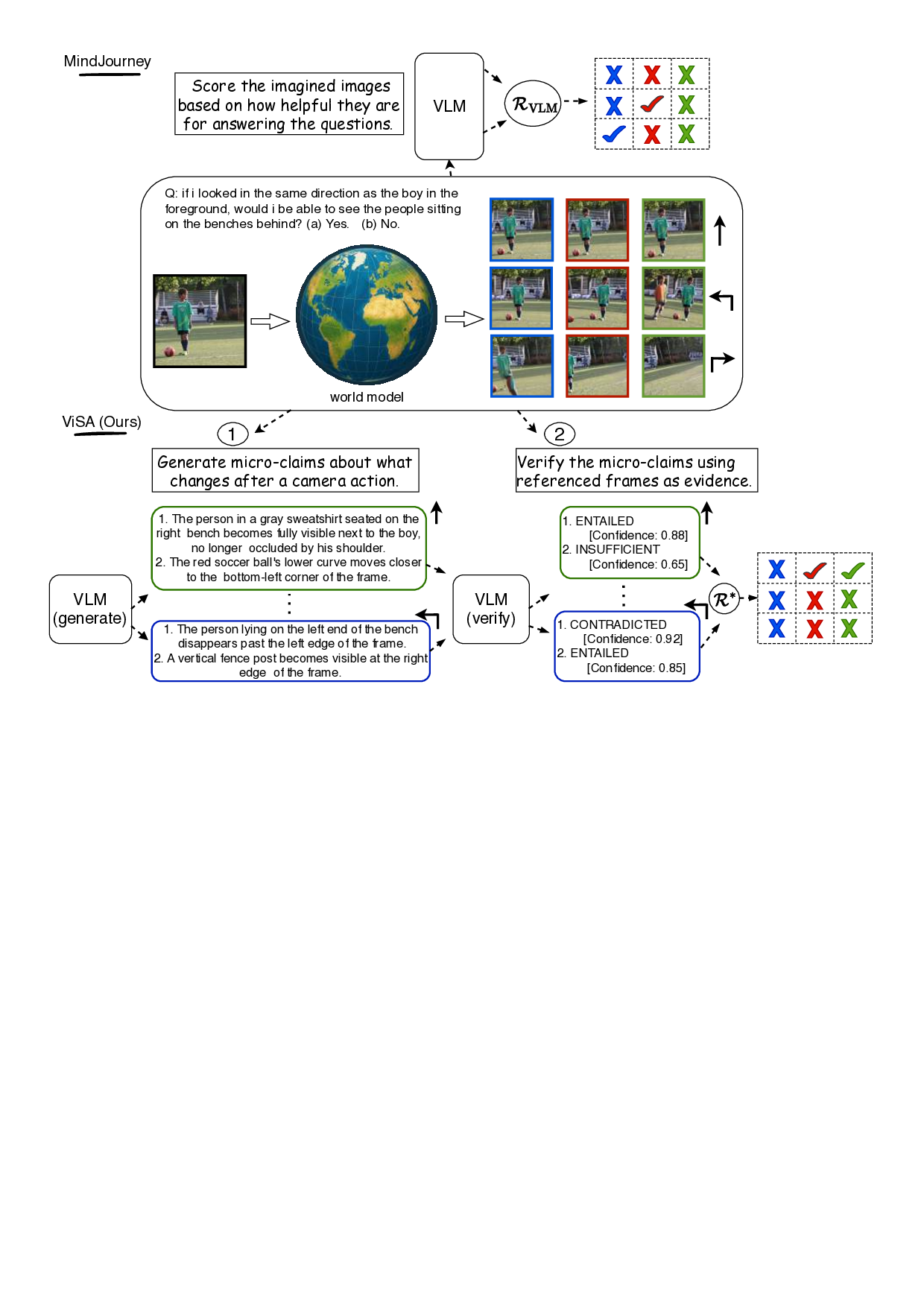

Vision-Language Models (VLMs) remain limited in spatial reasoning tasks that require multi-view understanding and embodied perspective shifts. Recent approaches such as MindJourney attempt to mitigate this gap through test-time scaling where a world model imagines action-conditioned trajectories and a heuristic verifier selects helpful views from such trajectories. In this work, we systematically examine how such test-time verifiers behave across benchmarks, uncovering both their promise and their pitfalls. Our uncertainty-based analyses show that MindJourney's verifier provides little meaningful calibration, and that random scoring often reduces answer entropy equally well, thus exposing systematic action biases and unreliable reward signals. To mitigate these, we introduce a Verification through Spatial Assertions (ViSA) framework that grounds the test-time reward in verifiable, frame-anchored micro-claims. This principled verifier consistently improves spatial reasoning on the SAT-Real benchmark and corrects trajectory-selection biases through more balanced exploratory behavior. However, on the challenging MMSI-Bench, none of the verifiers, including ours, achieve consistent scaling, suggesting that the current world models form an information bottleneck where imagined views fail to enrich fine-grained reasoning. Together, these findings chart the bad, good, and ugly aspects of test-time verification for world-model-based reasoning. Our code is available at https://github.com/chandar-lab/visa-for-mindjourney.

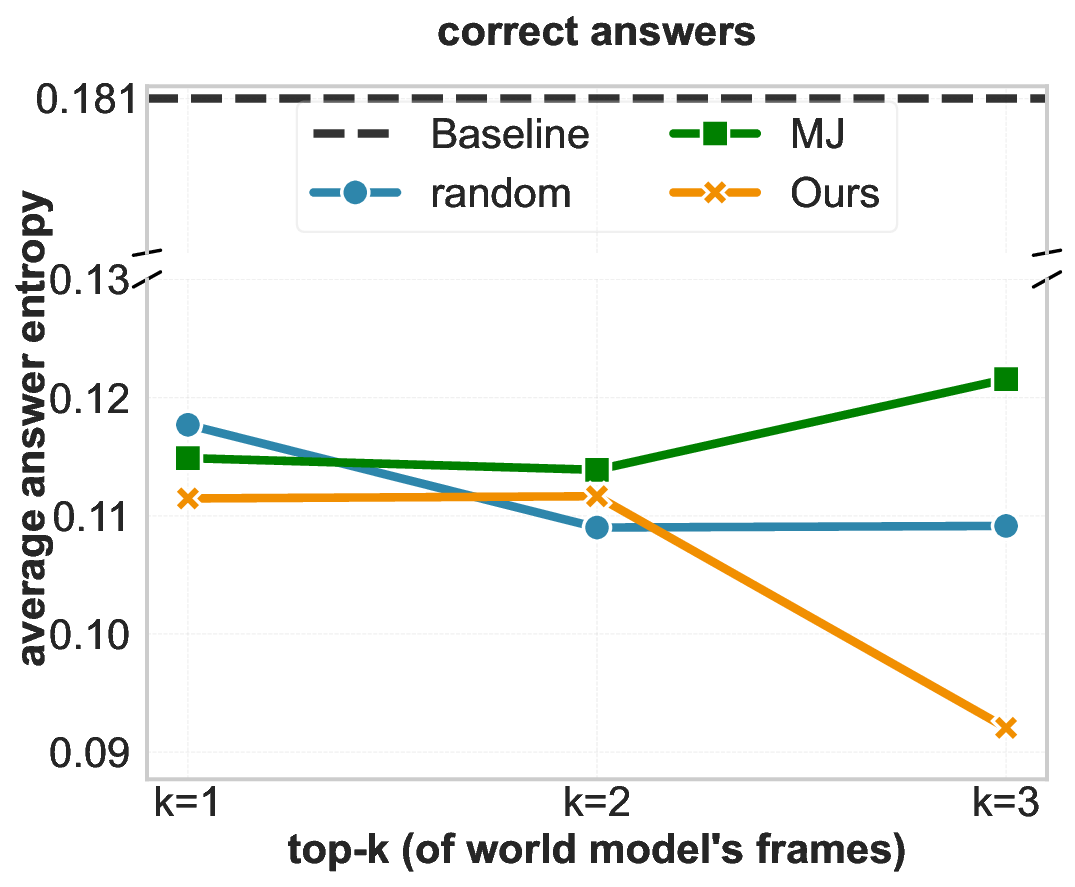

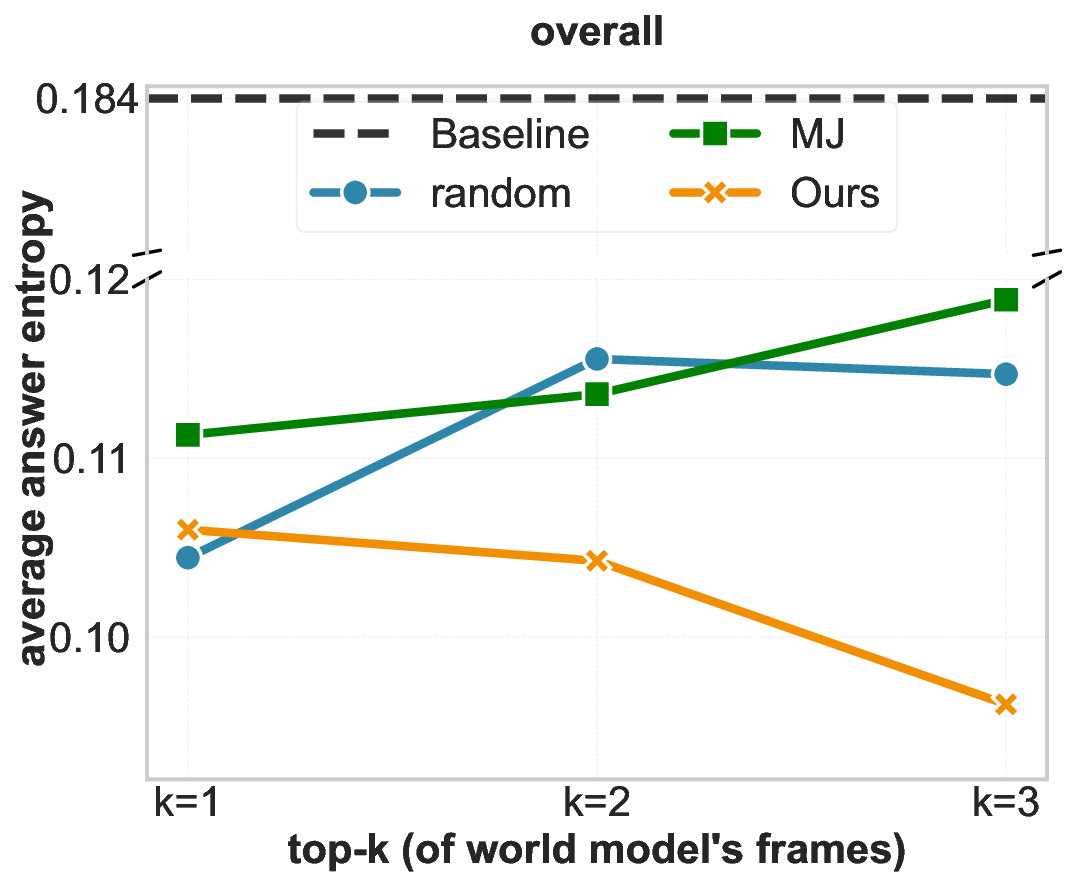

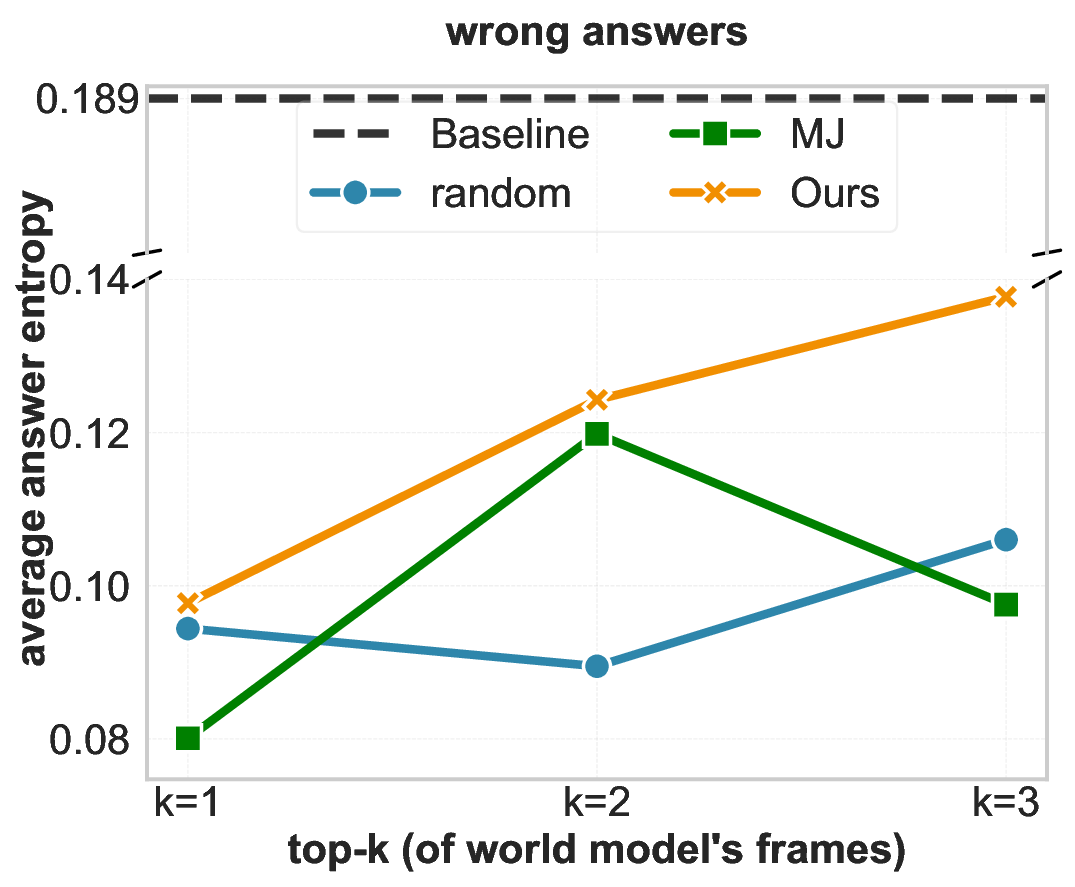

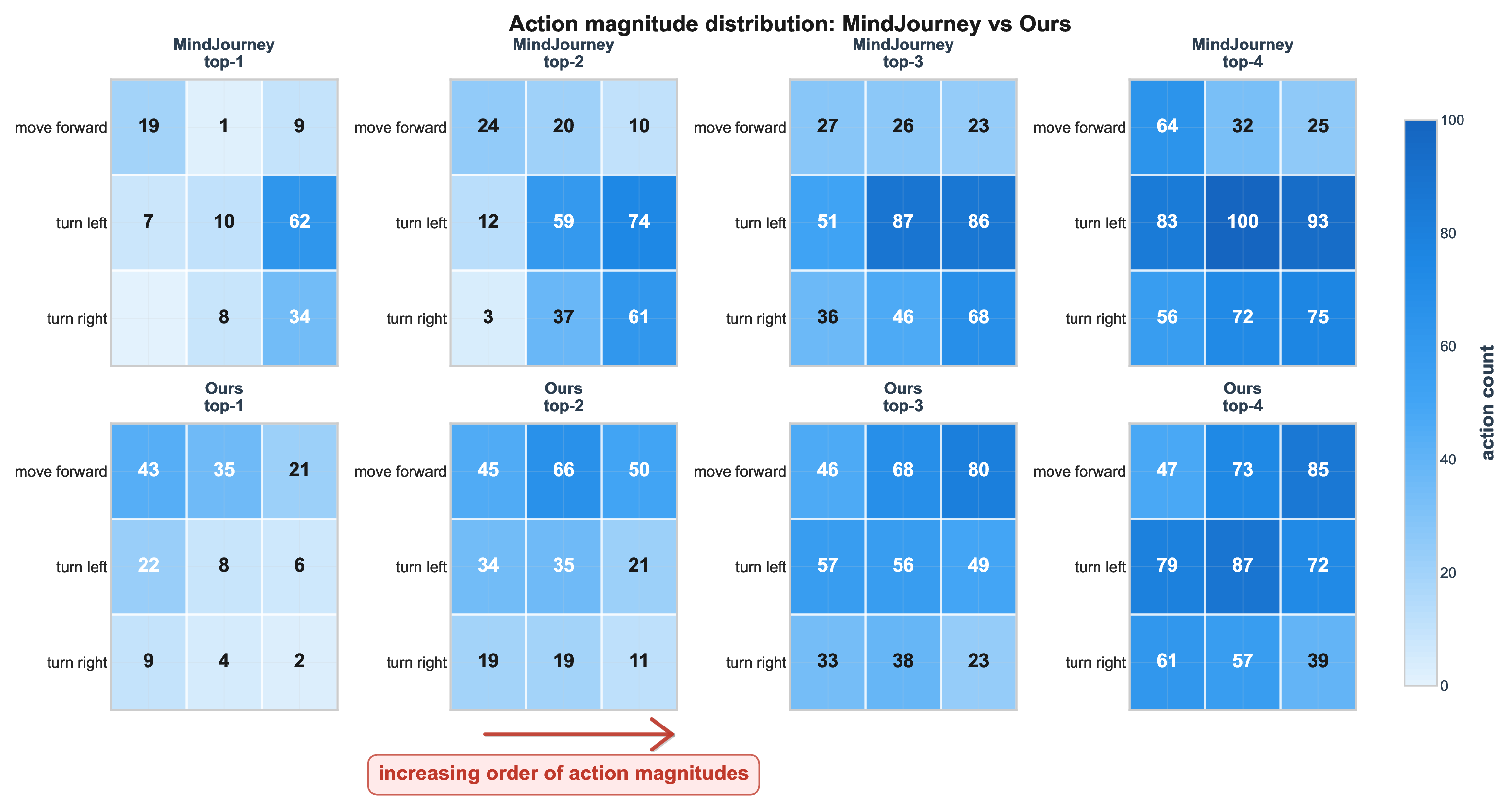

Spatial reasoning-the ability to infer 3D structure, object relations, and transformations across viewpoints-remains a persistent gap in Vision-Language Models (VLMs) (Yang et al., 2025a;Wang et al., 2024;Chen et al., 2025). MindJourney (MJ) (Yang et al., 2025c) attempts to close this gap through test-time scaling with world models, where imagined trajectories over actions are generated and scored by heuristic "helpfulness" verification. Yet, the faithfulness of such verifier remains unclear. We begin by probing how much does MJ's verifier effect the answer selection confidence of a VLM to examine whether it genuinely helps with spatial reasoning. Entropy-based ablations reveal that its scoring mechanism barely reduces uncertainty compared to random selection, often reinforcing systematic biases in action selection. These findings expose a lack of calibration in heuristic verifiers that naively exploit the design of existing VLMs in considering only the global image context for reasoning (Cheng et al., 2024).

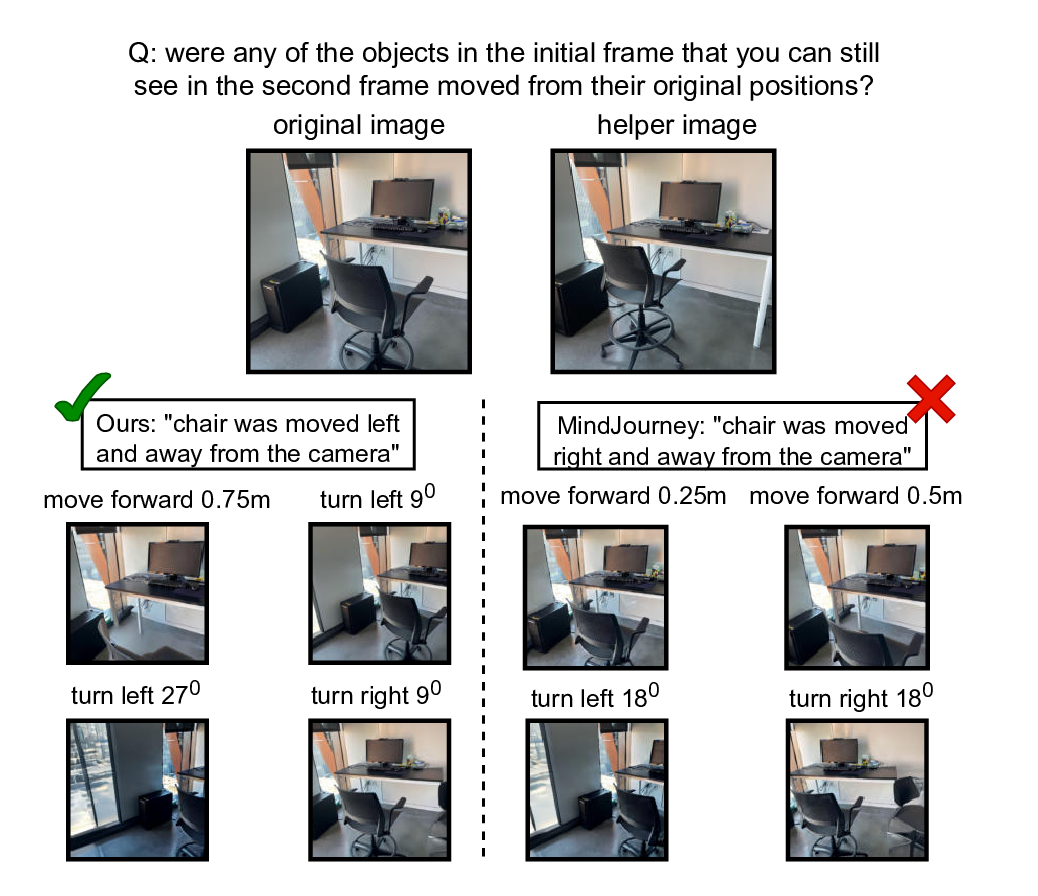

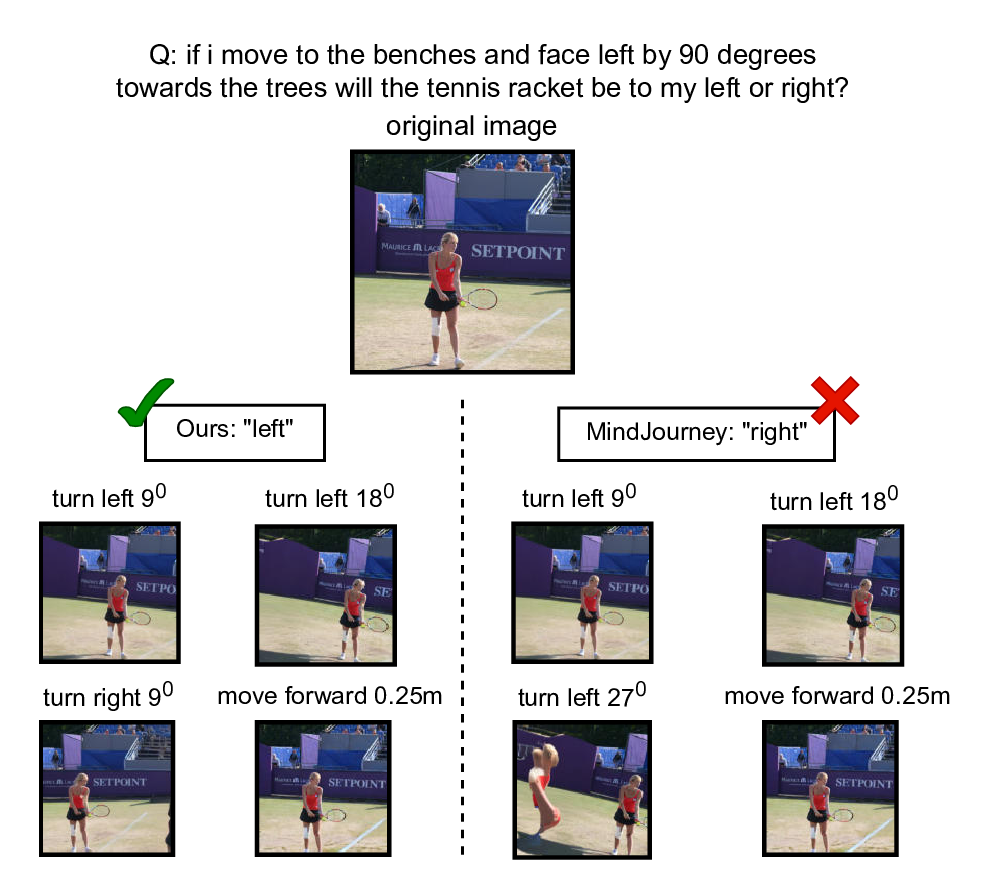

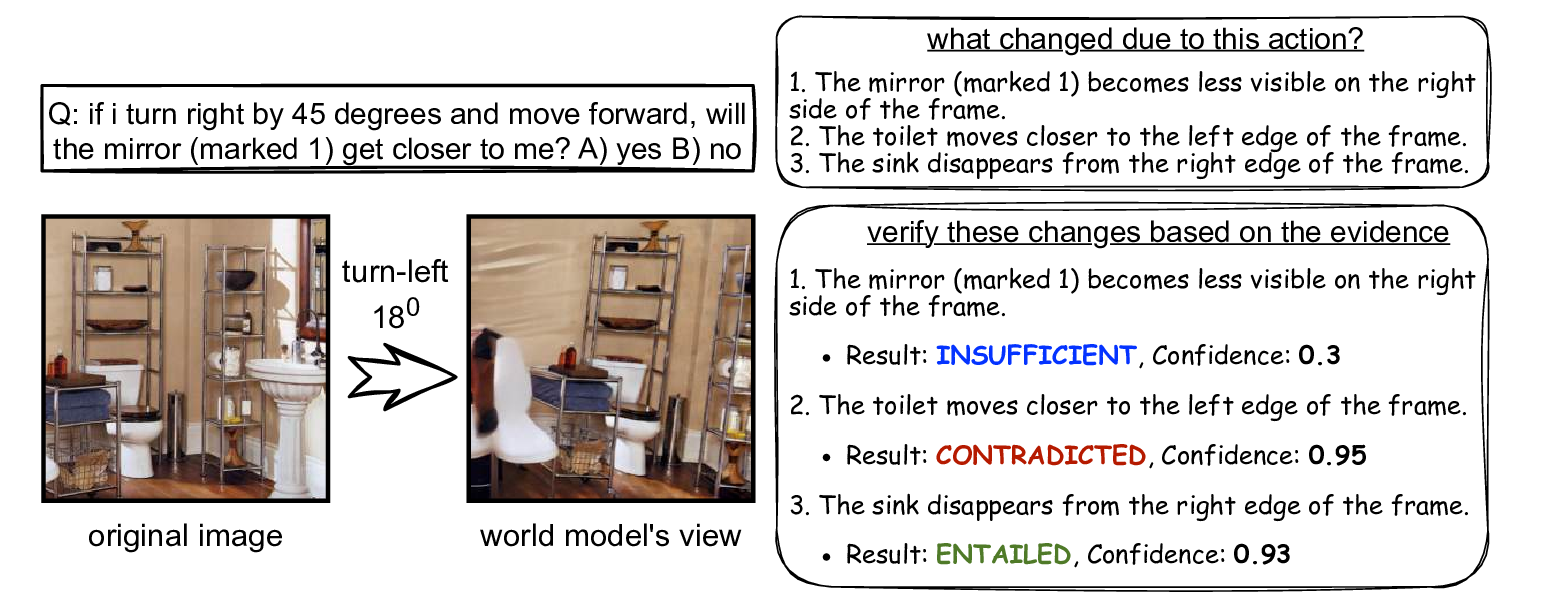

To address these shortcomings, we look at test-time verification through the lens of proposer-solver paradigm, which has recently been traction due to its ability to help VLMs generate their own diverse and challenging reward signals while reducing their reliance on costly verification (Thawakar et al., 2025;He et al., 2025). Namely, we introduce Verification through Spatial Assertion (ViSA), a claim-based assertion framework that grounds trajectory evaluation in explicit, frame-level regional information for reasoning (see fig. 2). Instead of relying on black-box scalar rewards, ViSA prompts the model to propose micro-claims describing spatial relations observed in imagined frames, and evaluates them for consistency and informativeness. Based on the evaluations, each imagined view from the world model is assigned an evidence quality (EQ) score as a principled test-time reward that reflects the frame’s relevance to the question alongside the verifier VLM’s overall confidence in its evaluations. In contrast to prior proposer-solver methods, which are used almost exclusively for training-time self-improvement (Zhao et al., 2025), ViSA is the first such technique to apply a proposer-solver interaction at test time for compute scaling in spatial reasoning tasks for VLMs.

Our experiments show that ViSA achieves a significant performance gain on the SAT-Real benchmark (Ray et al., 2025) while yielding more balanced exploration behavior over MJ’s heuristic approach. However, when extended to MMSI-Bench (Yang et al., 2025b), which emphasizes fine-grained relational and attribute reasoning, all verifiers, including ours, plateau and fail to scale with additional imagined views. Ablating the perceptual quality scores of the generated views point to an underlying information bottleneck in using current world models for test-time scaling of VLMs: when simulated trajectories fail to introduce new or reliable spatial cues, verification alone cannot help. Together, these findings offer a nuanced view of test-time verification-clarifying when it works, why it fails, and what future world model-based approaches must overcome for robust spatial reasoning.

Let x 0 denote the initial input image depicting a 3D scene, and q represent a spatial reasoning question with answer choices A = {α 1 , . . . , α n }. Our goal is to predict the correct answer α * ∈ A. Traditional VLMs model this as P (α * |x 0 , q), but struggle with complex spatial reasoning requiring multi-viewpoint analysis.

Test-time verification of world models’ outputs: At inference-time, a pre-trained video-diffusion world model W acts as a markov decision process (Cong et al., 2025) when prompted with the reference image x 0 , a prompt c, and a trajectory τ = (f 1 , . . . , f t-1 ) comprising a sequence of frames f i to autoregressively generate an imagined video:

where V t is composed of m frames (x 1 , . . . , x m ) that can be readily used as helpful signals for a downstream task.

However, not all these imagined frames in V t are useful for the task’s performance. Hence, a test-time reward function R helps quantify the relevance of the generated frames for a given task (Cong et al., 2025).

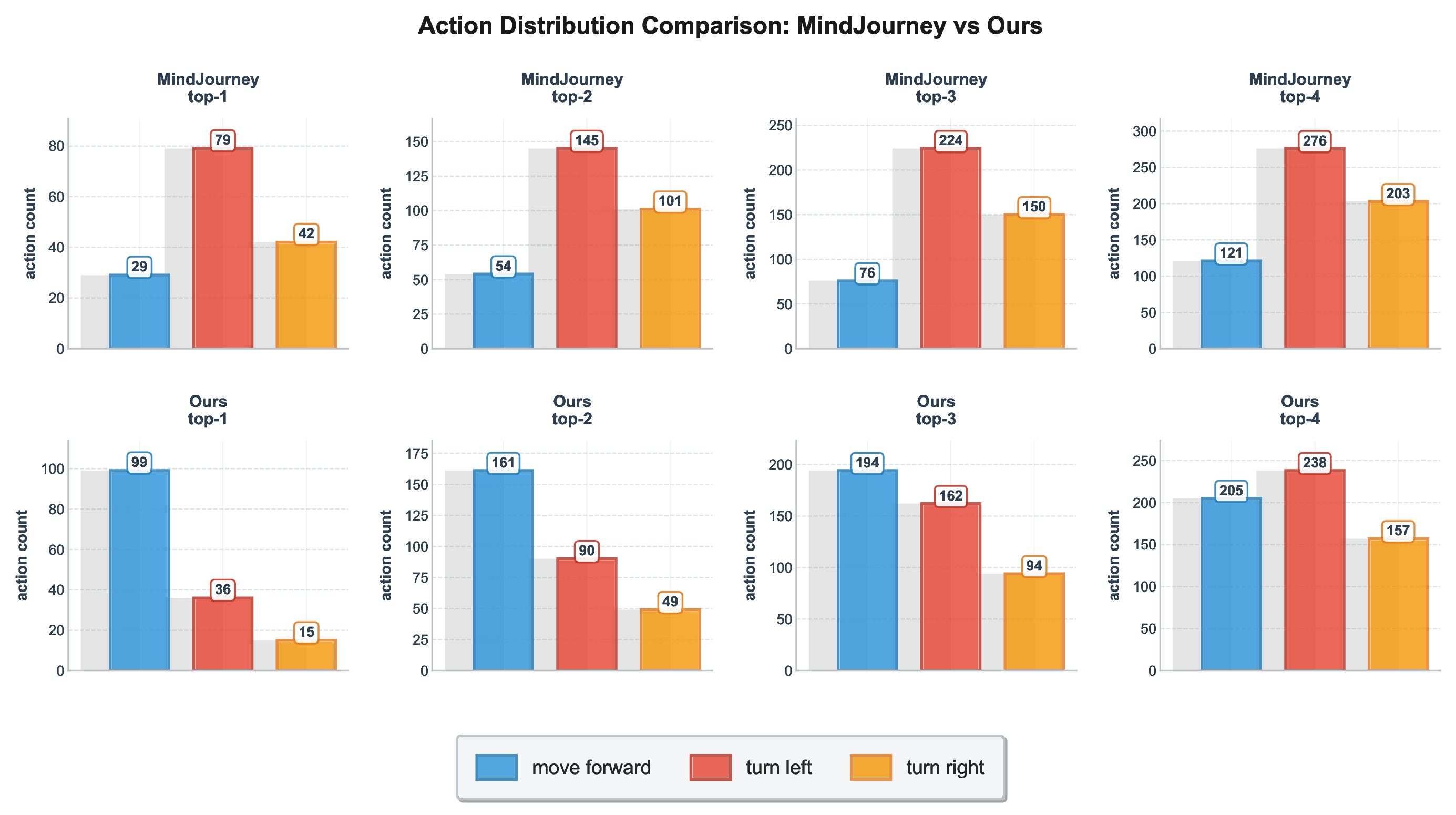

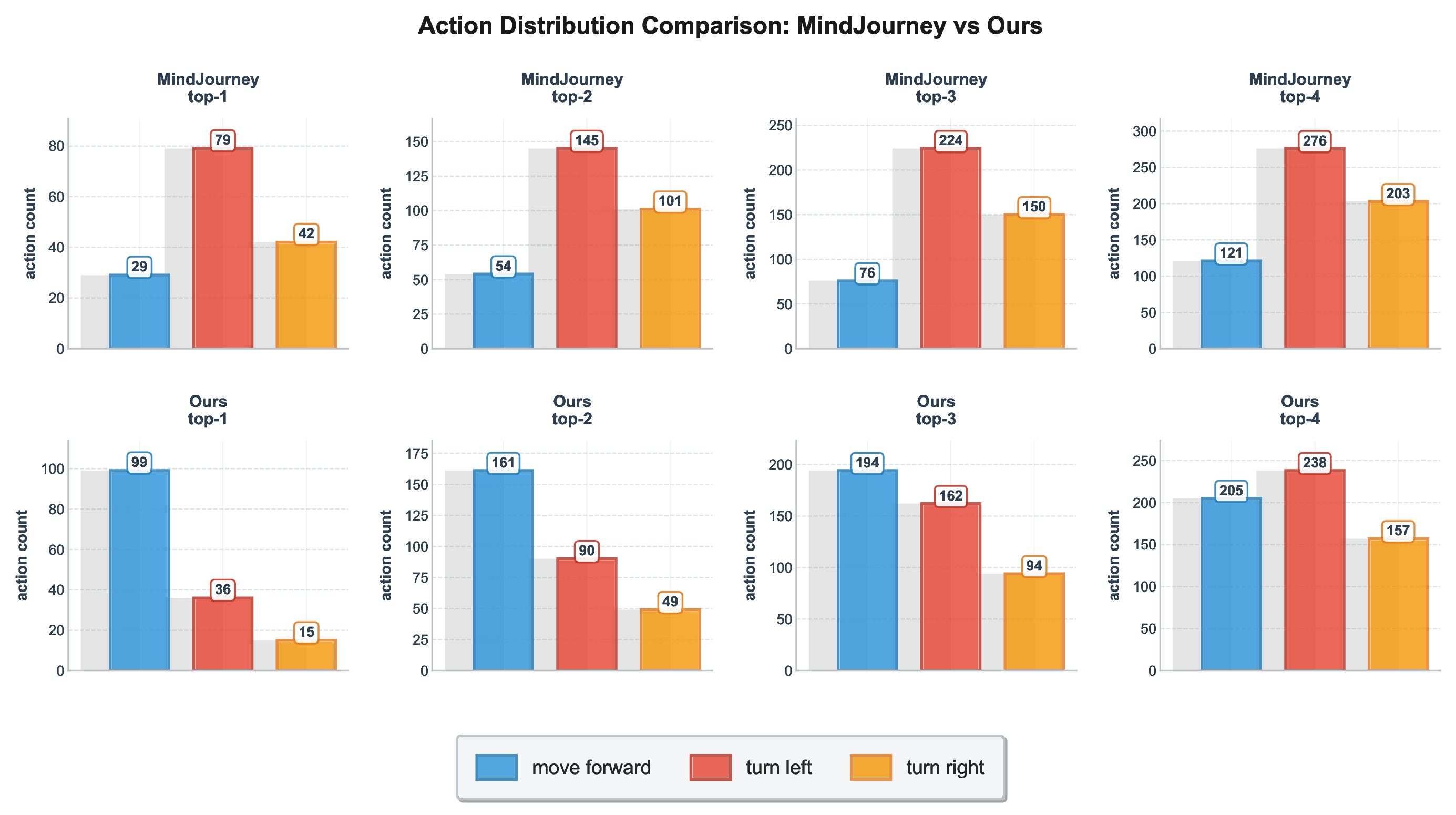

MindJourney’s heuristic test-time verification: MindJourney (MJ) (Yang et al., 2025c) employs the imagined frames of the world model as egocentric rollouts to address spatial reasoning through beam search, i.e., the output V t simulates how an embodied agent would navigate the static 3D scene referenced by the input image x 0 . For this, an action space of a small set of primitive actions a i is used, namely a i ∈ {move-forward d, turn-left θ l , turn-right θ r }, where d and (θ l , θ r ) are the actions’ magnitudes in meters and degrees, respectively. The frames f i comprising the trajectory input τ to the world model (equation 1) are effective mappings of the action a i by a camera-pose transformation: ψ(a i ) = f i ∈ SE(3). As its test-time reward function, MJ

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.