Human-annotated datasets with explicit difficulty ratings are essential in intelligent educational systems. Although embedding vector spaces are widely used to represent semantic closeness and are promising for analyzing text difficulty, the abundance of embedding methods creates a challenge in selecting the most suitable method. This study proposes the Educational Cone Model, which is a geometric framework based on the assumption that easier texts are less diverse (focusing on fundamental concepts), whereas harder texts are more diverse. This assumption leads to a cone-shaped distribution in the embedding space regardless of the embedding method used. The model frames the evaluation of embeddings as an optimization problem with the aim of detecting structured difficulty-based patterns. By designing specific loss functions, efficient closed-form solutions are derived that avoid costly computation. Empirical tests on real-world datasets validated the model's effectiveness and speed in identifying the embedding spaces that are best aligned with difficulty-annotated educational texts.

Datasets that are annotated with difficulty levels by educators ("difficulty-annotated educational datasets") are essential for developing educational support systems [1,6]. Although embedding spaces are widely used to represent semantic similarity and are promising for analyzing such datasets, the abundance of embedding methods [8] poses a challenge in selecting suitable methods.

To address this, we propose the Educational Cone Model, which assumes that easier items covering fundamental concepts exhibit lower diversity, while more difficult items are more diverse. This results in a cone-like structure in the embedding space, independent of specific methods. This intuition aligns with the findings of vocabulary acquisition (e.g., Zipf’s law), Piaget’s developmental stages [9], and Bloom’s taxonomy.

We mathematically show that evaluating alignment with this model is reduced to solving an optimization problem that identifies a “difficulty direction” in the embedding space. By designing appropriate loss functions, we derive closed-form solutions, avoiding computationally expensive operations such as centroid comparisons.

Empirical evaluations with recent sentence embeddings confirm that the proposed model enables efficient selection of embedding methods that are well-aligned with difficulty-annotated datasets.

The contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

We propose a geometric model that reflects the assumption that easier items are less diverse in the embedding space.

We show that the model can identify a difficulty direction via optimization.

We formulate this as a closed-form optimization problem.

We demonstrate that this solution requires only mean vector differences between difficulty levels.

We empirically validate the effectiveness of the model on real datasets using recent sentence embeddings.

Let {x 1 , . . . , x N } denote a set of N embedding vectors, where x i is a D-dimensional vector.

We assume that all embedding vectors are normalized; that is, ∥x∥ = 1, where ∥•∥ denotes the Euclidean norm of a vector. The proposed method can be applied to both word and sentence embeddings if these conditions are satisfied. For simplicity, we refer to both words and sentences as items throughout this paper. We introduce a D-dimensional vector w ∈ R D to represent a direction in the embedding space, with the aim of determining the coordinates of w.

We first consider the Educational Cone Model and show that, under simple assumptions, it aligns with the problem of searching for the difficulty direction in the embedding space. The Educational Cone Model assumes that simpler items exhibit lower diversity and more difficult items exhibit higher diversity. We interpret the magnitude of diversity in terms of the spatial spread within the embedding space. Assuming that simpler items exhibit lower diversity, their embedding vectors have a smaller spread in the embedding space. By further refining the notion that simpler items exhibit lower diversity, we assume the existence of the “simplest item.” Embedding vector spaces are typically structured such that semantically similar items are positioned closer together. Hence, in the embedding vector space, the simplest item is assumed to reside in the least-spread-out region, represented by a point e. If we consider difficulty as a component of “semantic similarity,” items closer to e should be simpler, whereas those farther away should be more difficult.

In the Educational Cone Model, suppose that x i is simpler than x j . Based on the above discussion, x i is closer to the simplest item e than x j . Measuring the distance using the Euclidean distance and assuming that all x are normalized to ∥x∥ = 1, we obtain the following transformations:

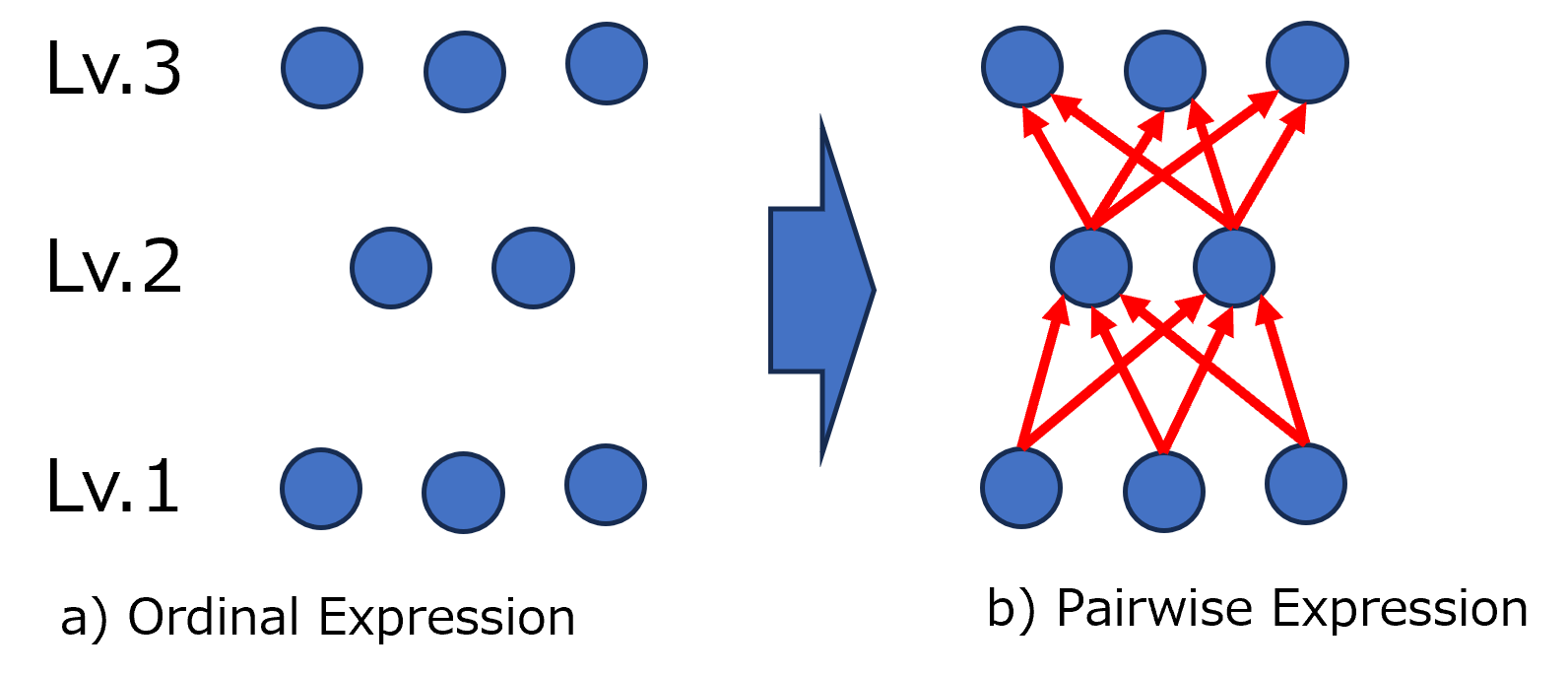

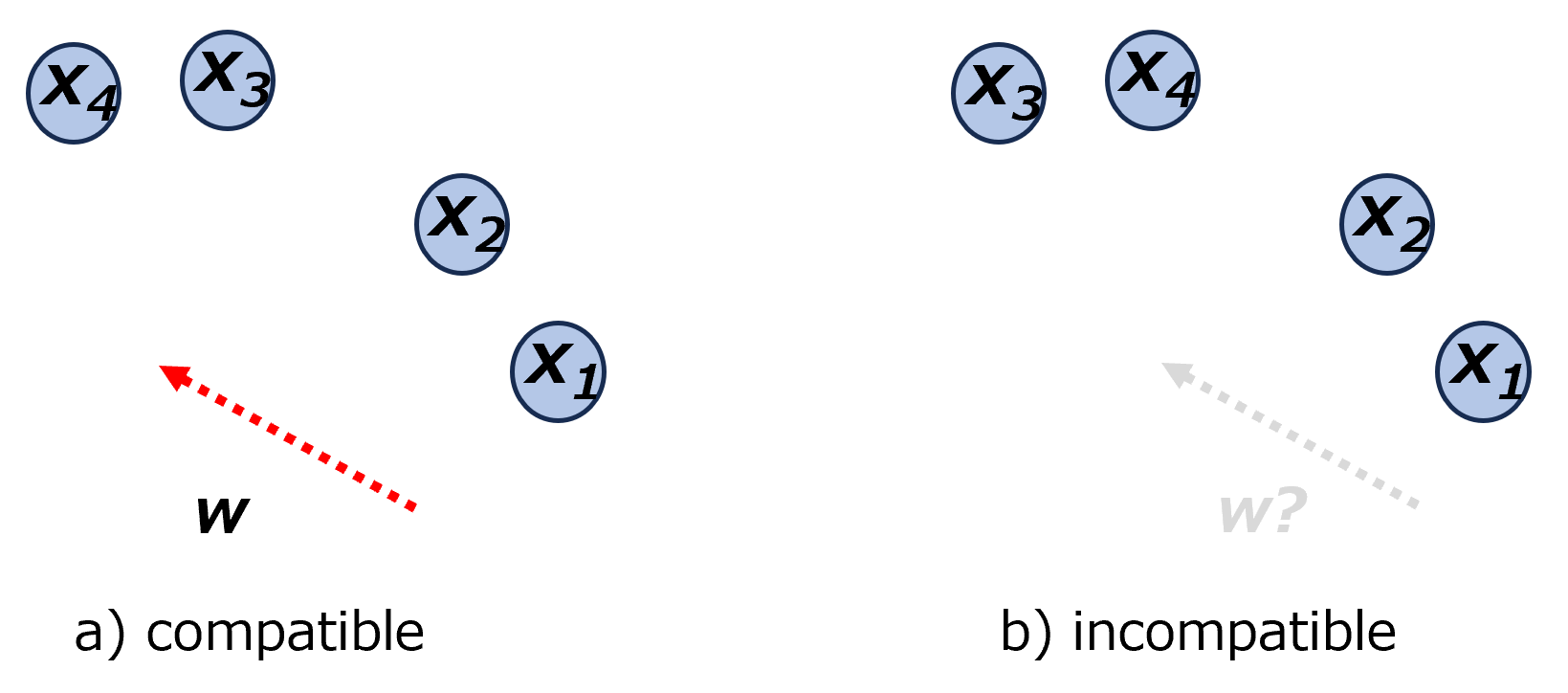

where we define w = -e. The vector w represents a direction in the embedding vector space. The expression w ⊤ x i implies that items can be arranged in order along this direction. Consequently, the direction w indicates that moving in this direction within the embedding vector space corresponds to increasing difficulty. We provide an intuitive interpretation of the difficulty direction w. Simply put, the difficulty direction w represents the direction in which all items in the dataset (annotation set) appear, arranged in order of difficulty. Although determining an ideal direction is preferable, it is often unrealistic. To address this, we allow slight deviations in the order of difficulty. To this end, we first introduce the concept of compatibility (Figure 1, left).

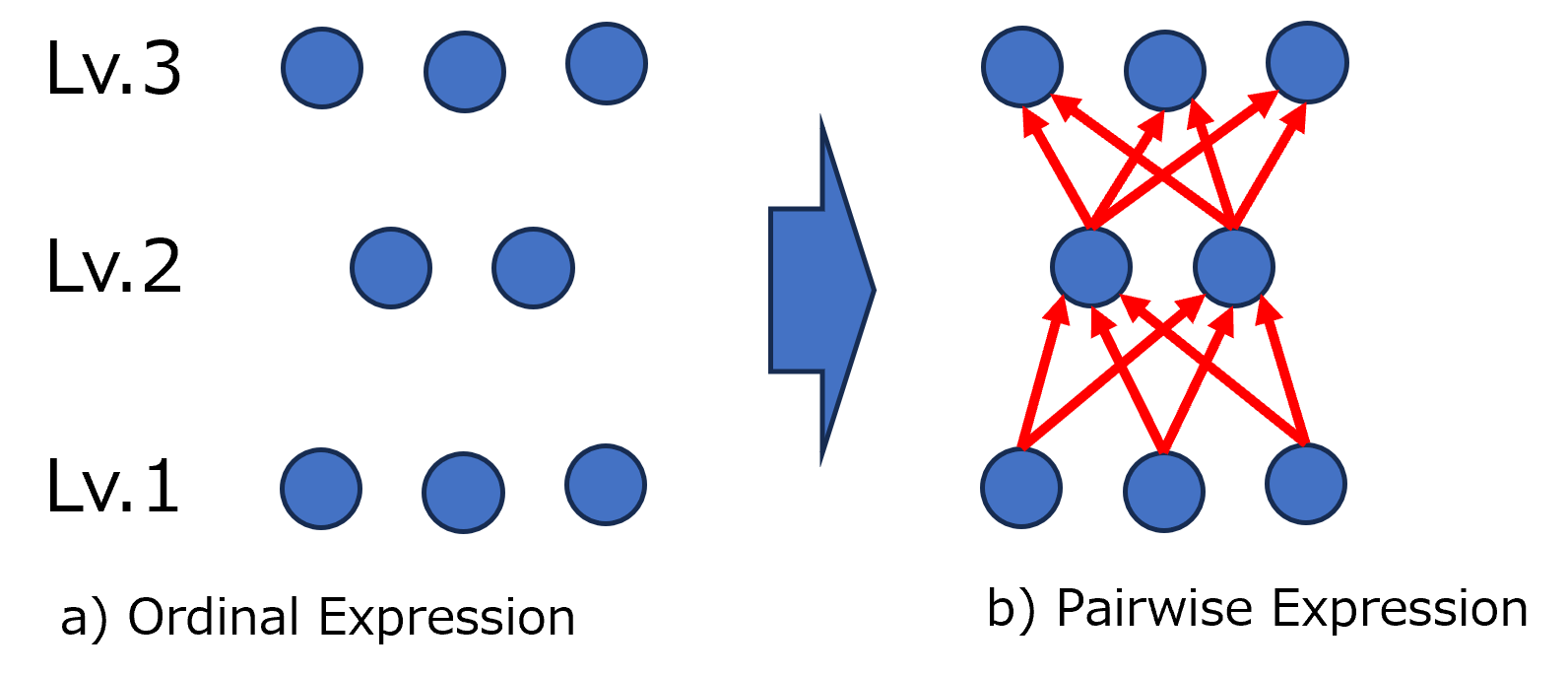

In practice, difficulty annotations are often provided in ordinal levels rather than as direct pairwise relationships. For example, a question might be annotated as high-school or university level rather than being directly compared to another question (Figure 1, right). As shown in panel (a), eight items are annotated using three levels: Levels 1, 2, and 3. These levels, abbreviated as “Lv,” indicate increasing difficulty with high

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.