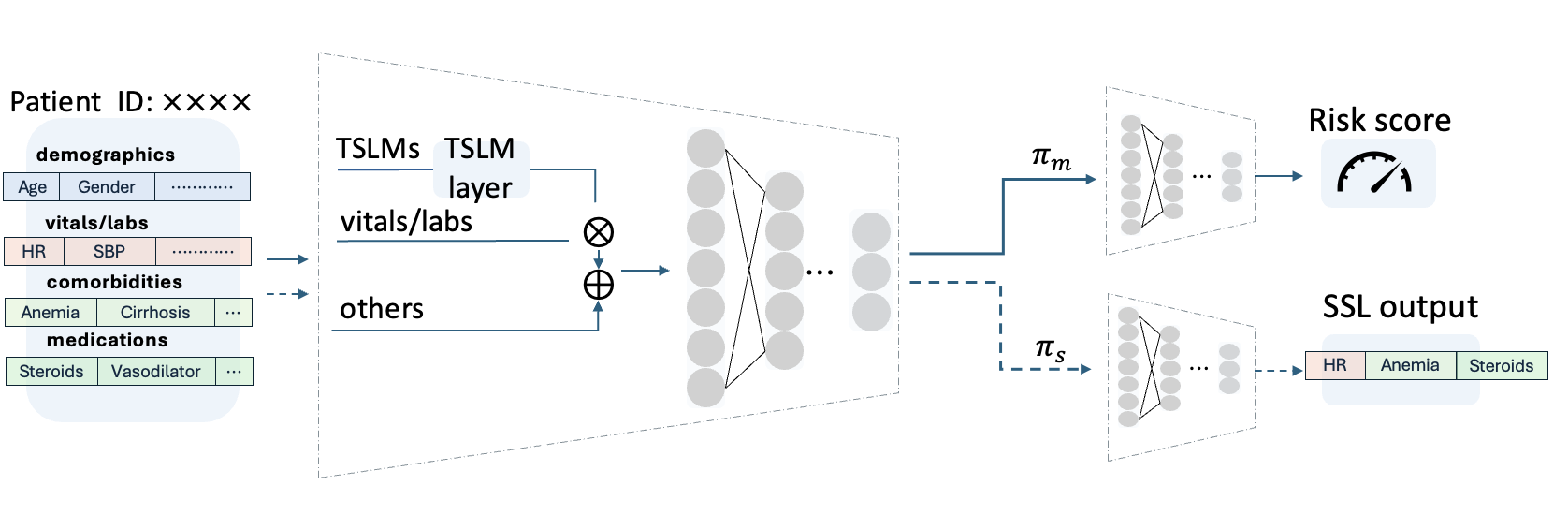

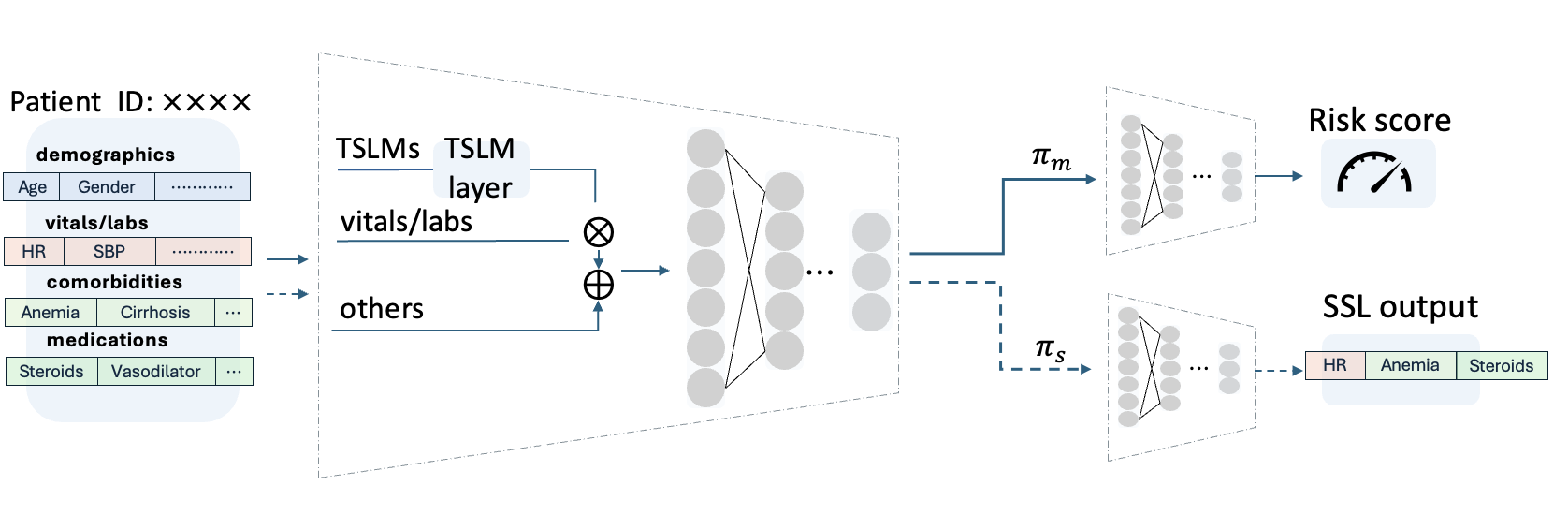

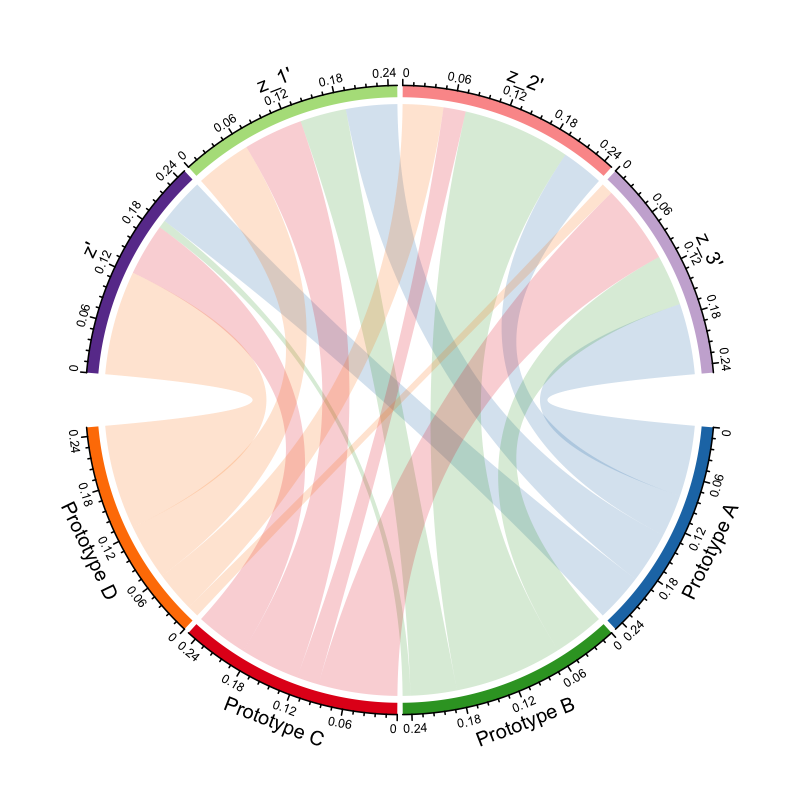

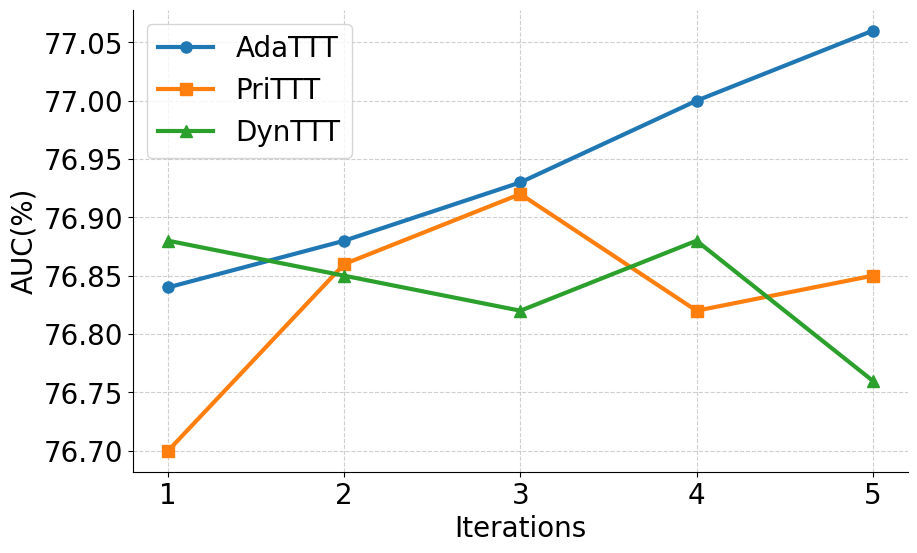

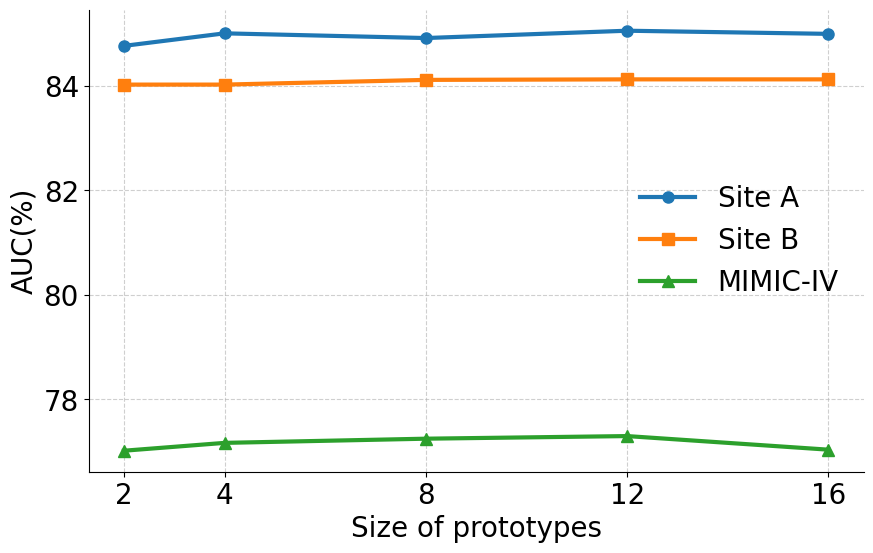

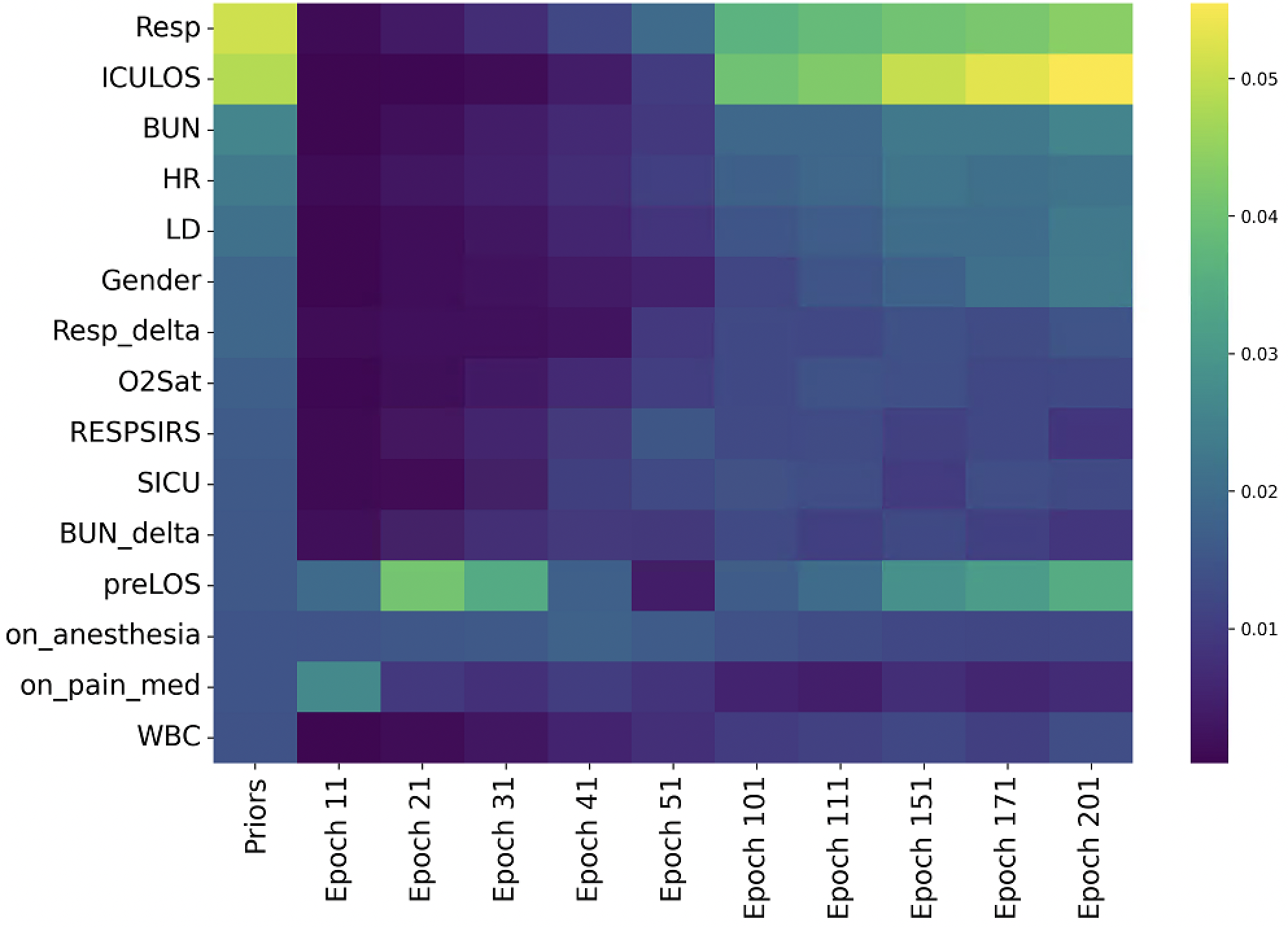

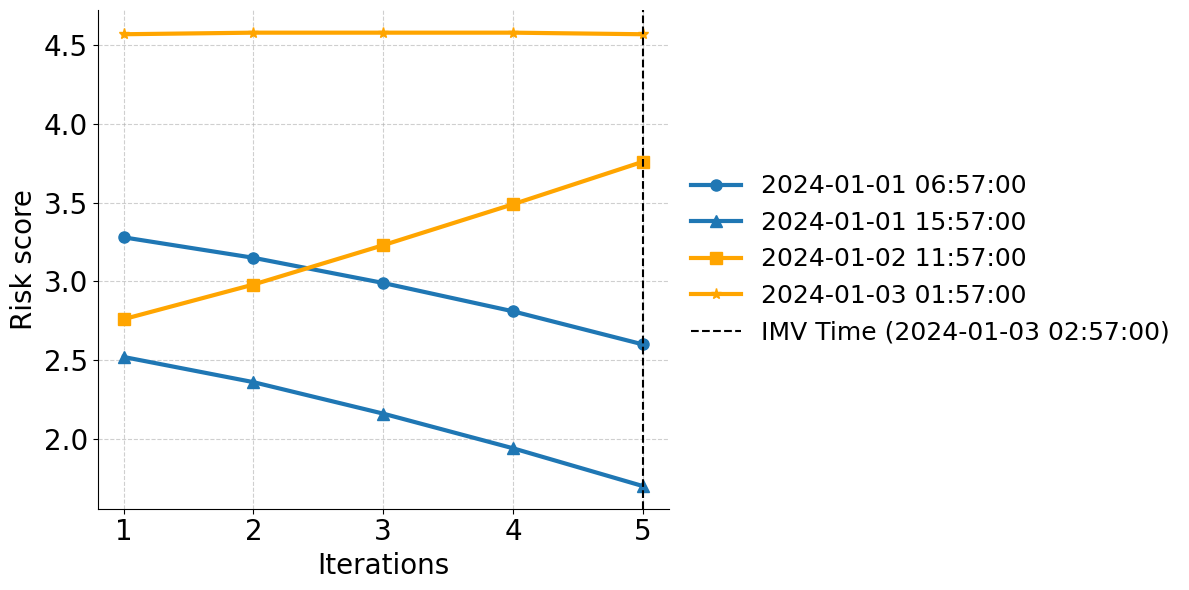

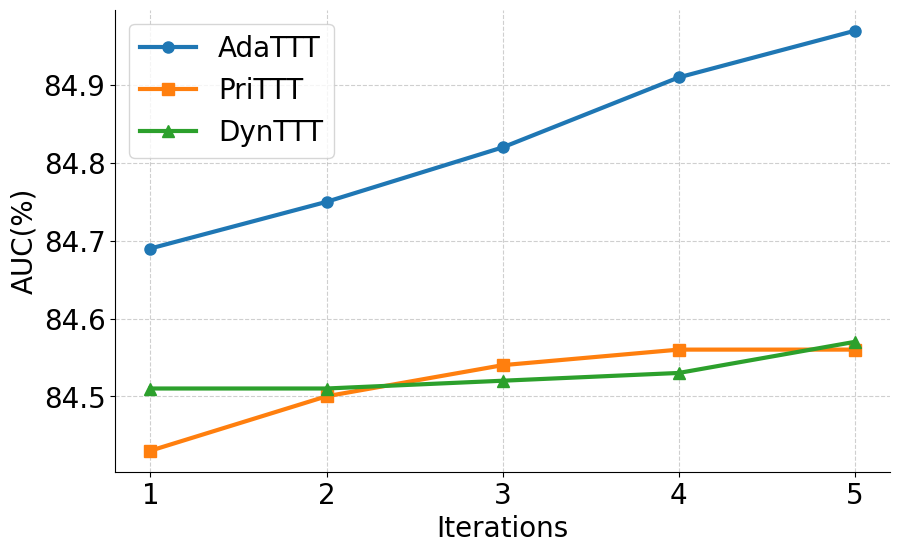

Accurate prediction of the need for invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) in intensive care units (ICUs) patients is crucial for timely interventions and resource allocation. However, variability in patient populations, clinical practices, and electronic health record (EHR) systems across institutions introduces domain shifts that degrade the generalization performance of predictive models during deployment. Test-Time Training (TTT) has emerged as a promising approach to mitigate such shifts by adapting models dynamically during inference without requiring labeled target-domain data. In this work, we introduce Adaptive Test-Time Training (AdaTTT), an enhanced TTT framework tailored for EHR-based IMV prediction in ICU settings. We begin by deriving information-theoretic bounds on the test-time prediction error and demonstrate that it is constrained by the uncertainty between the main and auxiliary tasks. To enhance their alignment, we introduce a self-supervised learning framework with pretext tasks: reconstruction and masked feature modeling optimized through a dynamic masking strategy that emphasizes features critical to the main task. Additionally, to improve robustness against domain shifts, we incorporate prototype learning and employ Partial Optimal Transport (POT) for flexible, partial feature alignment while maintaining clinically meaningful patient representations. Experiments across multi-center ICU cohorts demonstrate competitive classification performance on different test-time adaptation benchmarks.

Invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) is a critical intervention utilized in intensive care units (ICUs) for patients with severe respiratory failure and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) Grotberg et al. [2023]. However, its use is complicated by the risk of ventilator-induced lung injury and complications resulting from prolonged IMV. Timely and accurate identification of patients at high risk for mechanical ventilation is crucial for optimizing clinical decision-making. Early recognition of these patients enables proactive medical interventions and facilitates efficient resource allocation within hospital system [Fan et al., 2018].

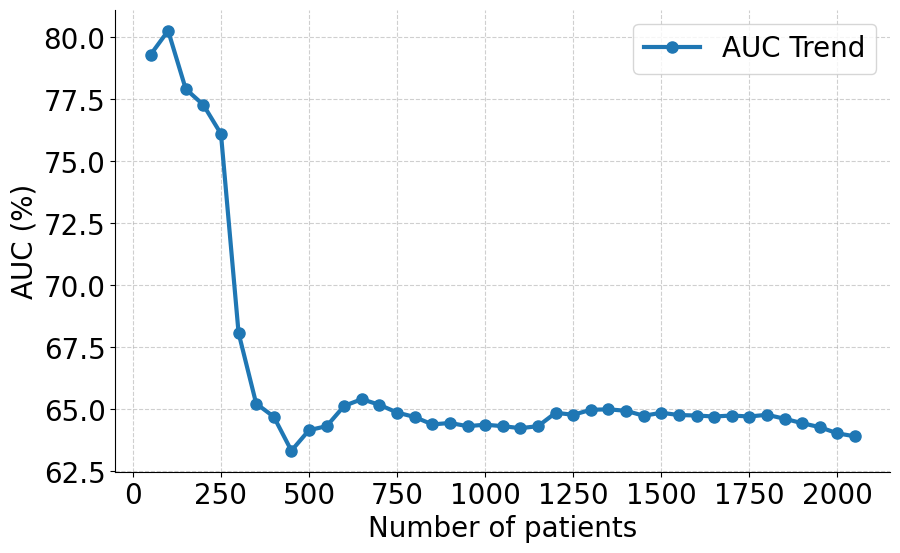

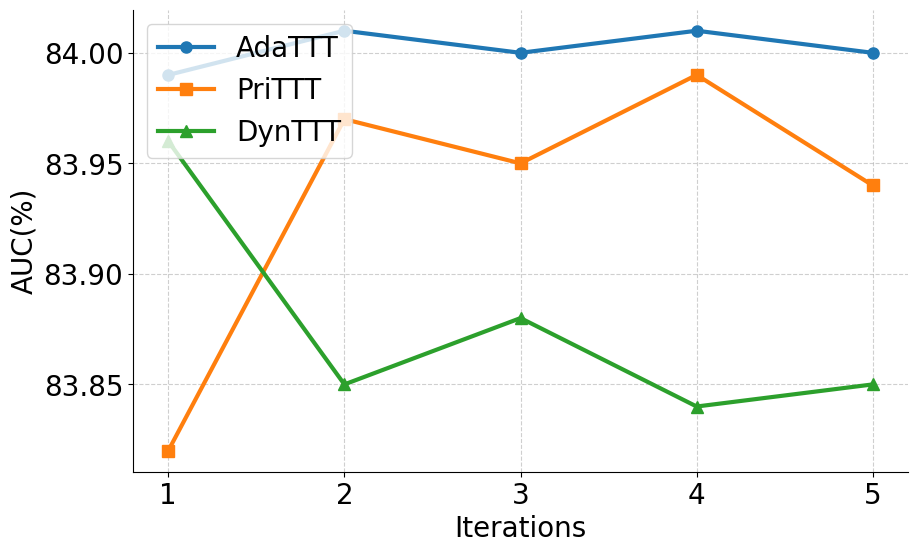

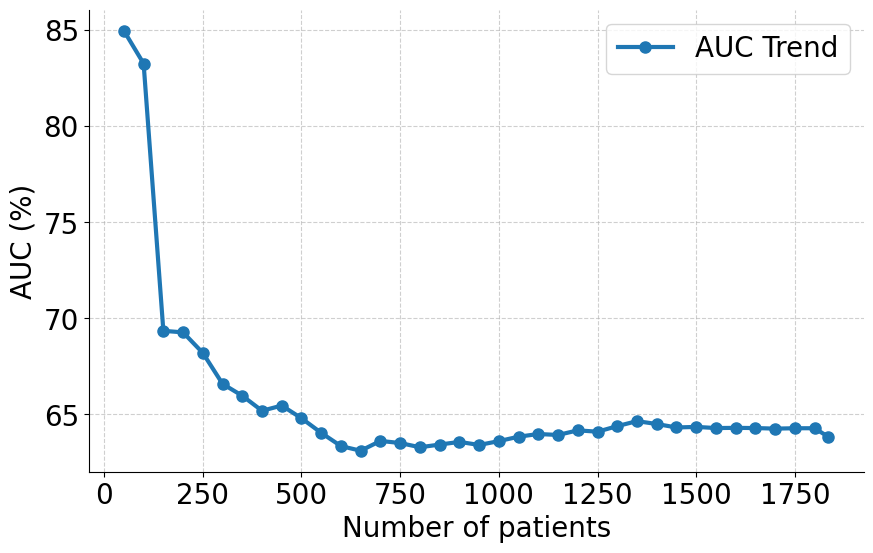

In recent years, the development of machine learning (ML) models has shown great promise in predicting the need for IMV, which leverages electronic health record (EHR) data to identify complex patterns that human clinicians might overlook [Shashikumar et al., 2021a]. These models can incorporate diverse features, including vital signs and laboratory results to enhance prediction accuracy and provide critical decision support in ICU settings. However, the effective deployment of such models in real-world clinical settings remains a challenge. A key issue is the variability in data distributions across hospitals due to differences in patient populations, clinical practices, and EHR systems. These shifts, often referred to as domain shifts, can substantially degrade the performance of predictive models that were trained on data from a single or limited number of sources. For instance, a respiratory failure prediction model [Lam et al., 2024] trained on ICU cohort from UC San Diego Health showed an approximately 12% drop in the area under the curve (AUC) when evaluated on an external ICU cohort.

Addressing this challenge requires adaptive methodologies that can account for site-specific heterogeneity. Existing approaches include pre-training models on large multi-center datasets [Shashikumar et al., 2021a], and transfer learning to fine-tune models on site-specific data [Lam et al., 2024] to align feature representations across domains. While these methods have shown promise, many require access to labeled data from the target domain during training or involve 2 Related Work

Early IMV-risk tools such as ROX and regression scores are interpretable but struggle with nonlinear, time-varying physiology [Roca et al., 2019]. Leveraging EHR-scale data, VentNet predicts IMV 24h ahead with a feedforward model [Shashikumar et al., 2021a]; encoder-decoder designs like DBNet integrate structured signals and demographics [Zhang et al., 2021]; and multimodal hybrids that fuse CXR with EHR further boost discrimination [Tandon et al., 2023]. However, cross-site performance often degrades due to population, workflow, and EHR heterogeneity; recovery via target-domain fine-tuning is common but label-intensive and operationally impractical for continuous deployment.

TTA adapts models on unlabeled test inputs without revisiting source data [Liang et al., 2024]. Batch normalization(BN)centric methods include prediction-time BN statistics updates [Nado et al., 2020] and TENT’s entropy minimization for BN parameters [Wang et al., 2020], while source-free SHOT freezes the classifier and adapts the encoder with pseudo-labels [Liang et al., 2020]. Test-time training (TTT) attaches auxiliary SSL branches for online encoder updates [Sun et al., 2020]; extensions like TTT++ (contrastive) and ClusT3 (clustering) improve alignment but may inherit instability or assume domain consistency [Liu et al., 2021, Hakim et al., 2023].

Three relevant directions are: (i) T3A, an optimization-free method forming class prototypes from streaming test data to reweight logits that is efficient but classifier-level only, assuming stable class structure [Iwasawa and Matsuo, 2021]; (ii) SAR, which filters unreliable samples and applies sharpness-aware entropy minimization for stable BN updates that is effective with small batches yet BN-dependent [Niu et al., 2023]; (iii) CoTTA, maintaining a moving teacher with augmentation-and weight-averaged pseudo-labels plus periodic restoration, is useful for long horizons but hyperparameter-sensitive with potential error accumulation [Wang et al., 2022].

In EHR-driven IMV prediction, these approaches face practical challenges: tiny per-encounter batches undermine BN estimates; pseudo-labeling struggles with class imbalance and temporal nonstationarity; clustering assumptions break under irregular sampling and missingness; classifier-only adaptation cannot address representation shift, making direct application from vision to ICU EHRs difficult. (1)

At inference time, rather than relying on static model parameters, TTT dynamically adapts the encoder for each test instance x ′ by optimizing the SSL objective with

The adapted encoder is then used to obtain the final prediction with ŷ = h c (f e (x ′ ; θ e (x ′ )); θ * c ).

(3)

Prior work [Liu et al., 2021] derives accuracy bo

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.