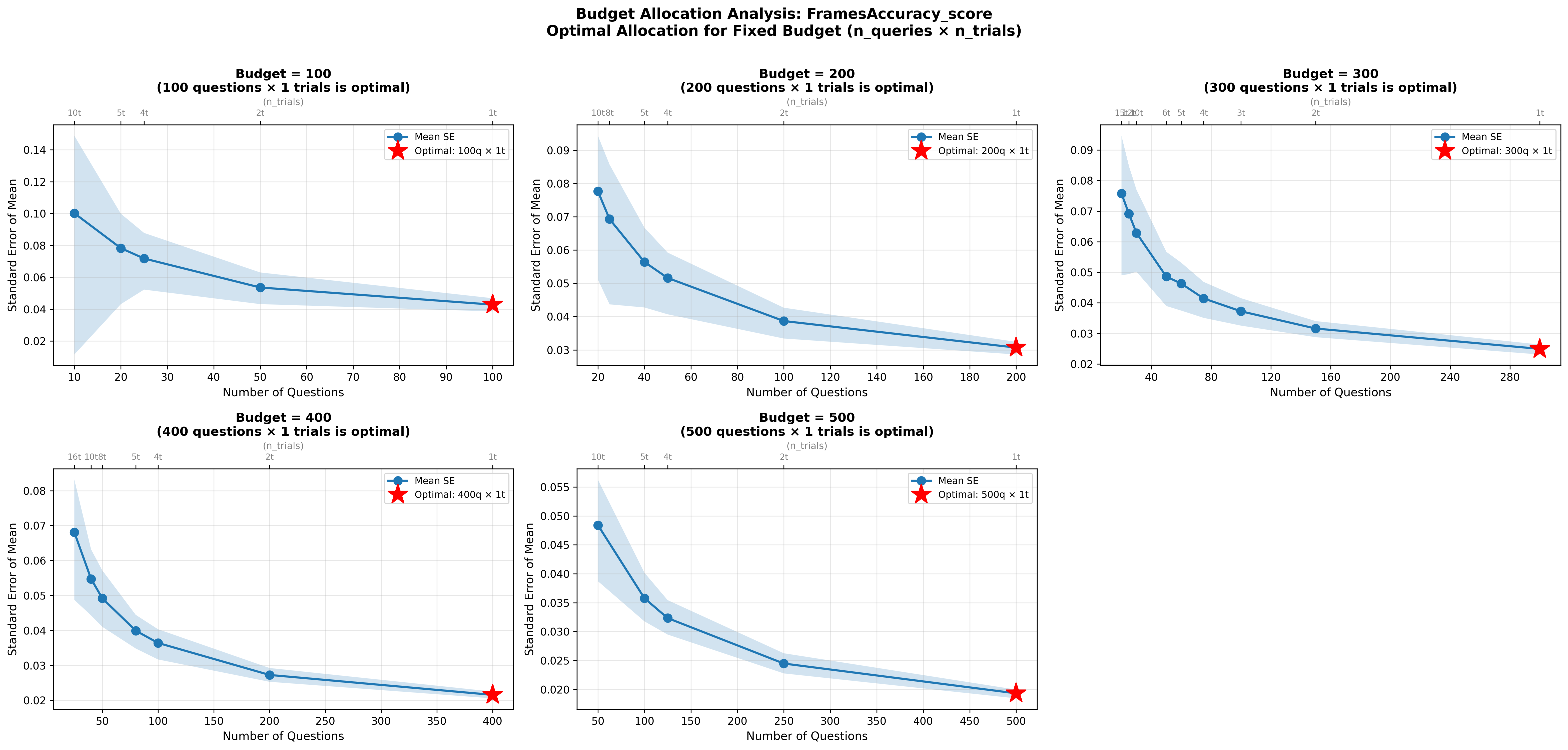

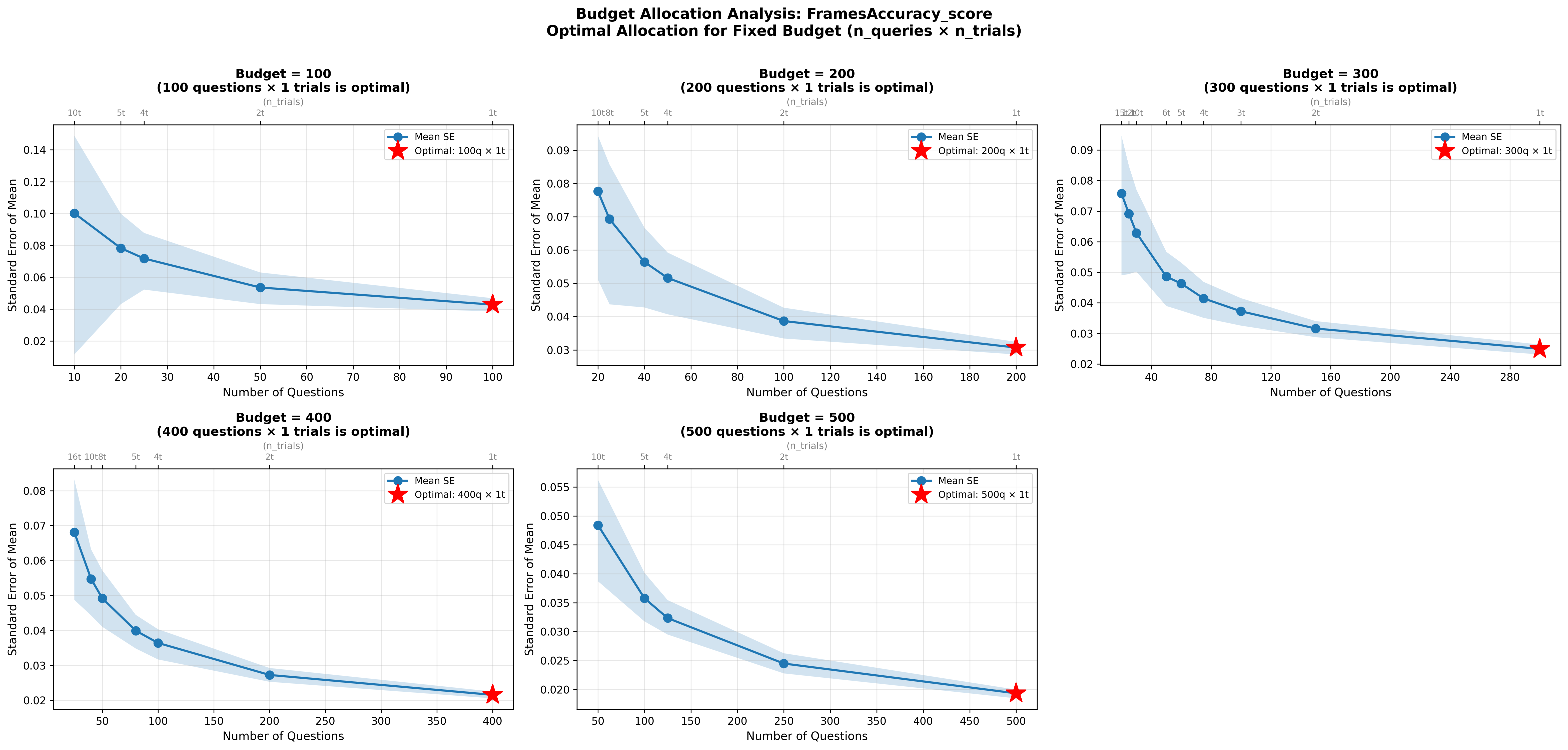

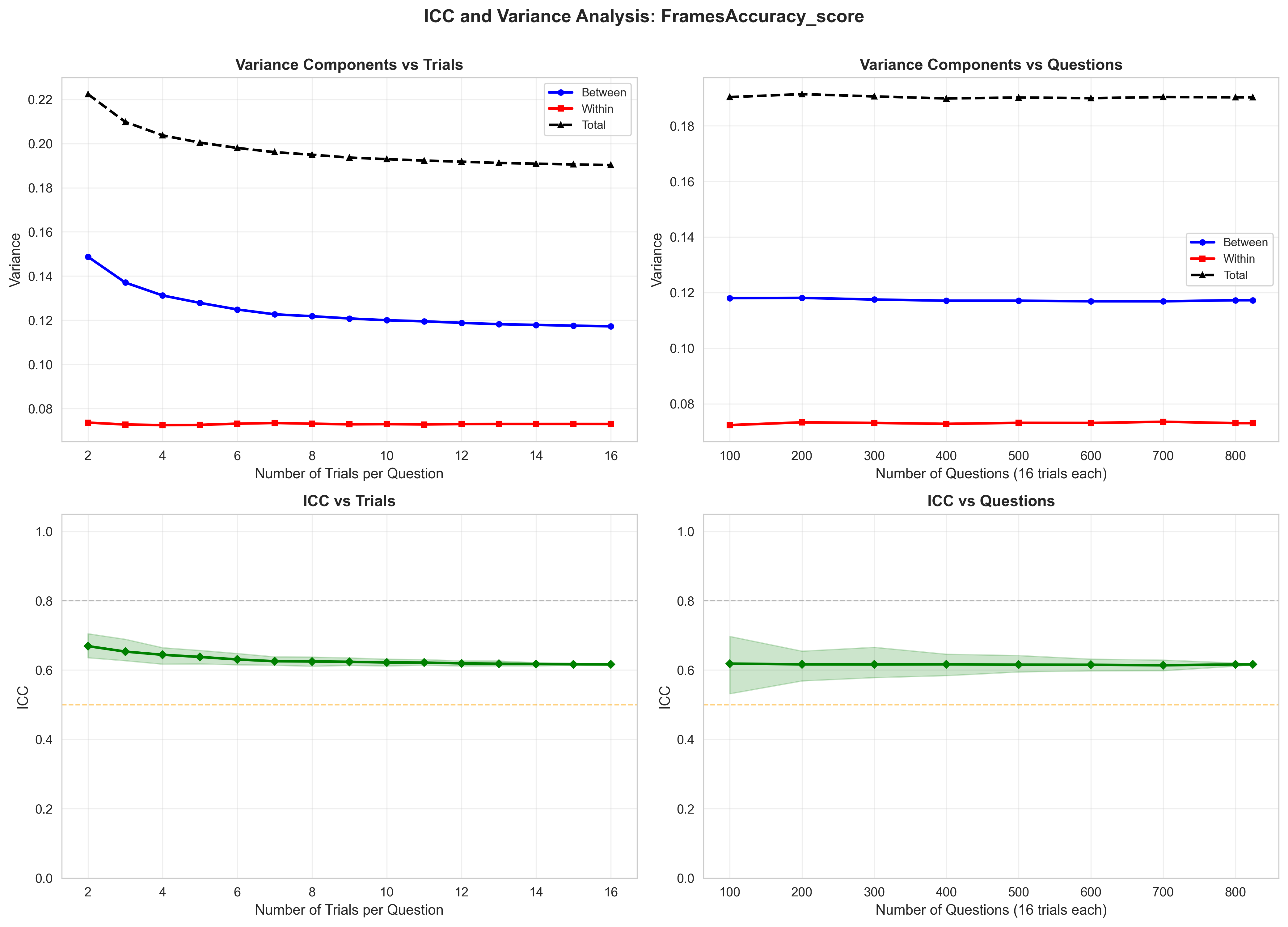

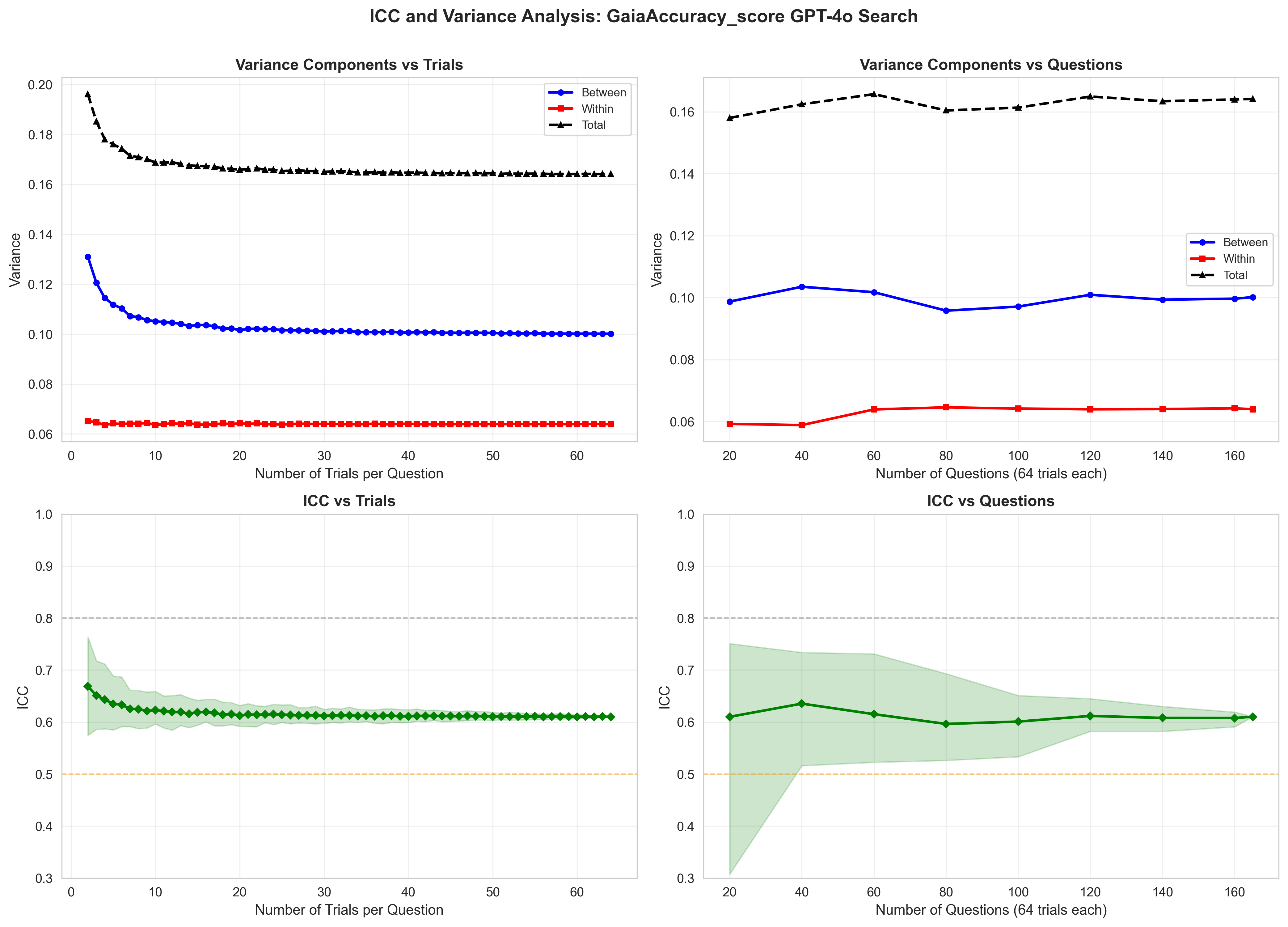

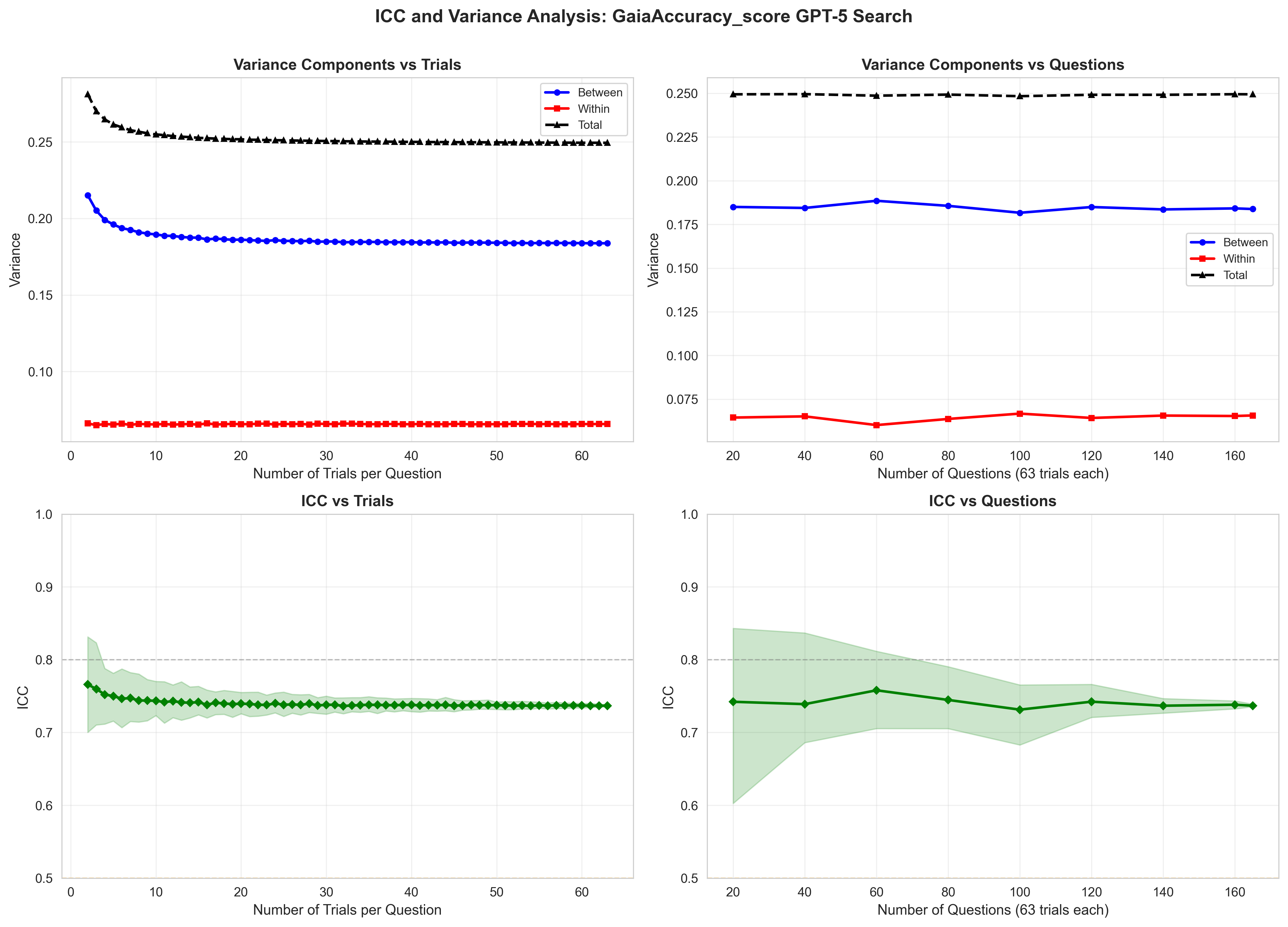

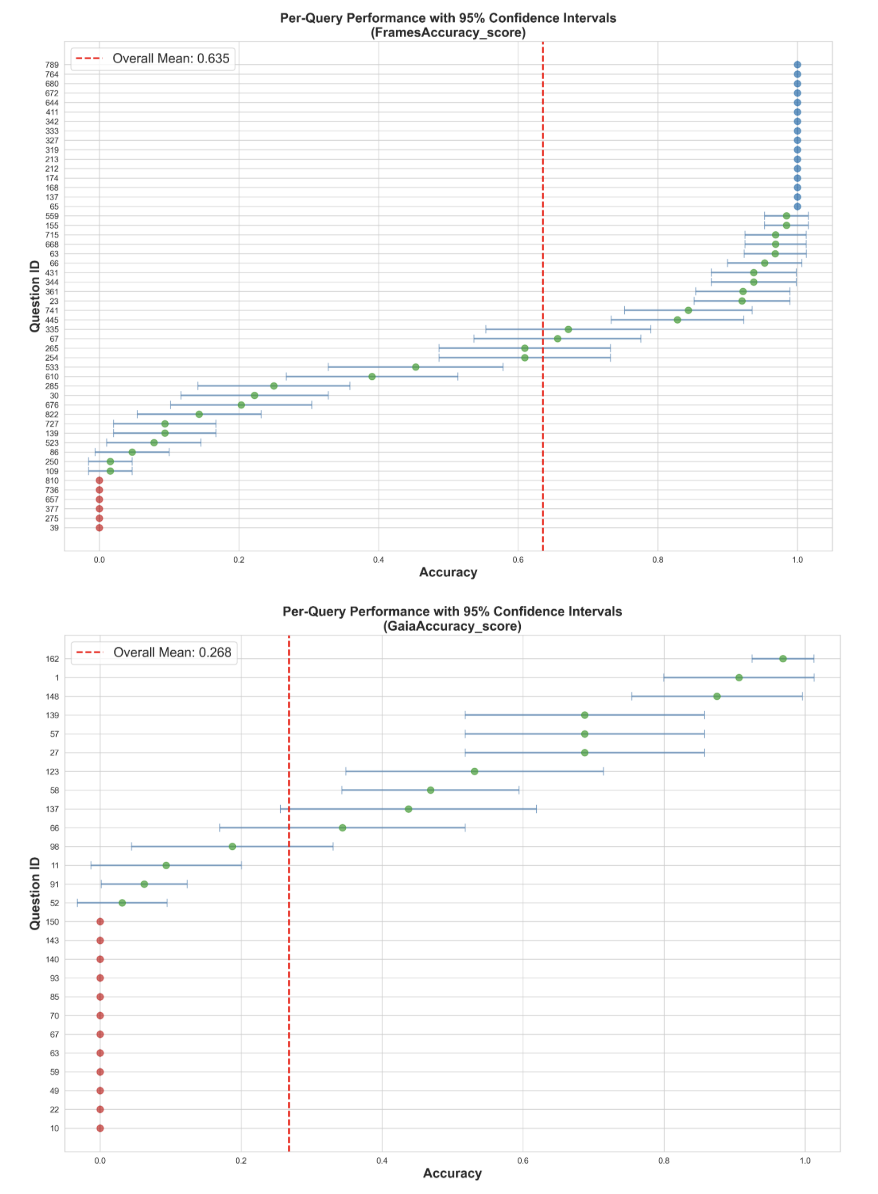

As large language models become components of larger agentic systems, evaluation reliability becomes critical: unreliable sub-agents introduce brittleness into downstream system behavior. Yet current evaluation practice, reporting a single accuracy number from a single run, obscures the variance underlying these results, making it impossible to distinguish genuine capability improvements from lucky sampling. We propose adopting Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC), a metric from measurement science, to characterize this variance. ICC decomposes observed variance into between-query variance (task difficulty) and within-query variance (agent inconsistency), highlighting whether reported results reflect true capability or measurement noise. We evaluated on GAIA (Levels 1-3, measuring agentic capabilities across varying reasoning complexity) and FRAMES (measuring retrieval and factuality across multiple documents). We found that ICC varies dramatically with task structure, with reasoning and retrieval tasks (FRAMES) exhibit ICC=0.4955-0.7118 across models, and agentic tasks (GAIA) exhibiting ICC=0.304-0.774 across models. For sub-agent replacement decisions in agentic systems, accuracy improvements are only trustworthy if ICC also improves. We demonstrate that ICC converges by n=8-16 trials for structured tasks and n>=32 for complex reasoning, enabling practitioners to set evidence-based resampling budgets. We recommend reporting accuracy alongside ICC and within-query variance as standard practice, and propose updated Evaluation Cards capturing these metrics. By making evaluation stability visible, we aim to transform agentic benchmarking from opaque leaderboard competition to trustworthy experimental science. Our code is open-sourced at https://github.com/youdotcom-oss/stochastic-agent-evals.

Large language models (LLMs) are no longer confined to static text prediction. Increasingly, they act as agents: using tools, interacting with environments, and carrying out multistep plans. To measure such capabilities, the field has turned to agentic evaluations Yehudai et al. (2024), Zhang et al. (2024), and Xu et al. (2023). These benchmarks are rapidly becoming reference points for progress. Yet the way they are currently used reduces complex stochastic processes to a single leaderboard number. That number, typically an accuracy or success rate from one run, obscures the variance that determines whether the result is reproducible at all Miller (2024) Li et al. (2025).

Agentic evaluations should be approached as experiments, with outcomes analyzed for variability and reproducibility. Reported performance is often based on a single trial of an inherently random process, with little visibility into uncertainty. Sources of randomness include sampling inside the language model, the behavior of external APIs, and the design of the scoring function. Without accounting for these factors, comparisons across agents risk overstating differences and underestimating variability.

We examine the stochasticity of agentic evaluations using GAIA and FRAMES as running case studies. Replicating these benchmark runs across multiple trials and all three difficulty levels shows that evaluation stability varies significantly with task complexity and model capability, a finding obscured by current single-run reporting practices. Our contribution is both diagnostic and prescriptive: we diagnose why current evaluations are fragile, and we propose ICC (intraclass correlation coefficient) as a metric practitioners can use to characterize and report on evaluation stability, enabling more principled experimental design for agentic benchmarks.

Agentic evaluations differ in structure from static NLP benchmarks. Whereas traditional benchmarks test a model’s ability to map an input to a single output, agentic settings involve multi-step decision making, tool use, and interactions with dynamic environments. An agent may need to query an API, manipulate files, or perform calculations before arriving at an answer. These differences make agentic evaluations richer, but also more sensitive to randomness.

Current practice has yet to reflect this added complexity. Many benchmarks report results from a single run per agent, without confidence intervals, standard errors, or replication. Some studies attempt to reduce bias from agent inconsistency by reporting average@k values (where k=3), but still do so without providing confidence intervals or statistical significance measures (Yao et al. (2024)Team (2025)). Comparisons between agents are frequently made without statistical testing, and scoring functions are not always de-fined in detail. As a result, observed differences may partly reflect random variation, scorer choices, or agent inconsistency rather than genuine differences in capability.

Recent work has begun to address this gap. Miller (2024) provides a statistical treatment of LLM evaluations, deriving estimators and error formulas and recommending resampling protocols. Platforms such as Chatbot Arena and Arena-Lite have introduced bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals into leaderboards Li et al. (2025), highlighting that uncertainty can be made visible at scale. Blackwell, Barry, and Cohn (2024) argue for explicit uncertainty quantification and reproducible protocols in LLM benchmarking, while bow (2025) caution against naive reliance on the Central Limit Theorem in small benchmarks due to undercoverage. More broadly, surveys of evaluation methodologies for LLM-based agents emphasize the lack of standardized protocols and reproducibility practices Yehudai et al. (2025).

The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) (Shrout and Fleiss 1979;McGraw and Wong 1996) has been widely used in psychometrics and medical research to assess measurement reliability by decomposing variance into betweensubject and within-subject components. Koo and Li (2016) provide guidelines for selecting and interpreting ICC variants across different study designs. While ICC is standard practice for evaluating inter-rater reliability and test-retest consistency in clinical settings, it has not been systematically applied to agentic AI evaluation, where variance arises from both task difficulty and agent stochasticity.

Beyond statistical treatments, several strands of prior work contextualize our analysis. Large-scale benchmarks such as BIG-bench Srivastava et al. (2022) and Liang et al. (2022) established multi-dimensional evaluation but did not incorporate statistical testing. MT-Bench Zheng et al. (2023) popularized human-LLM comparison, again without replication. Infrastructure projects such as the lm-eval-harness Gao et al. (2021), OpenAI Evals Chen et al. (2023), and Dynabench Kiela et al. (2021) emphasize standardization and robustness, though they rare

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.