Brain-body co-evolution enables animals to develop complex behaviors in their environments. Inspired by this biological synergy, embodied co-design (ECD) has emerged as a transformative paradigm for creating intelligent agents-from virtual creatures to physical robots-by jointly optimizing their morphologies and controllers rather than treating control in isolation. This integrated approach facilitates richer environmental interactions and robust task performance. In this survey, we provide a systematic overview of recent advances in ECD. We first formalize the concept of ECD and position it within related fields. We then introduce a hierarchical taxonomy: a lower layer that breaks down agent design into three fundamental components-controlling brain, body morphology, and task environment-and an upper layer that integrates these components into four major ECD frameworks: bi-level, single-level, generative, and open-ended. This taxonomy allows us to synthesize insights from more than one hundred recent studies. We further review notable benchmarks, datasets, and applications in both simulated and real-world scenarios. Finally, we identify significant challenges and offer insights into promising future research directions. A project associated with this survey has been created at https://github.com/Yuxing-Wang-THU/SurveyBrainBody.

E MBODIED intelligence (EI) seeks to integrate cognitive capabilities into autonomous machines, enabling them to learn from and adapt to complex environments [1]. Situated at the intersection of artificial intelligence and robotics, EI has achieved significant advancements in fusing perception, decision-making, and actuation, empowering various robots to tackle previously intractable challenges, such as dynamic locomotion [2], [3], end-to-end navigation [4], [5], and dexterous manipulation [6], [7], [8], to name just a few.

In traditional EI, an agent’s morphology (body) is typically hand-designed and treated as a fixed component of the environment, while only its controller (brain) is optimized for task execution. However, this separation presents clear limitations. A pre-specified morphology can constrain sensing and actuation, thereby narrowing the space of achievable behaviors. In other words, when morphological design prioritizes mechanical optimality without considering how it will be controlled, the burden of achieving coordinated behavior shifts almost entirely to the controller. This imbalance often creates a bottleneck in task performance and raises a fundamental question: How should we design the optimal form of an embodied agent to effectively perform tasks in its environment?

The concept of morphological computation [9], [10], [11], [12], [13] posits that a well-designed body can simplify computations typically assigned to the brain, thereby facilitating more efficient behaviors. This perspective introduces a brain-body dynamic: changes in morphology necessitate corresponding adaptations in control to exploit newly acquired capabilities, while environmental feedback can, in turn, guide further refinement of morphology. These synergies have motivated various efforts to improve the current agent design procedure. As a result, embodied co-design (ECD), an integrated framework that co-optimizes an agent’s morphology with its control mechanism to enhance task performance, becomes a critical topic in EI.

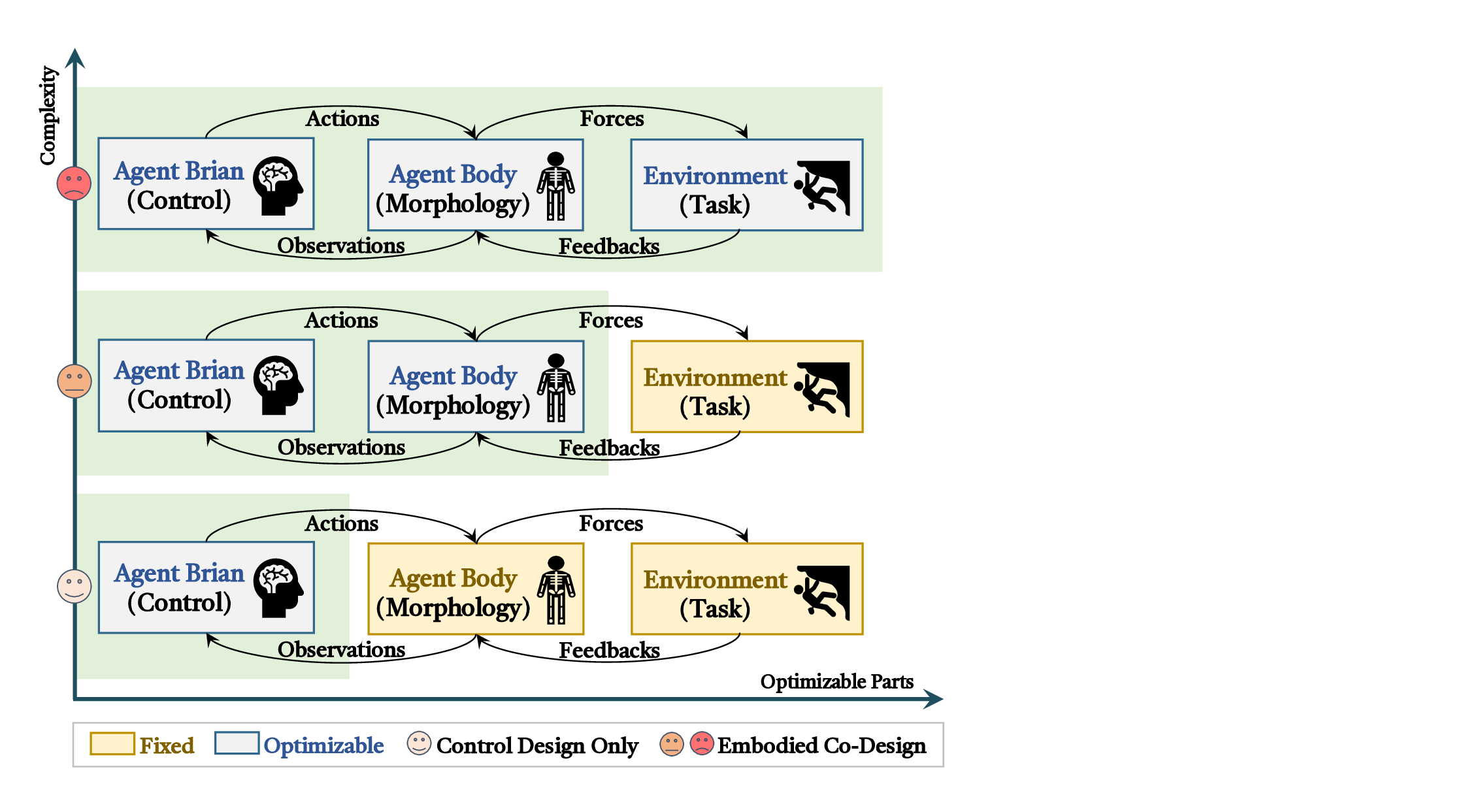

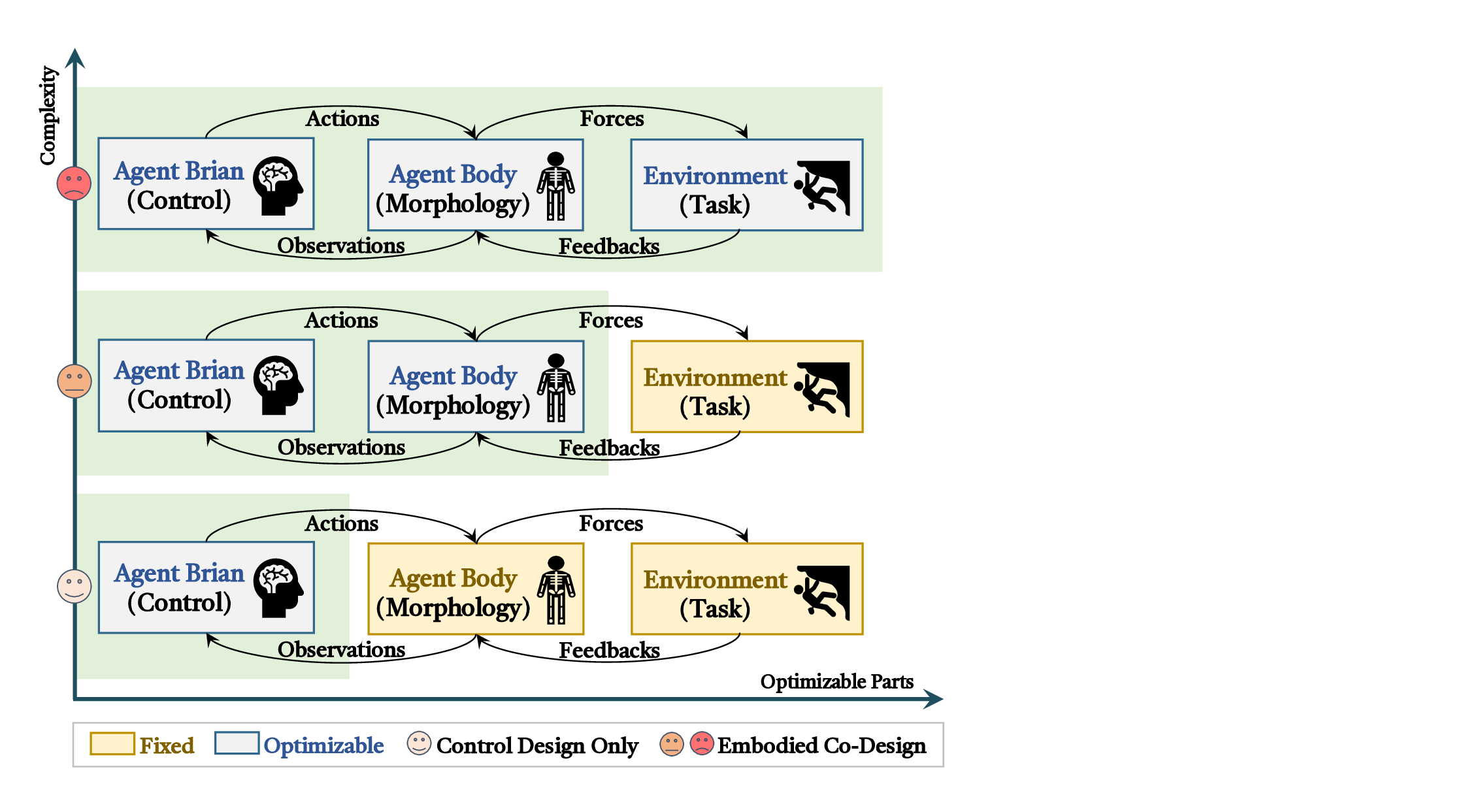

ECD was initially explored in the Evolutionary Robotics (ER) community [14], [15], where both robot morphology and behavior are jointly optimized using Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs) [14]. However, this topic remains emergent for EI, particularly as agents and their tasks continue to increase in complexity and diversity. Compared to controller-only optimization, ECD introduces a vast, often combinatorial design space for morphology-control configurations, accompanied by fragile interdependencies. Specifically, evaluating a candidate morphology typically requires re-training the controller from scratch, as even minor morphological changes can invalidate previously learned controllers. Variations in environmental conditions, design constraints, and task objectives produce heterogeneous feedback signals, further complicating the codesign process (Fig. 1). Consequently, ECD problems are highly non-convex and computationally expensive, underscoring the growing need for automated methodologies instead of traditional manual engineering.

Motivation: Recent breakthroughs in domains such as evolutionary algorithms [16], [17], [18], reinforcement learning (RL) [19], [20], [21], [22], differentiable simulation [23], [24], [25], and large models [26], [27], [28] have led to a surge of novel ECD approaches that rapidly reshape the capabilities of co-design systems. However, their assumptions, representations, computational pipelines, evaluation benchmarks, and limitations have not been systematically reviewed, making it difficult for researchers to develop a coherent understanding of the ECD landscape. Our goal is to clarify the conceptual foundations, consolidate frontier developments, highlight emerging trends, and identify open challenges that will shape the next generation of research in EI.

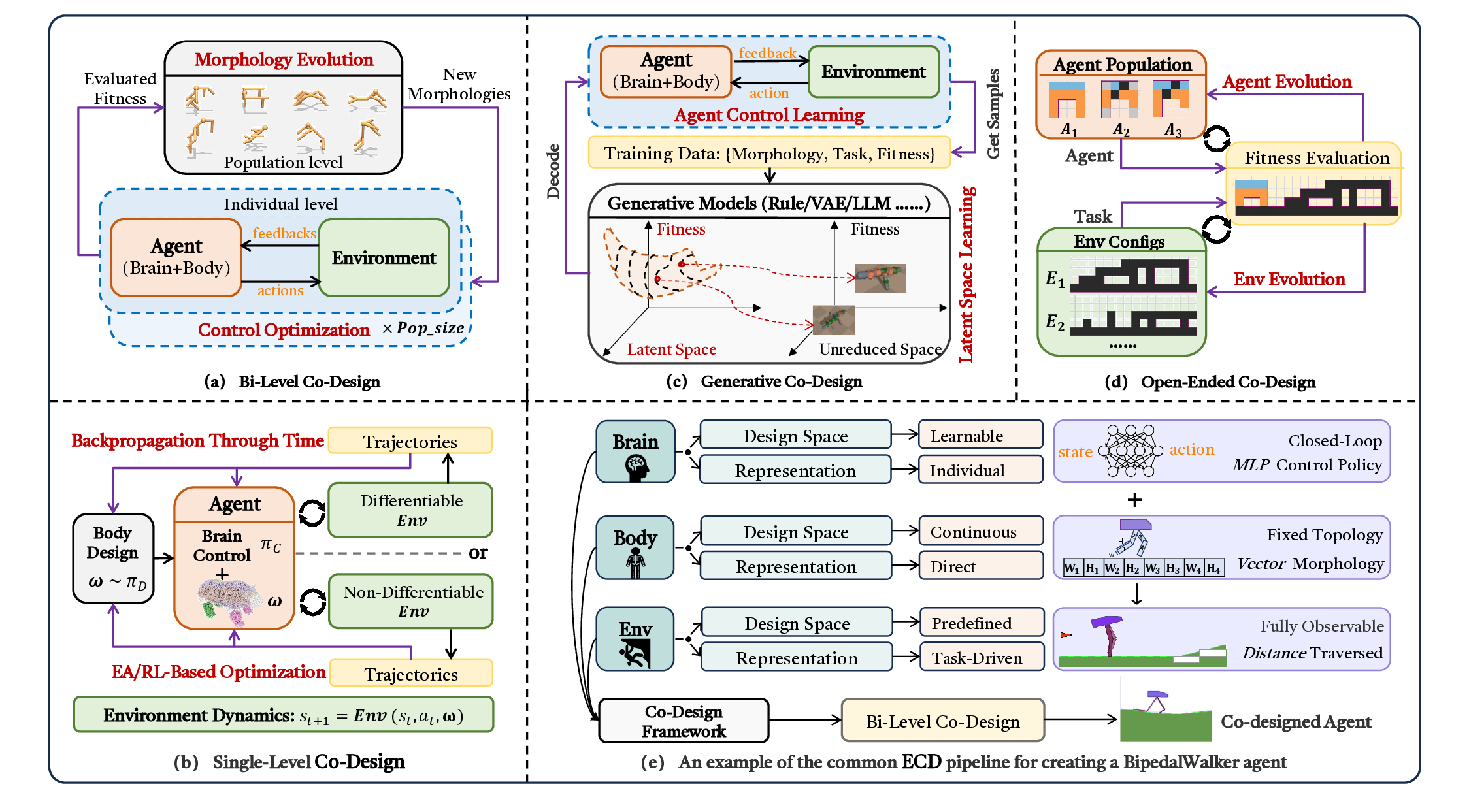

Taxonomy: To enhance readability for researchers across disciplines, we propose a two-layer hierarchical taxonomy in Section III. The lower layer structures ECD around three core dimensions: controlling brain (Section III-A), body morphology (Section III-B), and task environment (Section III-C). Building upon this foundation, the upper layer categorizes existing ECD methods into four major frameworks: bi-level (Section IV-A), single-level (Section IV-B), generative (Section IV-C), and open-ended (Section IV-D), with further subcategories identified within each. This taxonomy establishes a common vocabulary and provides a conceptual map for ECD, facilitating cross-domain understanding. It also encourages researchers to explore beyond their primary areas. For instance, specialists in RL for control optimization may discover how their methodologies align with a specific ECD framework, in conjunction with previously unconsidered morphological evolution, thereby opening pathways for new collaborations.

Scope: Embodied co-design bridges robotics, artificial intelligence, control theory, and cognitive science. Guided by our

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.