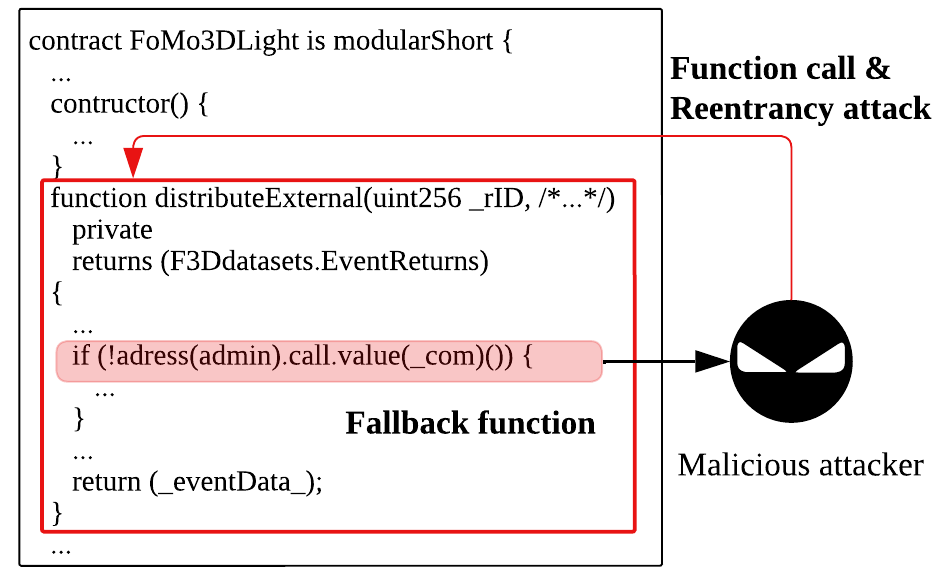

The rapid growth of Ethereum has made it more important to quickly and accurately detect smart contract vulnerabilities. While machine-learning-based methods have shown some promise, many still rely on rule-based preprocessing designed by domain experts. Rule-based preprocessing methods often discard crucial context from the source code, potentially causing certain vulnerabilities to be overlooked and limiting adaptability to newly emerging threats. We introduce BugSweeper, an end-to-end deep learning framework that detects vulnerabilities directly from the source code without manual engineering. BugSweeper represents each Solidity function as a Function-Level Abstract Syntax Graph (FLAG), a novel graph that combines its Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) with enriched control-flow and data-flow semantics. Then, our two-stage Graph Neural Network (GNN) analyzes these graphs. The first-stage GNN filters noise from the syntax graphs, while the second-stage GNN conducts high-level reasoning to detect diverse vulnerabilities. Extensive experiments on real-world contracts show that BugSweeper significantly outperforms all state-of-the-art detection methods. By removing the need for handcrafted rules, our approach offers a robust, automated, and scalable solution for securing smart contracts without any dependence on security experts.

Blockchain is a decentralized and distributed ledger that enables open participation without third-party intermediaries and has attracted significant interest from academia and industry (Krichen et al. 2022). Ethereum extended blockchain capabilities by introducing smart contracts, which are digital agreements written in Solidity code that automatically execute transactions (Buterin et al. 2013). However, these smart-contract programs introduce potential security vulnerabilities that can be exploited by malicious attackers. According to an empirical study (Durieux et al. 2020) that analyzed 47,368 smart contracts, many vulnerabilities, such as reentrancy and unchecked low-level calls, were reported. In particular, the DAO attack (Daian 2016) exploited a reentrancy vulnerability to steal 3.6 million Ether (valued at $60 million at the time). Furthermore, smart contracts cannot be modified once deployed, unlike traditional software. Fixing a deployed contract typically requires deleting the original and redeploying an updated version, which can be both inconvenient and costly. For these reasons, it is crucial to thoroughly verify the security of smart contracts before deployment.

A variety of code-analysis techniques have been proposed to detect vulnerabilities, including static analysis (Tikhomirov et al. 2018;Feist, Greico, and Groce 2019;Wang et al. 2024), symbolic execution (Luu et al. 2016;Mueller 2017;Mossberg et al. 2020), and dynamic execution (Jiang, Liu, and Chan 2018;Choi et al. 2022;Liu et al. 2018). However, these conventional methods heavily rely on manually crafted expert rules, making them ineffective against the rapid emergence of new vulnerabilities that bypass predefined patterns.

To overcome these drawbacks, researchers have increasingly leveraged deep learning models for smart contract vulnerability detection. For instance, Peculiar (Wu et al. 2021) and ReVulDL (Zhang et al. 2023) utilize GraphCodeBERT (Guo et al. 2021), while TMP (Zhuang et al. 2021) and AME (Liu et al. 2021) apply Graph Neural Networks (GNNs). These deep learning-based approaches can reduce analysis time and minimize reliance on expert-crafted rules. However, in a given smart contract, only a small fraction of the code is typically involved in a vulnerability. This observation motivates extracting vulnerability-specific code fragments for training vulnerability detection models. Existing deep learning methods incorporate preprocessing steps for extraction. However, these still depend on rigid, rule-based heuristics, resulting in several limitations:

• Restricted Scope: They overlook vulnerabilities that are not captured by predefined rules. For example, novel variations of reentrancy attacks that deviate from established heuristics may remain undetected. • Poor Generalization: Deep learning models relying on narrow, rule-based preprocessing cannot identify other vulnerability types (e.g., unchecked low-level calls, arithmetic errors) that do not fit existing patterns.

• Information Loss: If preprocessing rules are inaccurately specified, crucial details in the original code may be lost. In this paper, we introduce BugSweeper, a novel graphbased framework for detecting vulnerabilities in smart contracts. BugSweeper employs a GNN trained on our proposed Function-Level Abstract Syntax Graph (FLAG) representation. It effectively identifies various vulnerability types in a fully automated and data-driven manner without relying on predefined expert rules, thereby overcoming the limitations of previous rule-based preprocessing methods.

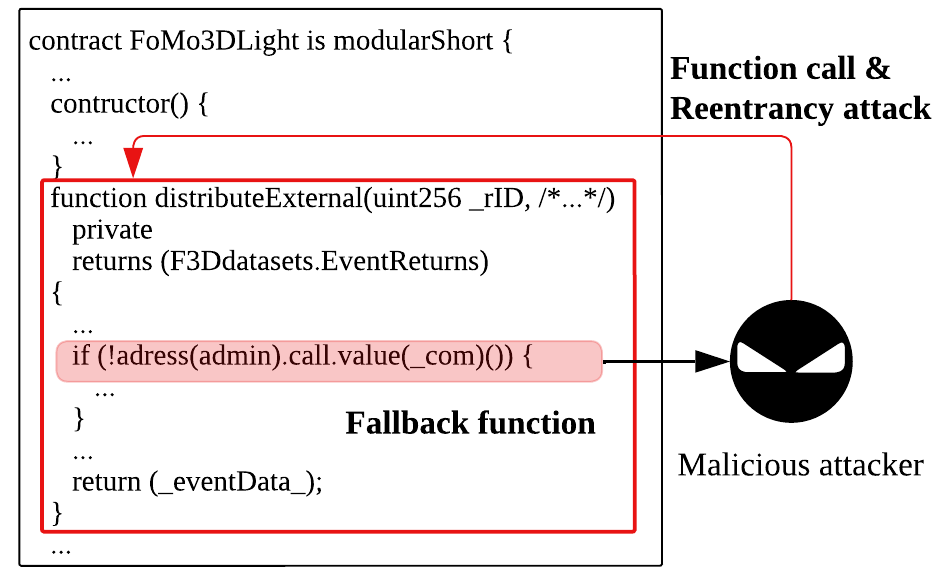

Figure 1 provides an example of a reentrancy attack. In this scenario, the distributeExternal function uses call.value() to send Ether to an external address, which in turn triggers the fallback function of a malicious contract. The fallback function-a default function that executes when no other function matches, or when Ether is received-then repeatedly calls distributeExternal, causing it to re-enter and execute again before the previous invocation completes. Such cases illustrate that many security vulnerabilities in smart contracts arise from unsafe interfunction interactions. Inspired by this observation and motivated by the limitations of current rule-based preprocessing methods, we propose analyzing smart contracts at the function level for more precise vulnerability detection.

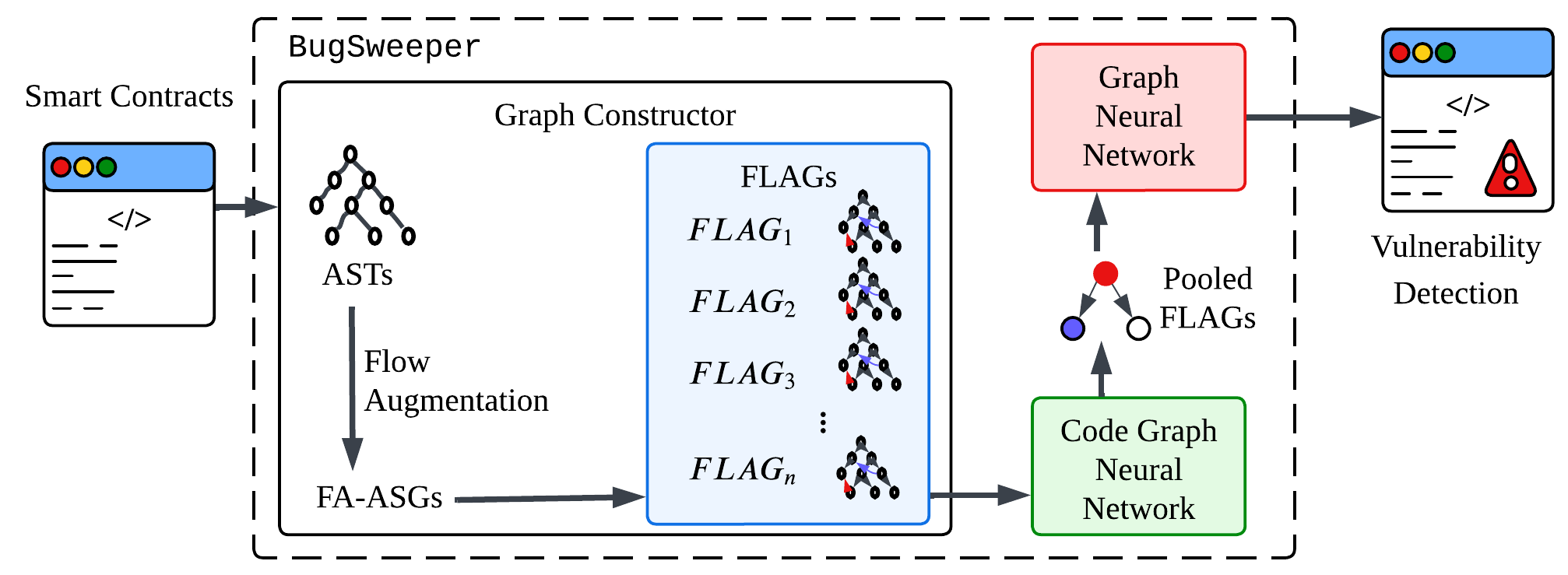

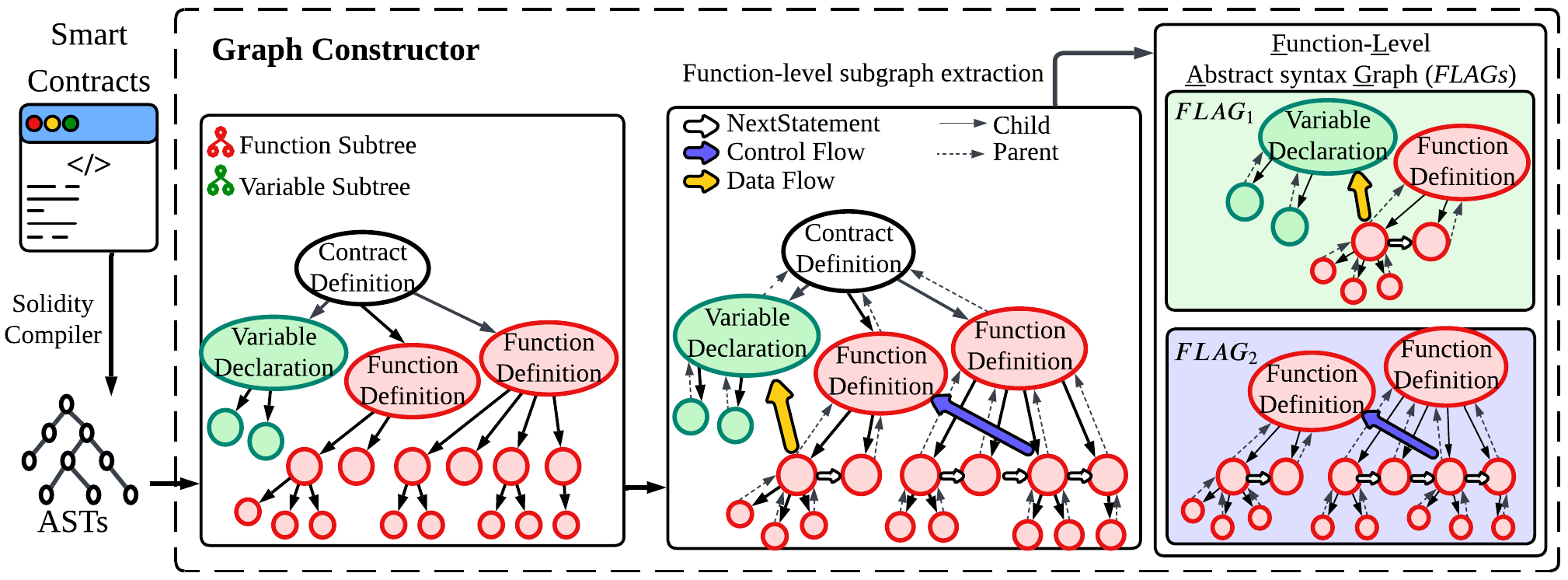

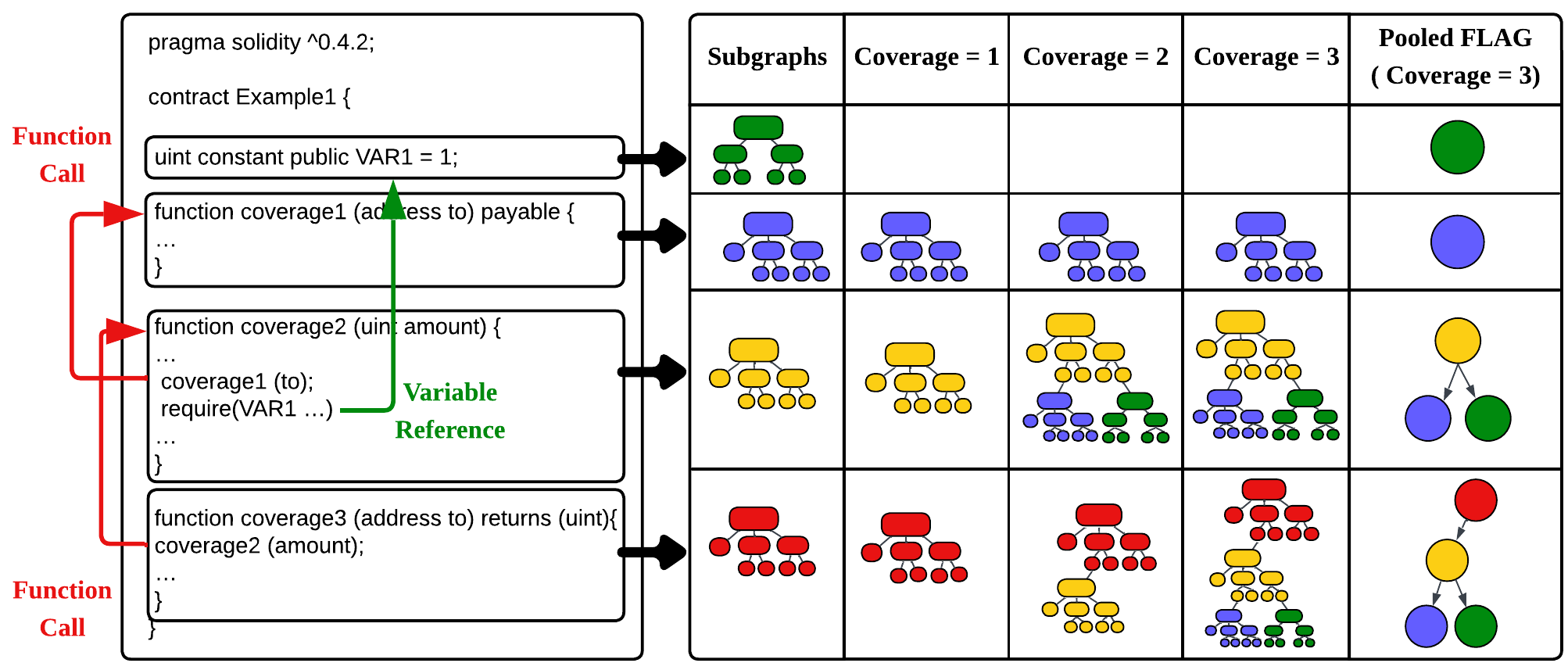

While analyzing code at the function level provides precise details, it neglects important connections between functions and still leads to redundant information. To solve this, we first convert Solidity code into abstract syntax trees (ASTs) and then divide these trees into separate function-level subtrees. We enrich these subtrees by adding edges representing function calls and variable references, creating FLAGs. Additionally, we introduce a parameter called coverage to control the number of inter-function connections included.

However, higher coverage settings introduce extra noise, complicating the lea

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.