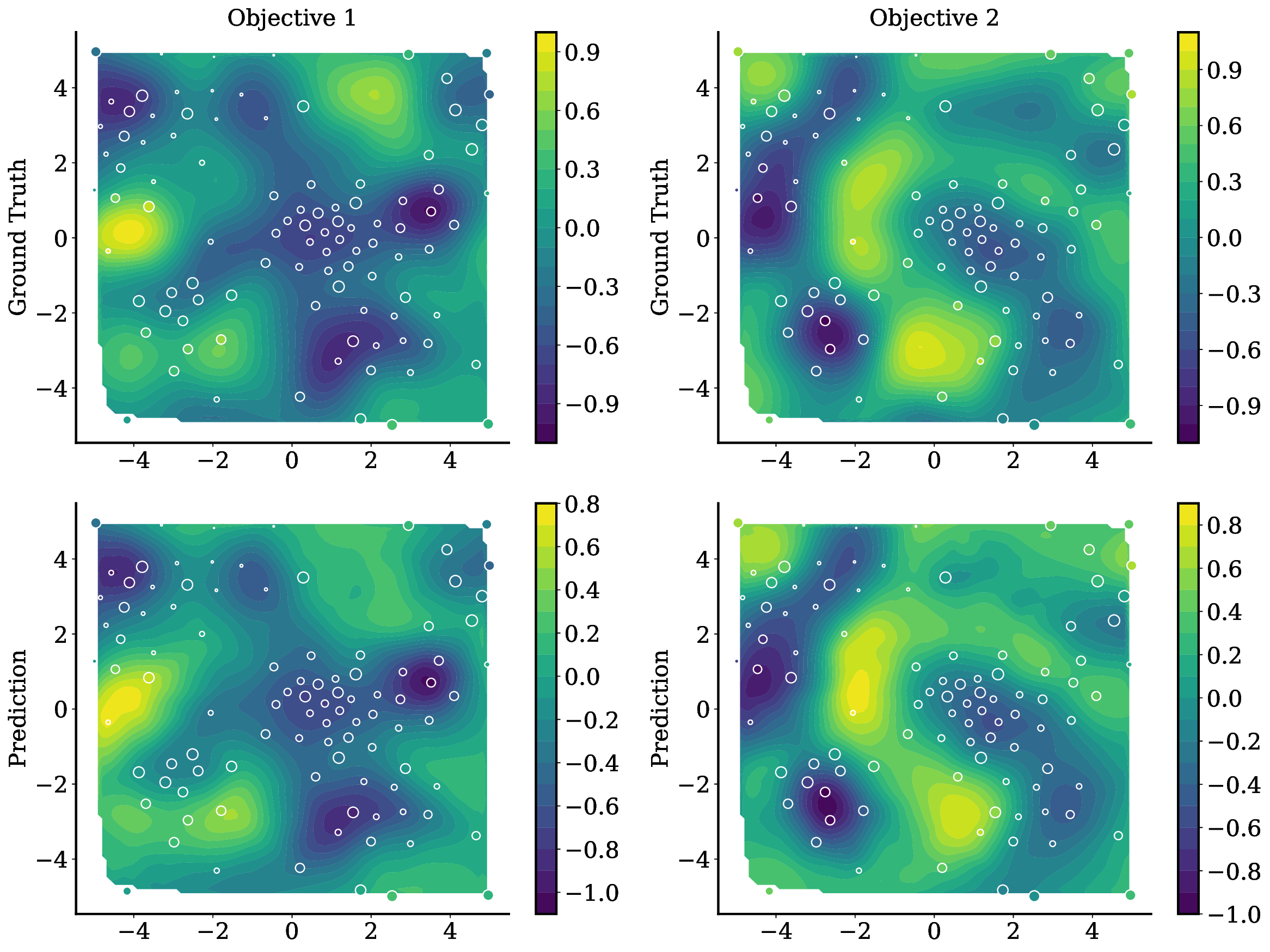

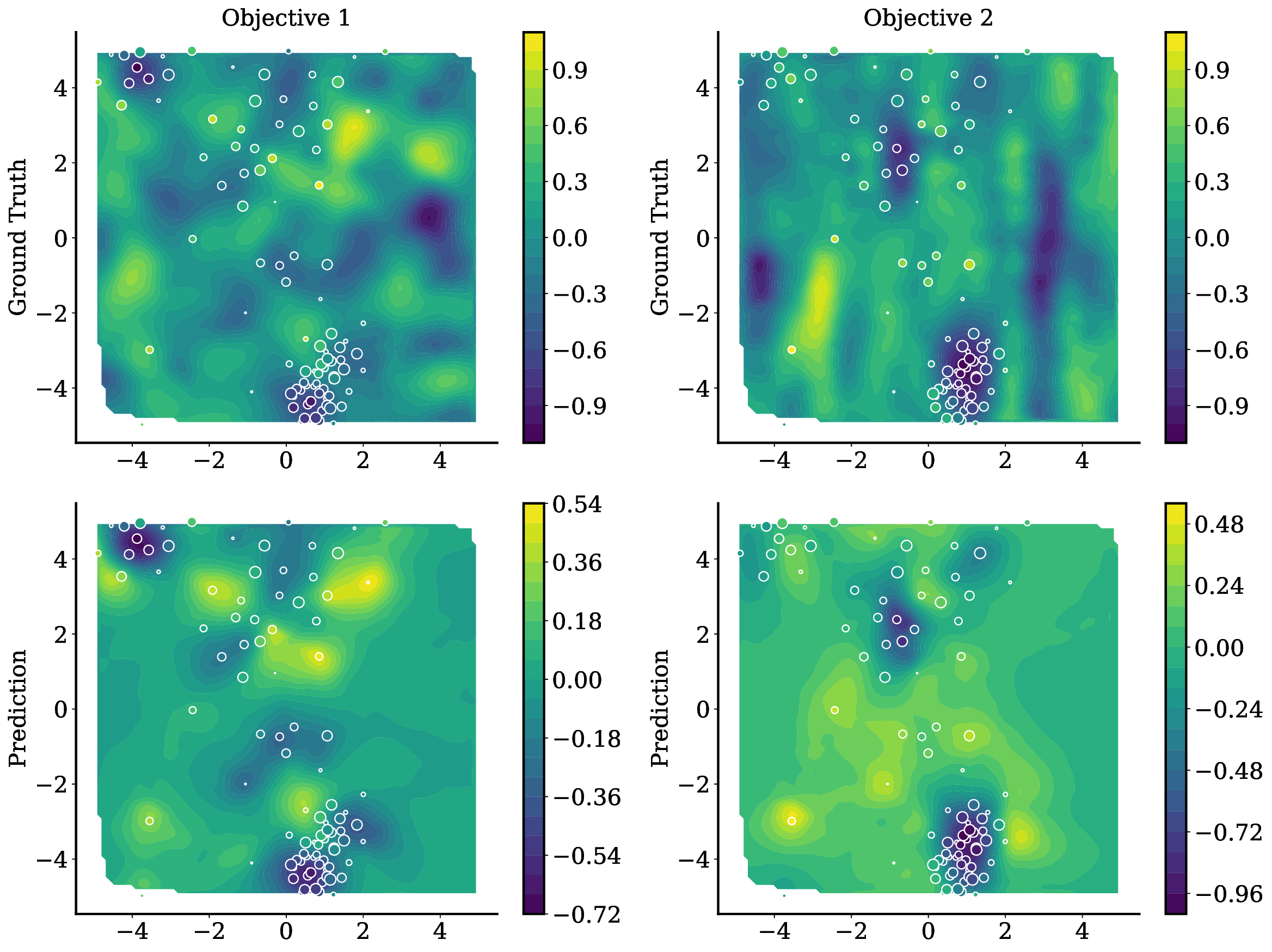

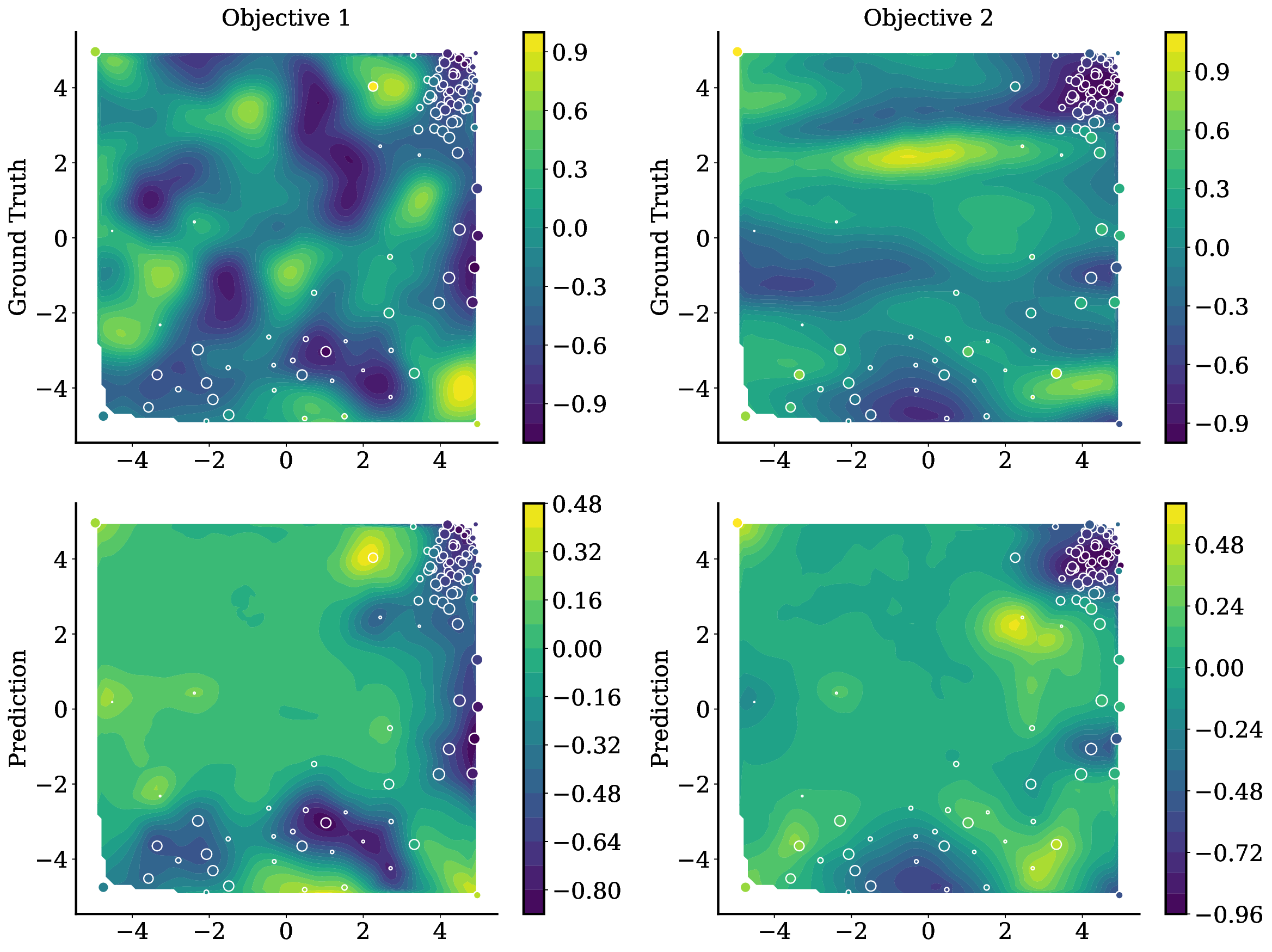

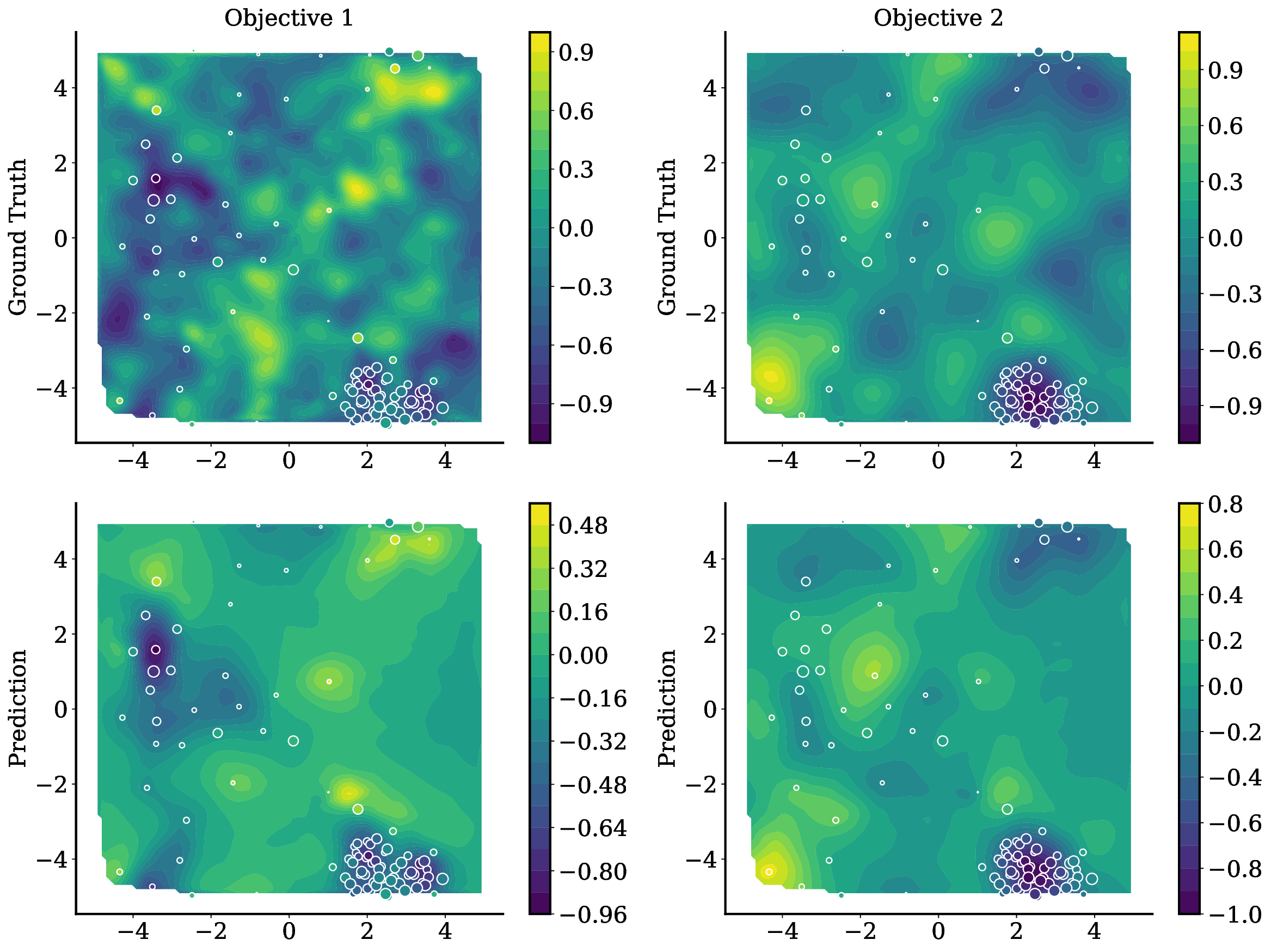

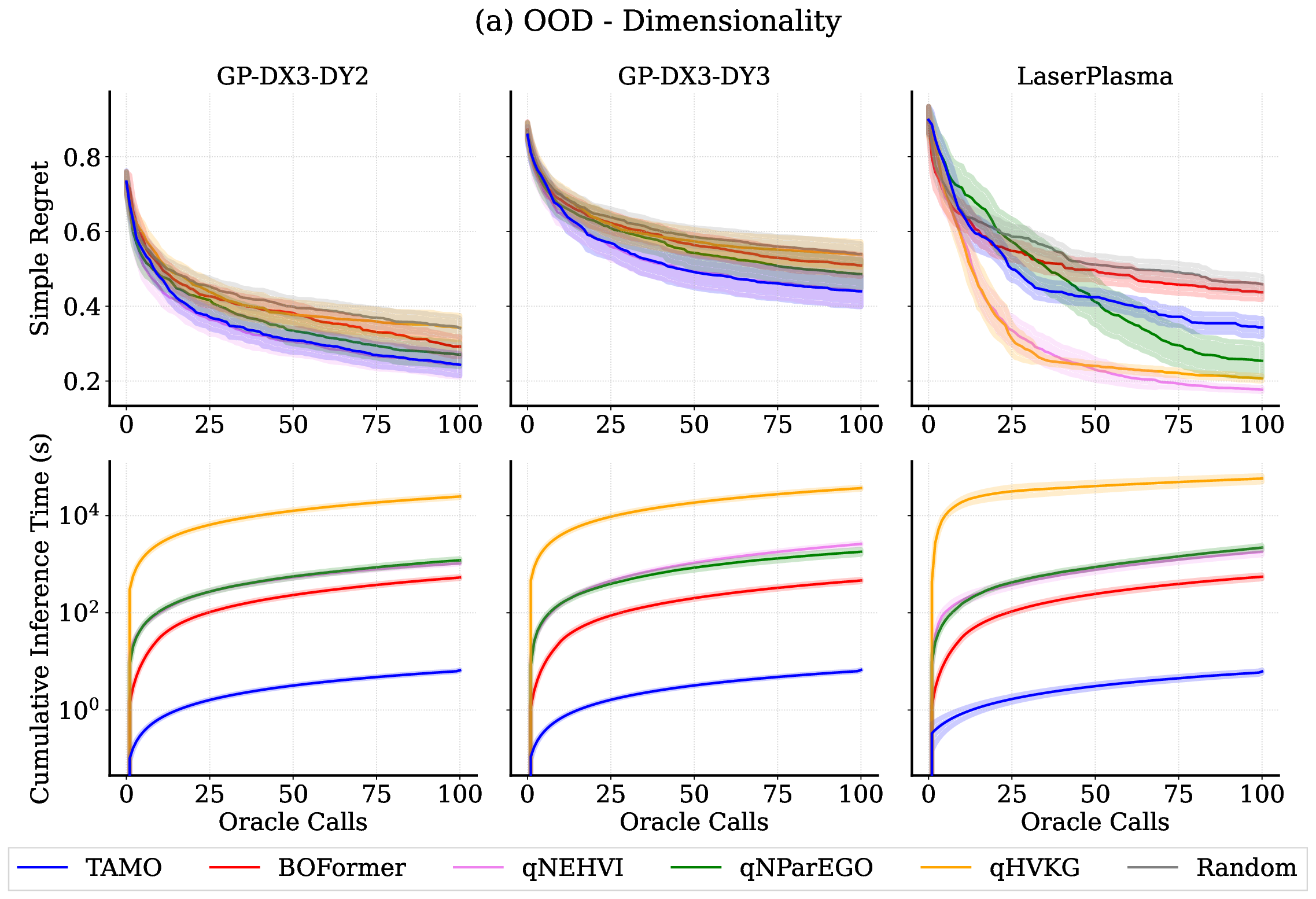

• We introduce TAMO, a fully amortized policy for multi-objective optimization that maps the observed history directly to the next query (Figure 1). Training uses reinforcement learning to optimize a hypervolume-oriented utility over entire trajectories, encouraging long-horizon rather than one-step gains. At inference, proposals are produced by a single forward pass. • TAMO is dimension agnostic on both inputs and outputs: we introduce a transformer architecture with a novel dimension-aggregating embedder that jointly represents all input features and objective values regardless of dimensionality. This enables pretraining on heterogeneous tasks, synthetic or drawn from real meta-datasets, and transfer to new problems without retraining. To our knowledge, this is the first end-to-end, dimension-agnostic architecture for black-box optimization, let alone MOO (Figure 1, bottom).

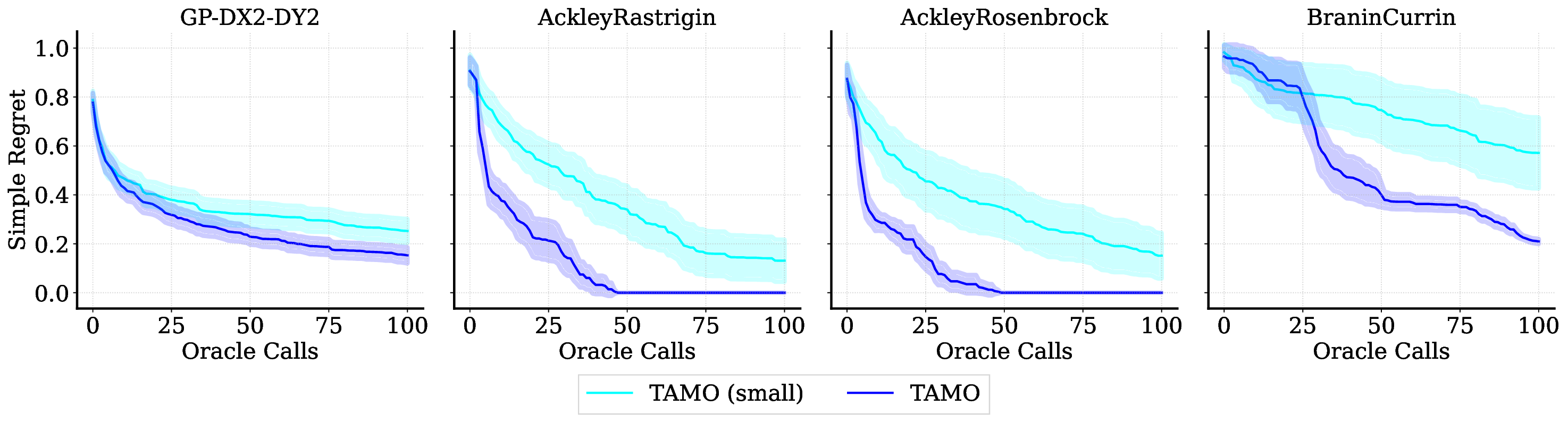

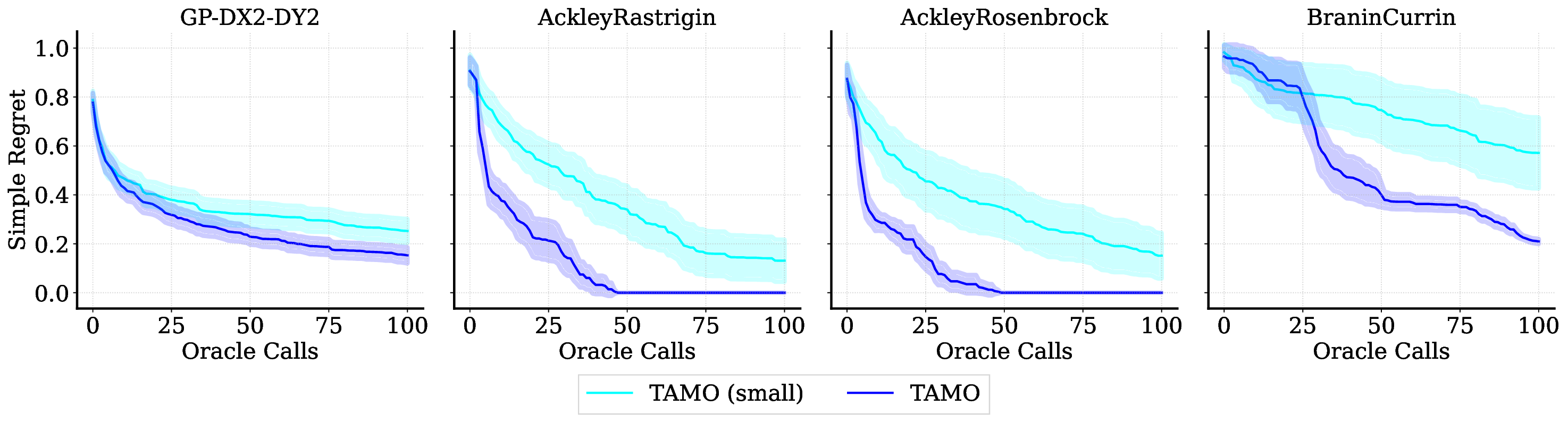

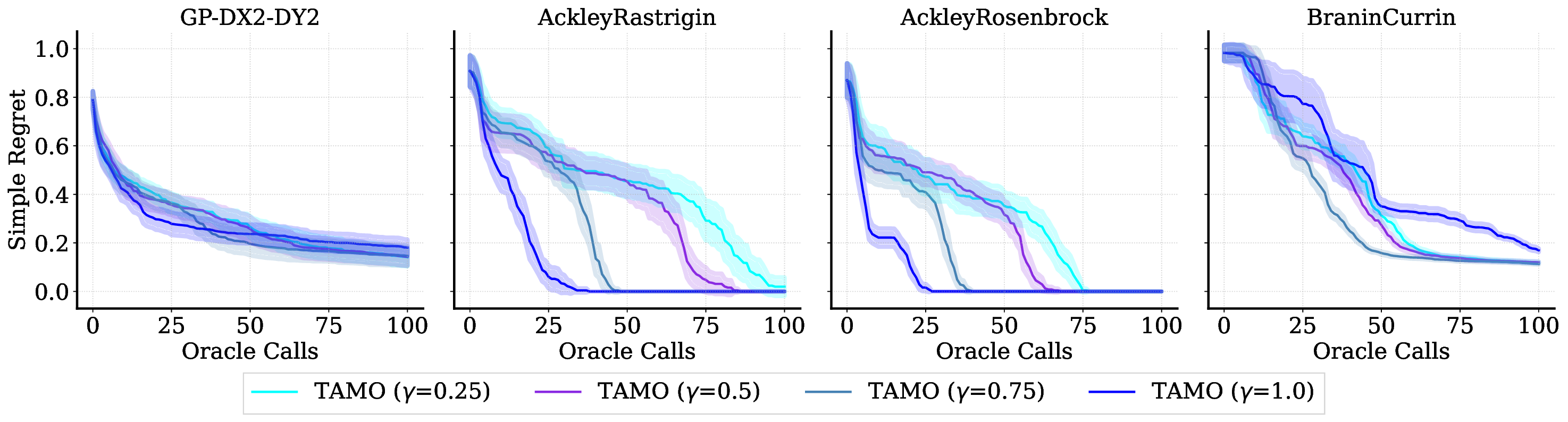

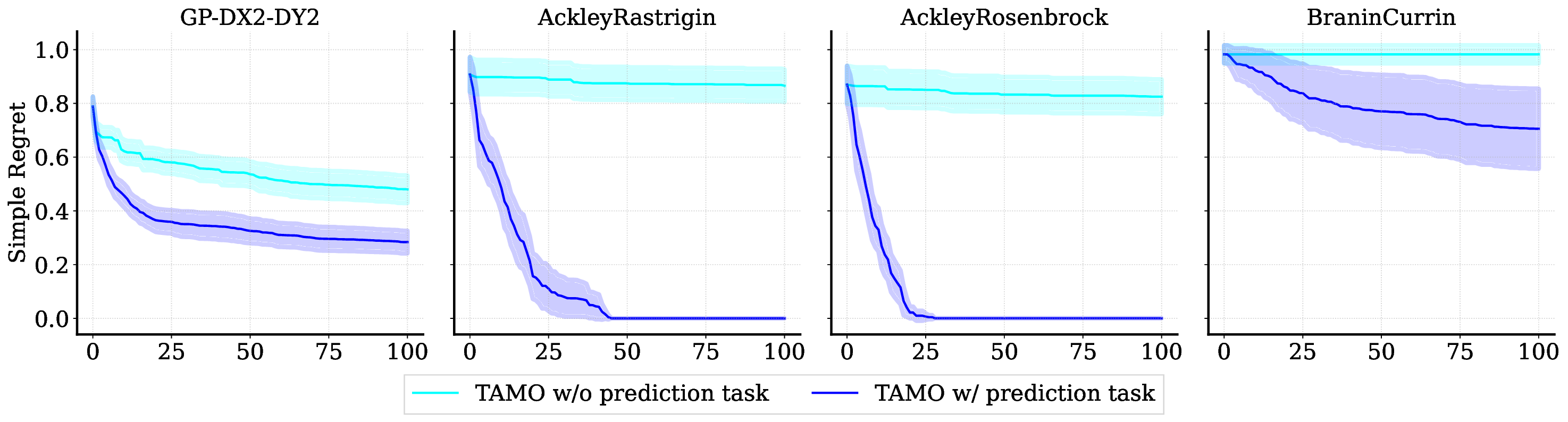

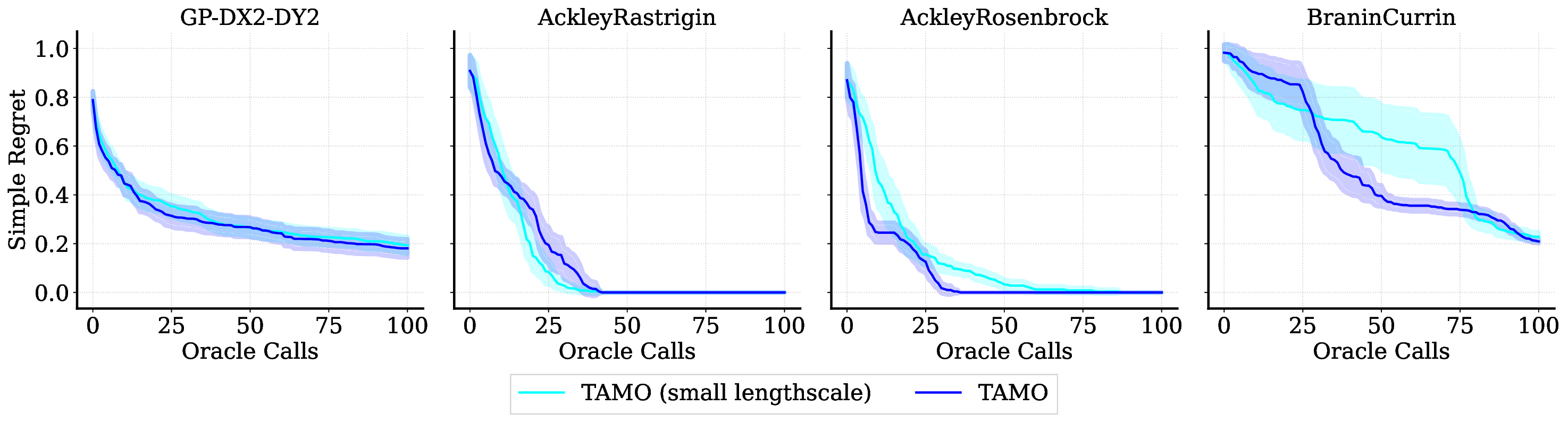

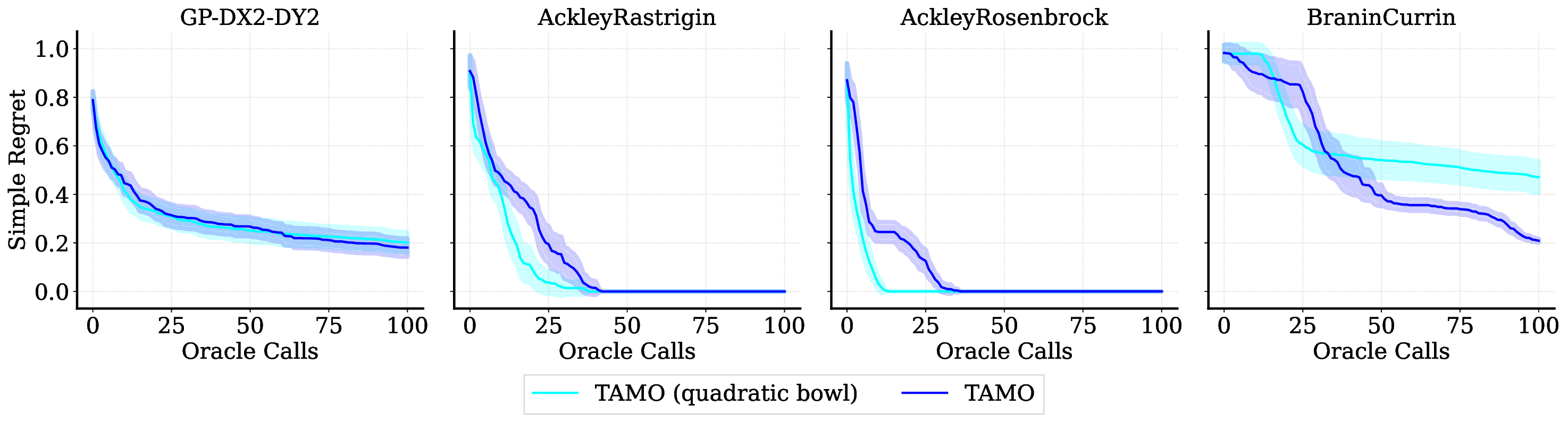

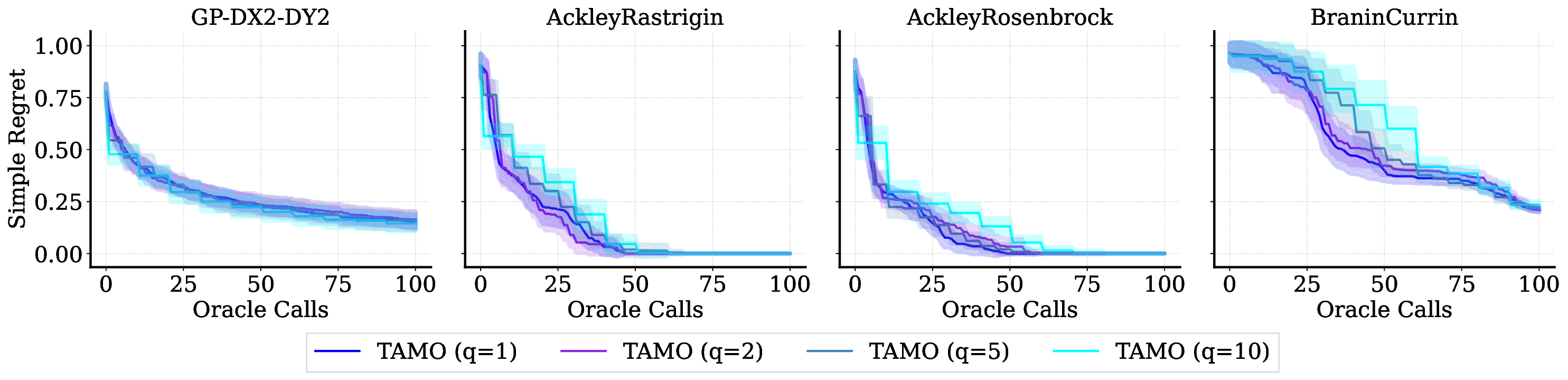

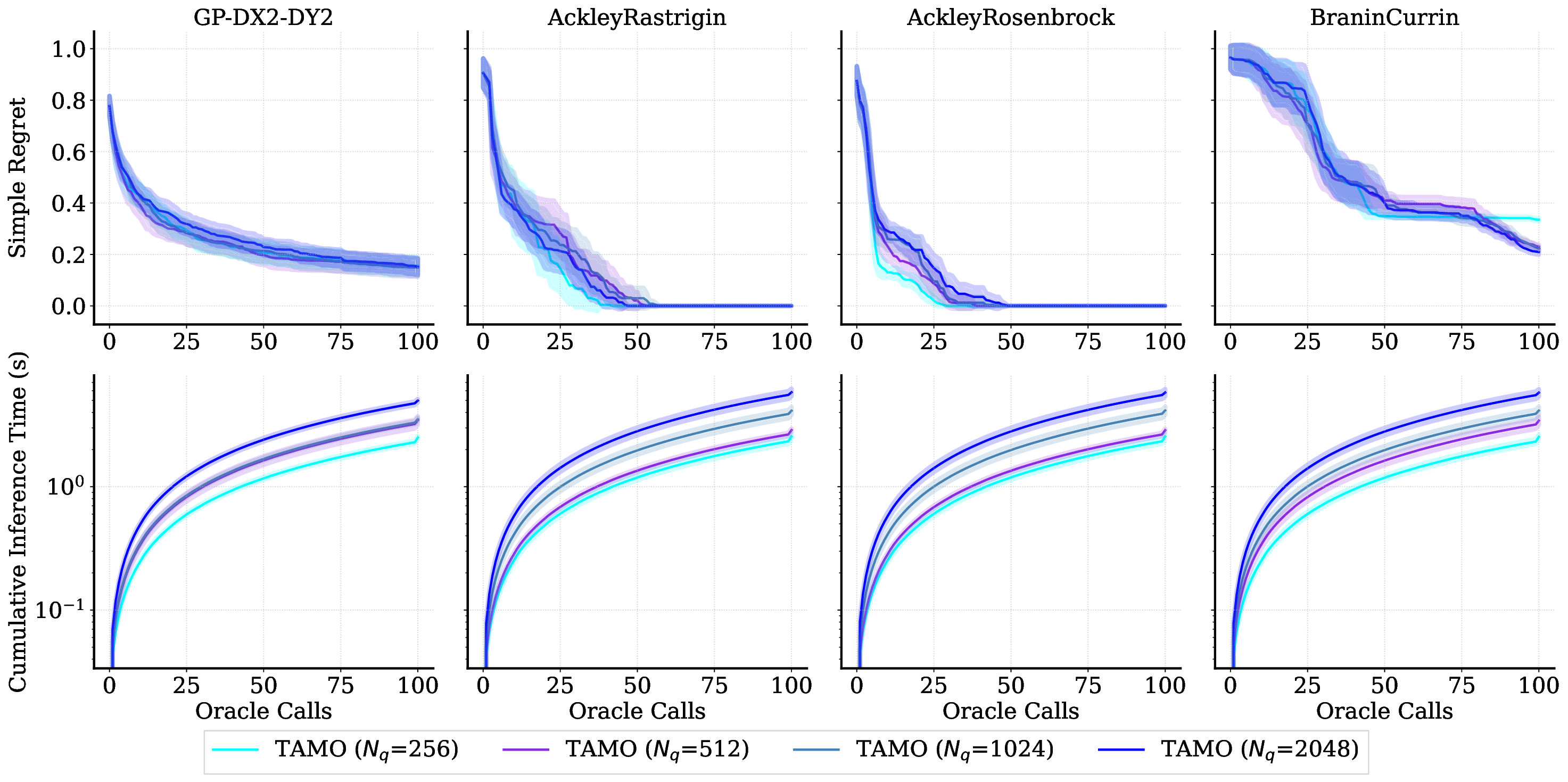

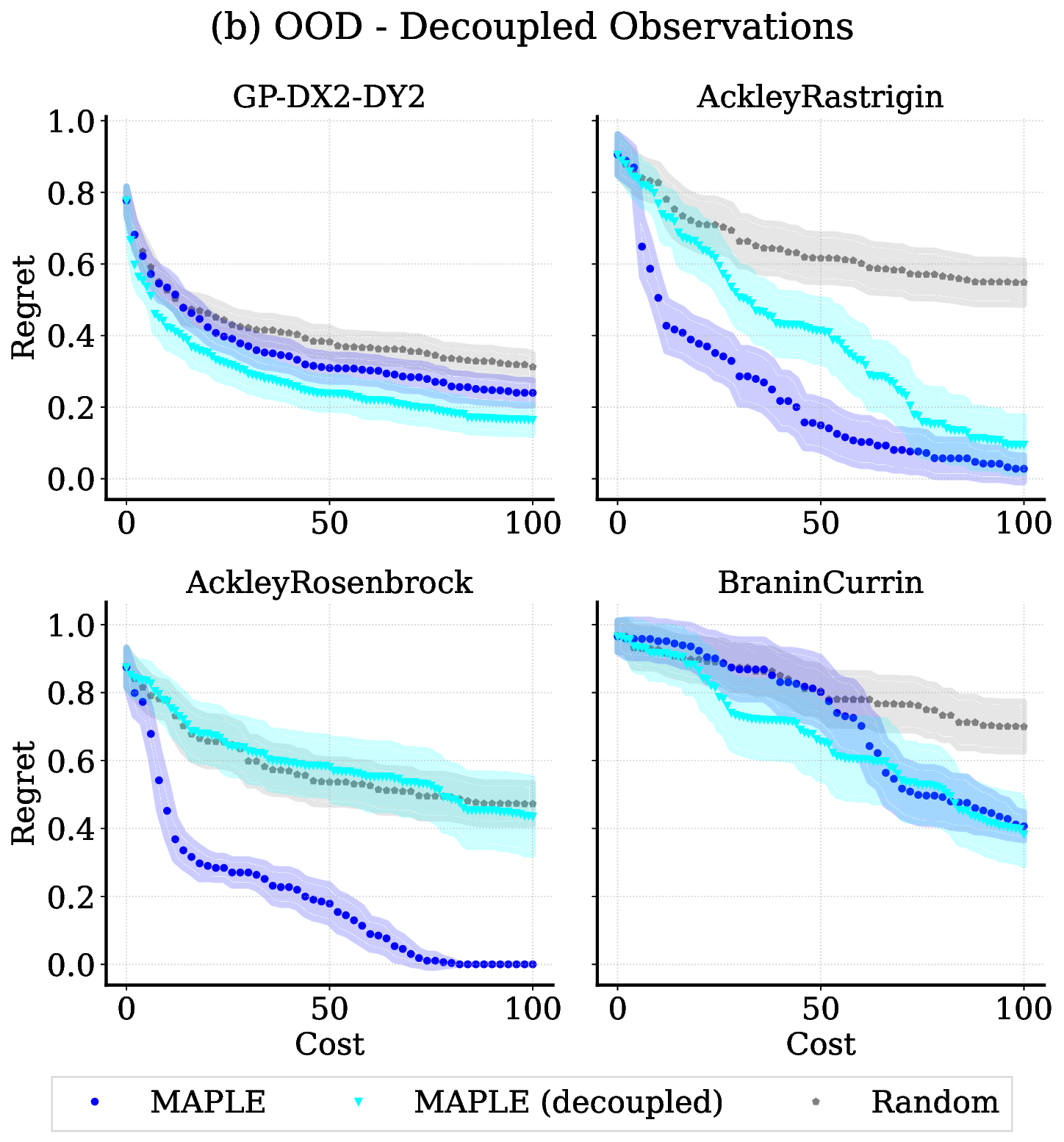

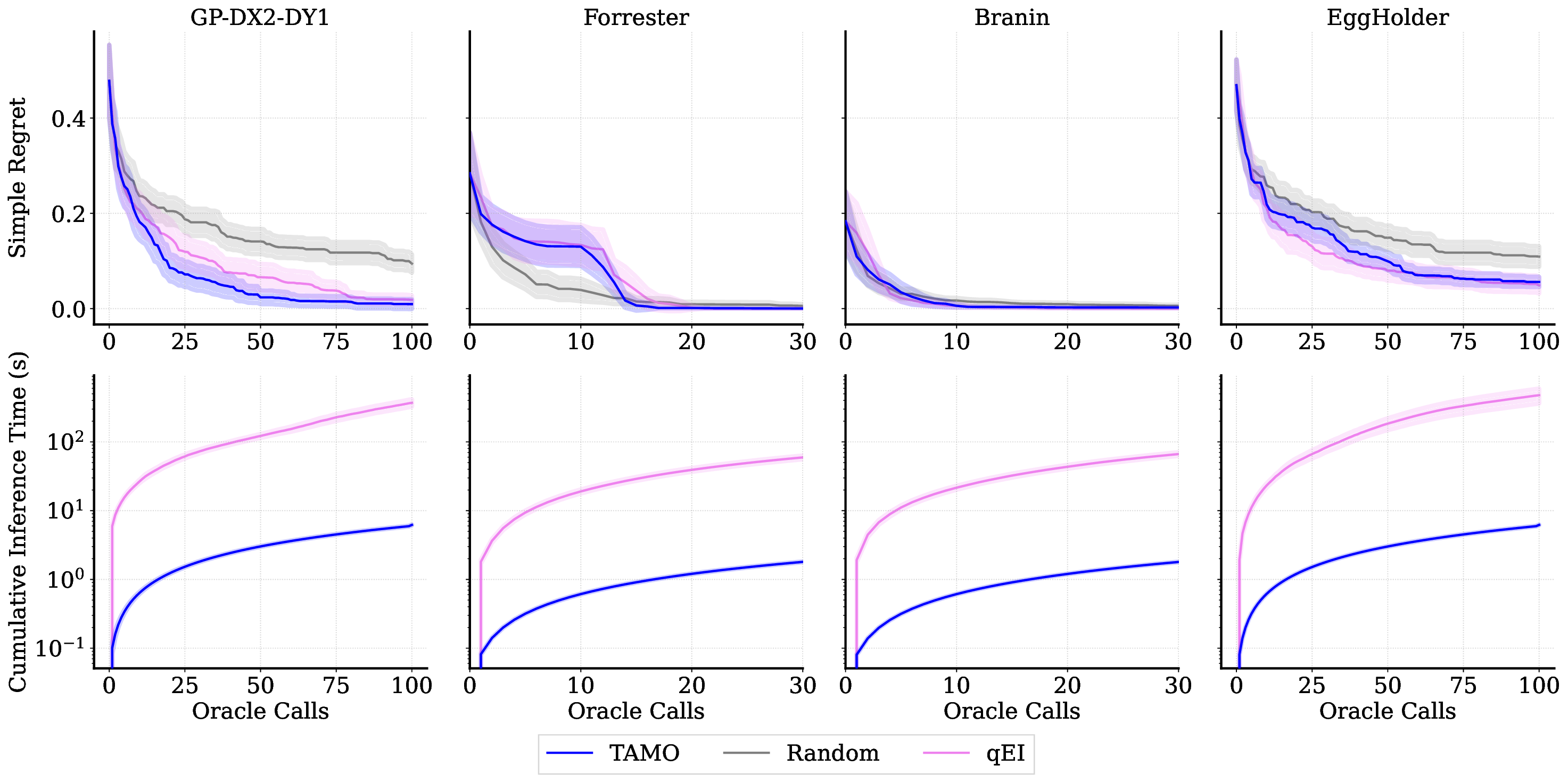

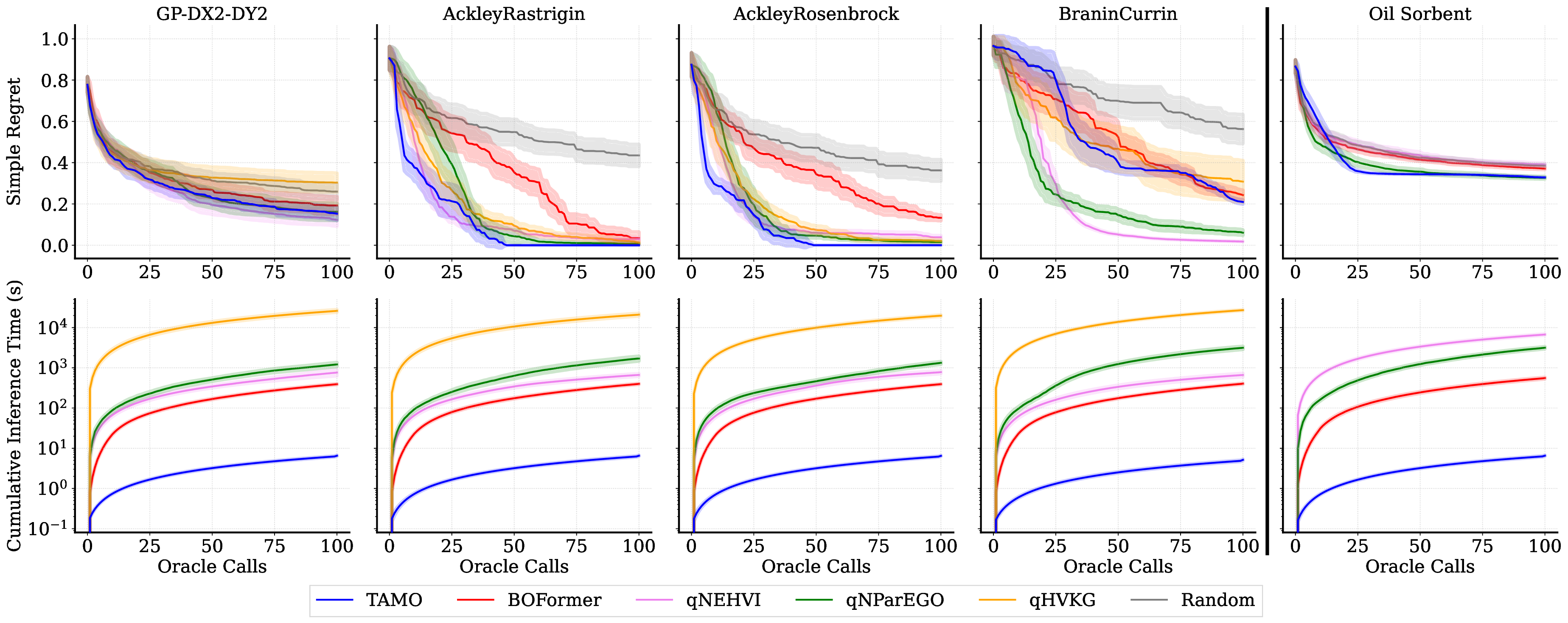

• We evaluate TAMO on synthetic and real multi-objective tasks, observing 50×-1000× lower wall-clock proposal time than GP-based MOBO and baselines such as BOFORMER, which amortizes the acquisition but still relies on task-specific surrogates, while matching Pareto quality and sample efficiency. We further provide an empirical assessment of the generalization capabilities of TAMO, along with its sensitivity to deployment knobs.

Multi-objective Optimization. Consider a multi-objective optimization problem in which one aims to optimize a function f (x) = [f 1 (x), . . . , f dy (x)] ∈ R dy , and observations y = f (x) + ε where X ⊂ R dx is a compact search space. In many practical scenarios, it is not possible to find a single design x that is optimal for all objectives simultaneously. Instead, the notion of Pareto dominance is used to compare objective vectors. An objective vector f (x) Pareto-dominates another vector

. A common goal in multi-objective optimization is to approximate the global frontier P(X ) within a limited budget of T function evaluations. One popular way to assess solution quality is the hypervolume (

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.