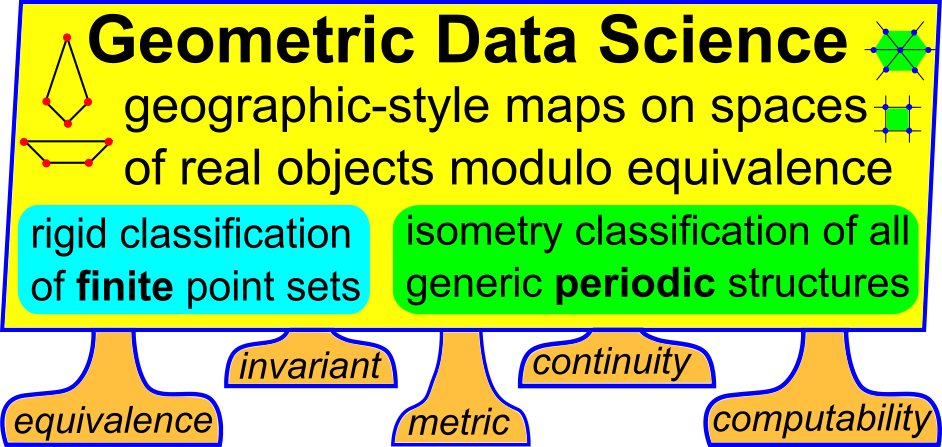

This book introduces the new research area of Geometric Data Science, where data can represent any real objects through geometric measurements.

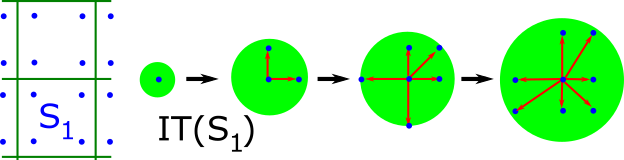

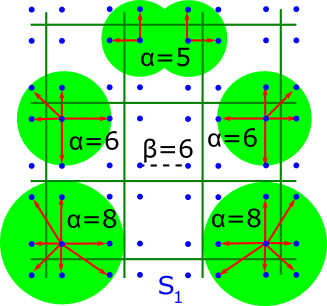

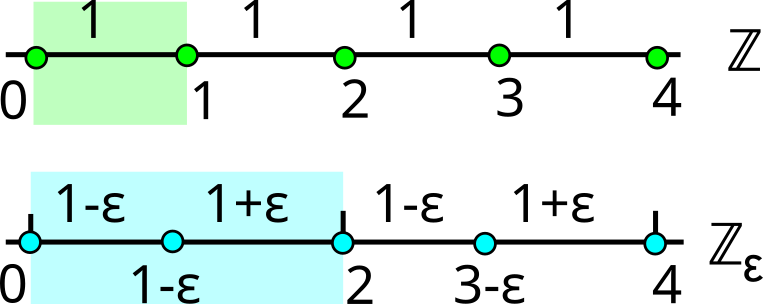

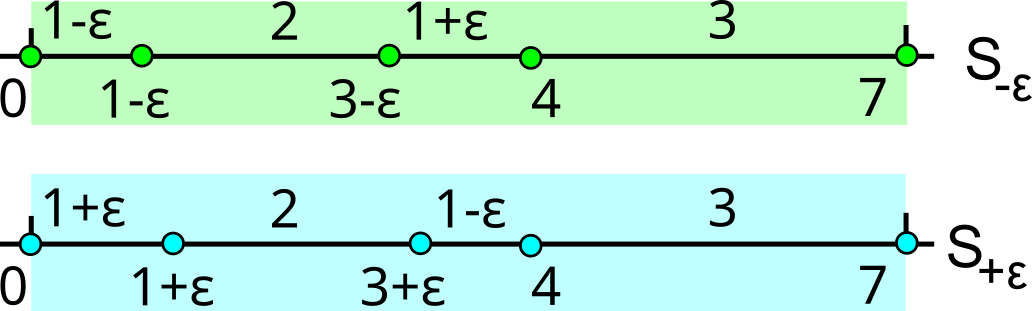

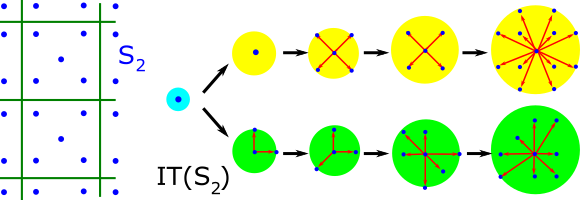

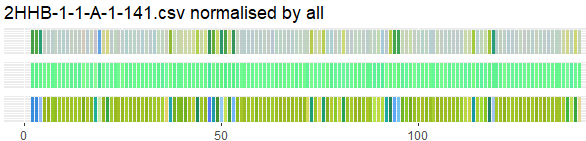

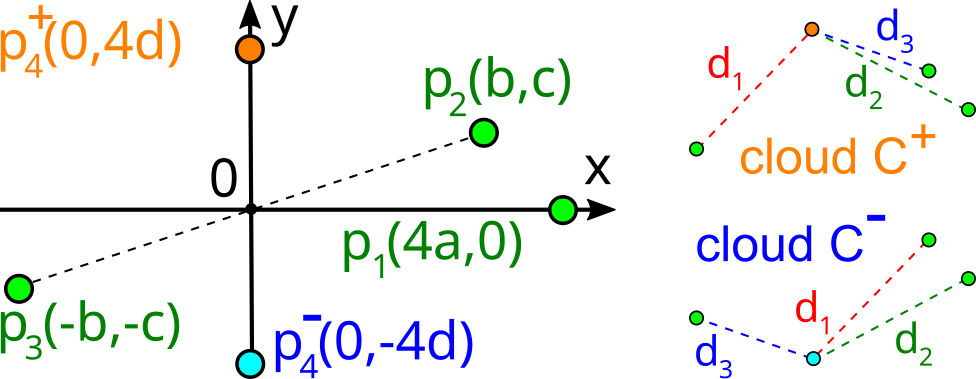

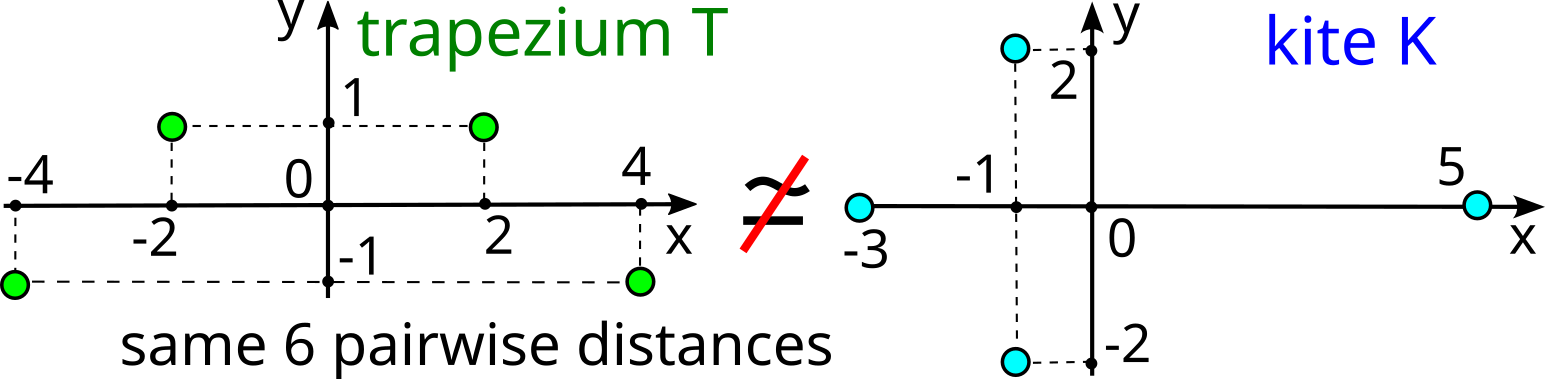

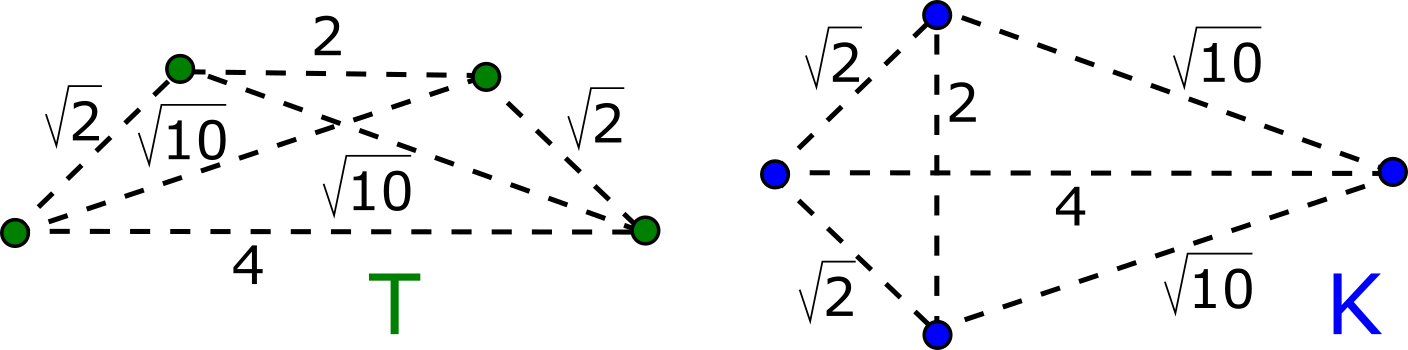

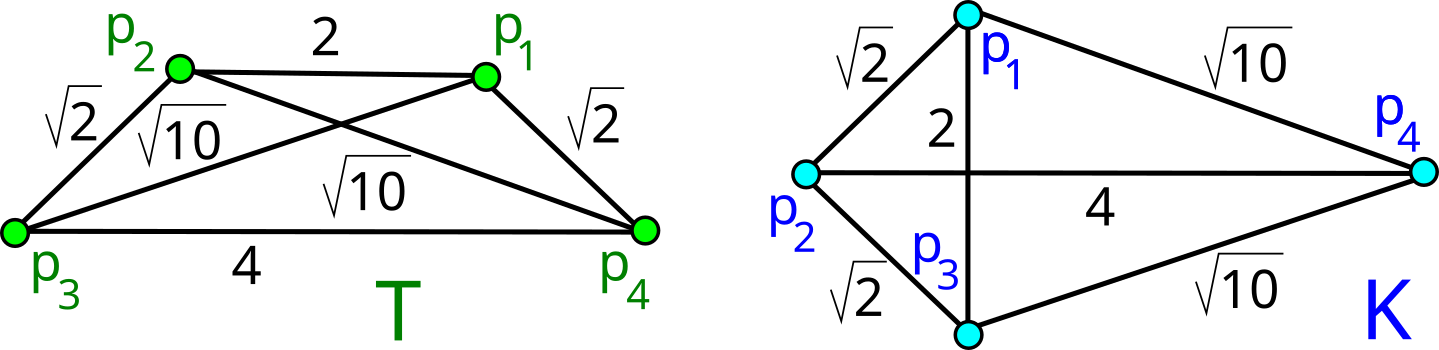

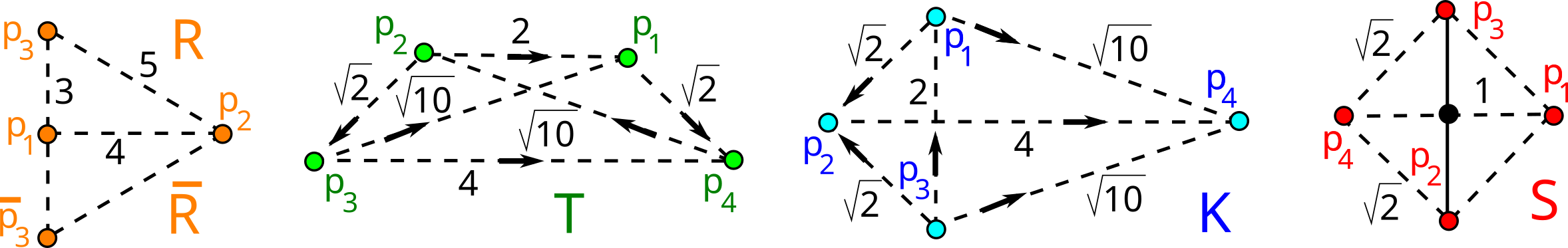

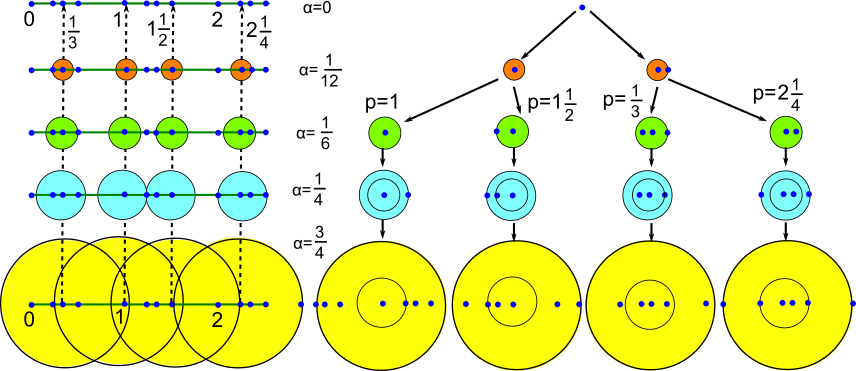

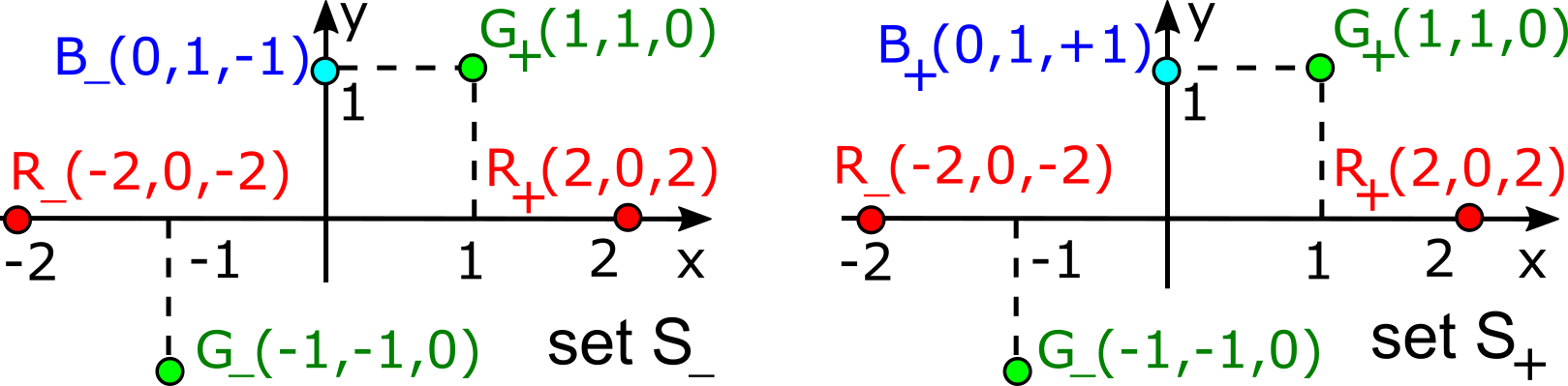

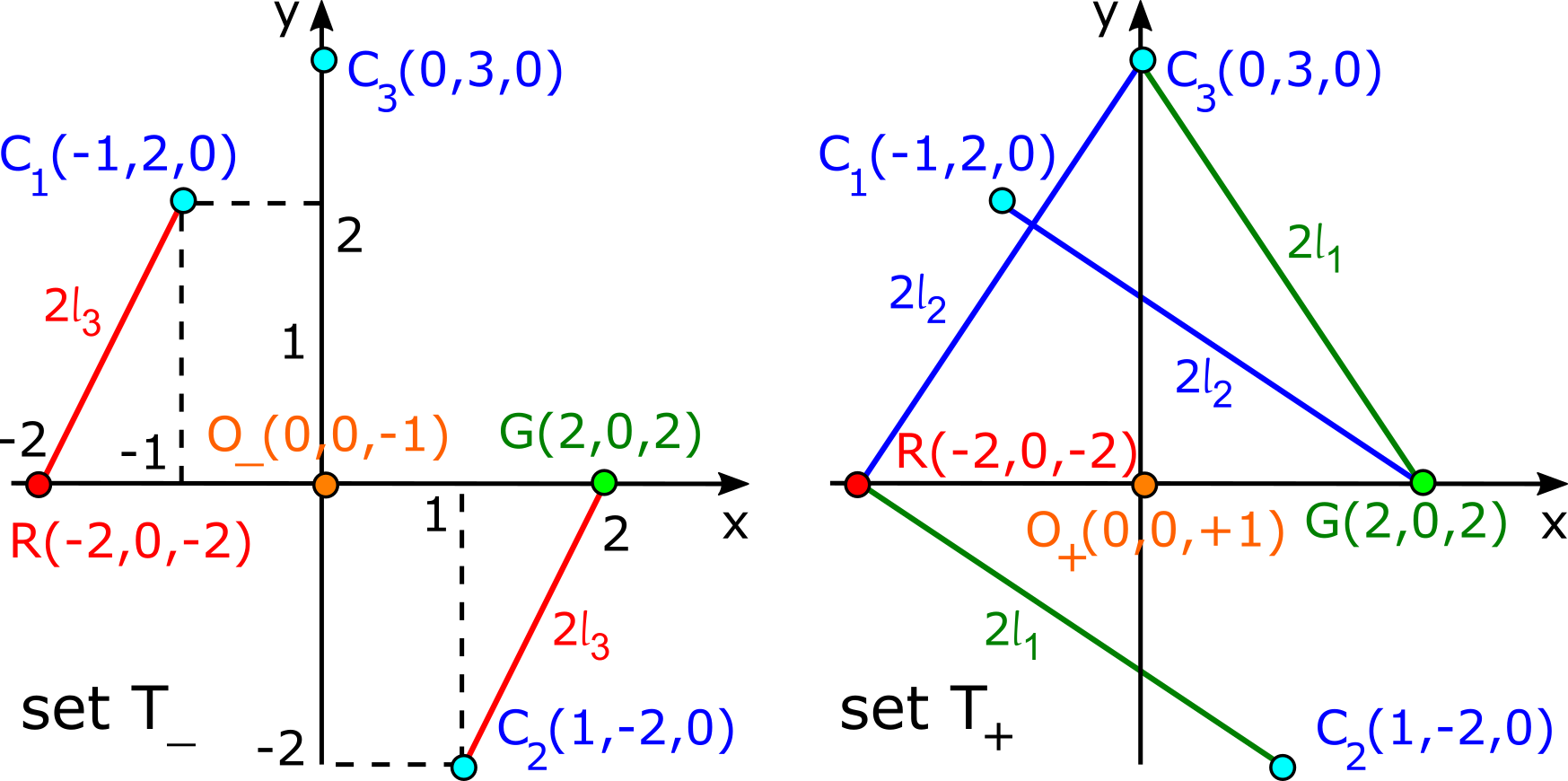

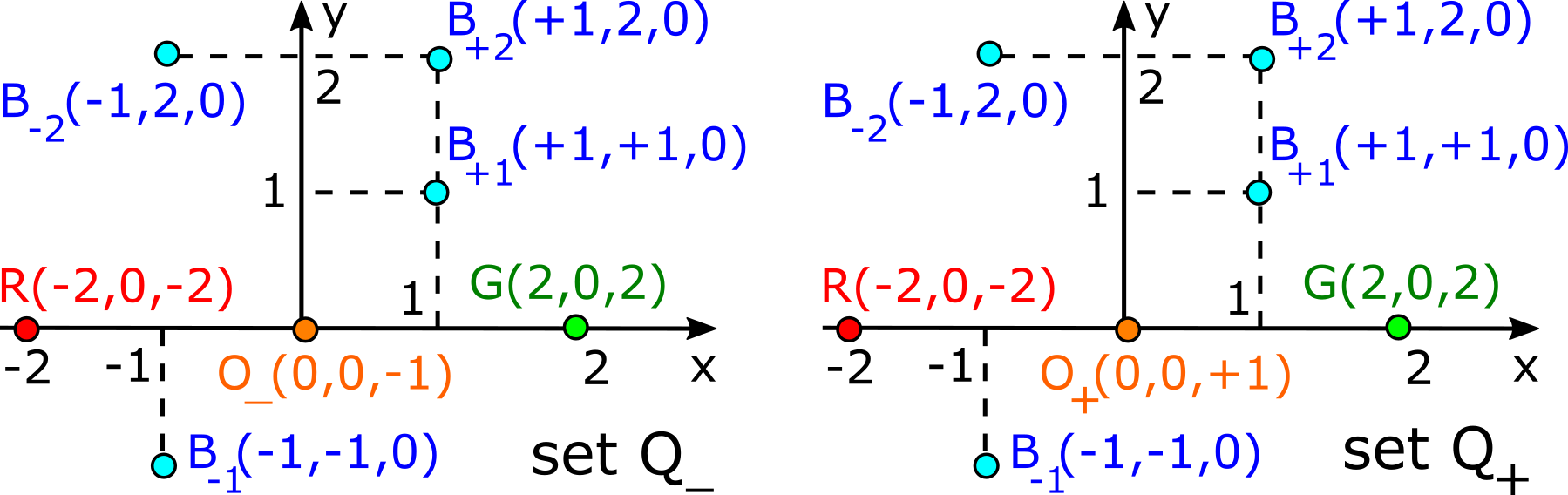

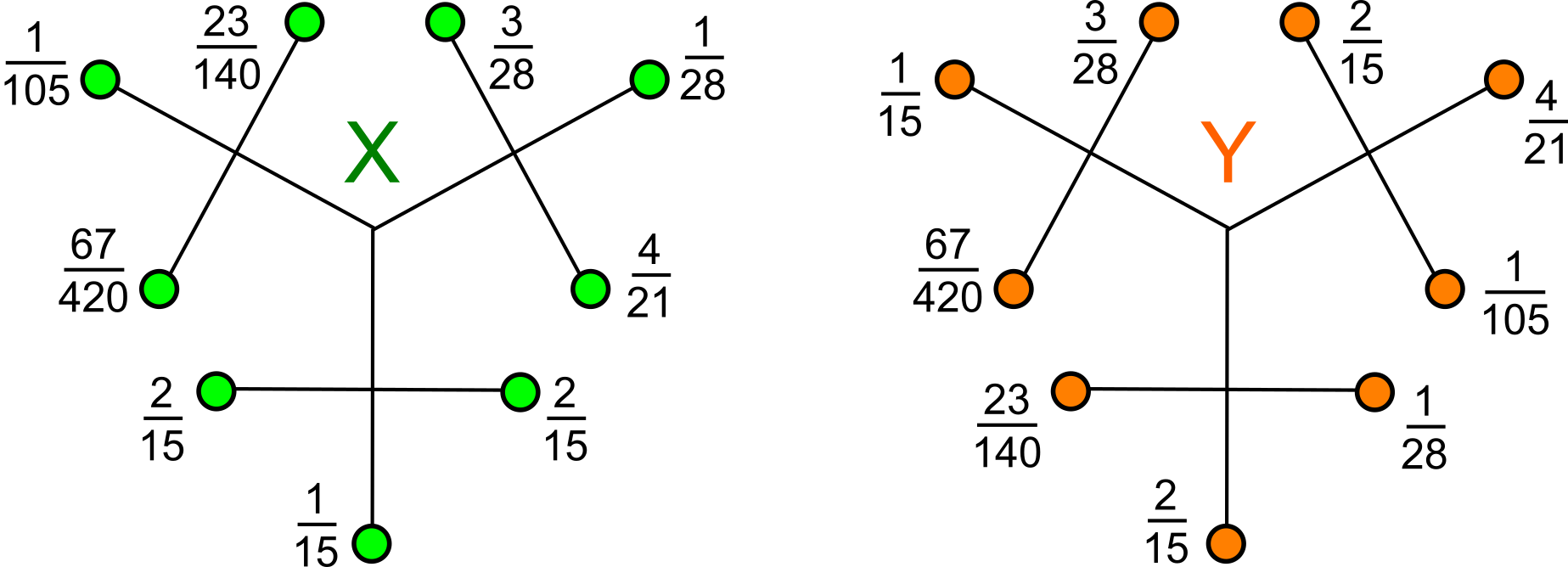

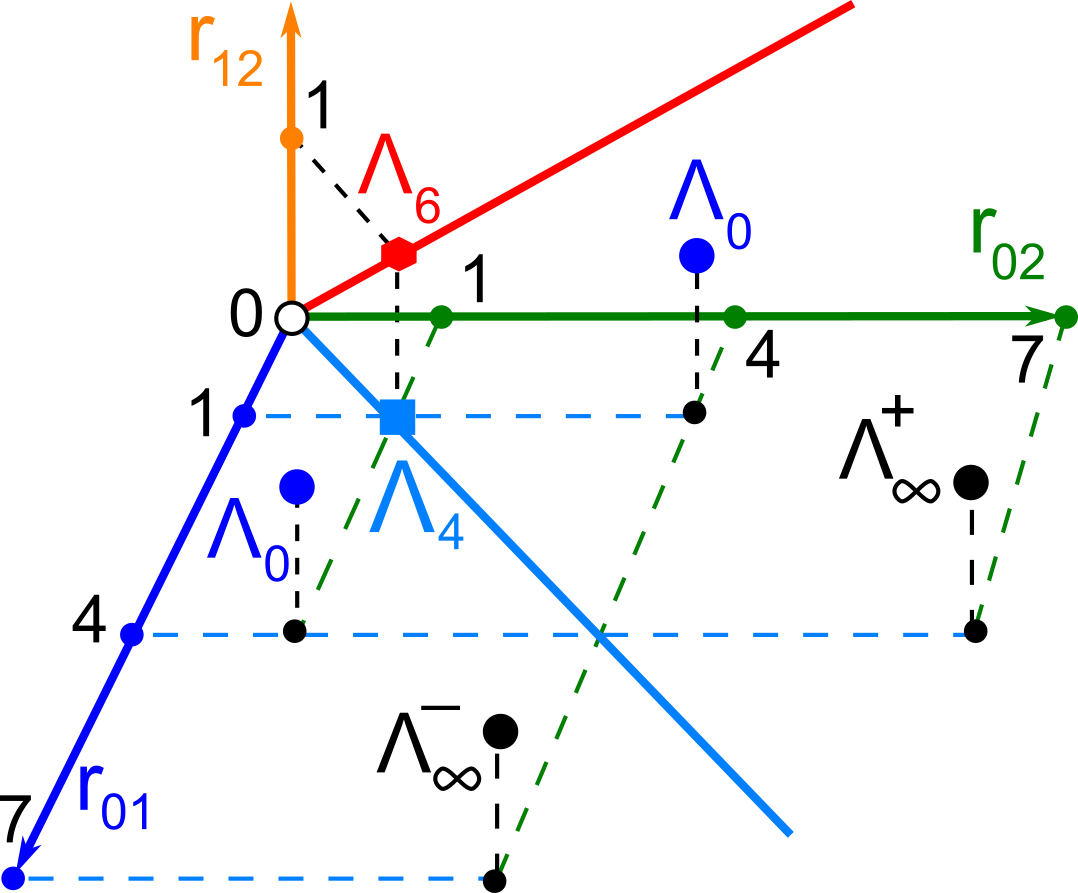

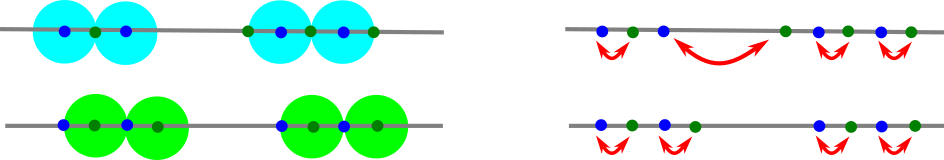

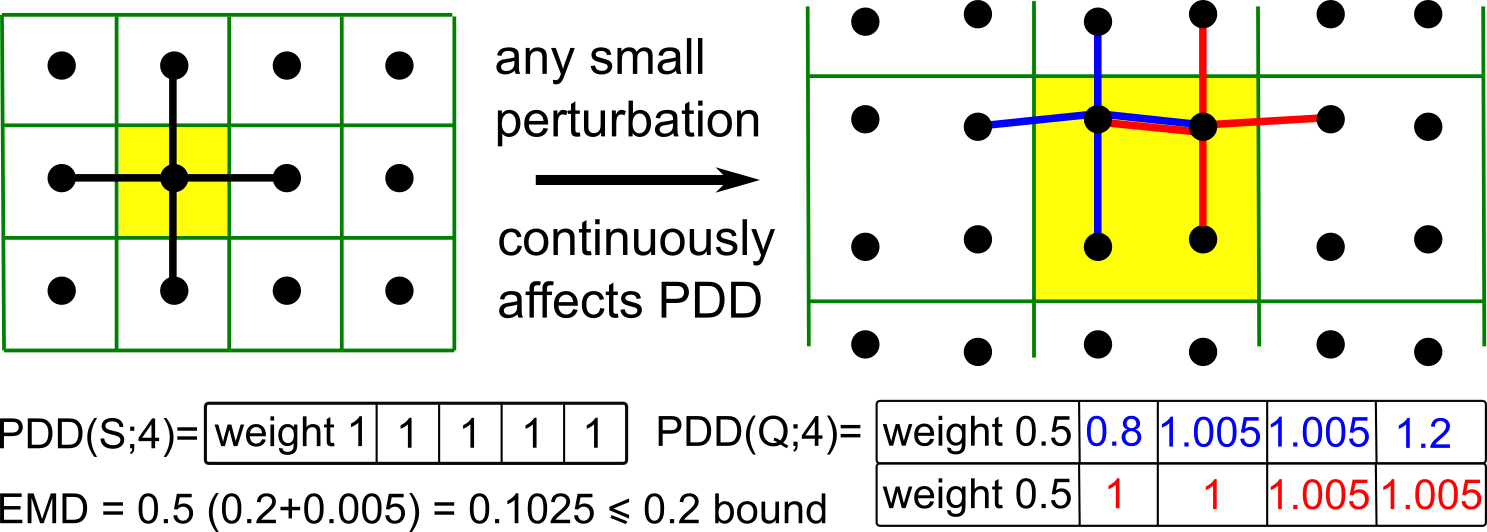

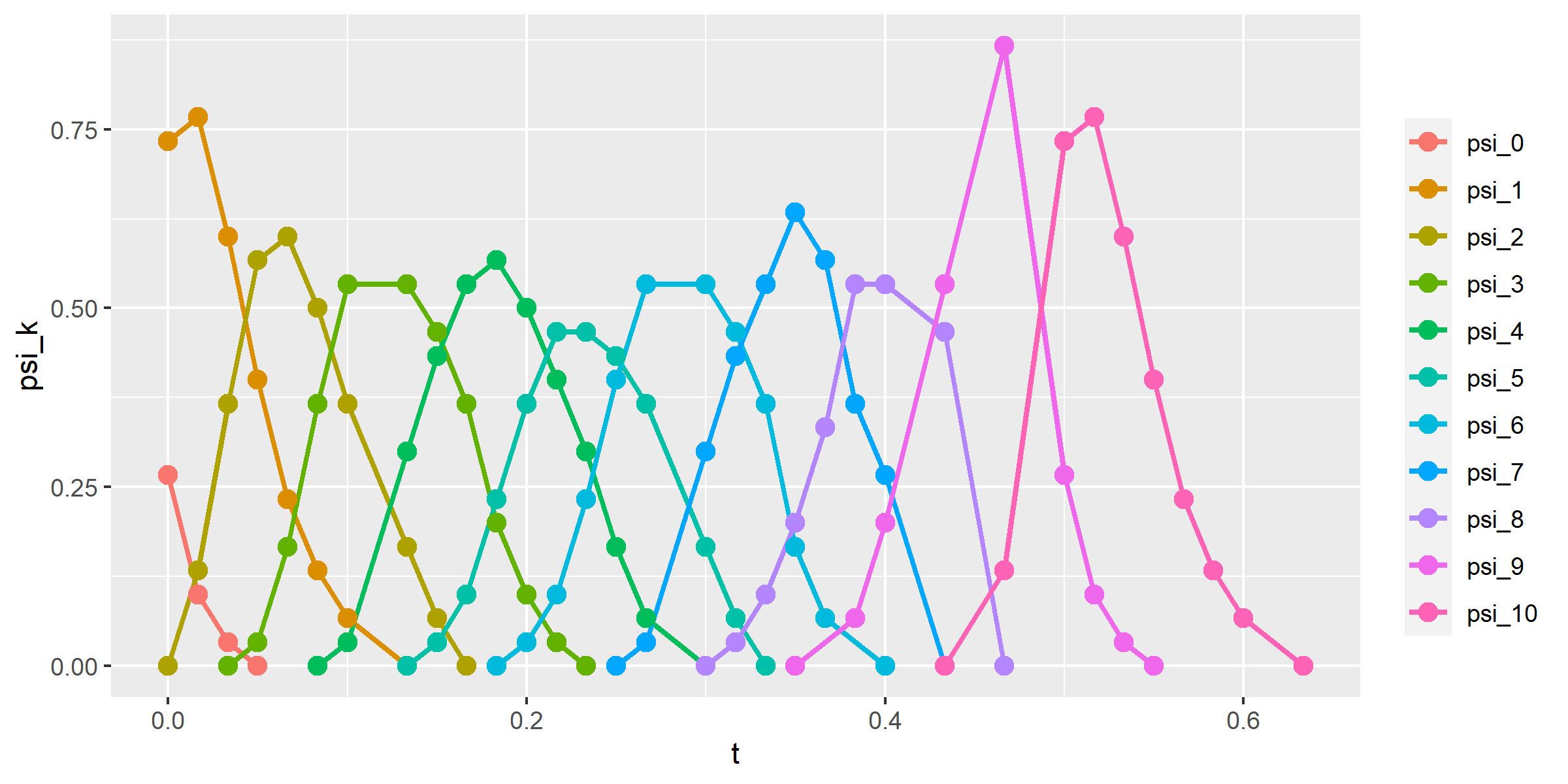

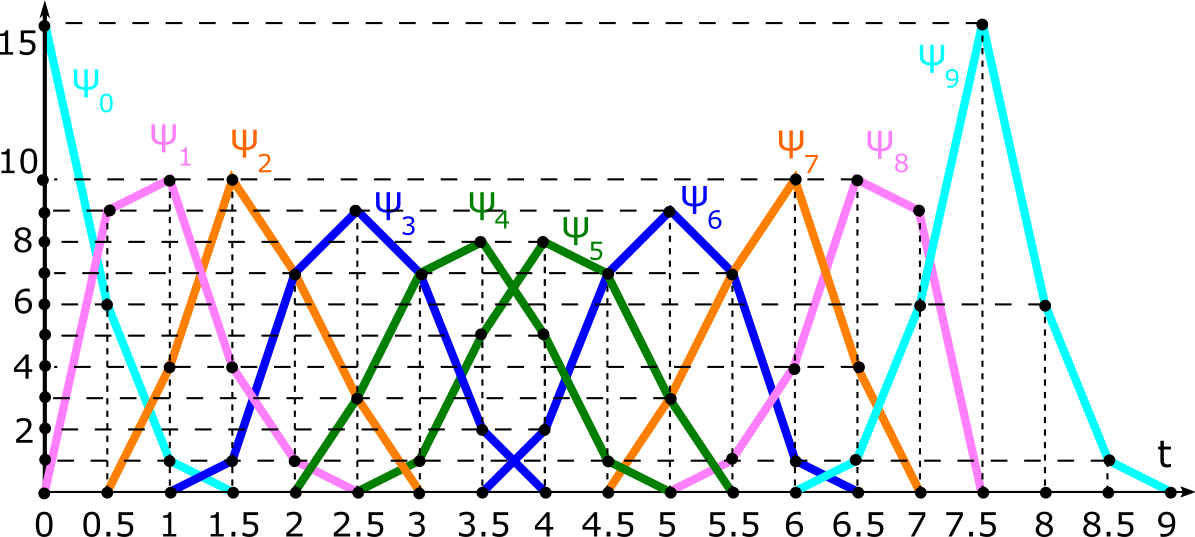

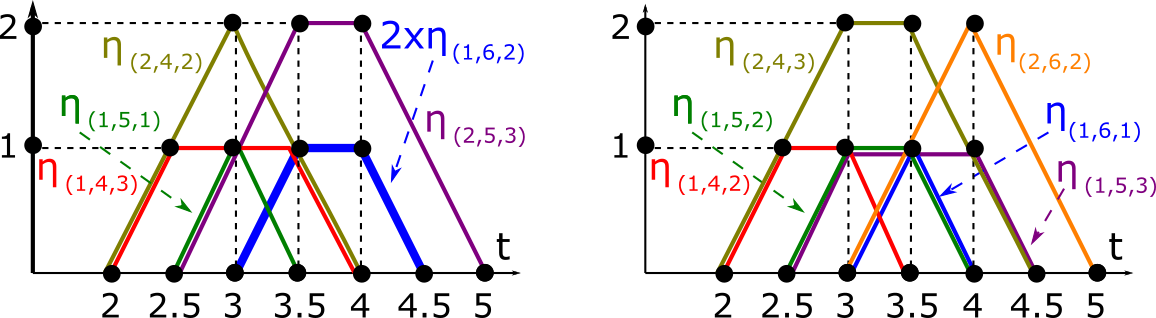

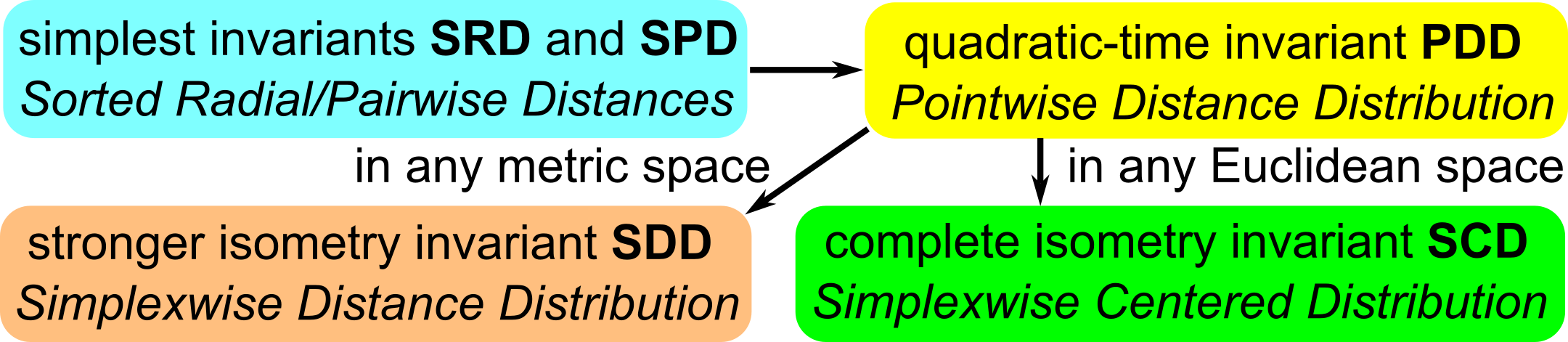

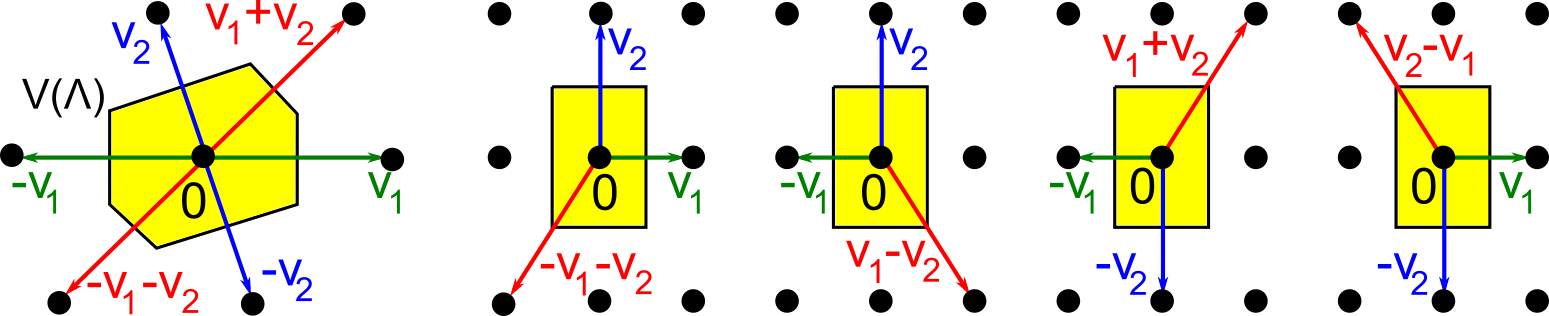

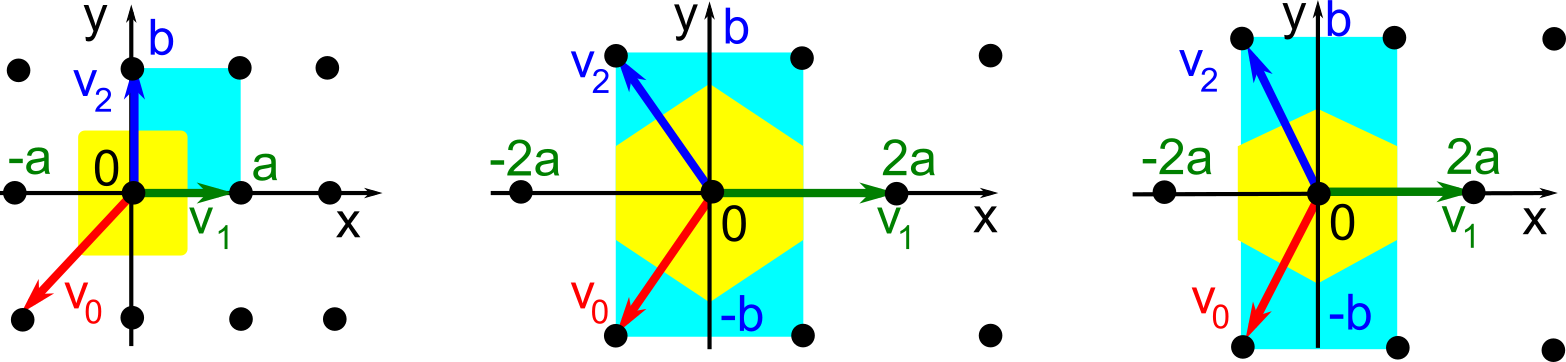

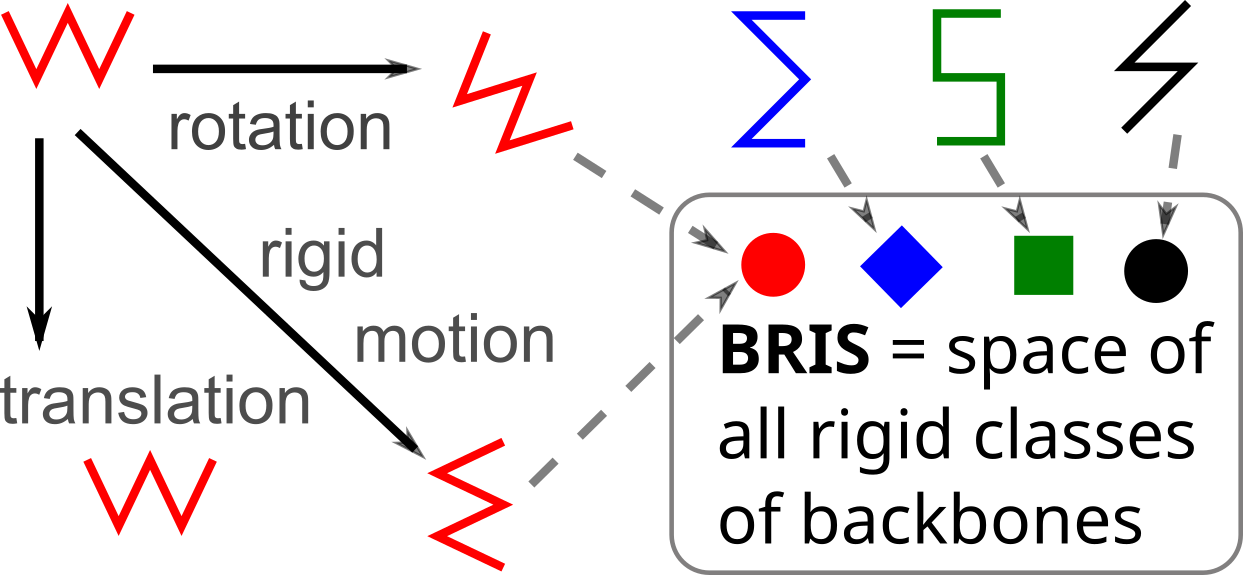

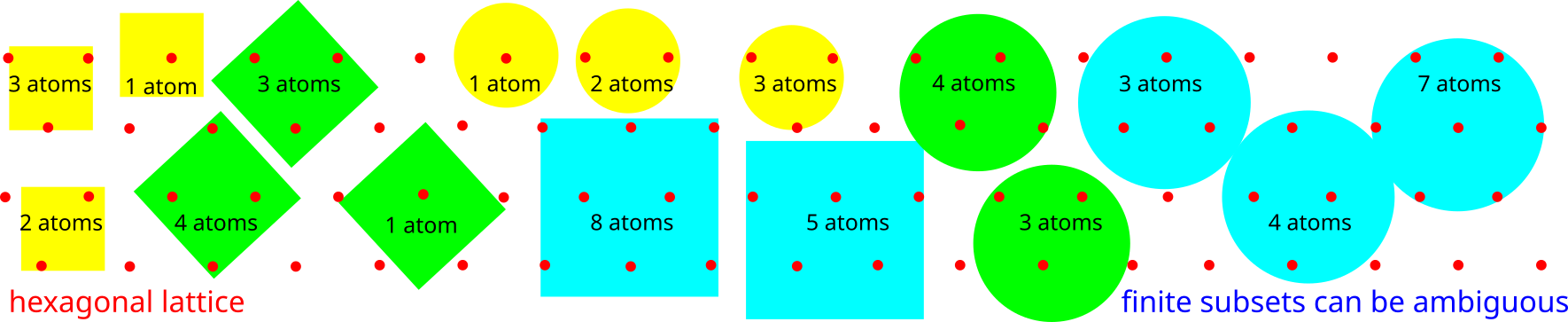

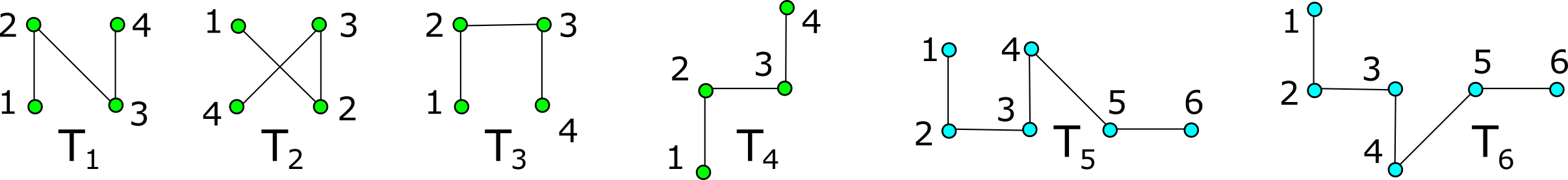

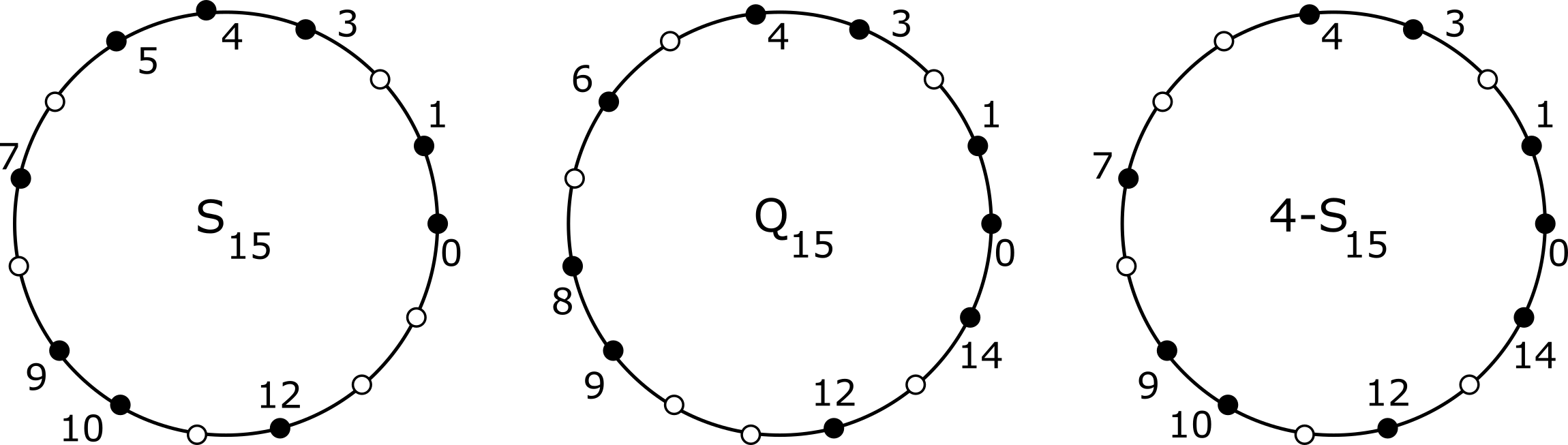

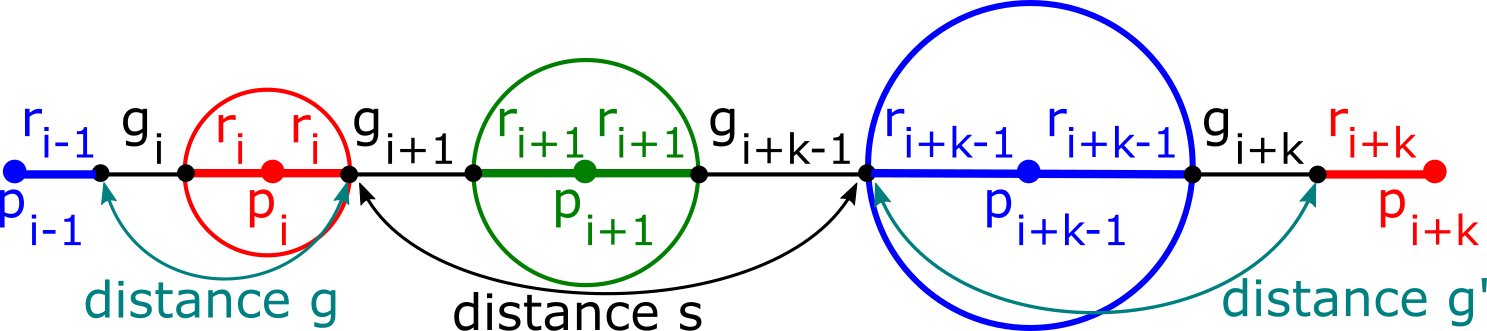

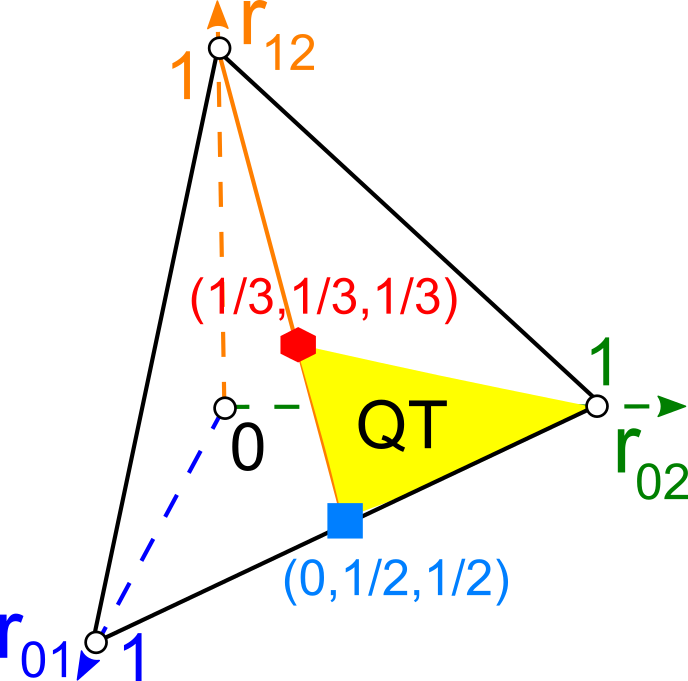

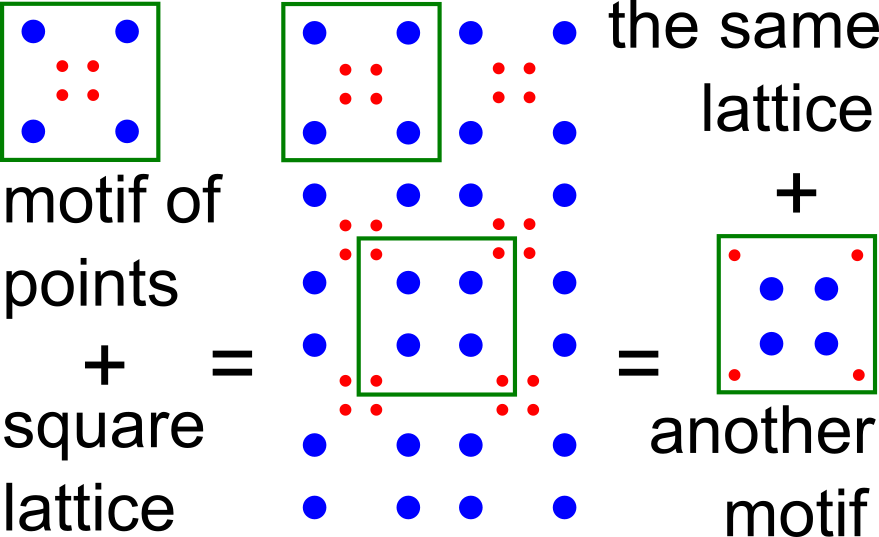

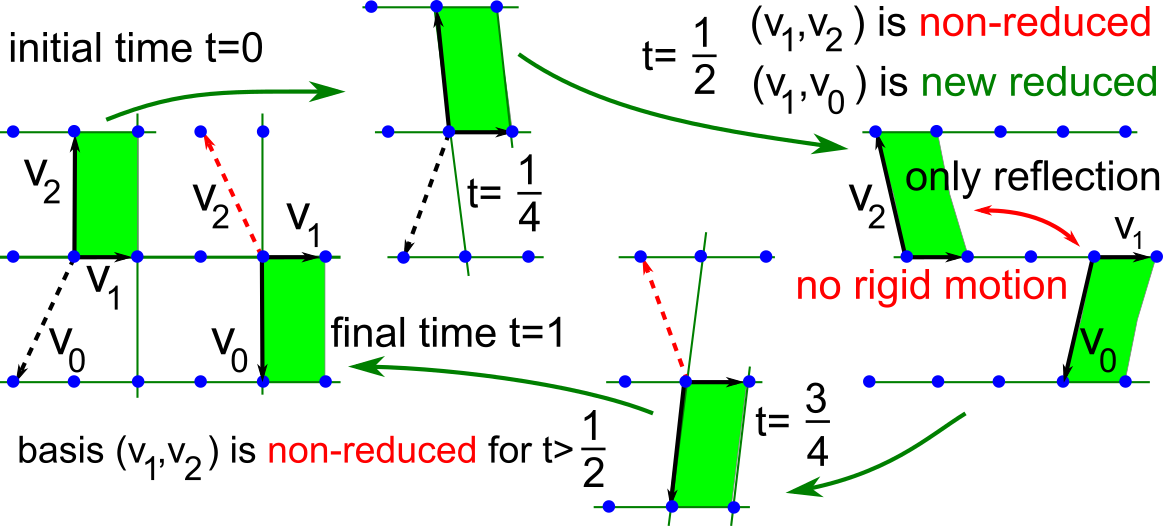

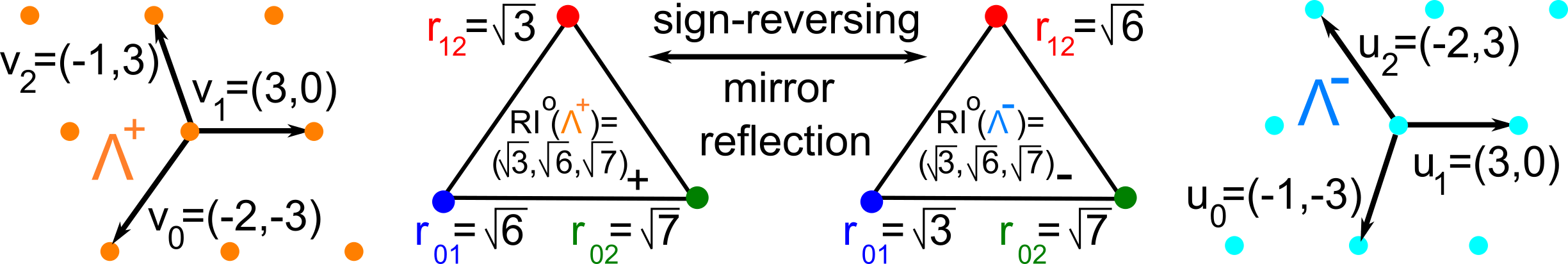

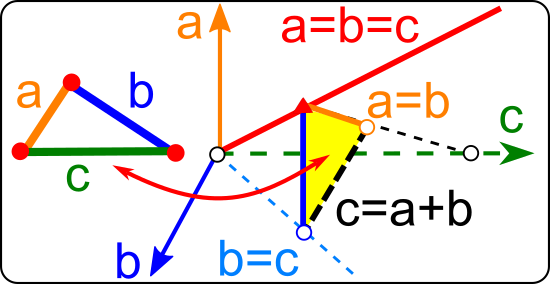

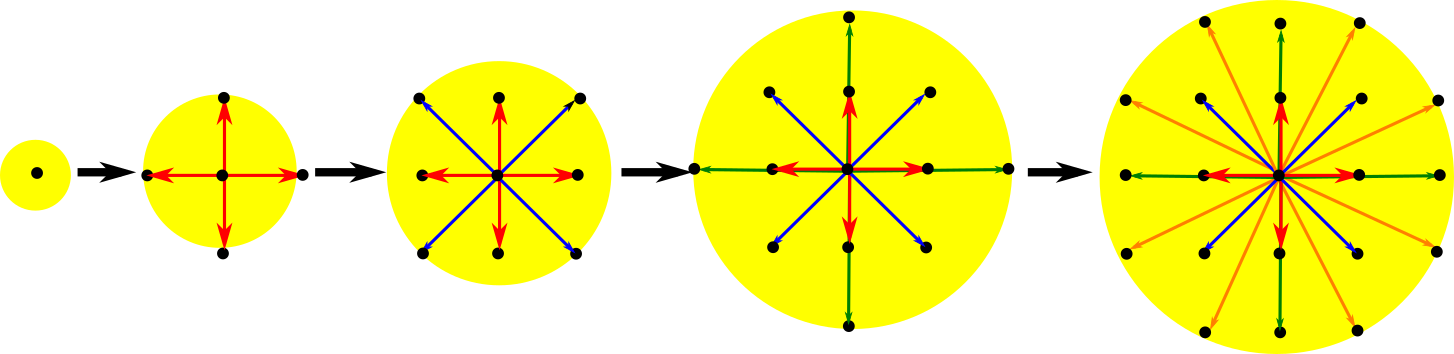

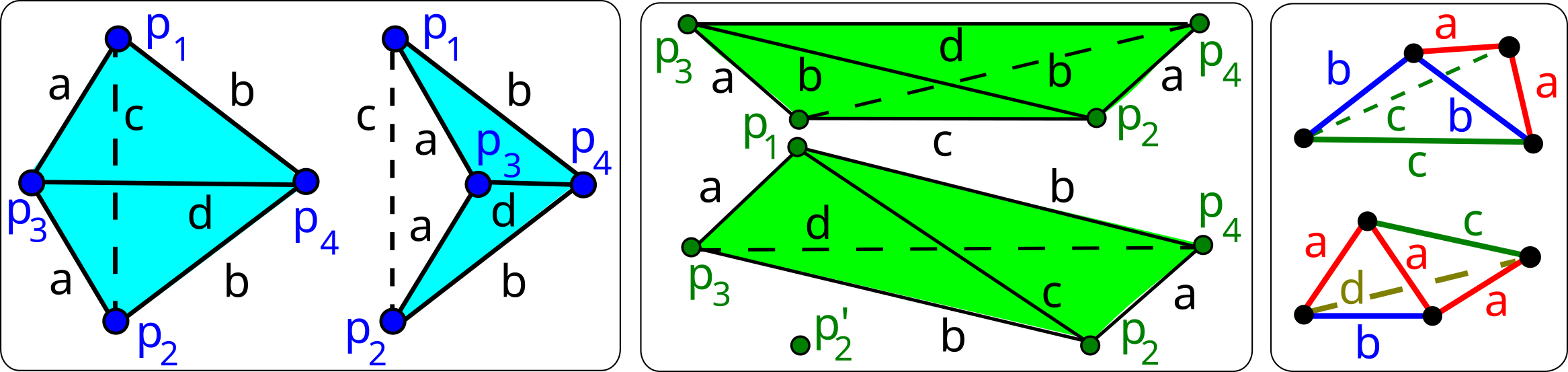

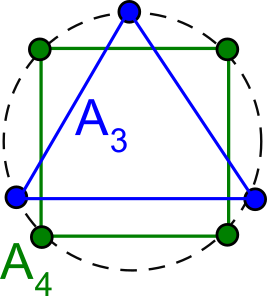

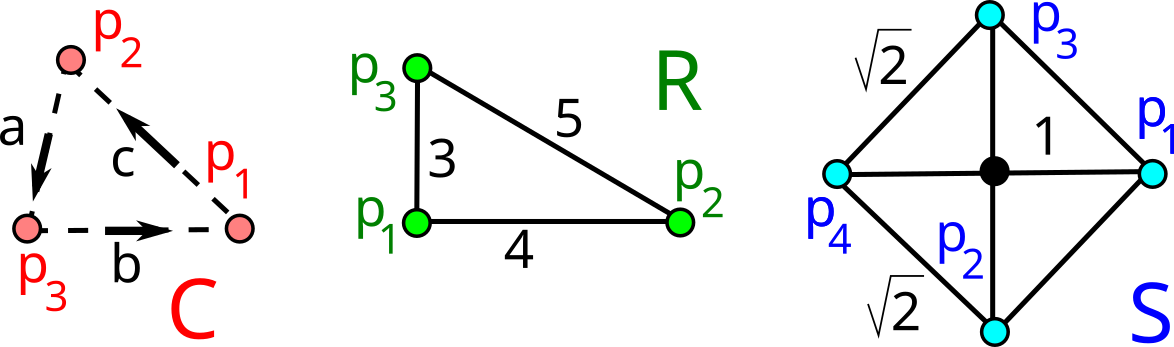

The first part of the book focuses on finite point sets. The most important result is a complete and continuous classification of all finite clouds of unordered points under rigid motion in any Euclidean space. The key challenge was to avoid the exponential complexity arising from permutations of the given unordered points. For a fixed dimension of the ambient Euclidean space, the times of all algorithms for the resulting invariants and distance metrics depend polynomially on the number of points.

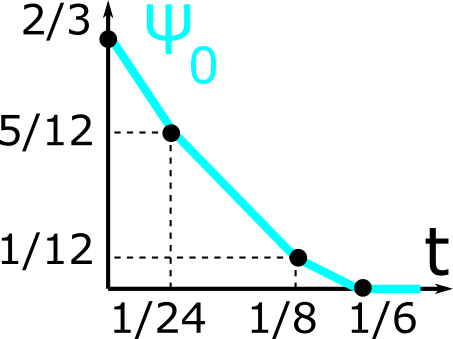

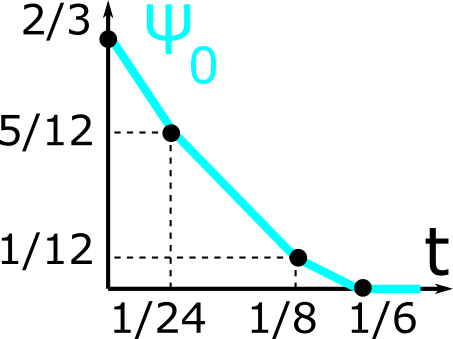

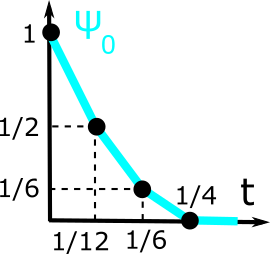

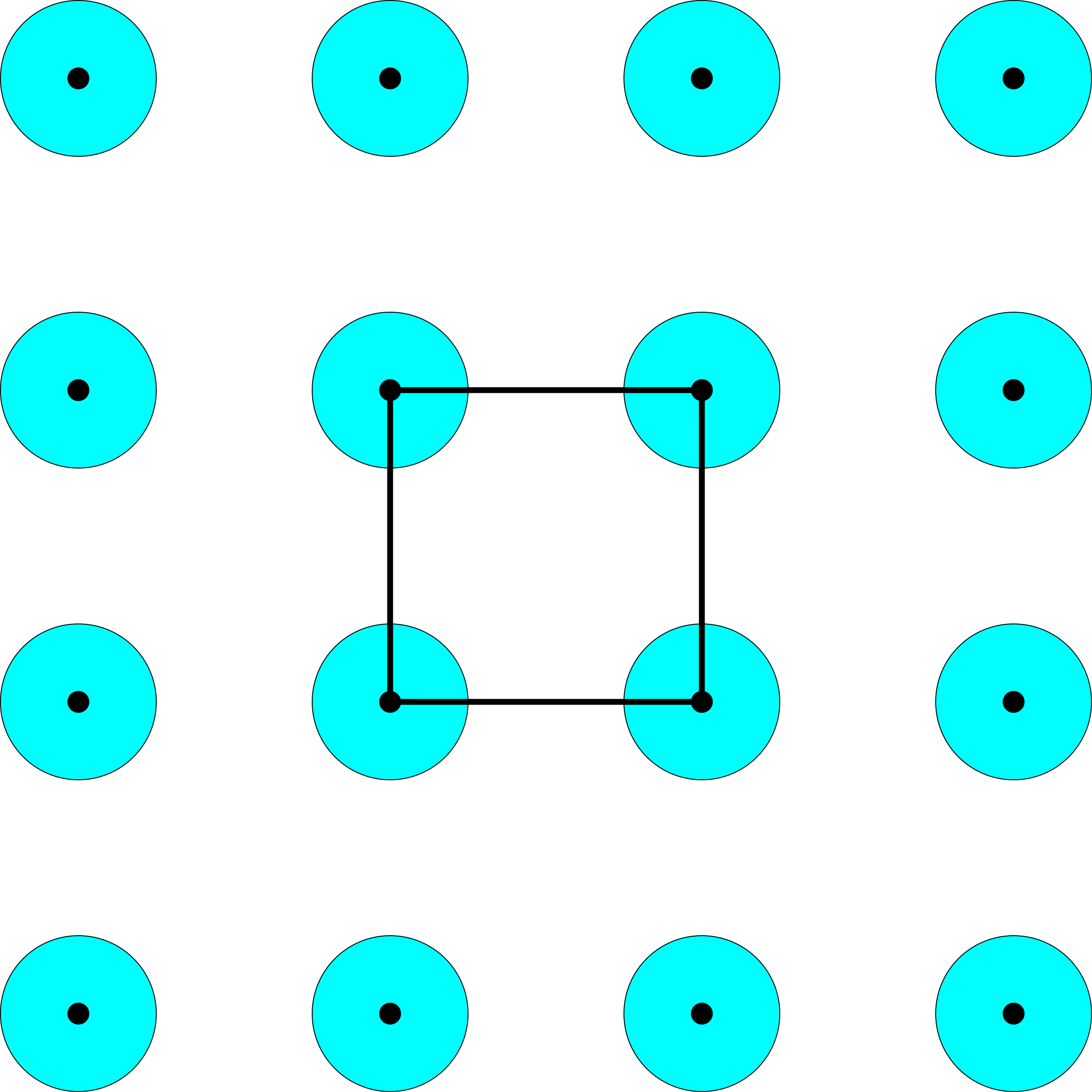

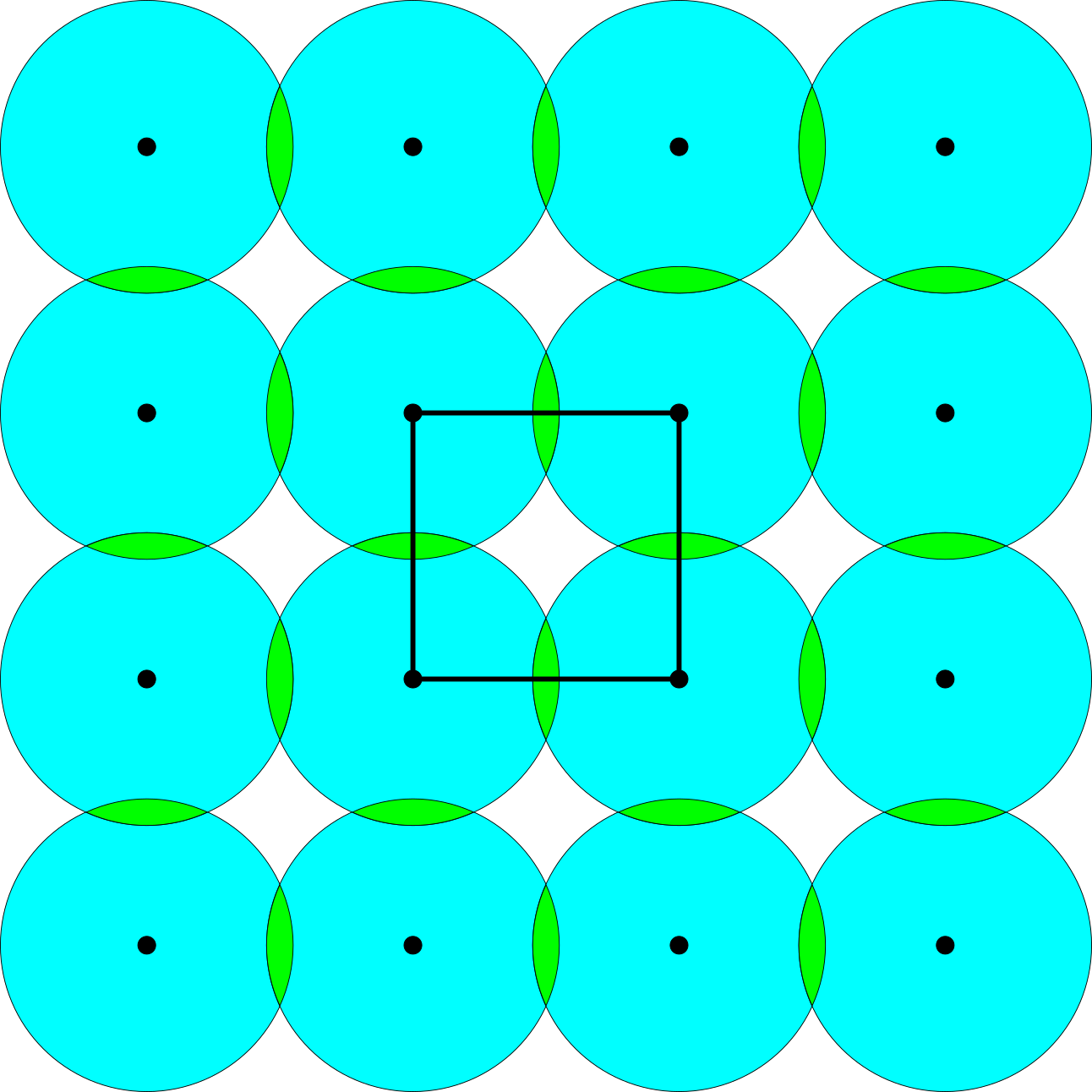

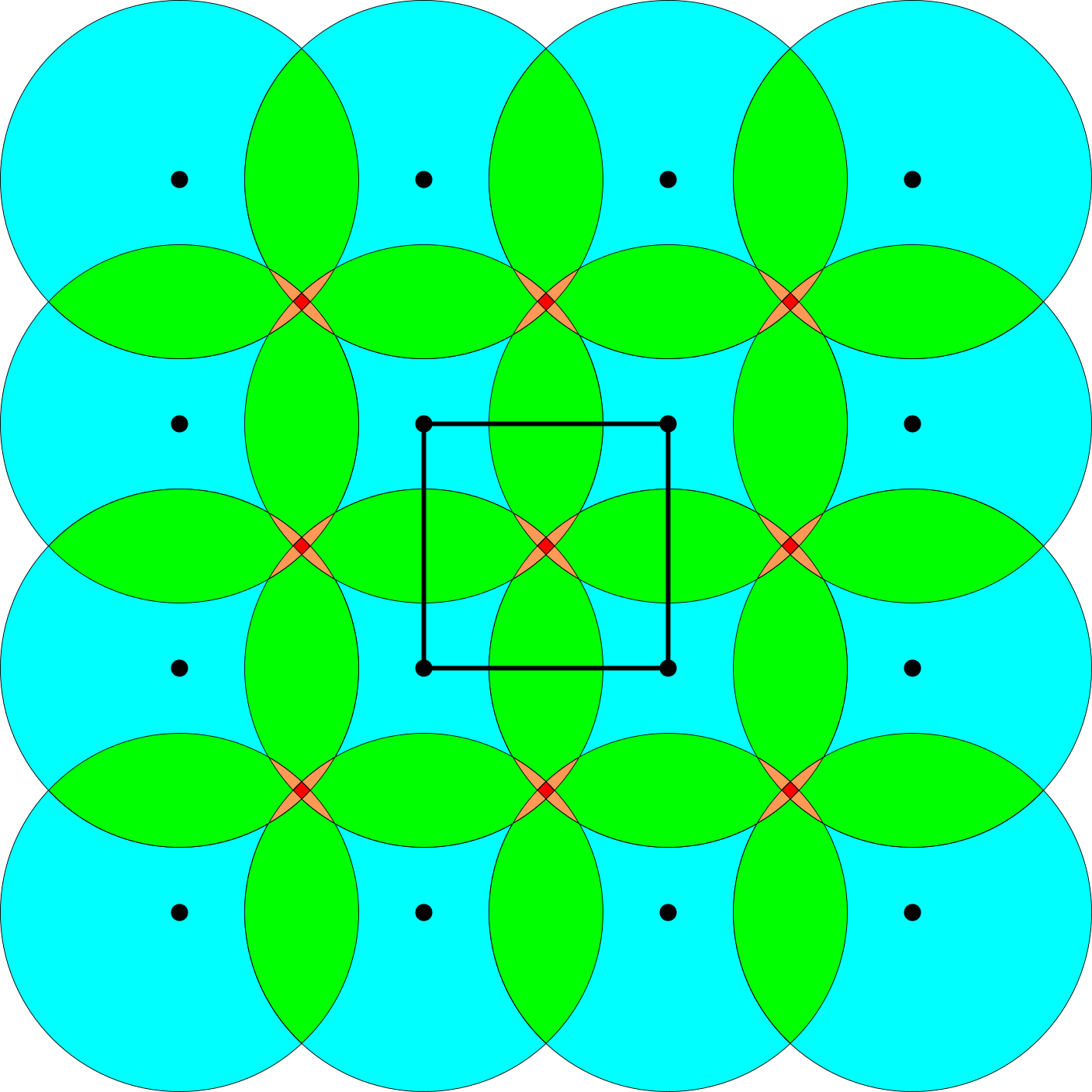

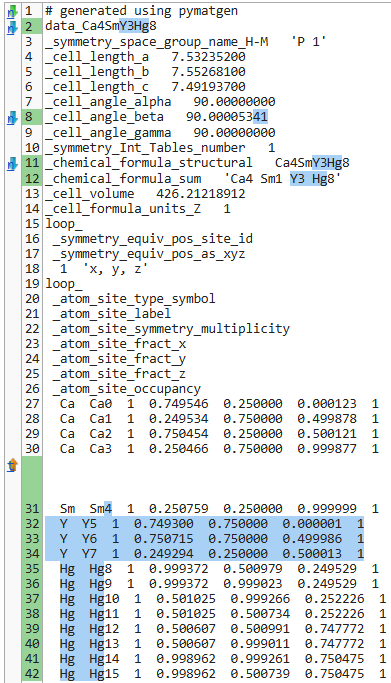

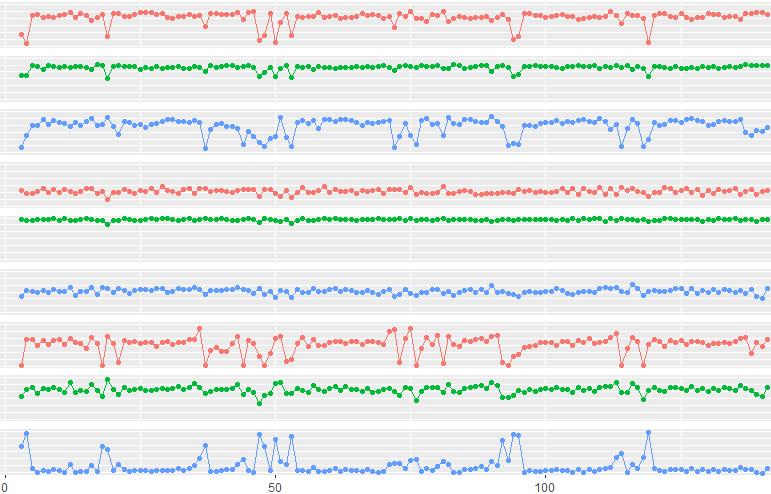

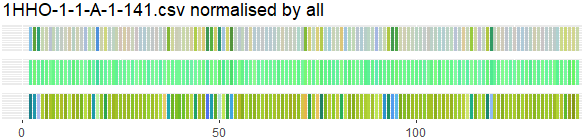

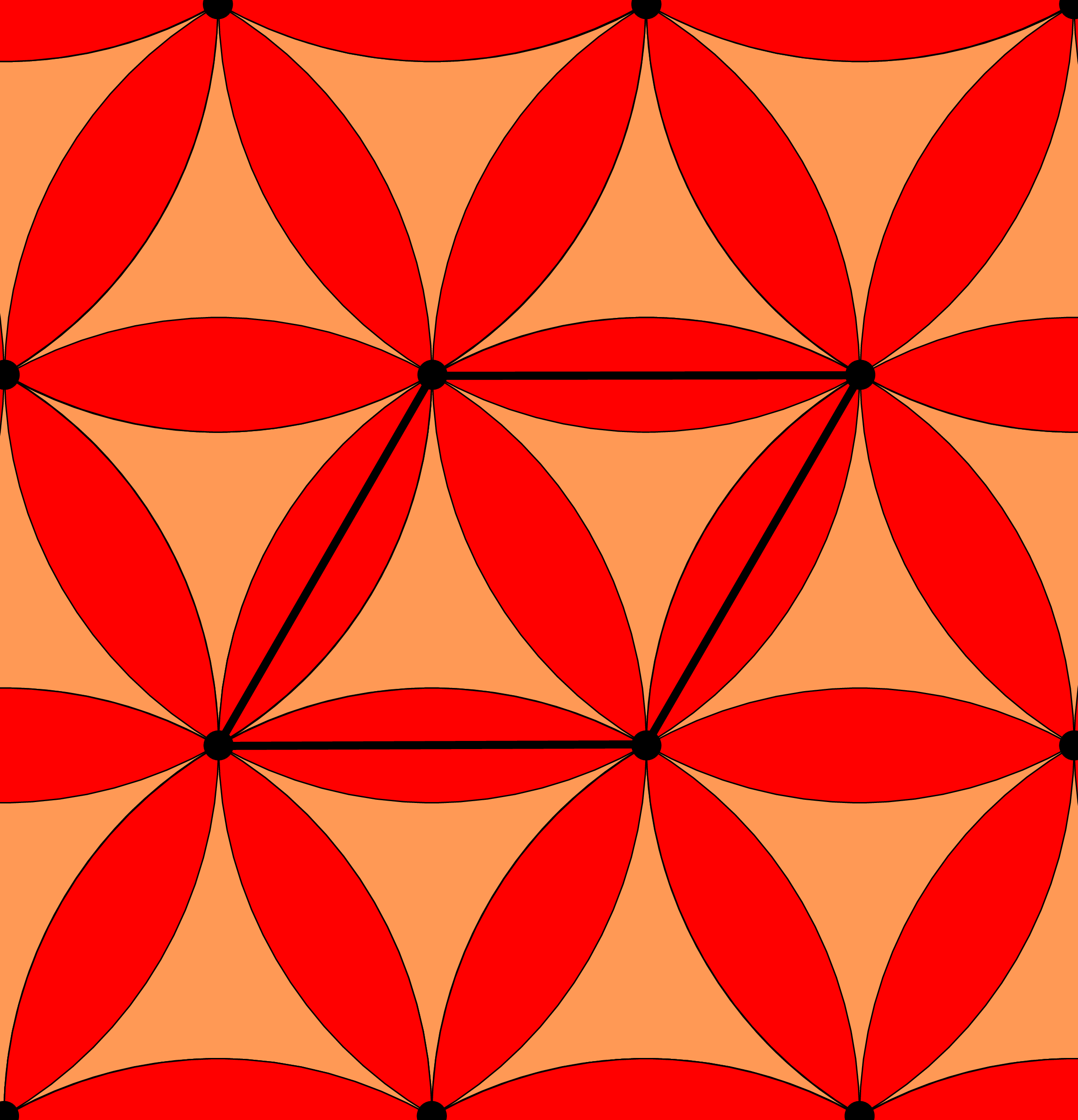

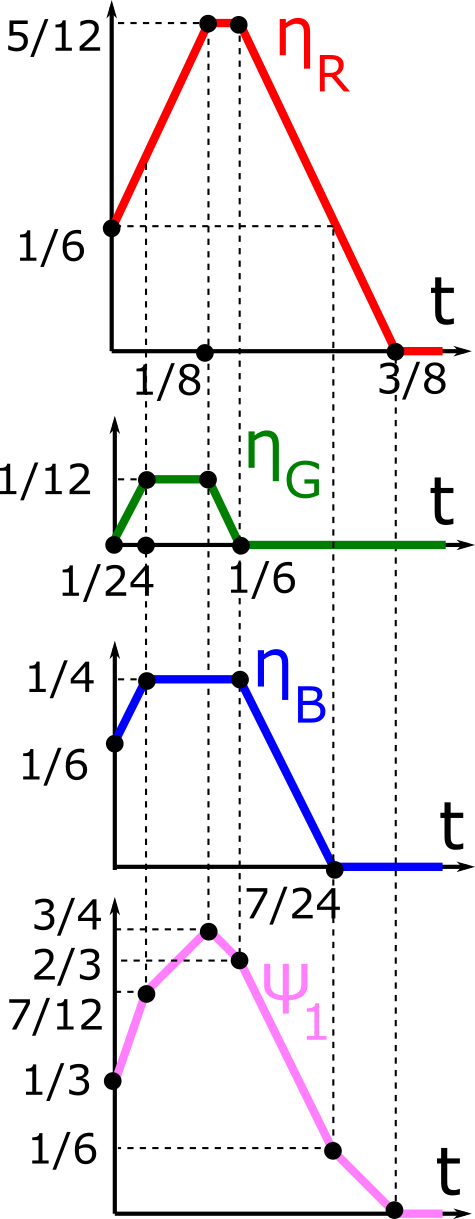

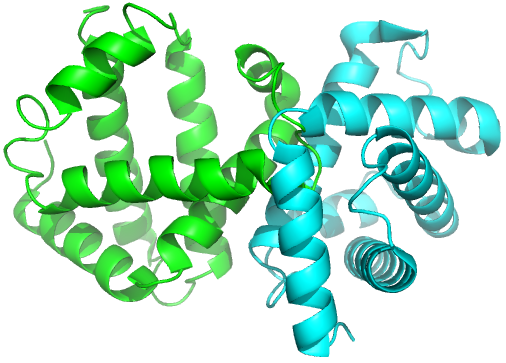

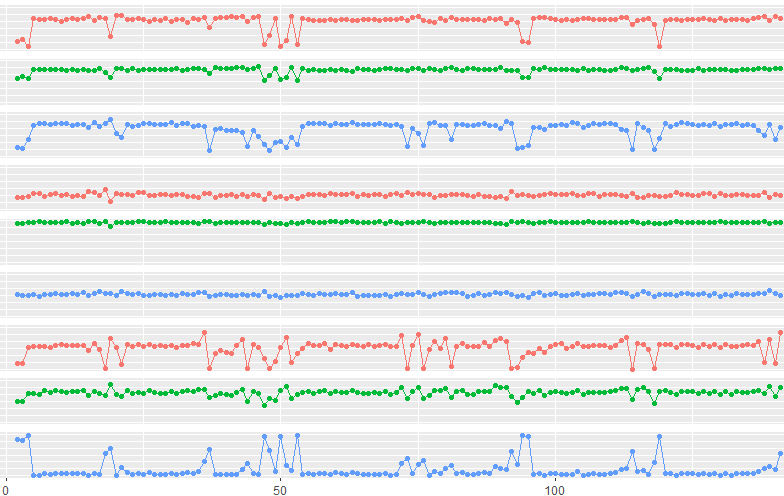

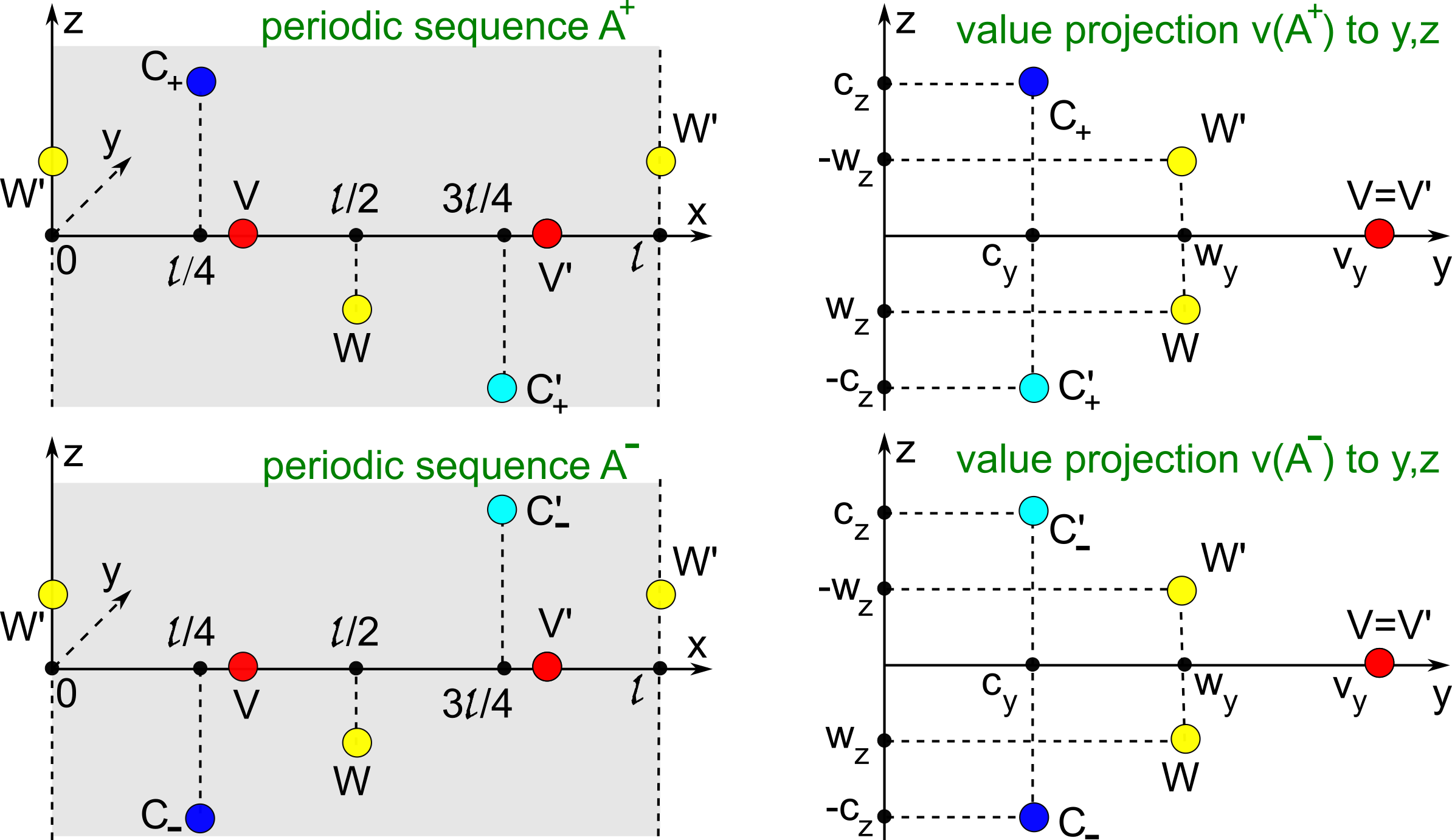

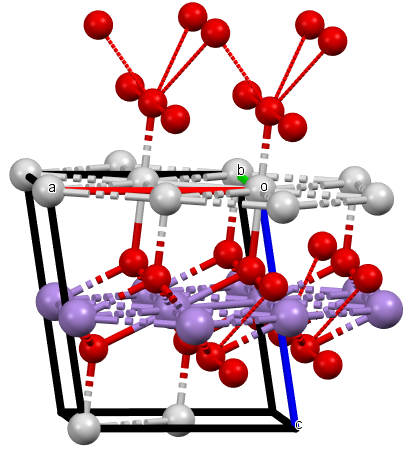

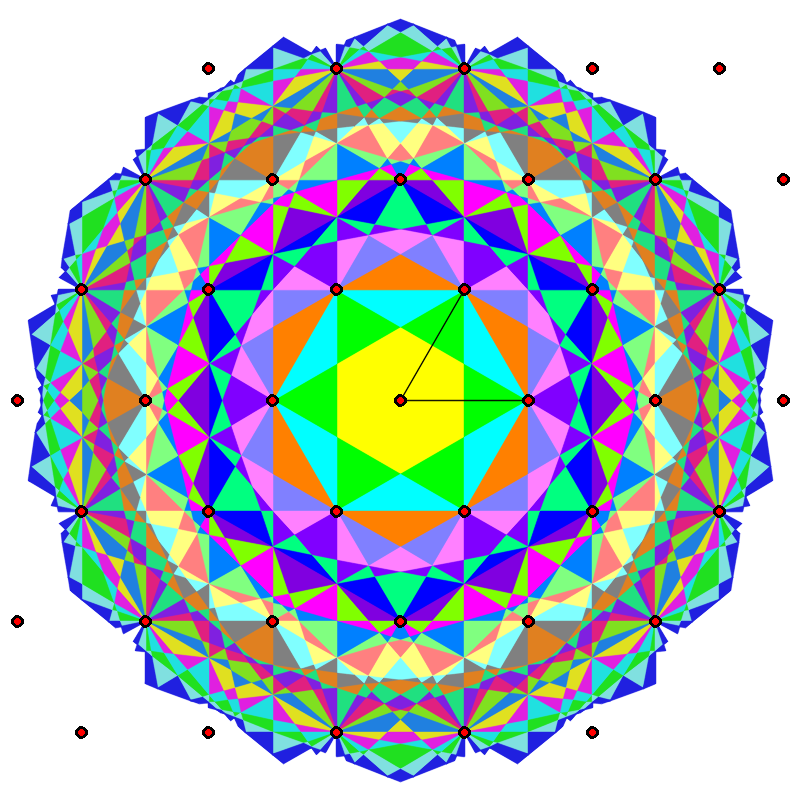

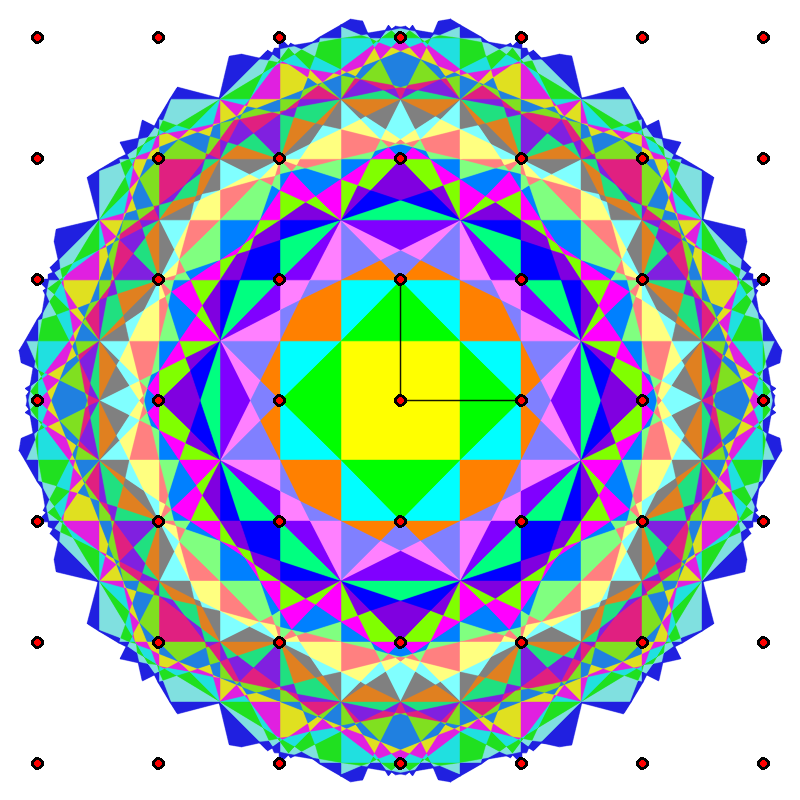

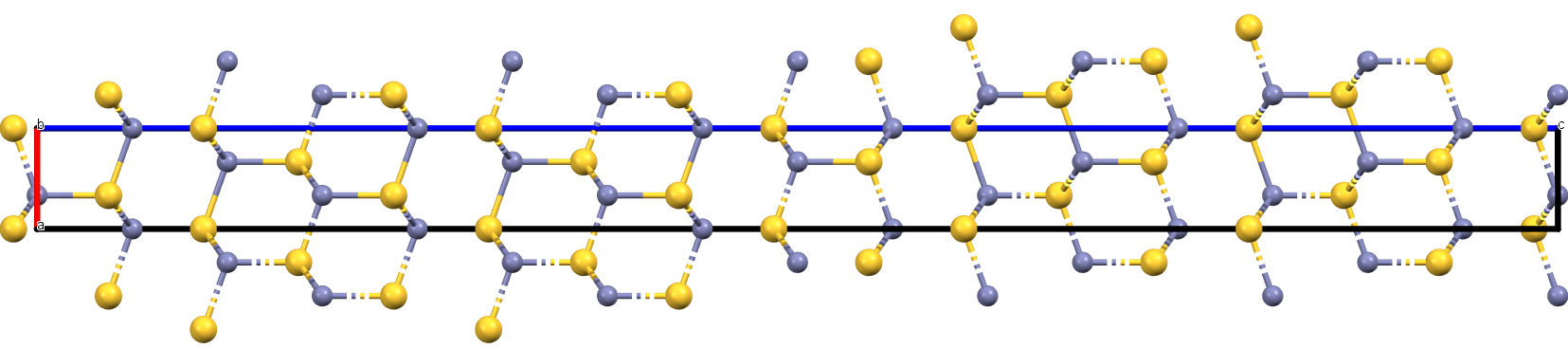

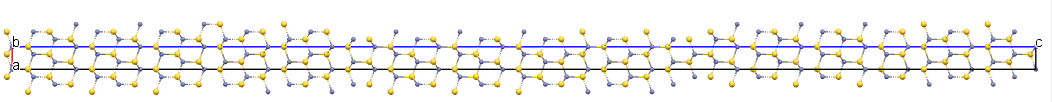

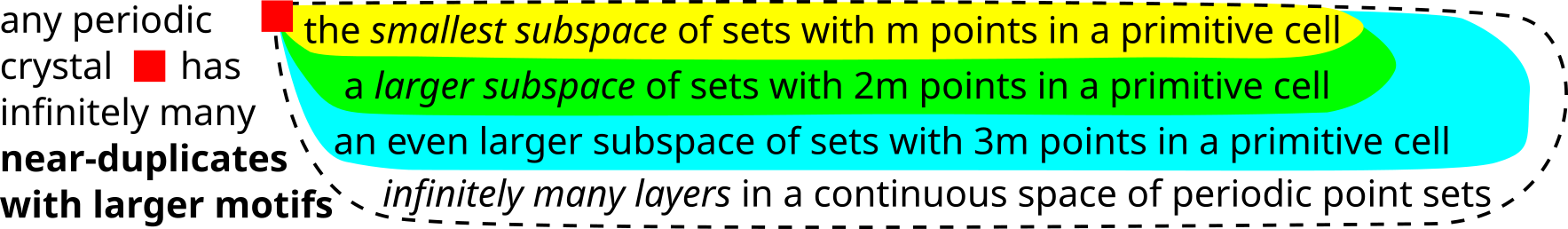

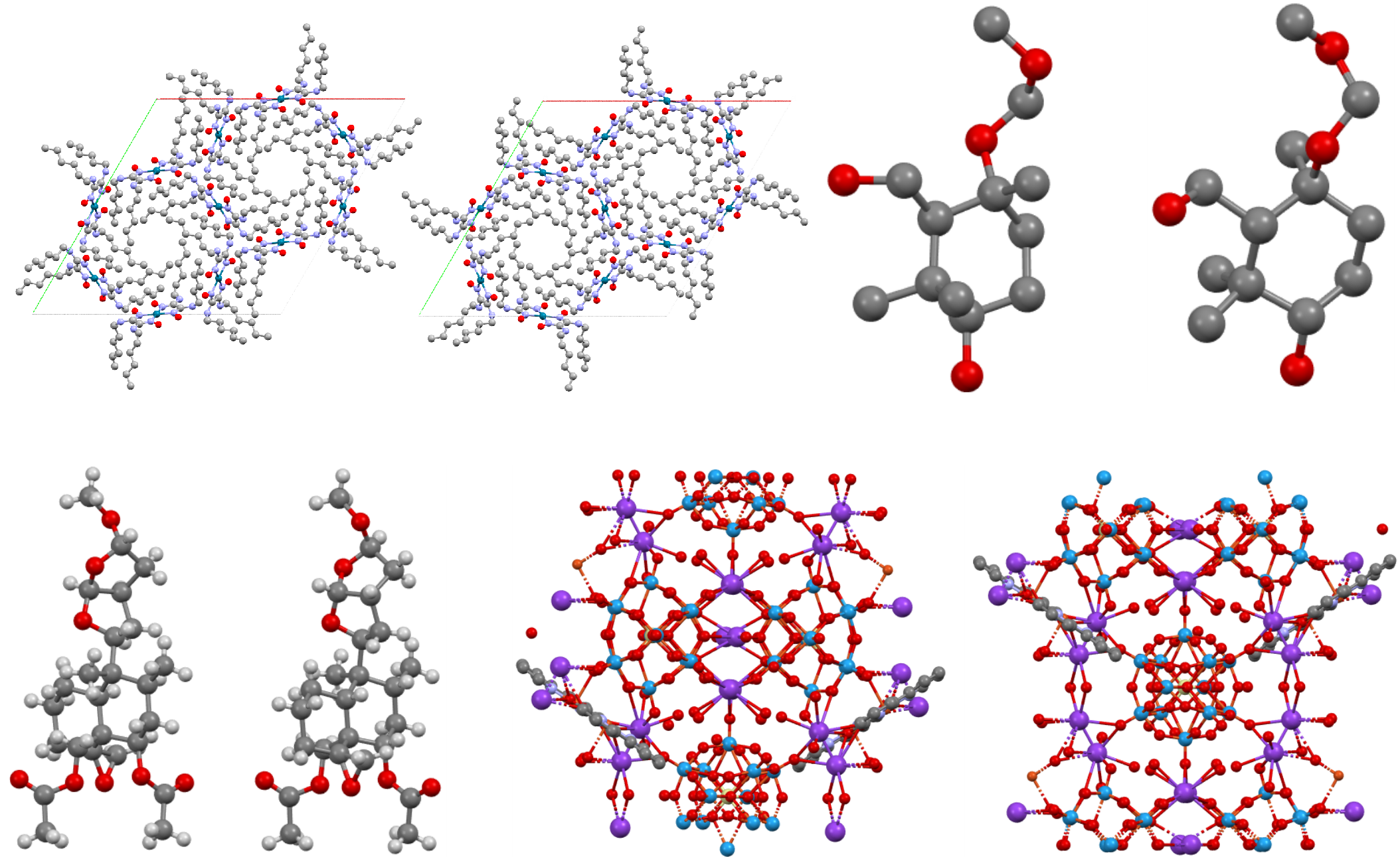

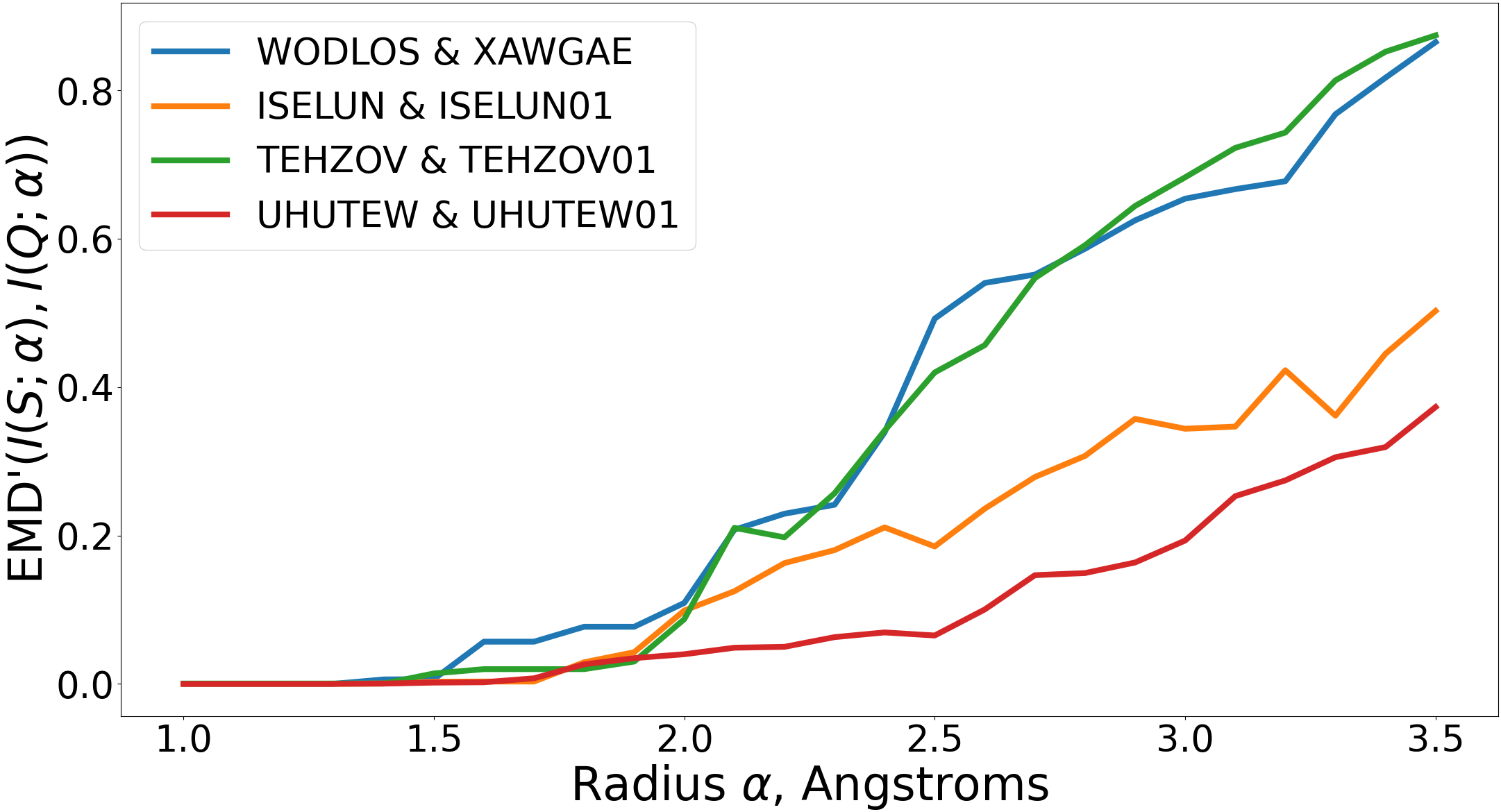

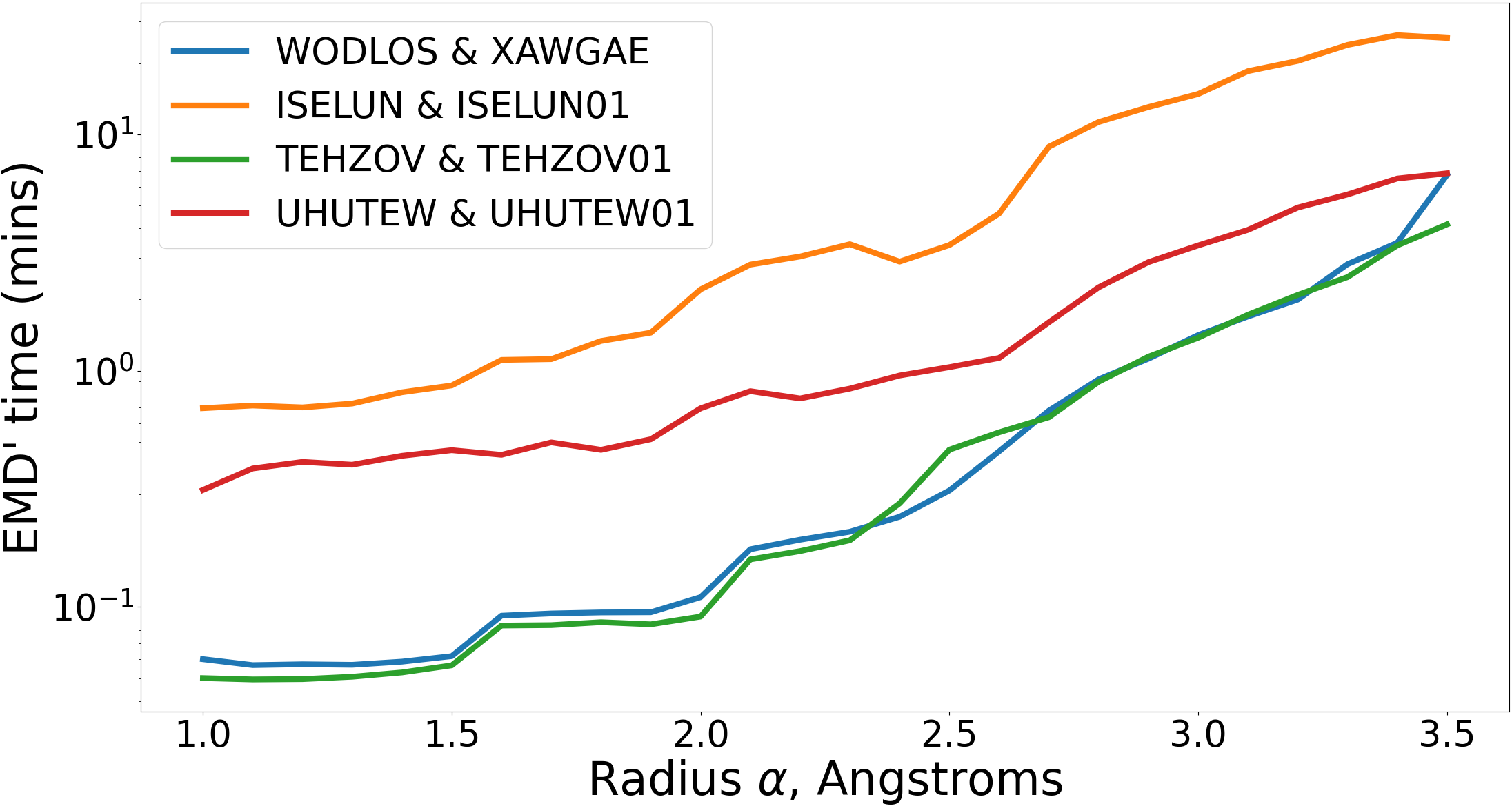

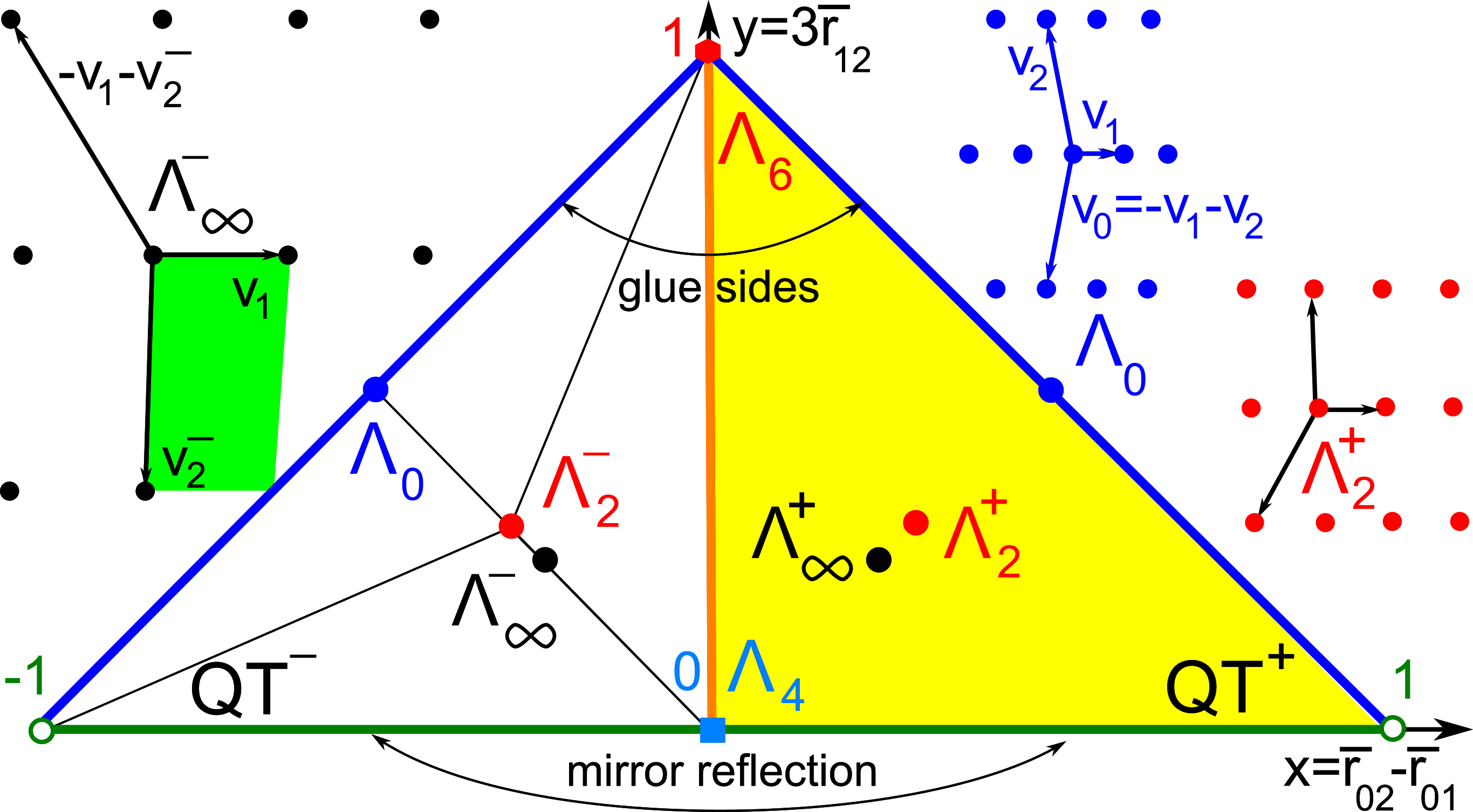

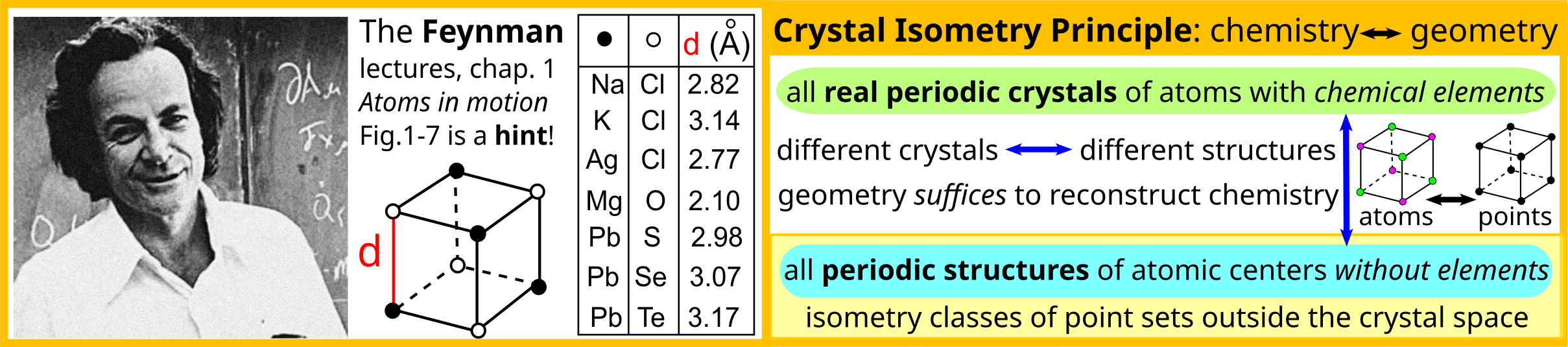

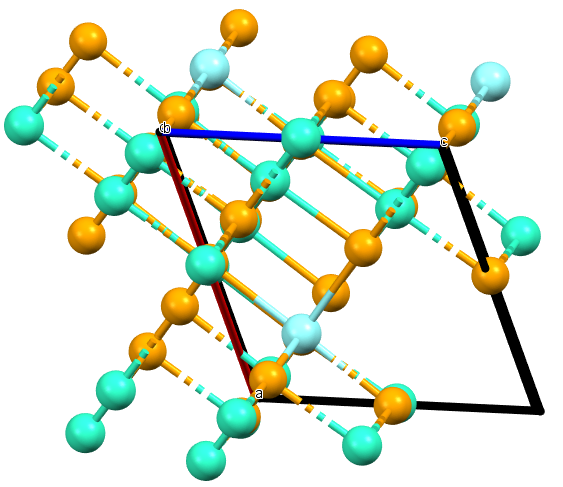

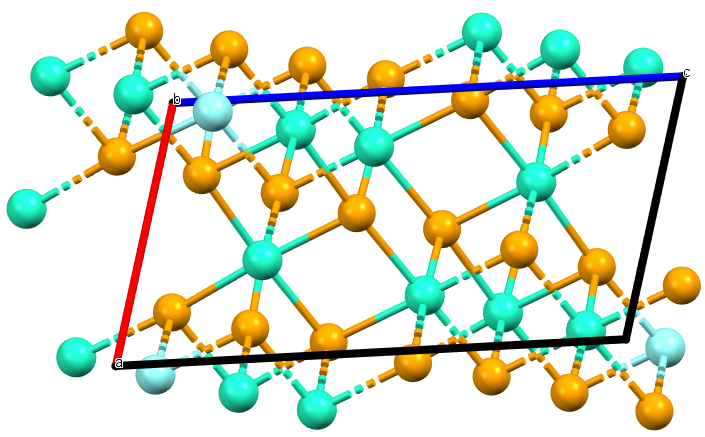

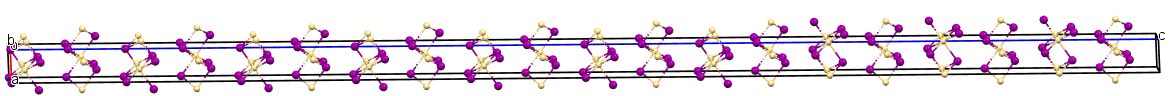

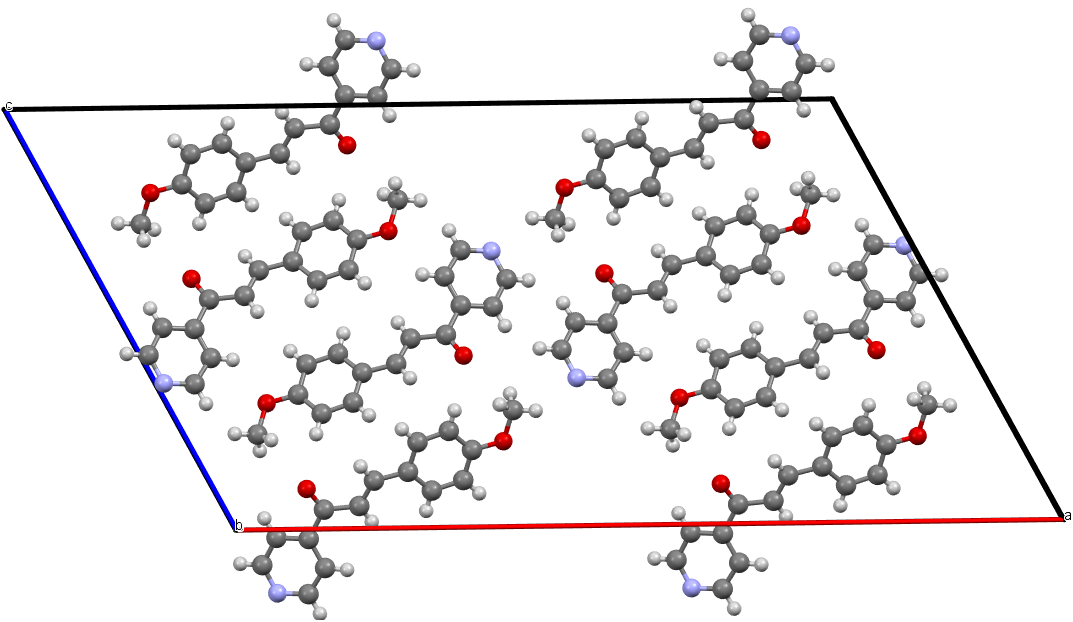

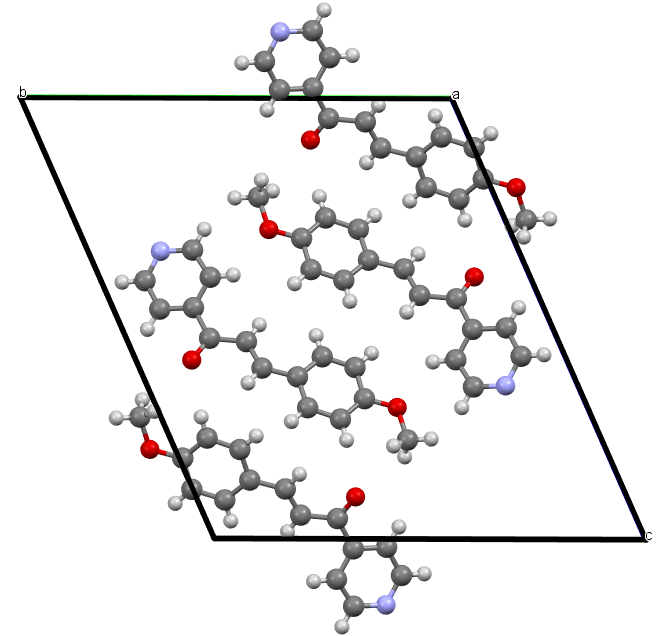

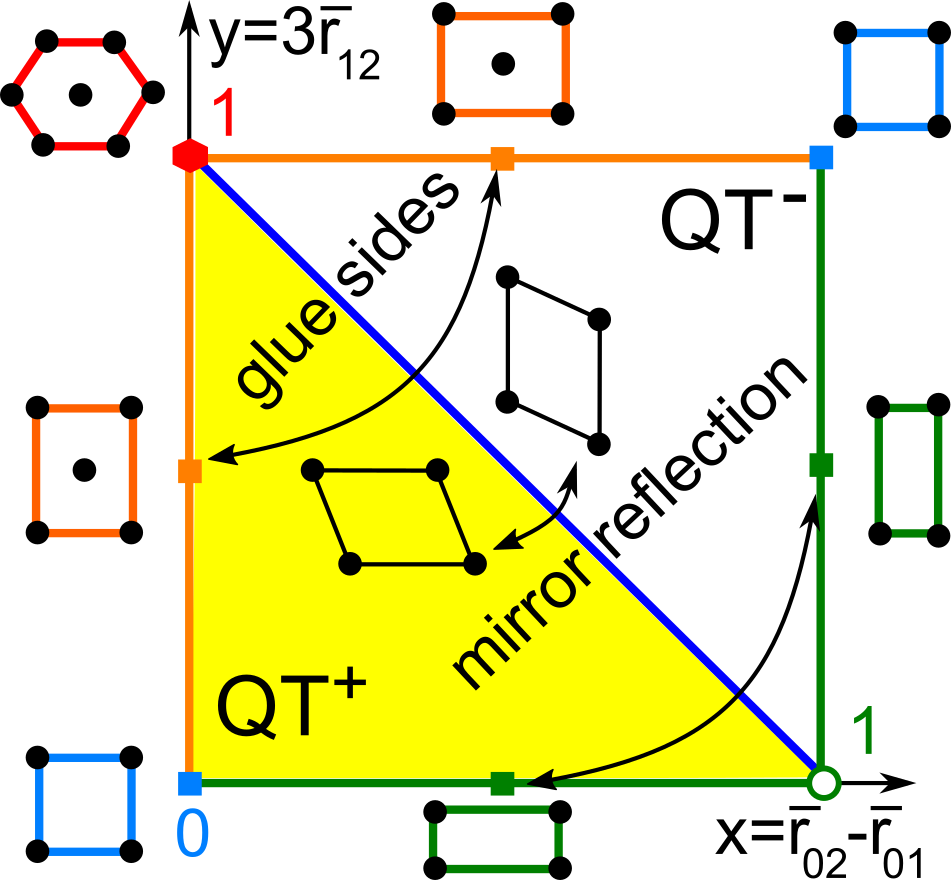

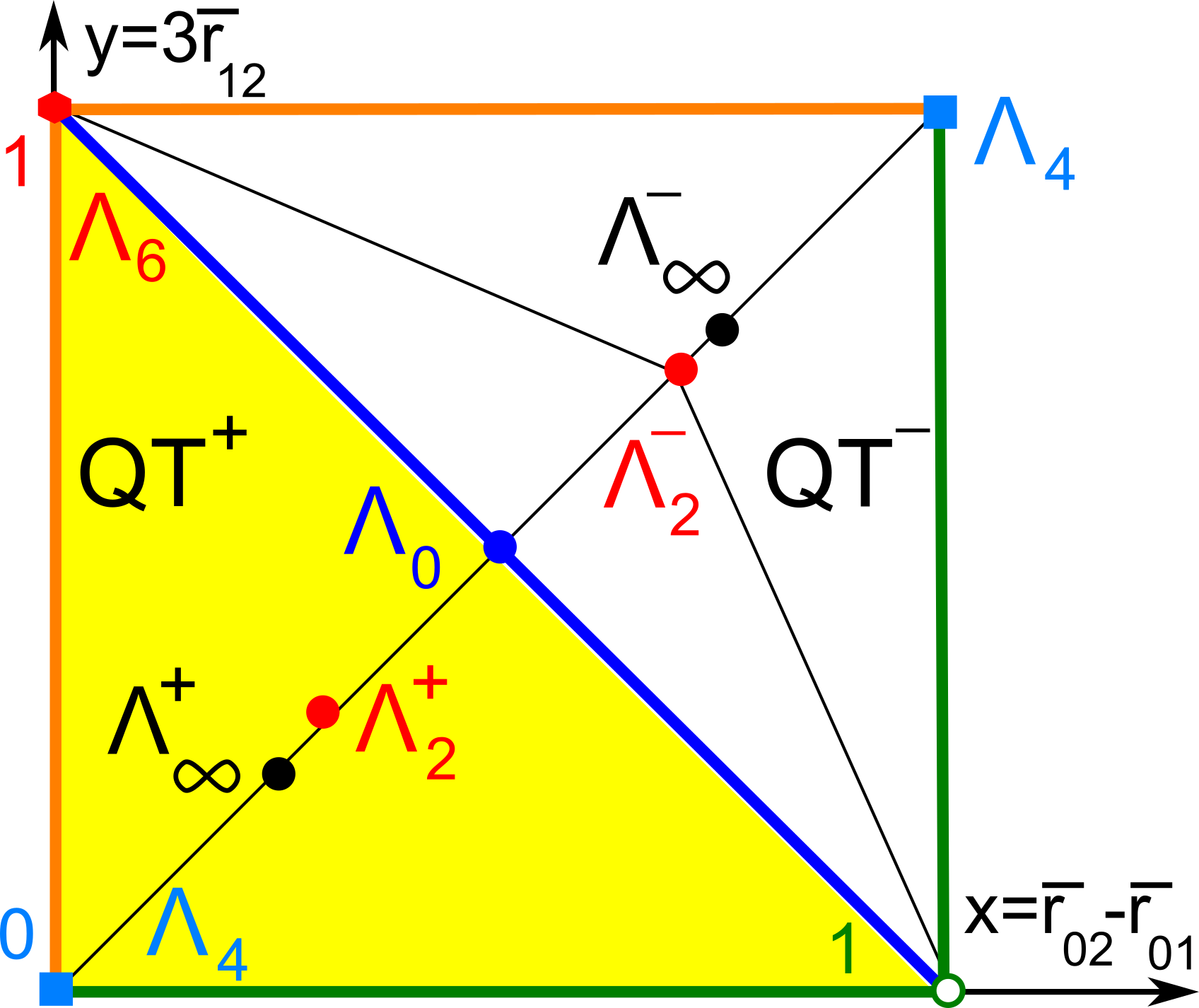

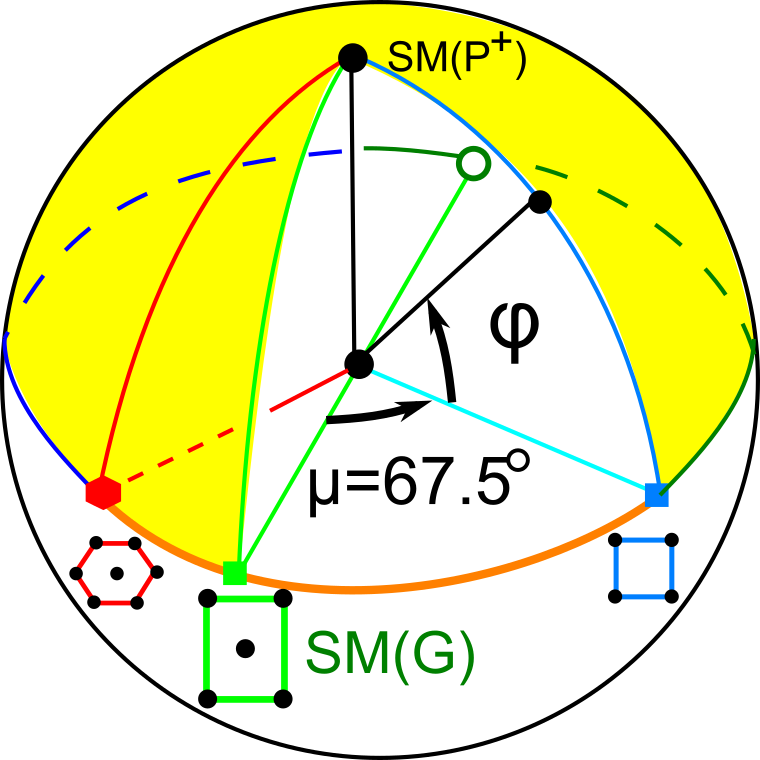

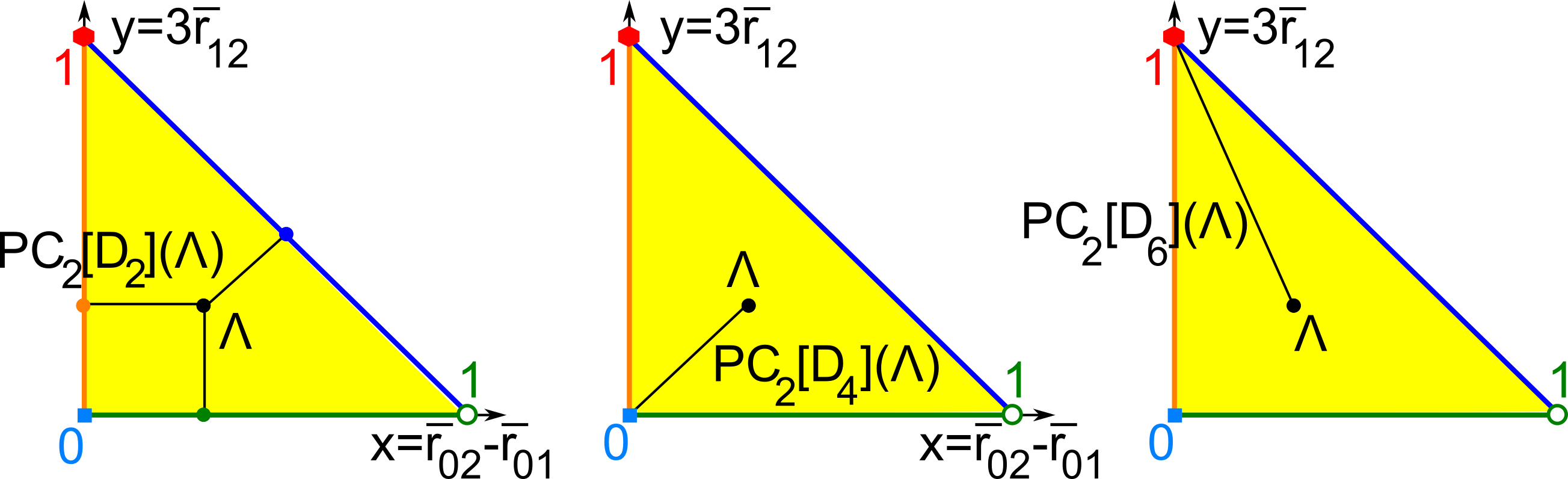

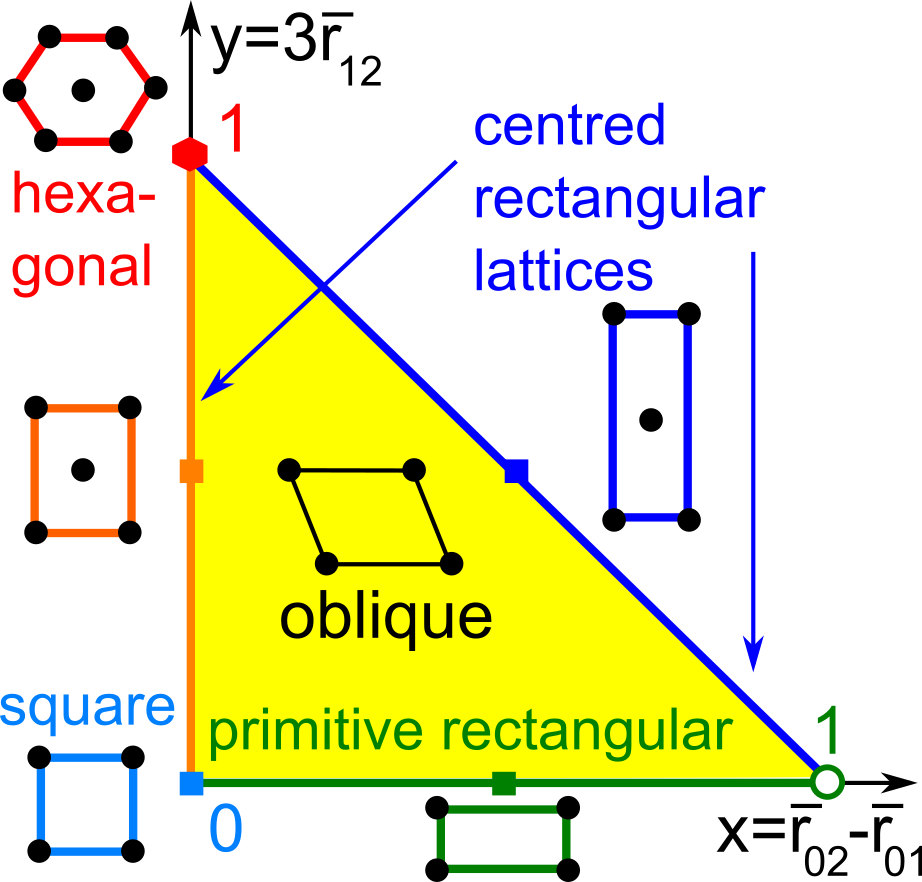

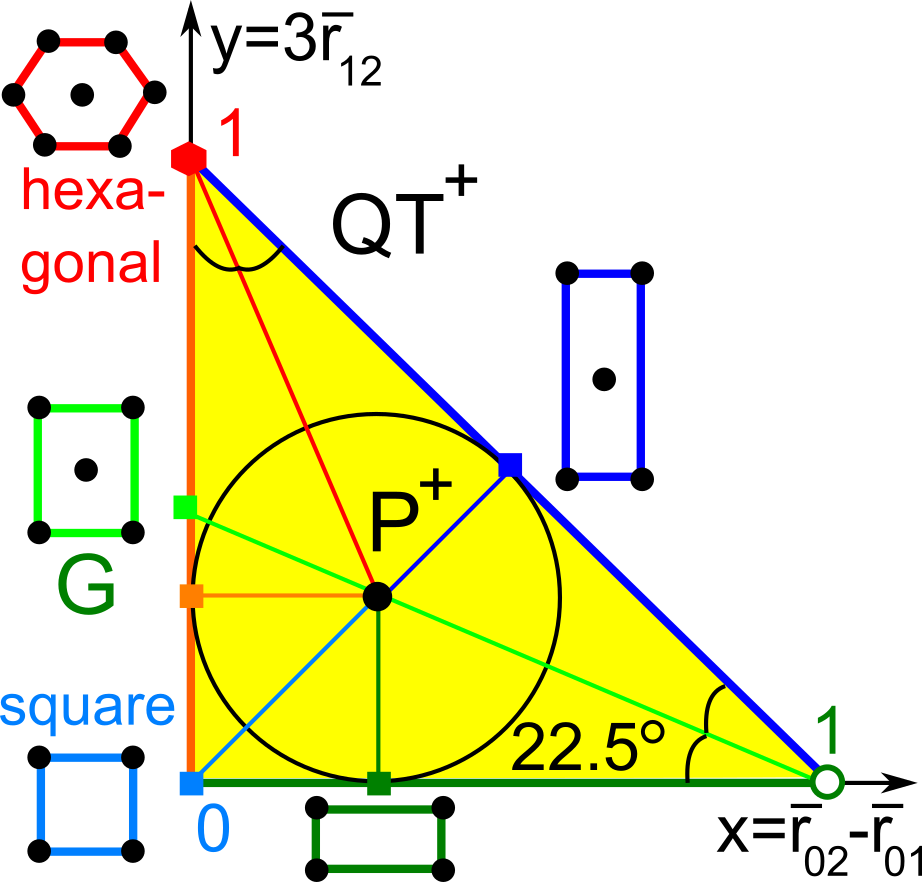

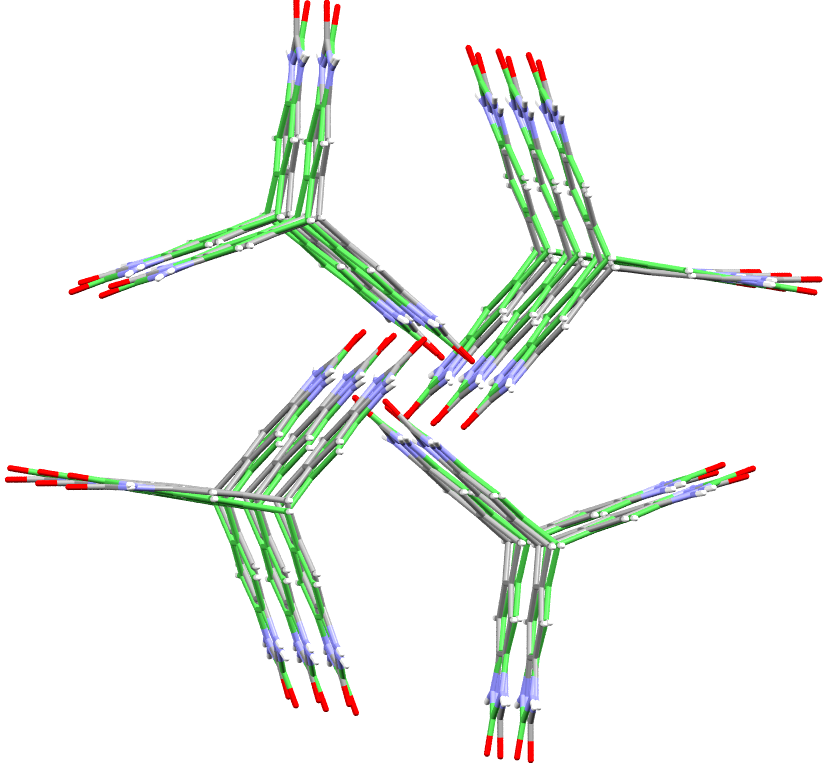

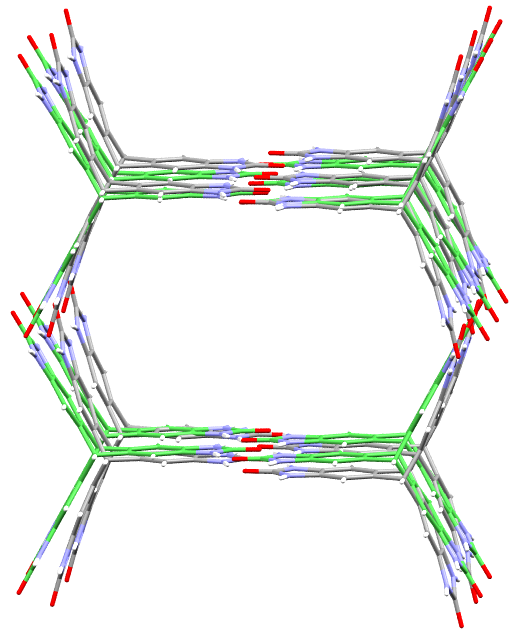

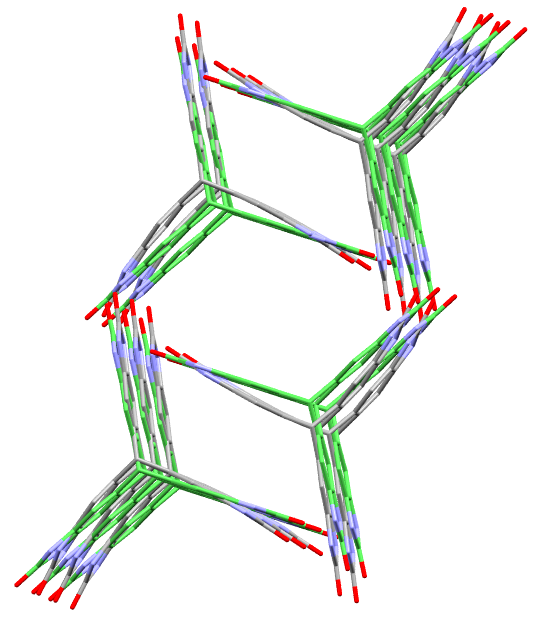

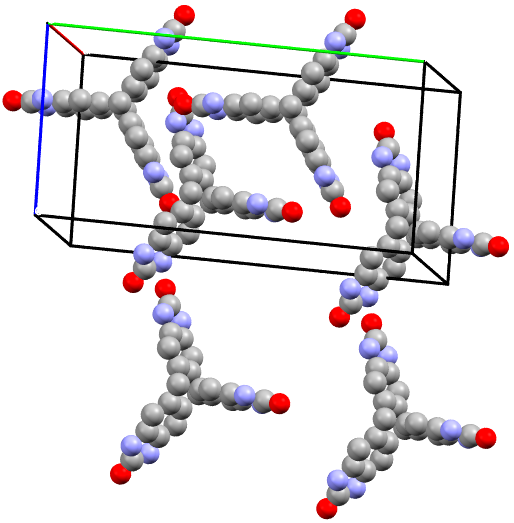

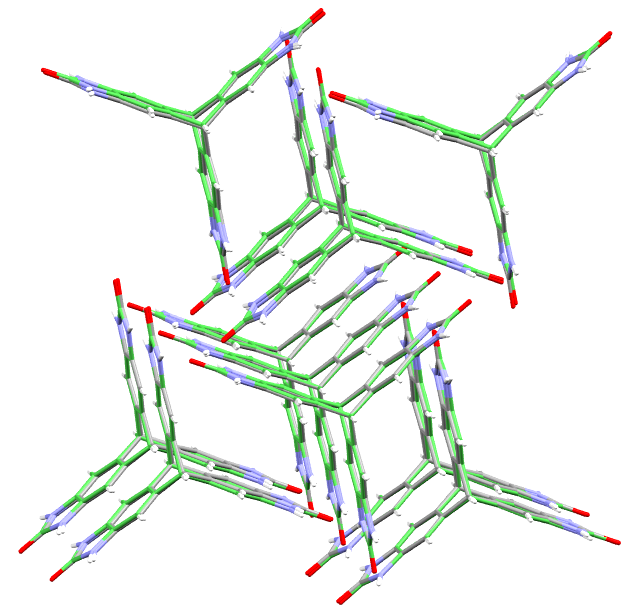

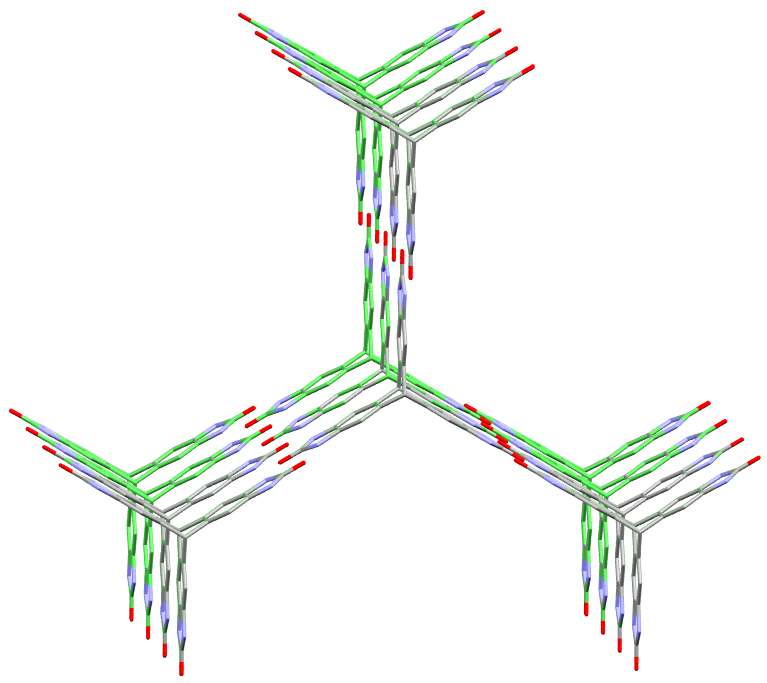

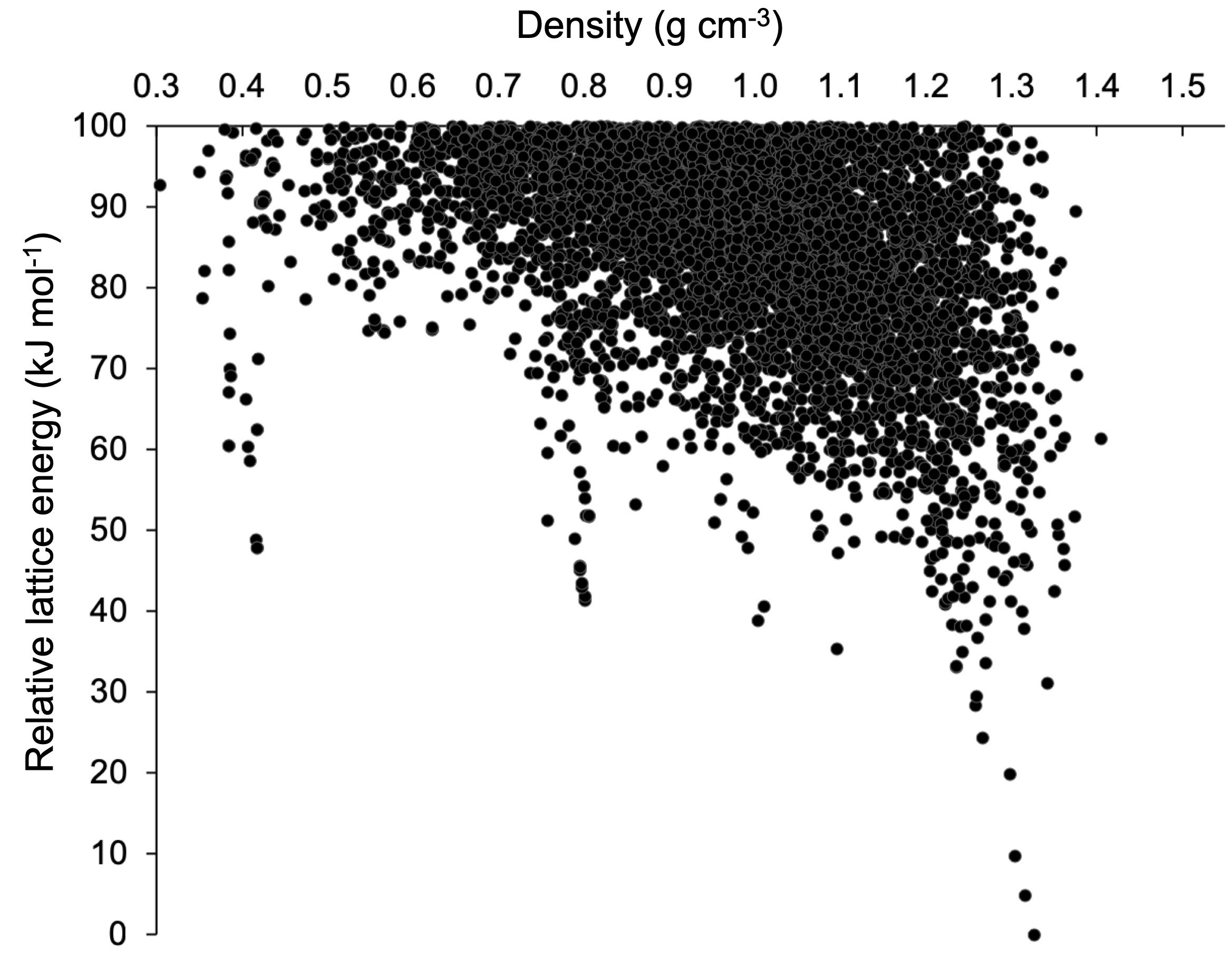

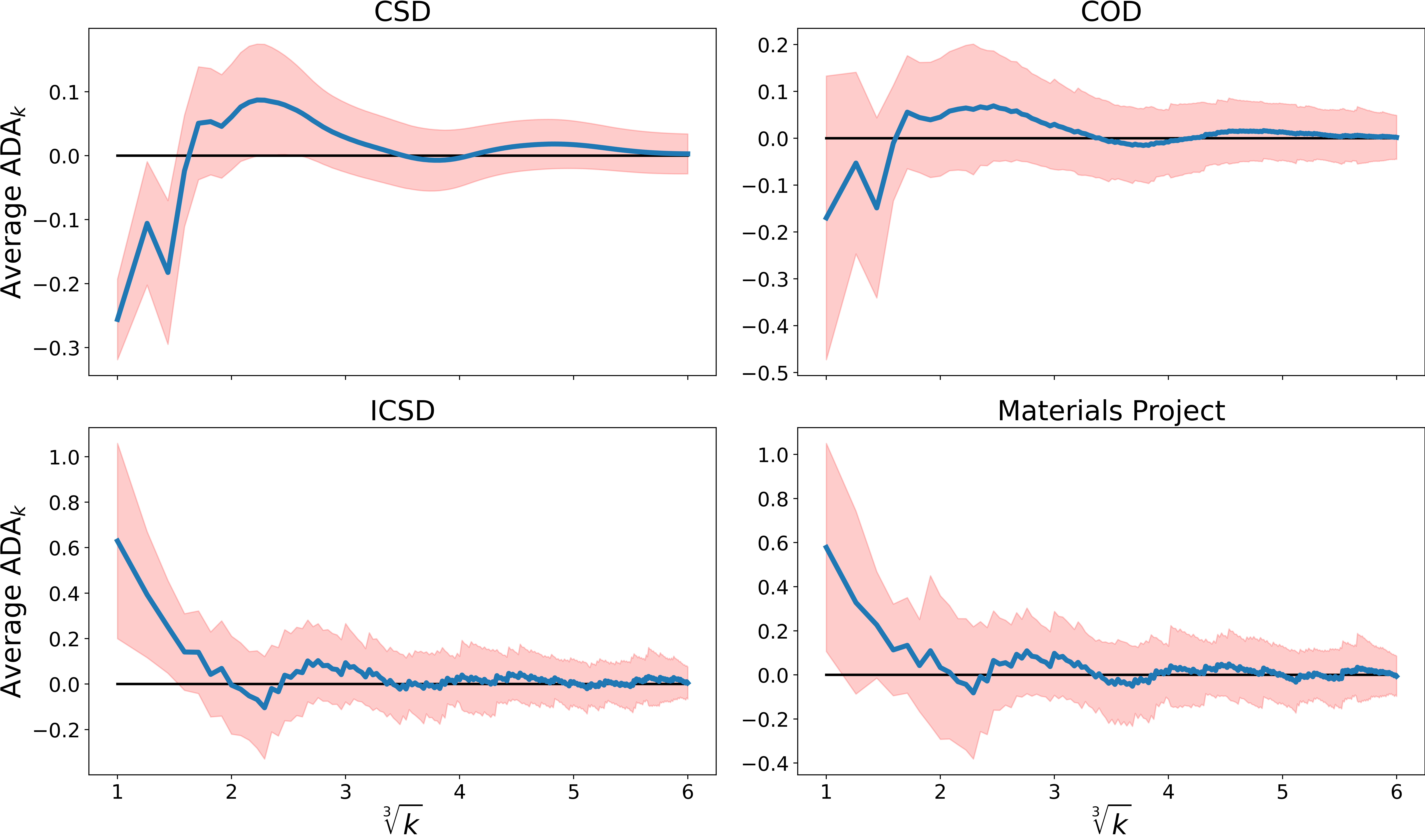

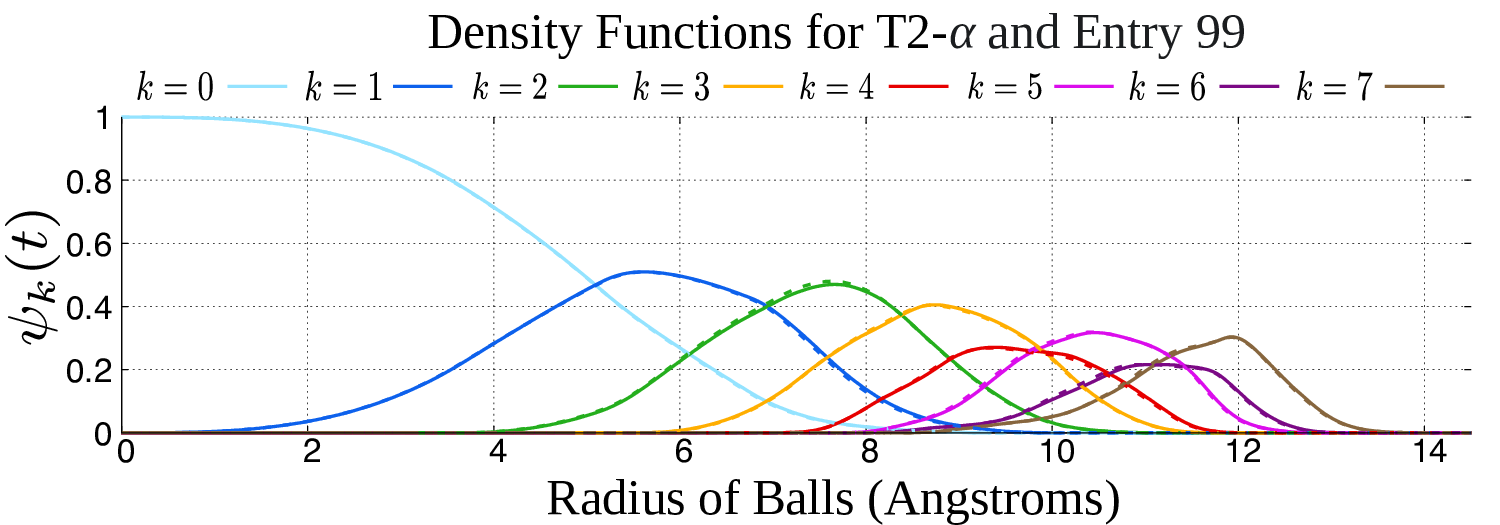

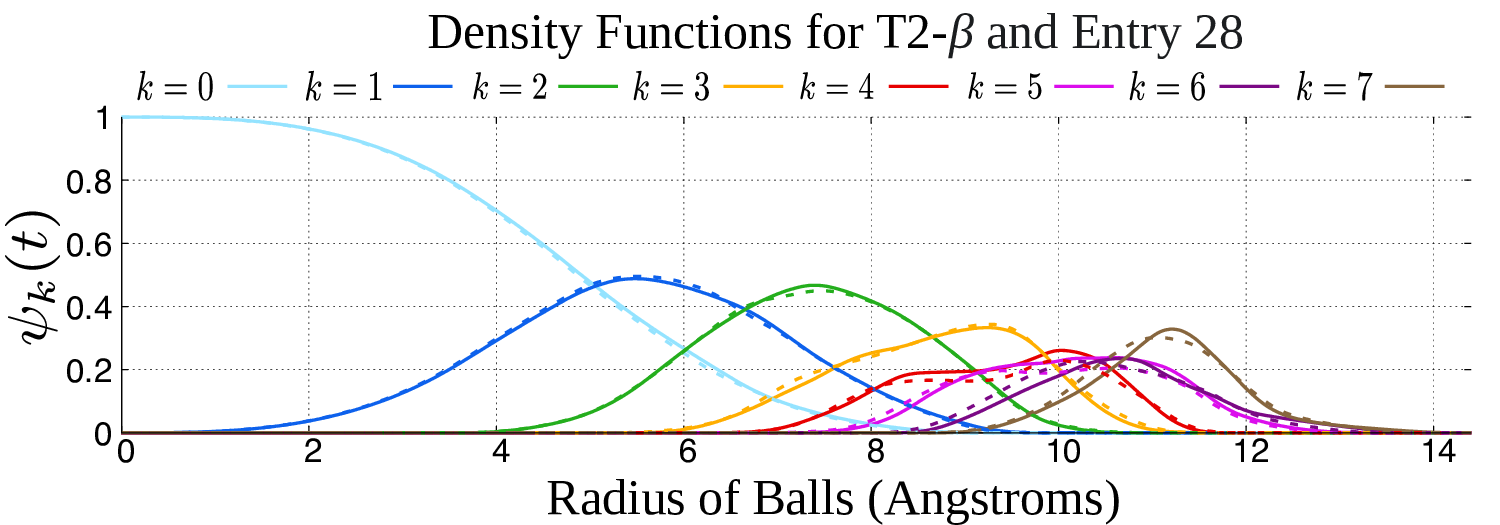

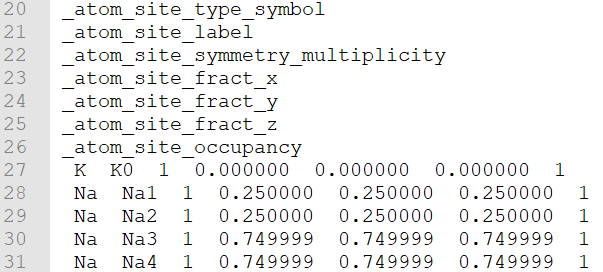

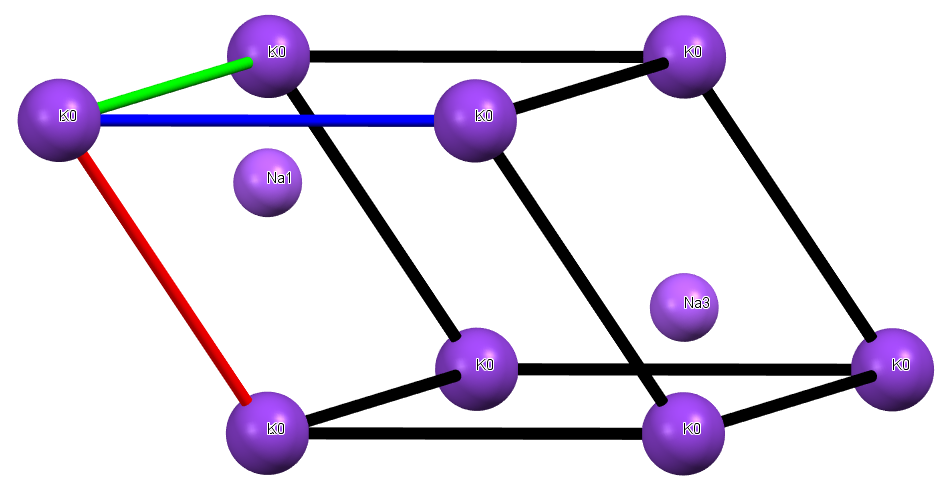

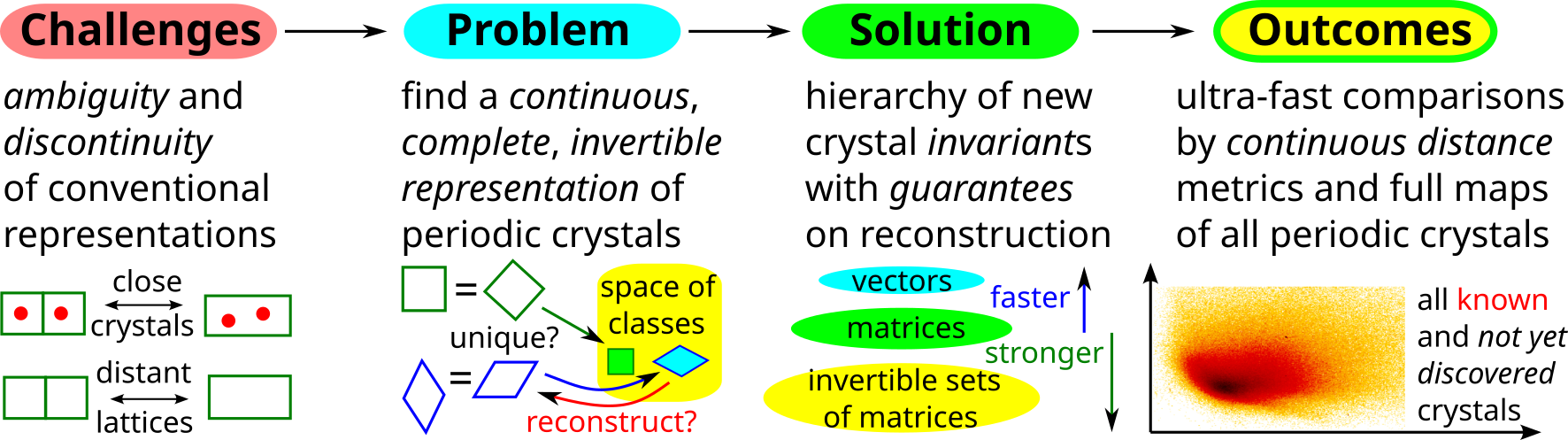

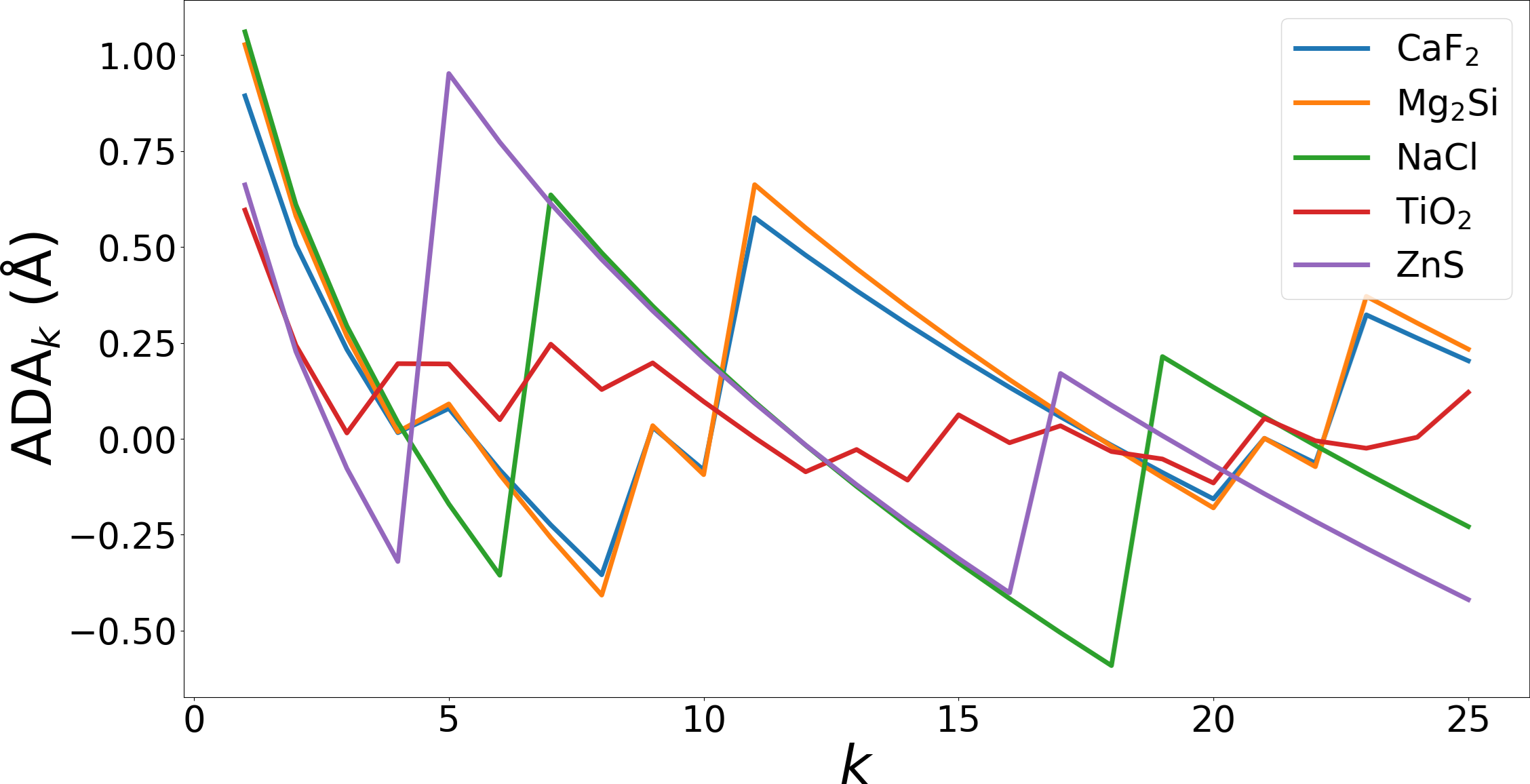

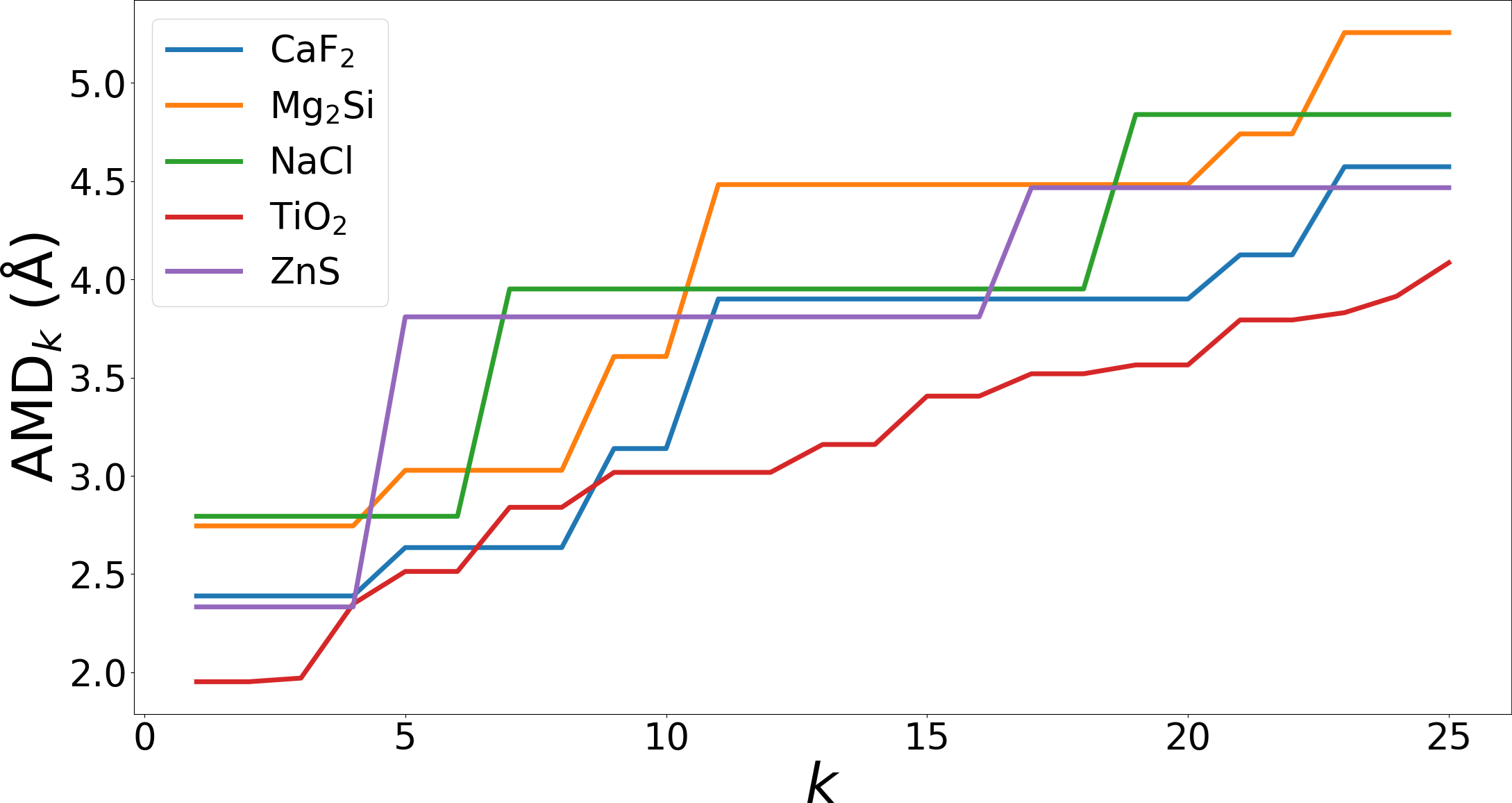

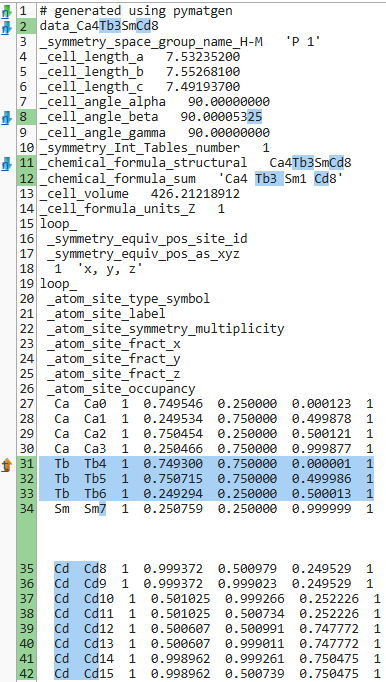

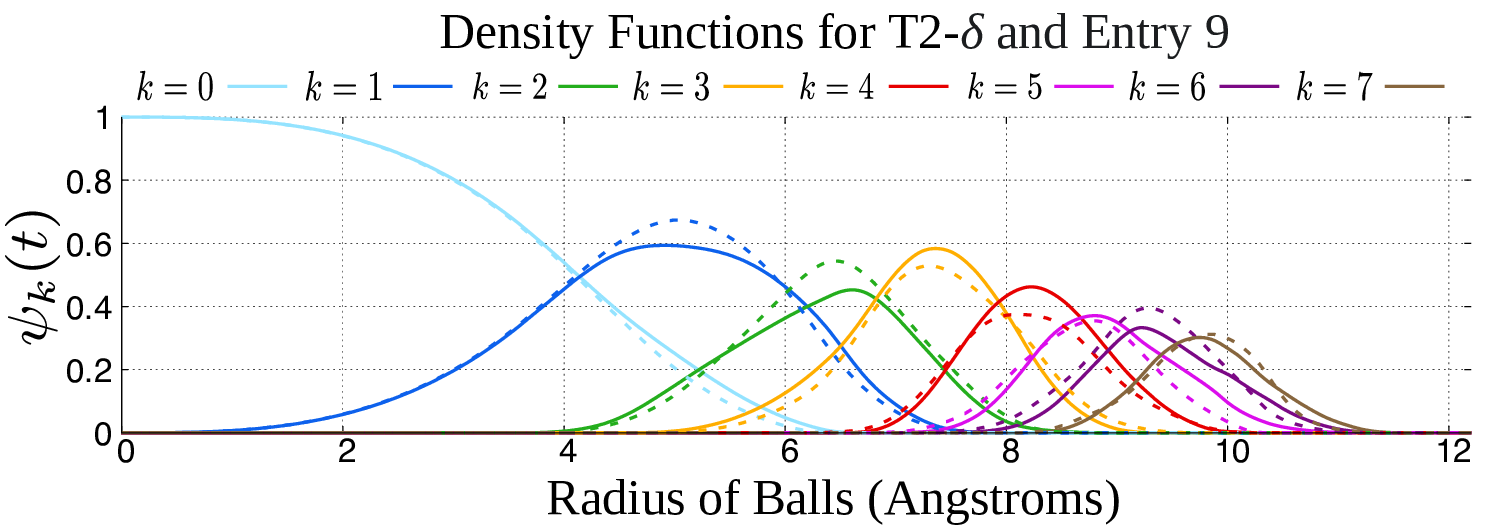

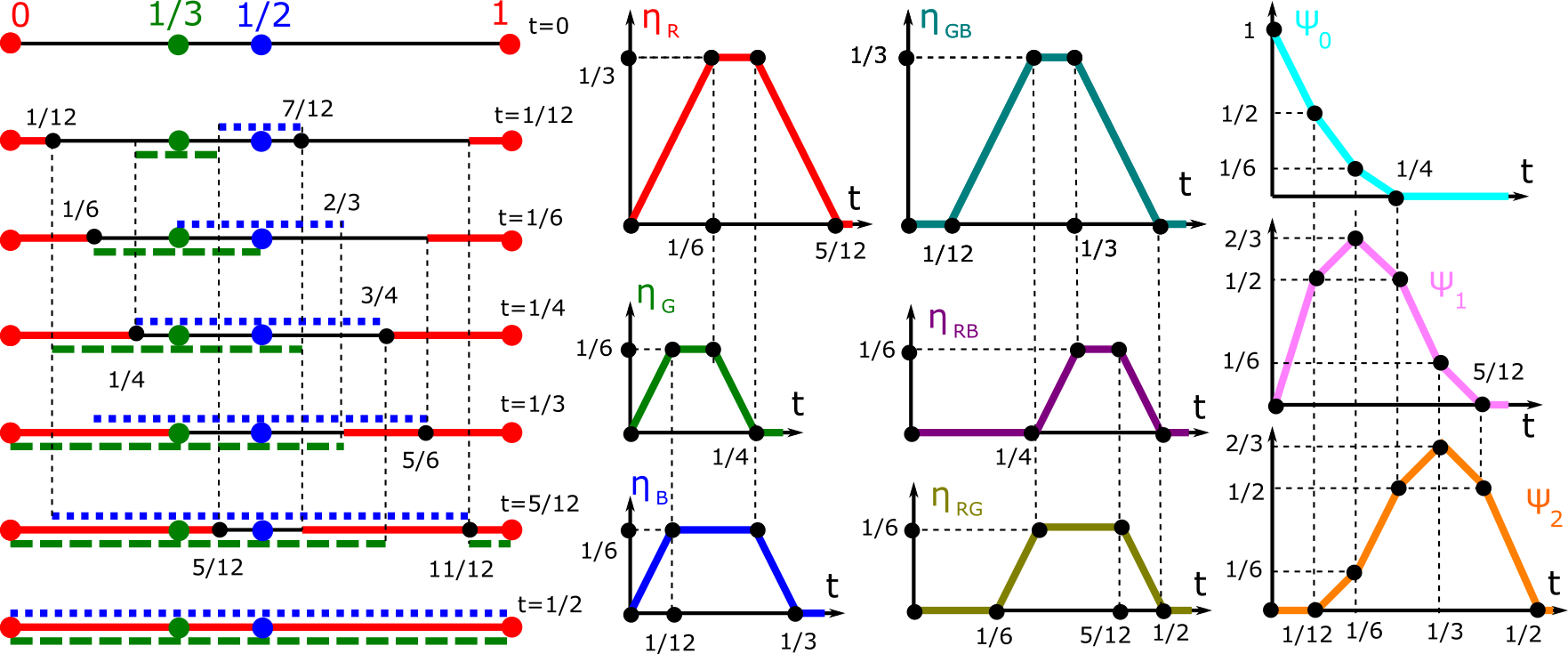

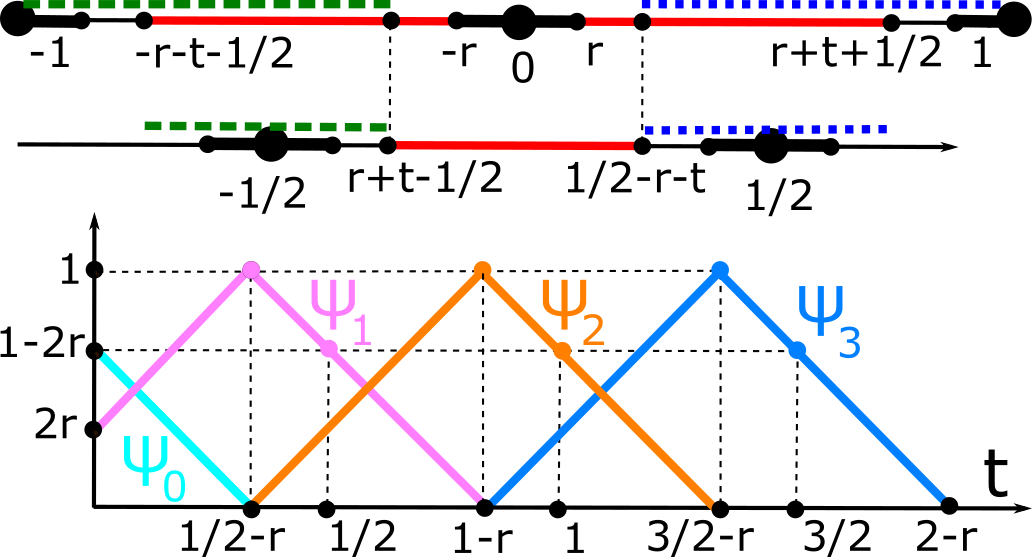

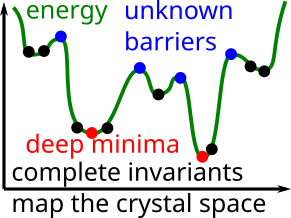

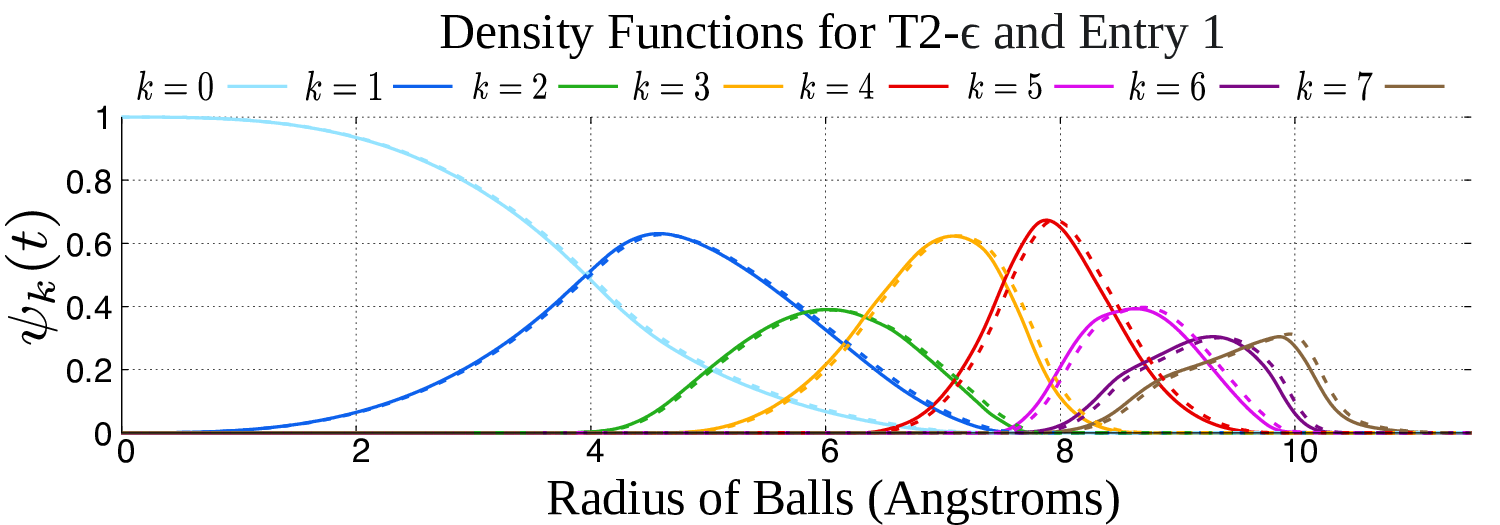

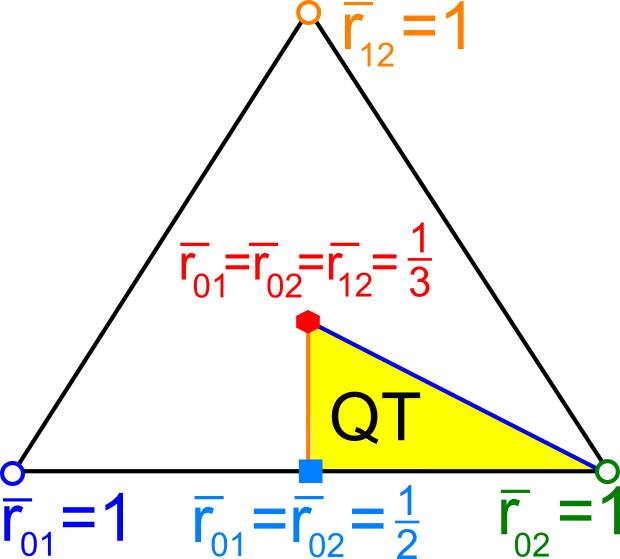

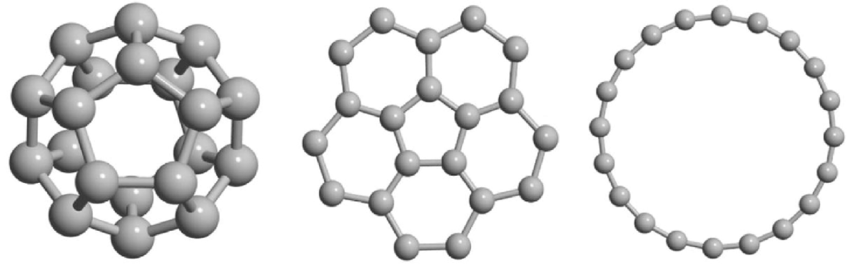

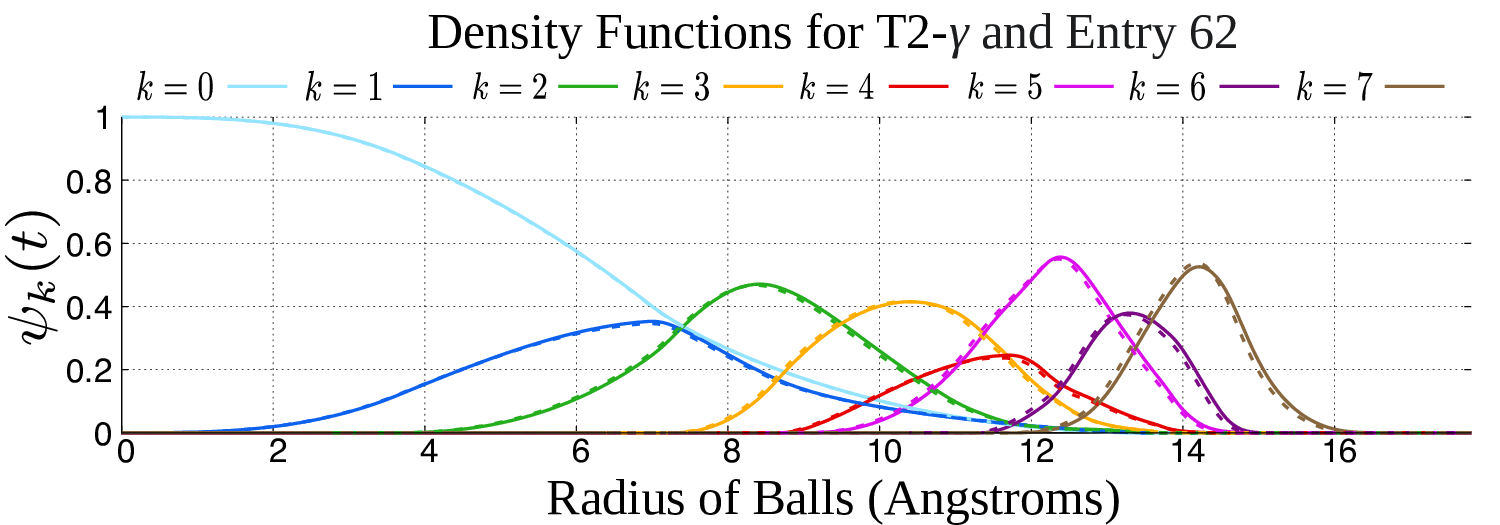

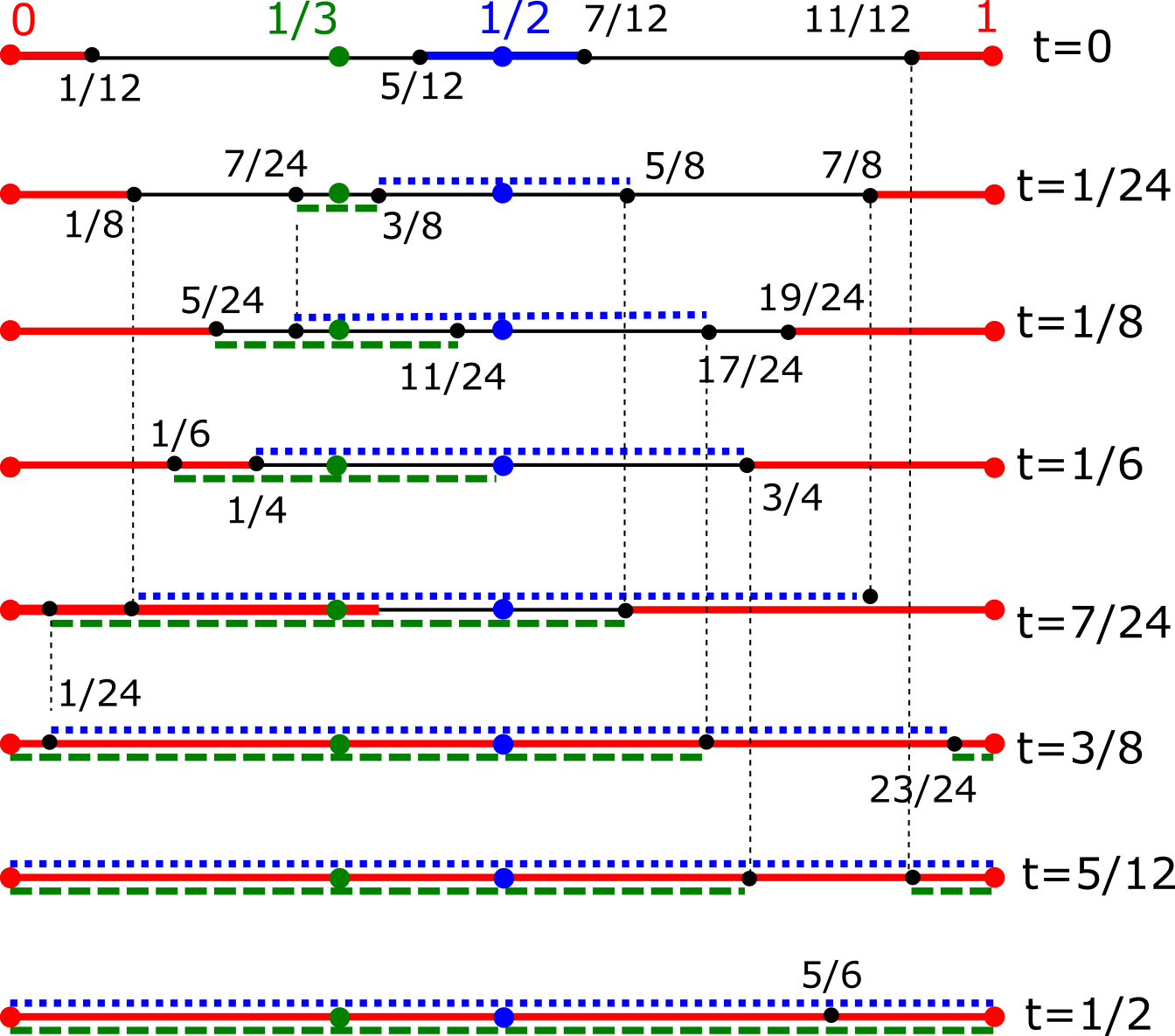

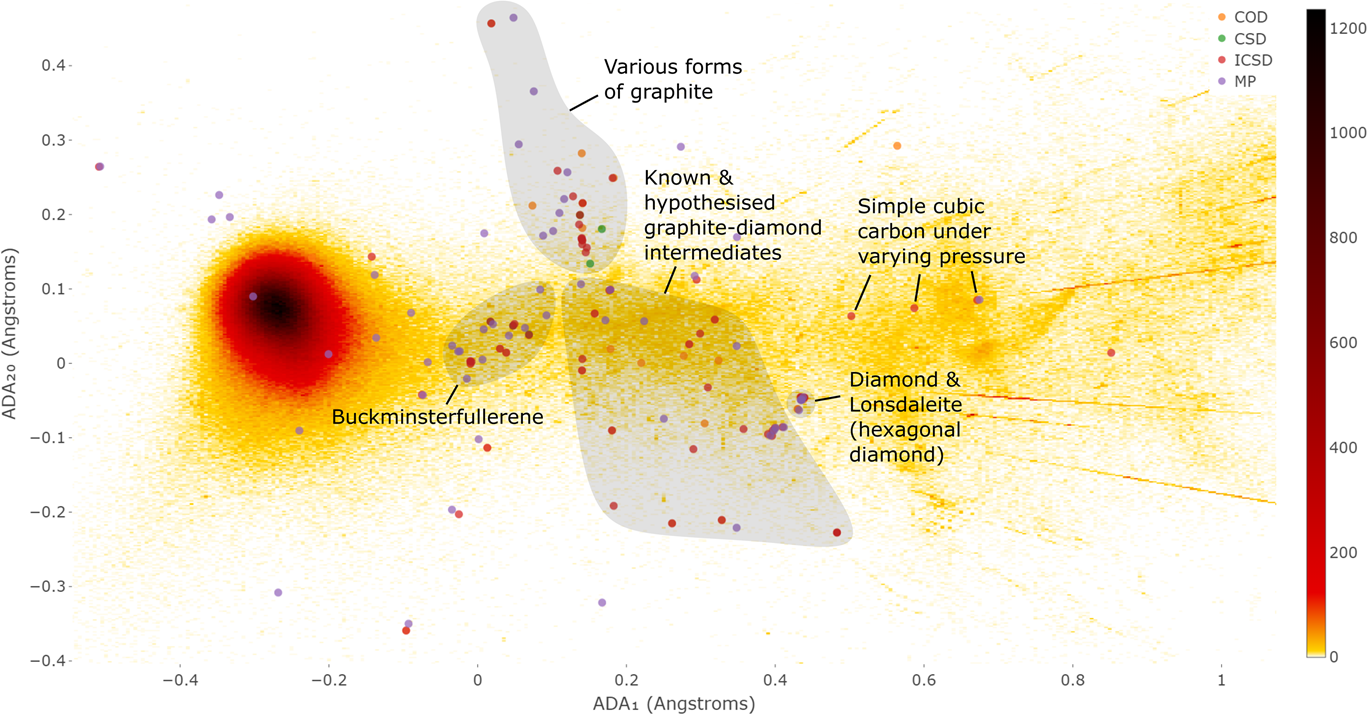

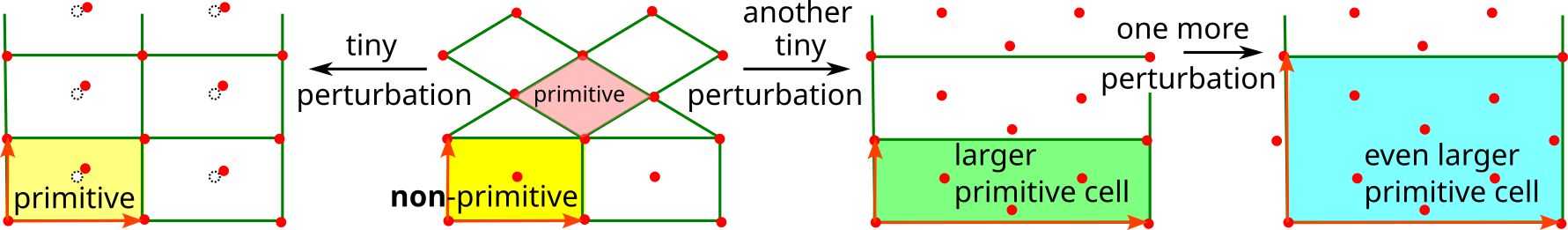

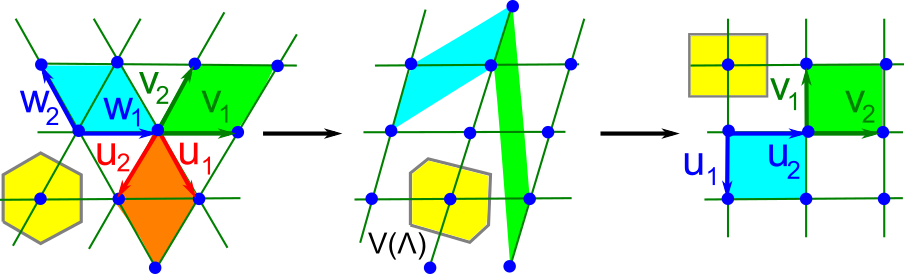

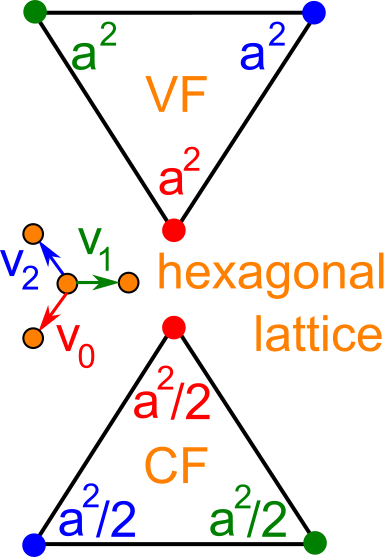

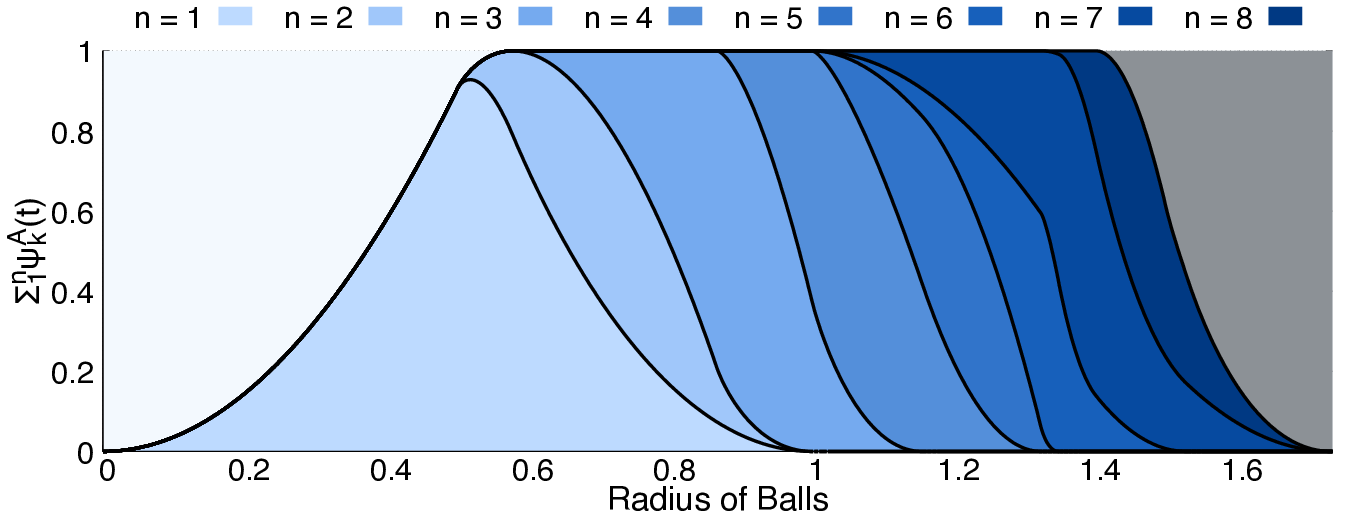

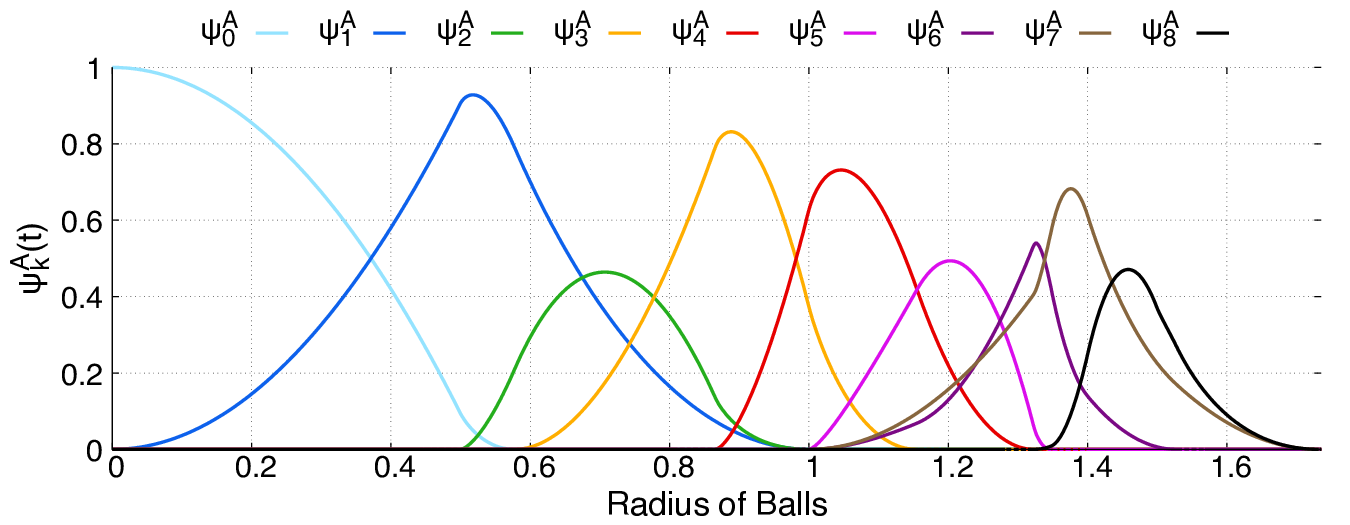

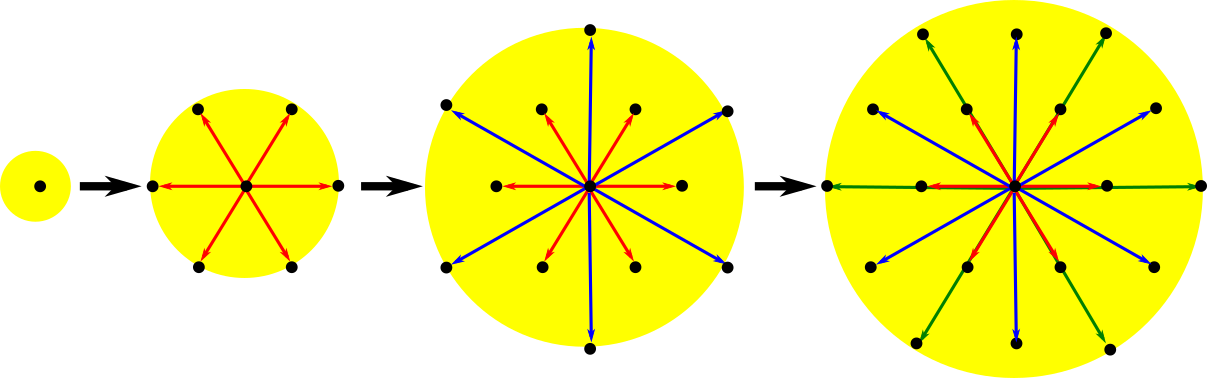

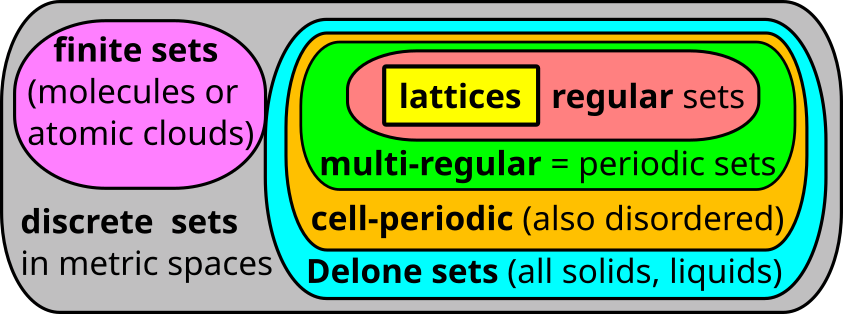

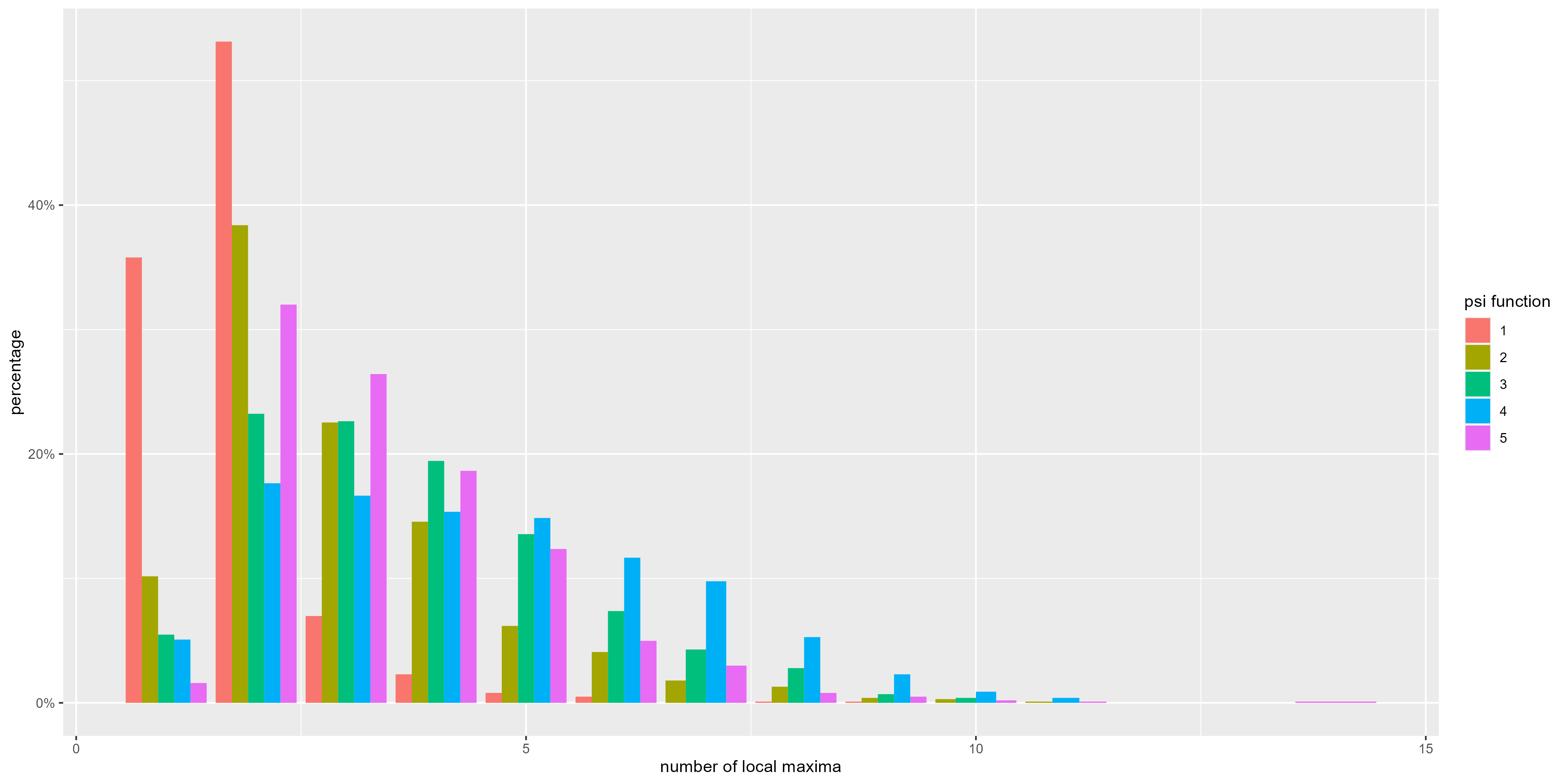

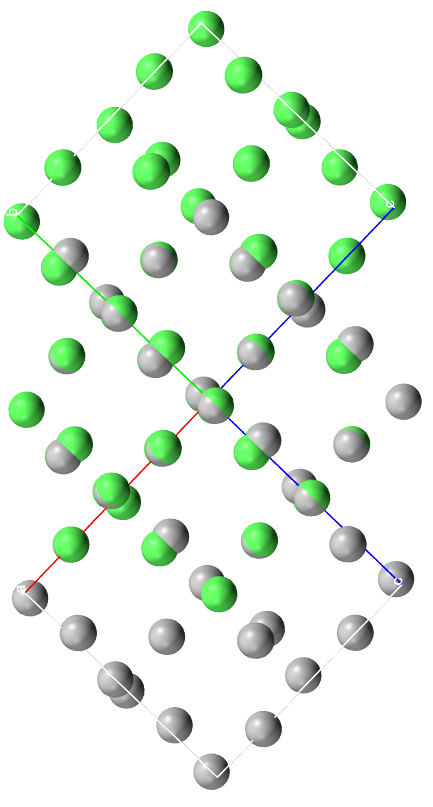

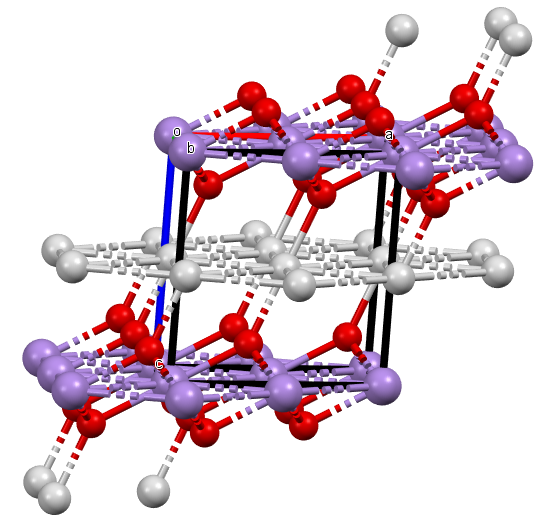

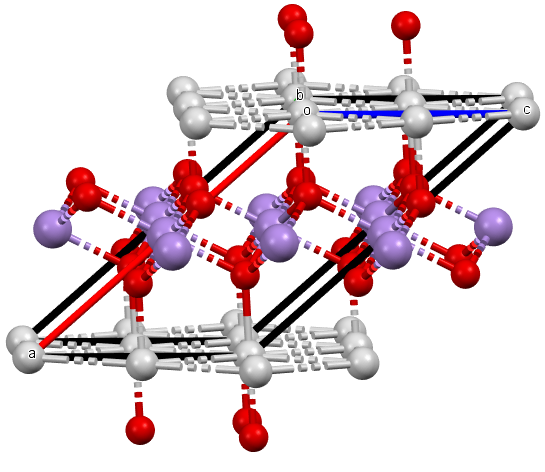

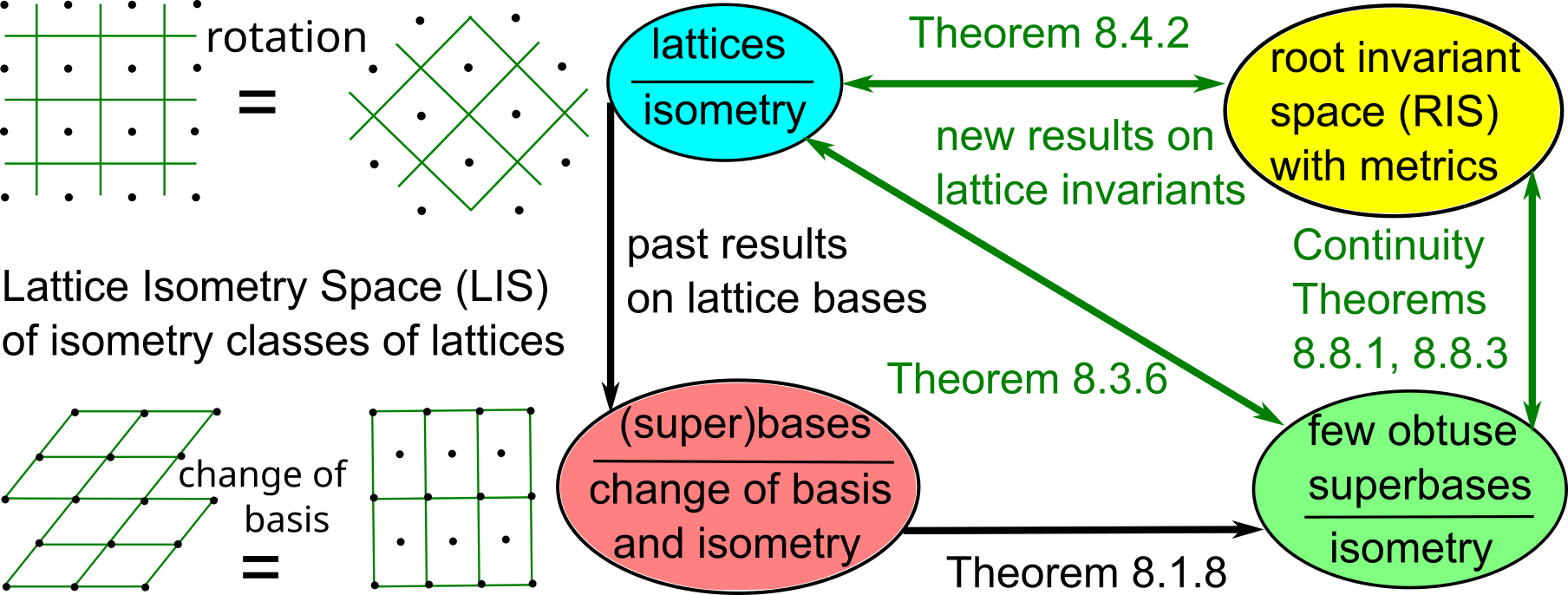

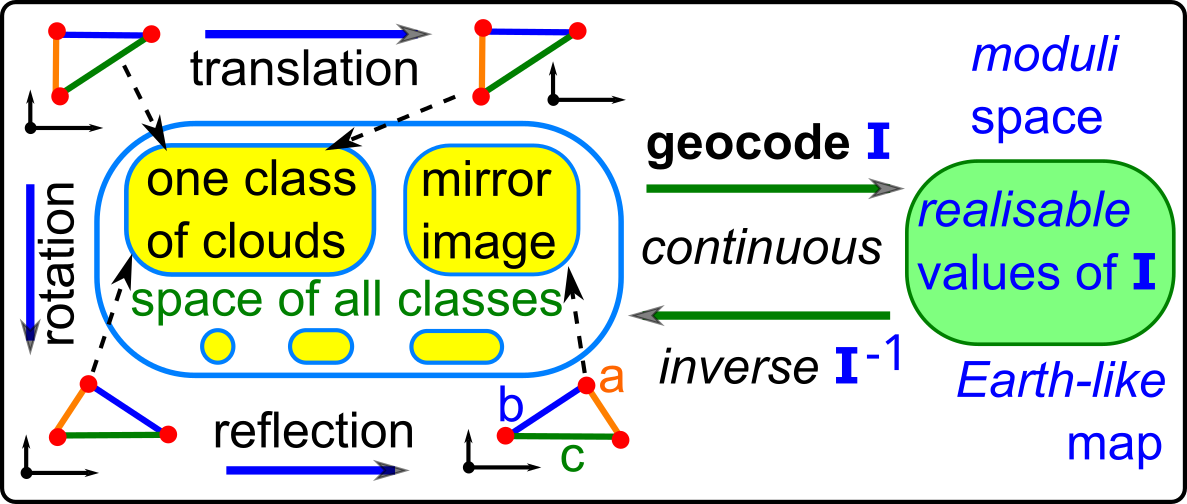

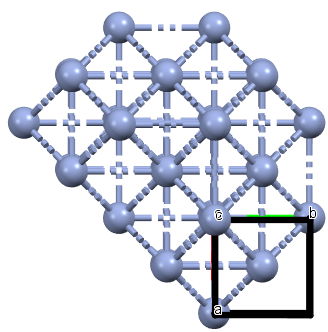

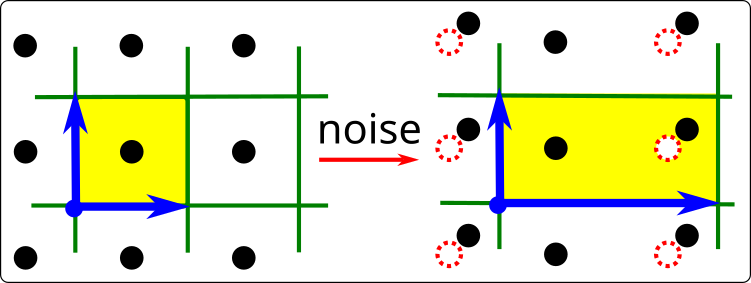

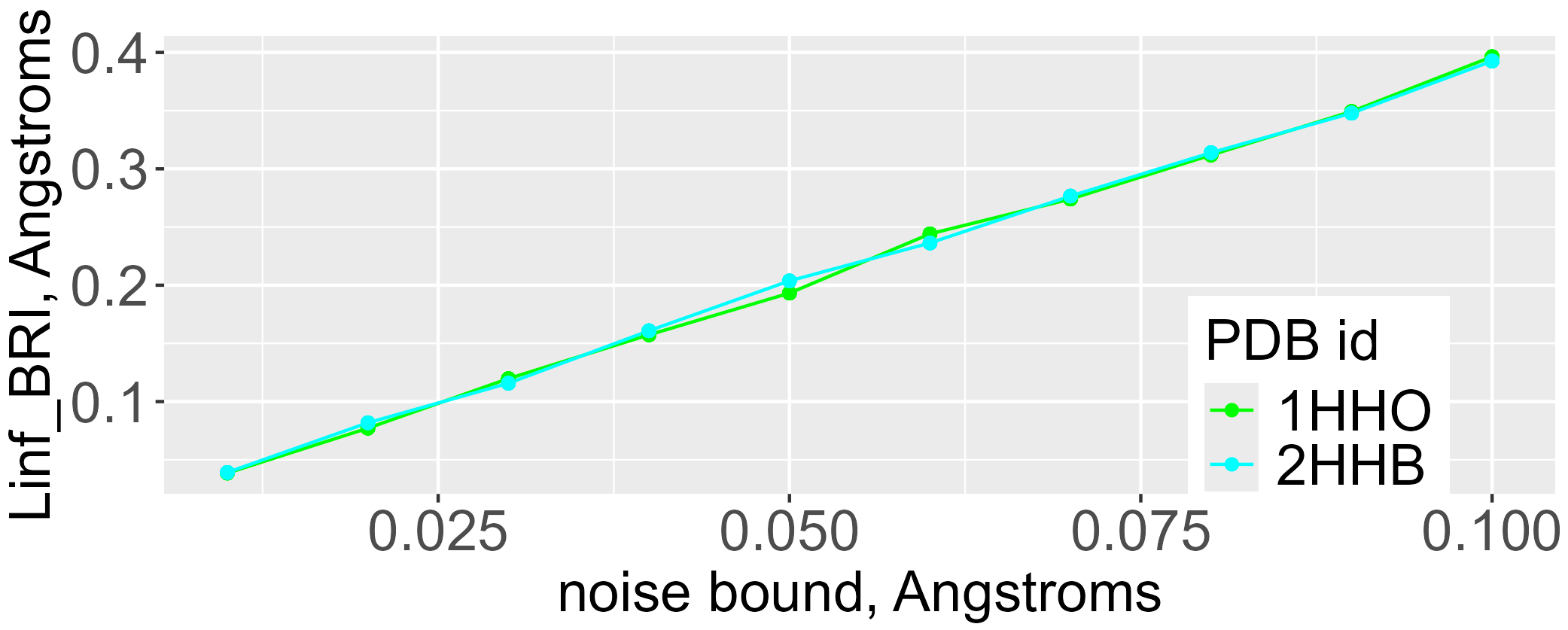

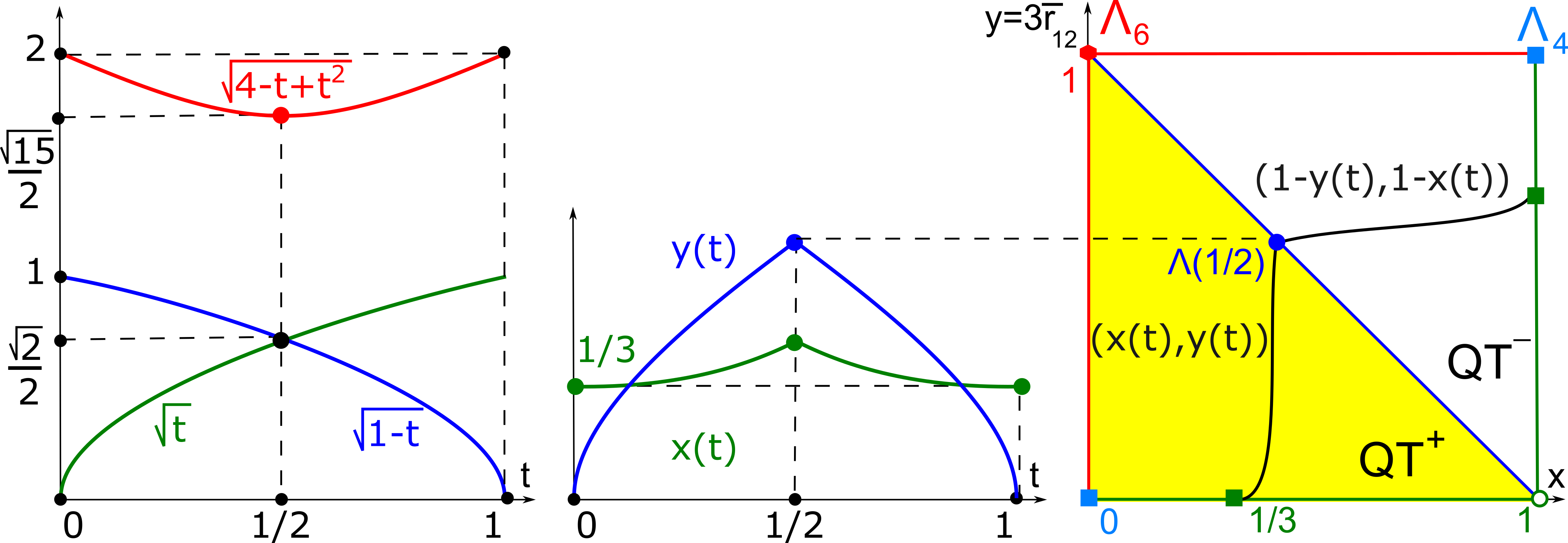

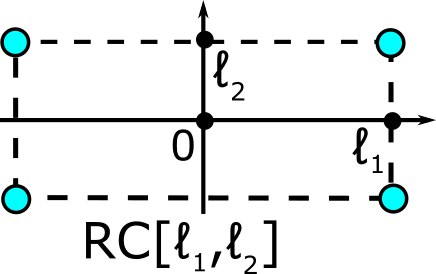

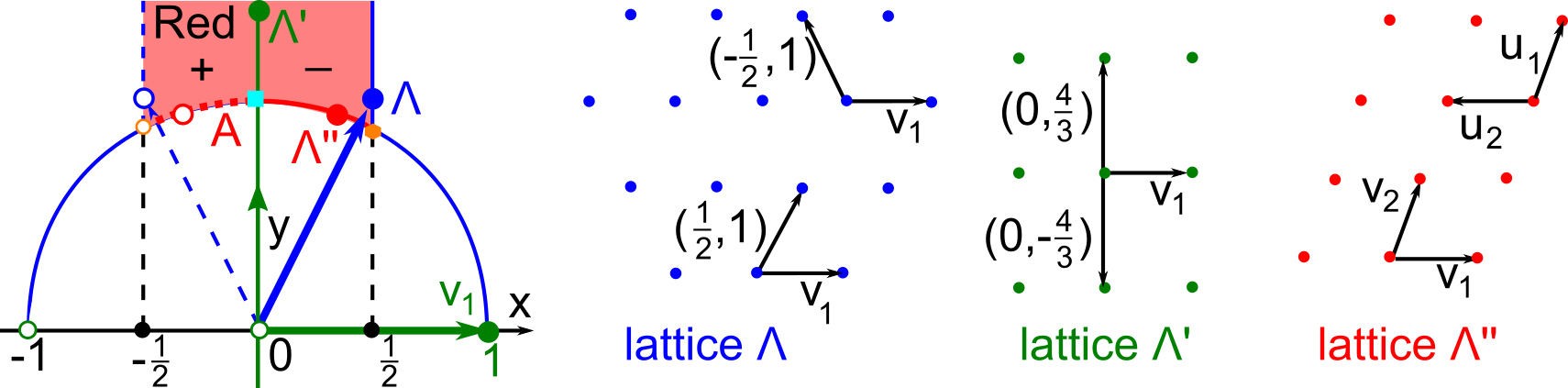

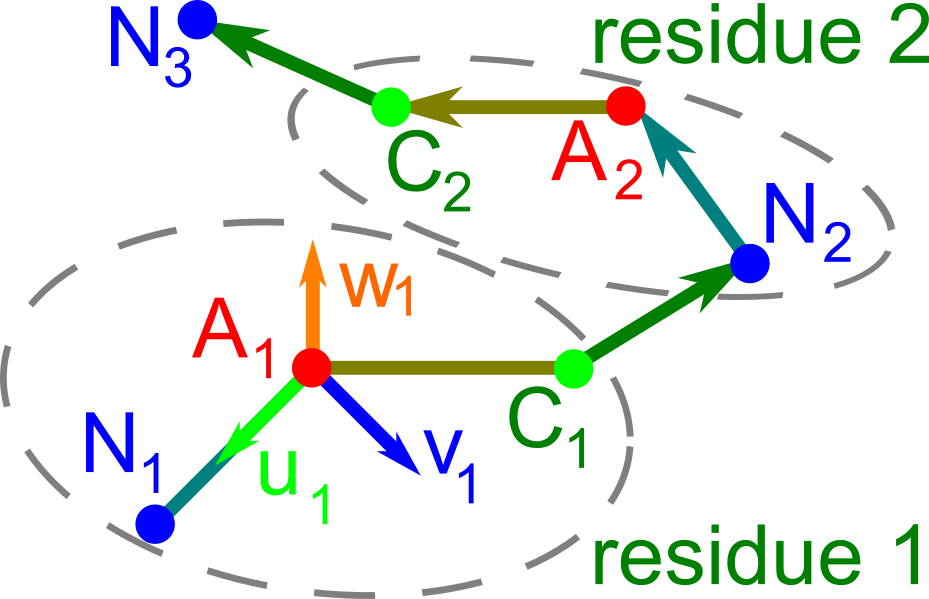

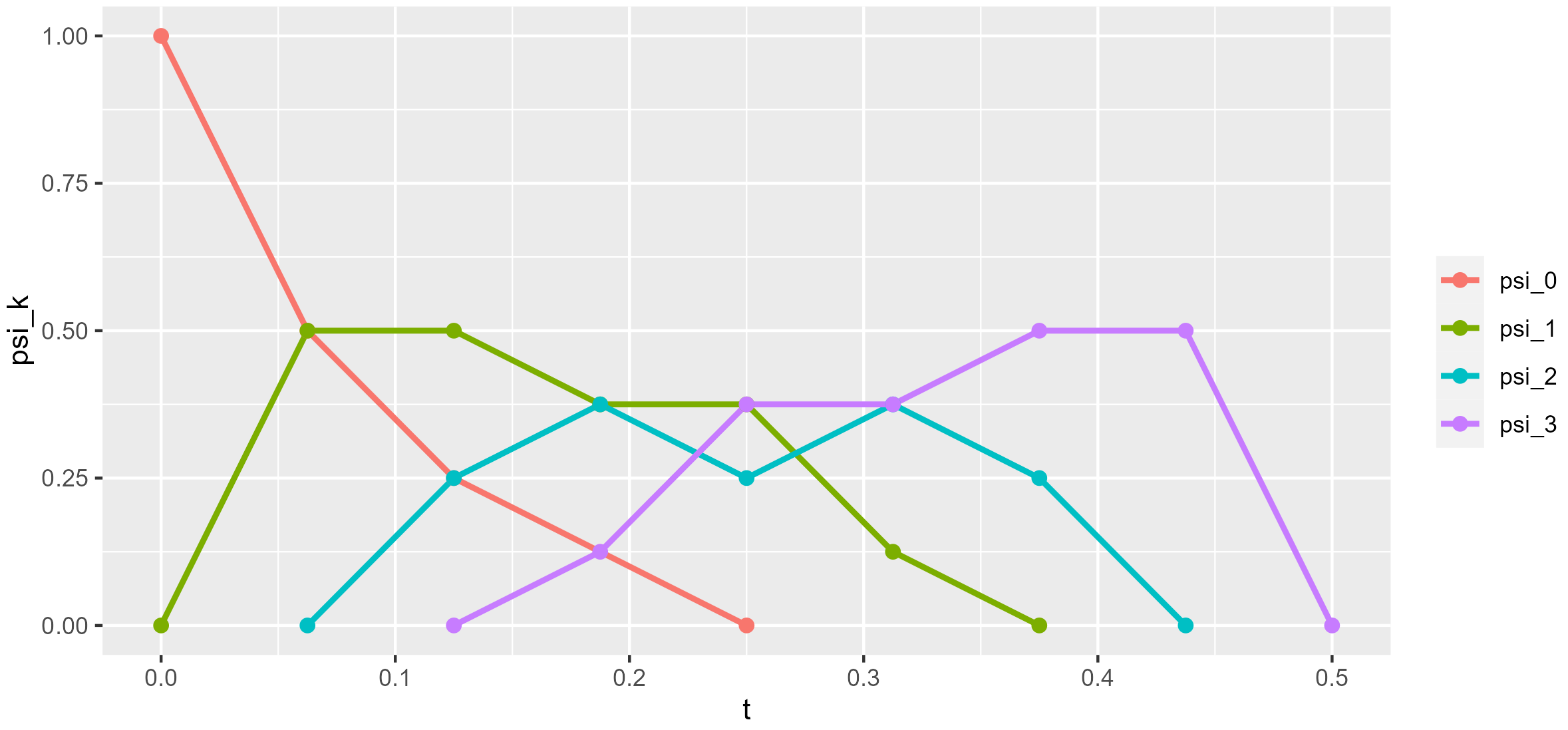

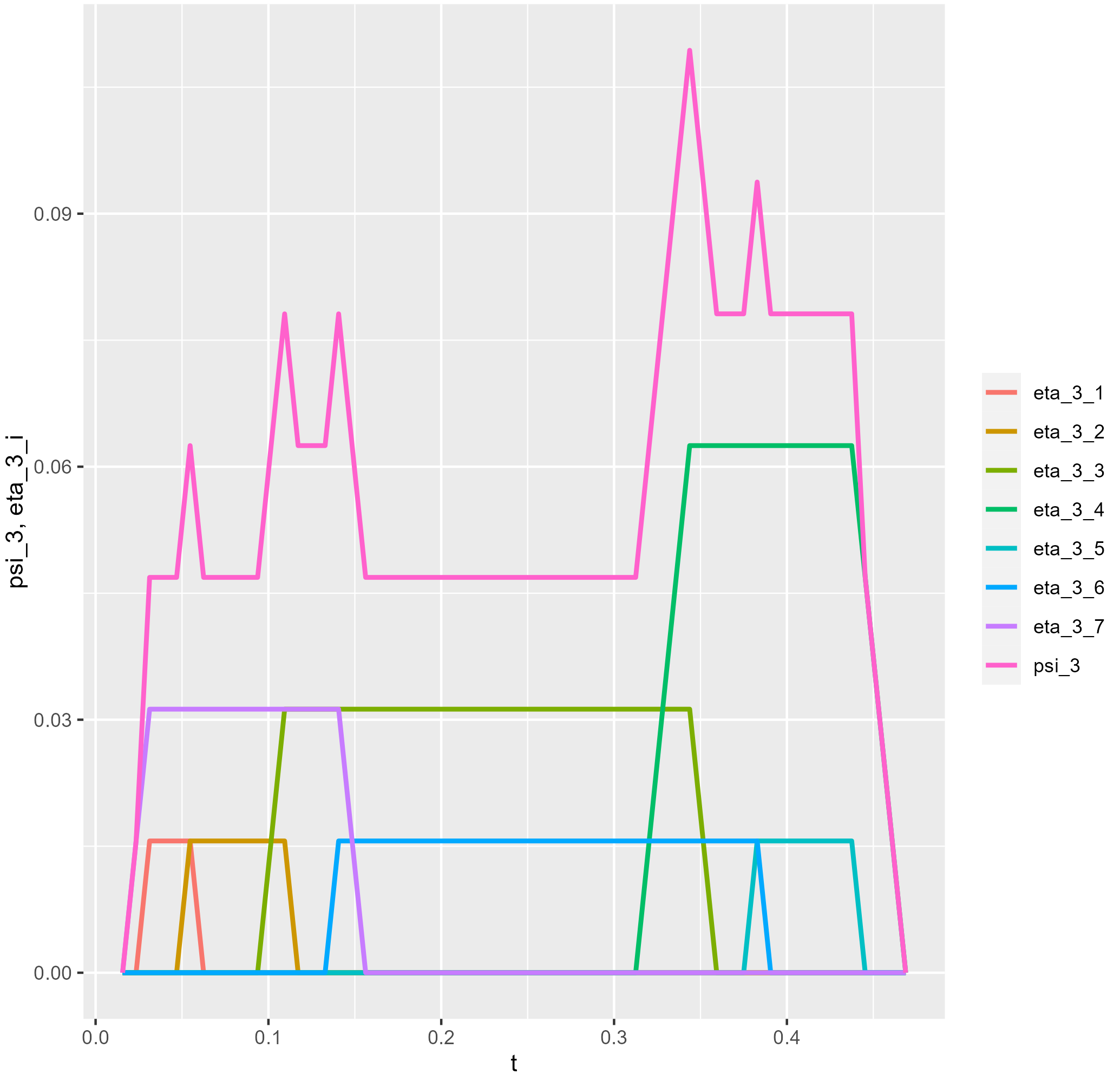

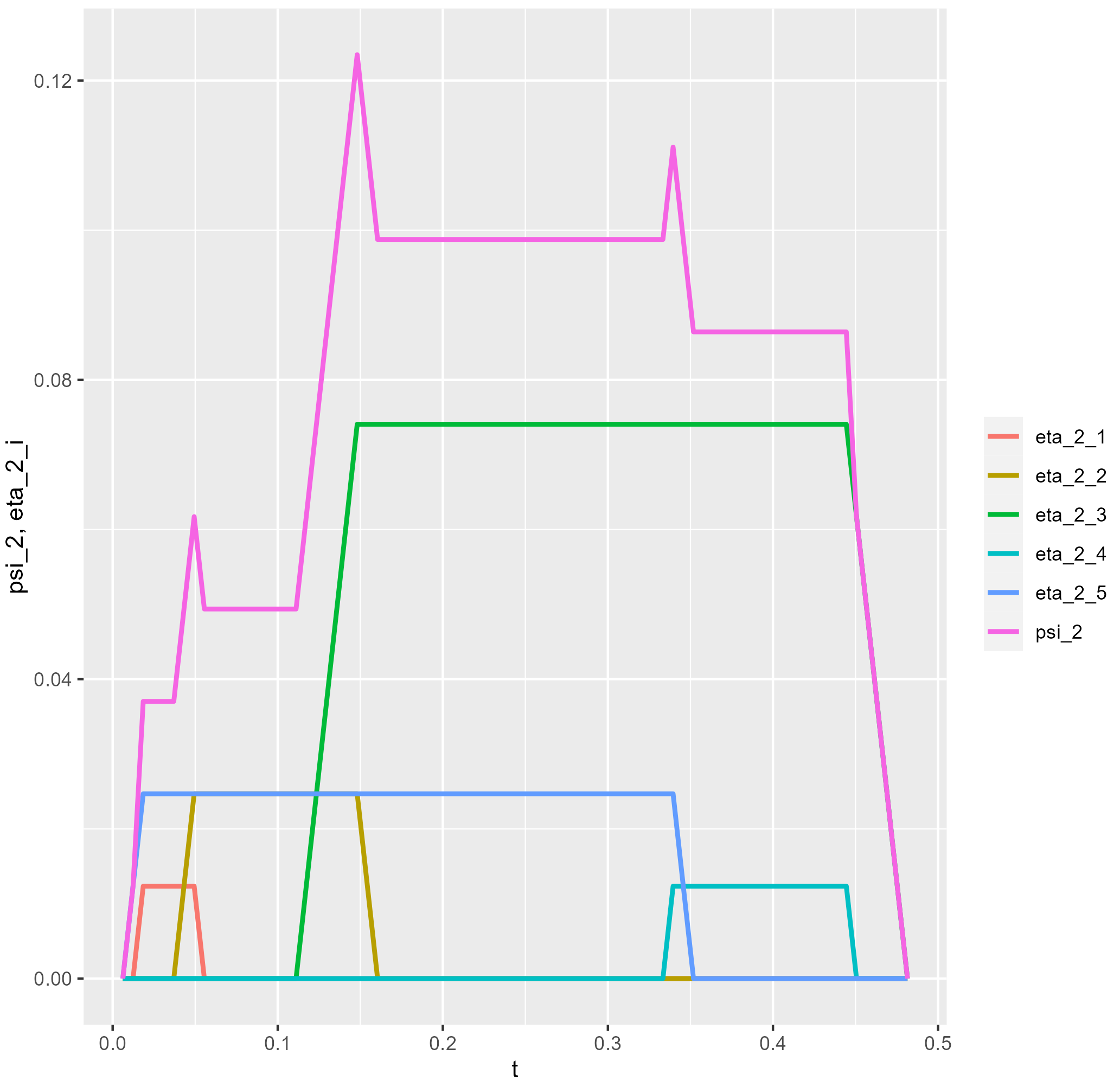

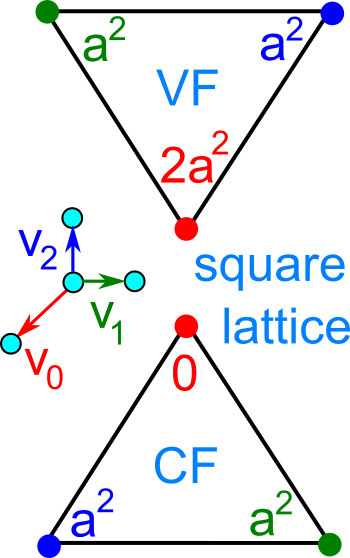

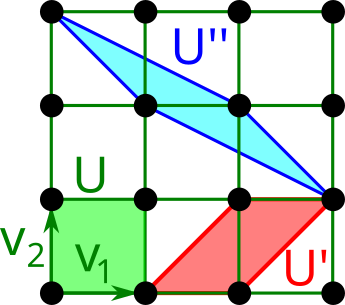

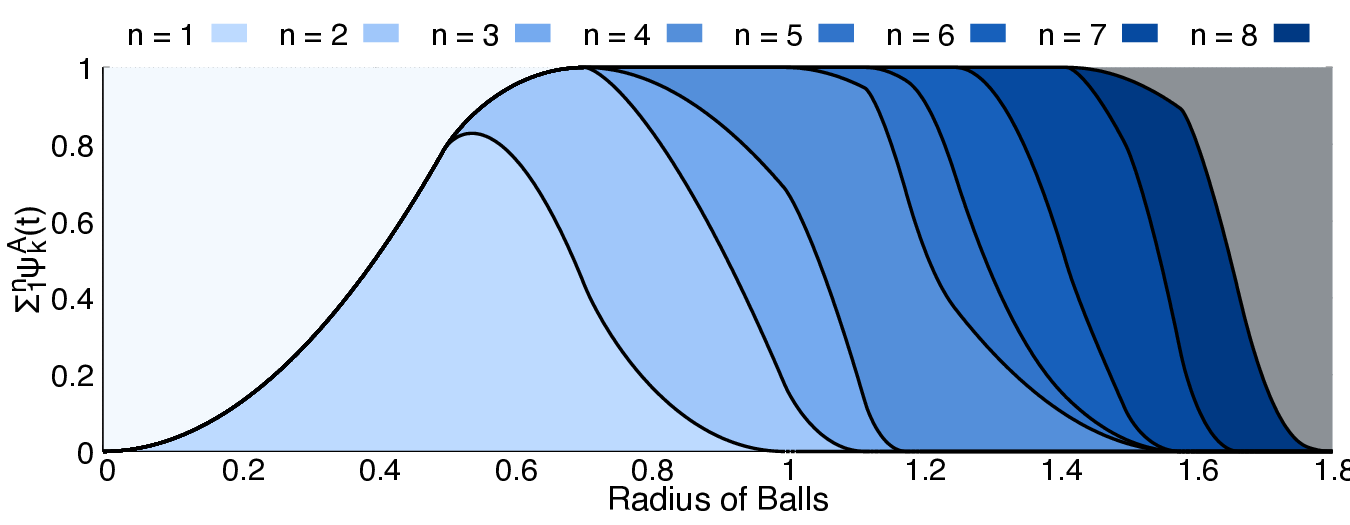

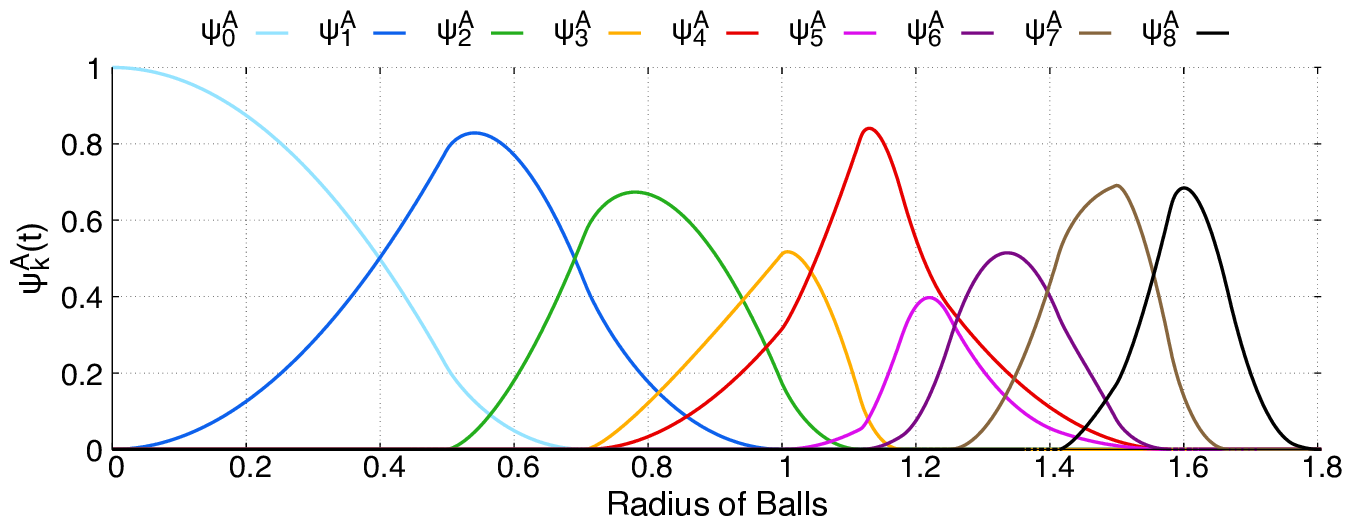

The second part of the book advances a similar classification in the much more difficult case of periodic point sets, which model all periodic crystals at the atomic scale. The most significant result is the hierarchy of invariants from the ultra-fast to complete ones. The key challenge was to resolve the discontinuity of crystal representations that break down under almost any noise. Experimental validation on all major materials databases confirmed the Crystal Isometry Principle: any real periodic crystal has a unique location in a common moduli space of all periodic structures under rigid motion. The resulting moduli space contains all known and not yet discovered periodic crystals and hence continuously extends Mendeleev's table to the full crystal universe.

Where there is Matter, there is Geometry -Johannes Kepler a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution.

This book introduces the new research area of Geometric Data Science, where data can represent any real objects through geometric measurements. Some of the simplest inputs of real data objects are finite and periodic sets of unordered points.

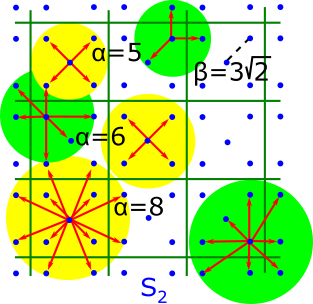

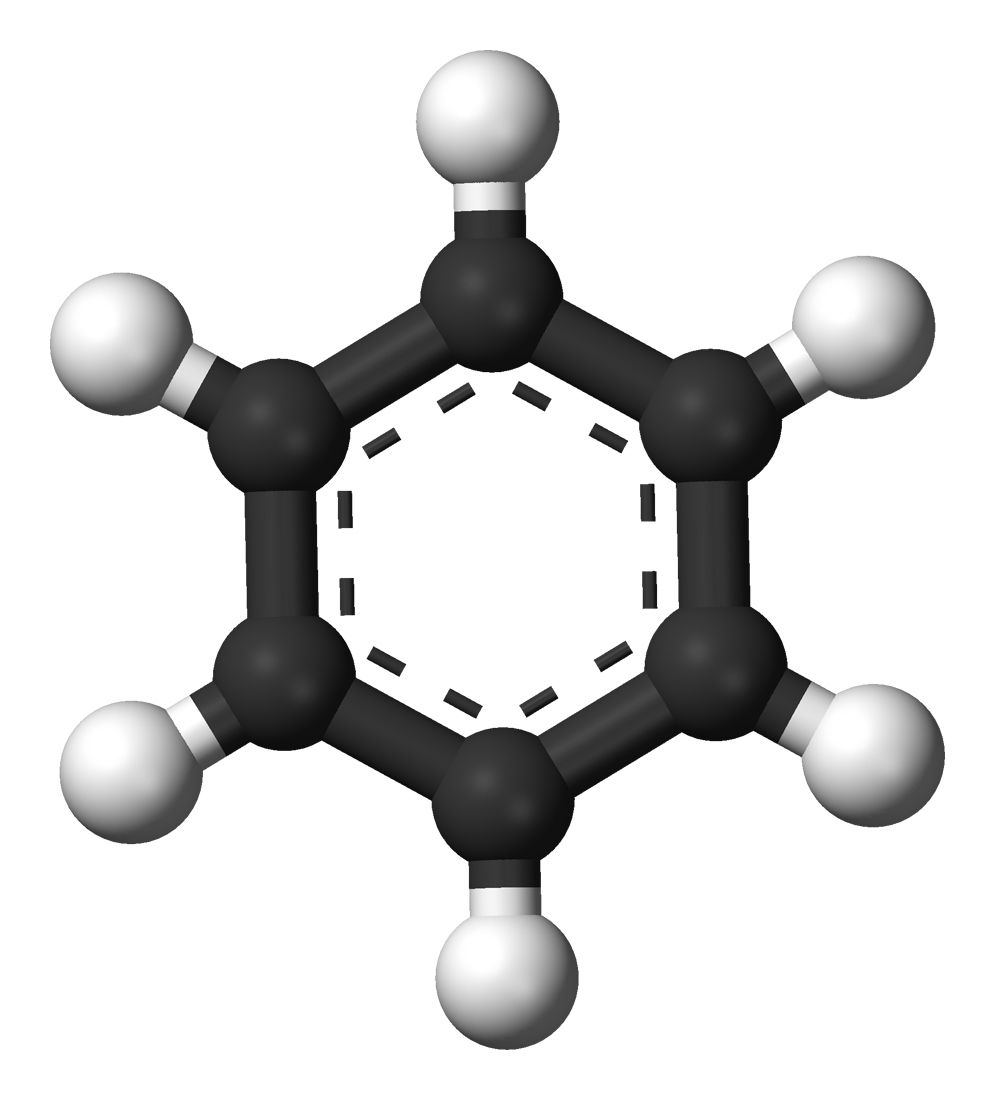

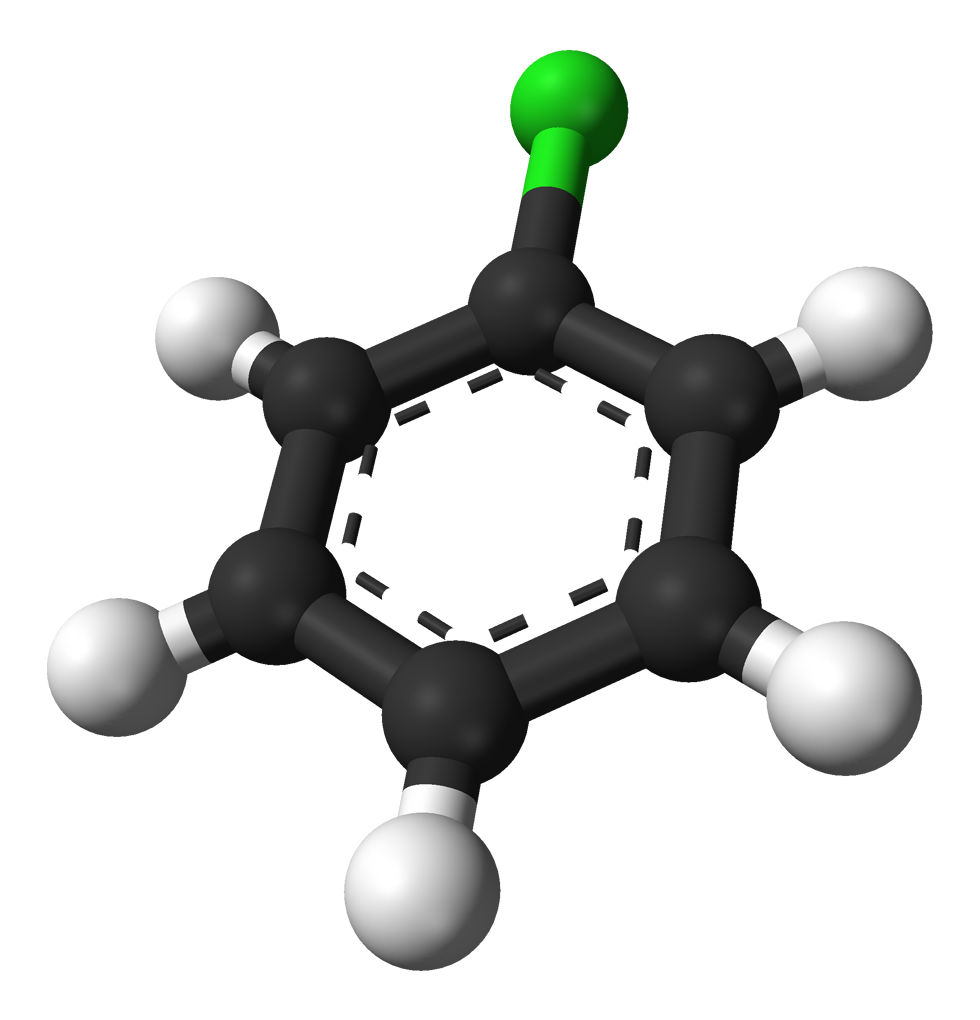

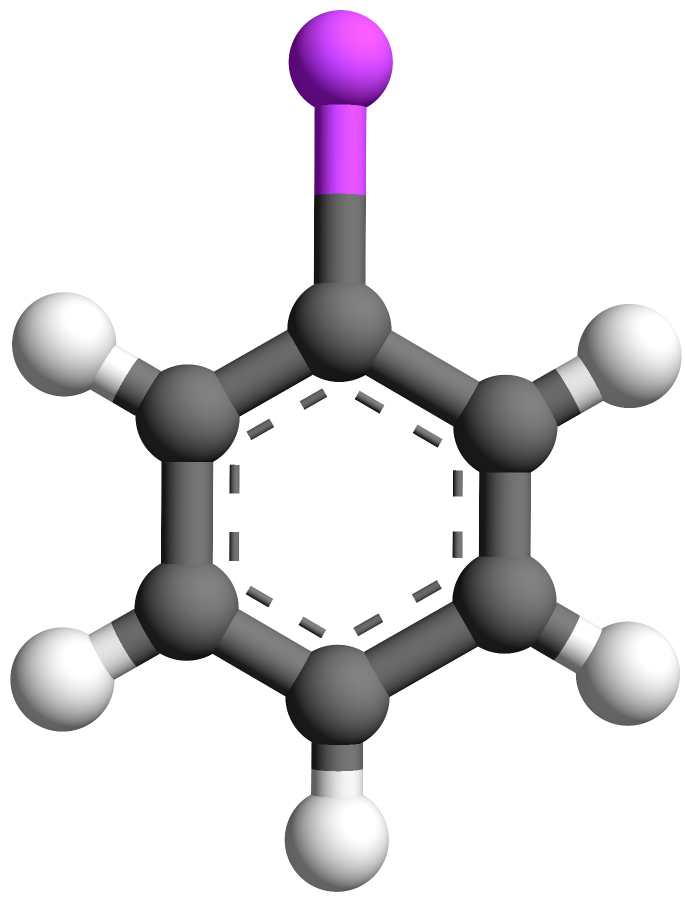

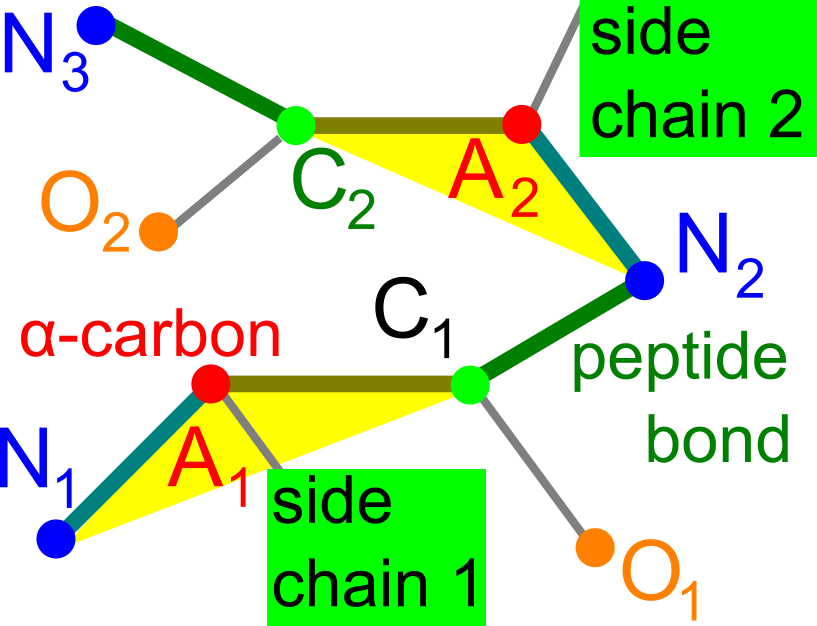

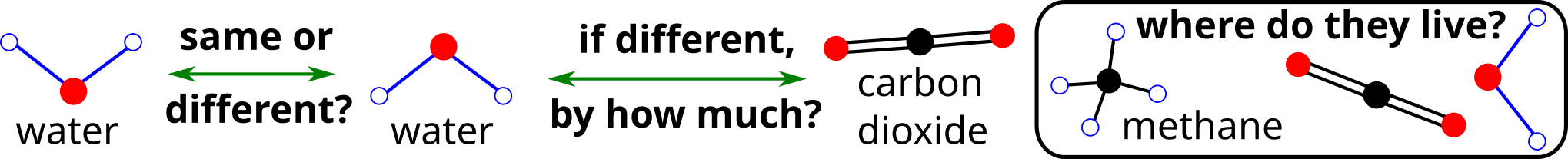

For example, a molecule can be fully described by the positions of its atoms in a 3-dimensional space. However, many descriptions are highly ambiguous, especially to a computer, which operates only with numbers. For example, a photograph is ambiguous, because any object can have an astronomically large number of photographs.

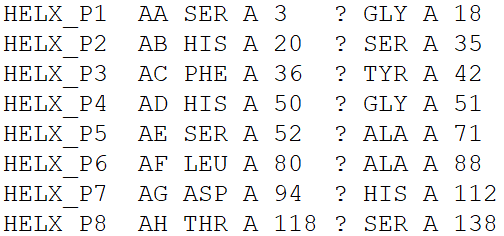

All attempts to standardise photographs, as in passports, have shifted towards more reliable biometric data. Indeed, the identification of living organisms was dramatically improved due to the discovery of a DNA structure. However, geometric structures remained ambiguous for many objects, including proteins and materials, which are still represented by photograph-style inputs depending on arbitrary coordinate systems.

The major obstacle to progress from trial-and-error in chemistry and biology to a justified design of materials and drugs was the absence of rigorous definitions and problem statements. Geometric Data Science fills this gap by developing foundations based on equivalences, invariants, distance metrics, and polynomial-time algorithms.

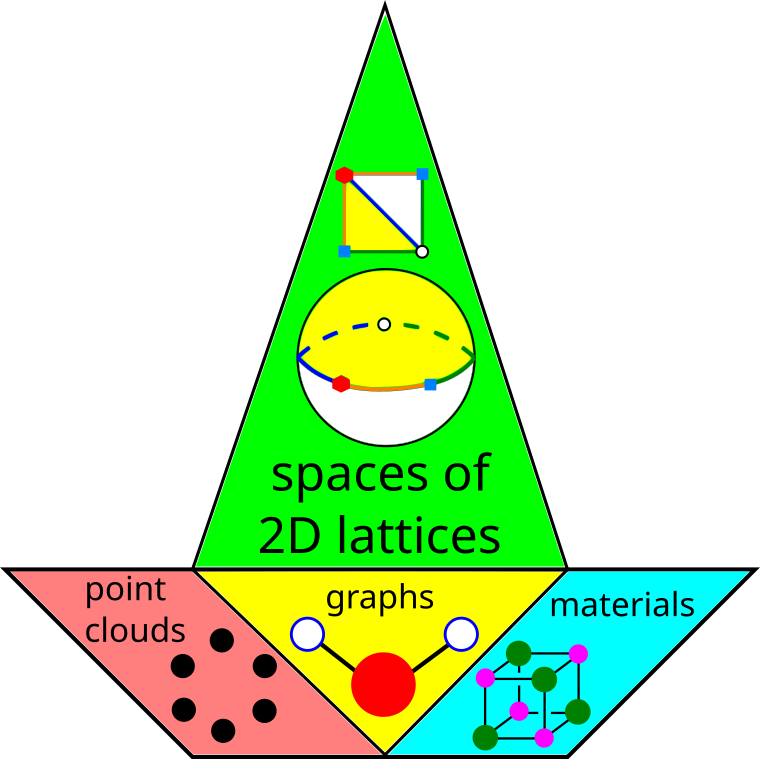

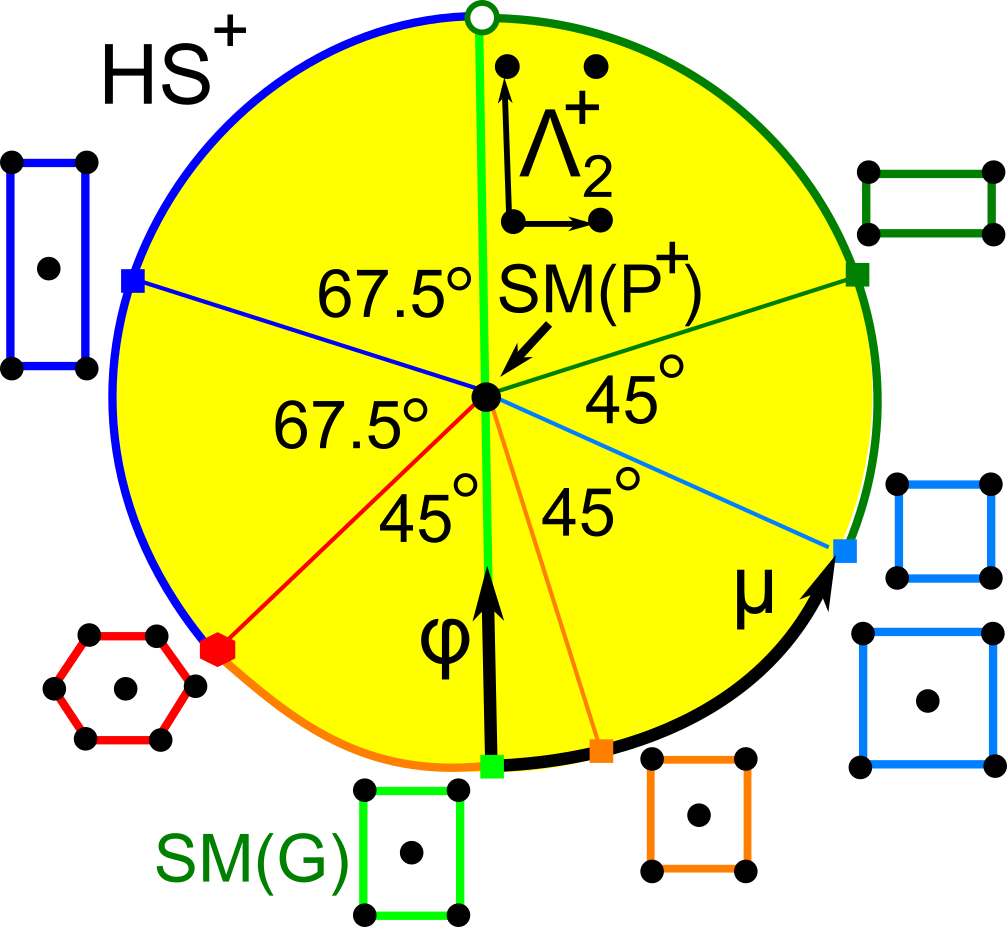

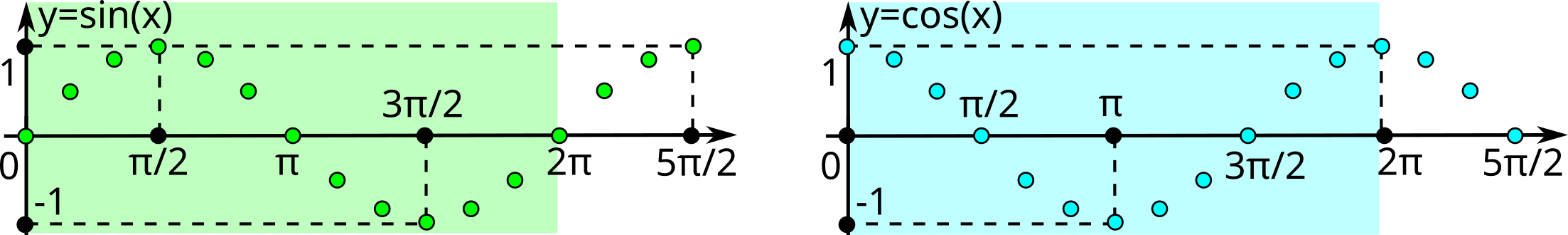

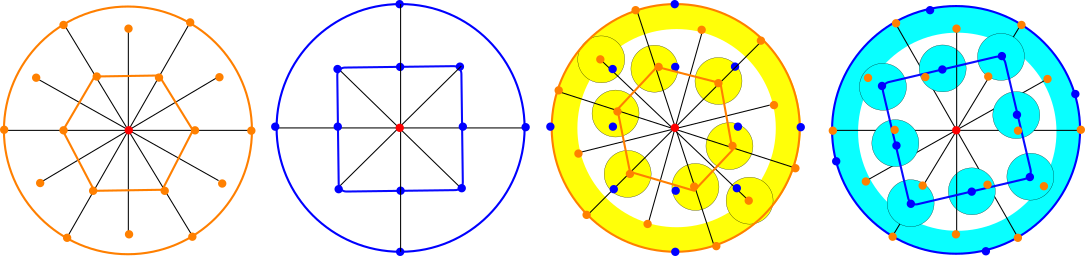

The main geo-mapping problem is to analytically describe moduli spaces of geometric structures that are classes of data objects modulo an equivalence relation. These moduli spaces are prototypes of ’treasure maps’ containing all known objects of a certain type as well as all not yet discovered ones. A discrete example is Mendeleev’s table of chemical elements, which was initially half-empty, but importantly guided an efficient search for new elements. A continuous example is a geographic map of the Earth, where any location is unambiguously identified by the latitude and longitude.

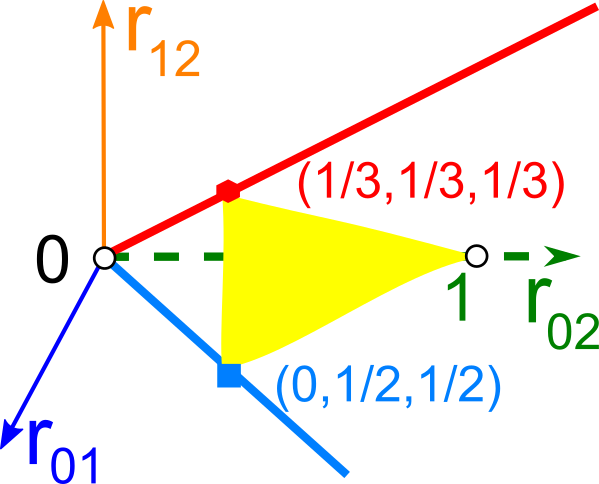

Geometric Data Science aims to develop universal geographic-style coordinates for all real data objects under practically important equivalences, such as rigid motion. The first part of the book focuses on finite point sets. The most important result is a complete and continuous classification of all finite clouds of unordered points under rigid motion in any Euclidean space. The key challenge was to avoid the exponential complexity arising from permutations of the given unordered points. For a fixed dimension of the ambient Euclidean space, the times of all algorithms for the resulting invariants and distance metrics depend polynomially on the number of points.

The second part of the book advances a similar classification in the much more difficult case of periodic point sets, which model all periodic crystals at the atomic scale. The most significant result is the hierarchy of invariants from the ultra-fast to complete ones. The key challenge was to resolve the discontinuity of crystal representations that break down under almost any noise. Experimental validation on all major materials databases confirmed the Crystal Isometry Principle: any real periodic crystal has a unique location in a common moduli space of all periodic structures under rigid motion. The resulting moduli space contains all known and not yet discovered periodic crystals and hence continuously extends Mendeleev’s table to the full crystal universe.

The book was written for research students and professionals who work in mathematics and need rigorously justified and computationally efficient methods for real data. such as crystalline materials and molecules, including proteins. The pre-requisite knowledge is linear algebra, metric geometry, and calculus at the undergraduate level.

We finish by extending Johannes Kepler’s quote from the 17th century to inspire a transformation from brute-force computations, which currently ‘burn’ our planet, to a 21st-century Maths for Science revolution: where there is Data, there is Geometry.

The initial question that can be asked about any real data object is what is it? or (more formally) how is it defined? or (more deeply) how can we make sense of this data?

The first obstacle in achieving these goals is to embrace differences between real objects and their digital representations. For example, a car is a physical object that is very different from a pixel-based image of this car, which is only a matrix of integers.

The second obstacle is the ambiguity of digital representations in the sense that any real object can have many representations that look very different to a computer.

If measurements have continuous real values, the resulting space of representations is infinite. Even if we fix a finite resolution of physical measurements, all potential data values still live in a huge space. For example, all images of size 2 × 2 pixels and greyscale intensities 0, . . . , 255 form a huge collection

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.