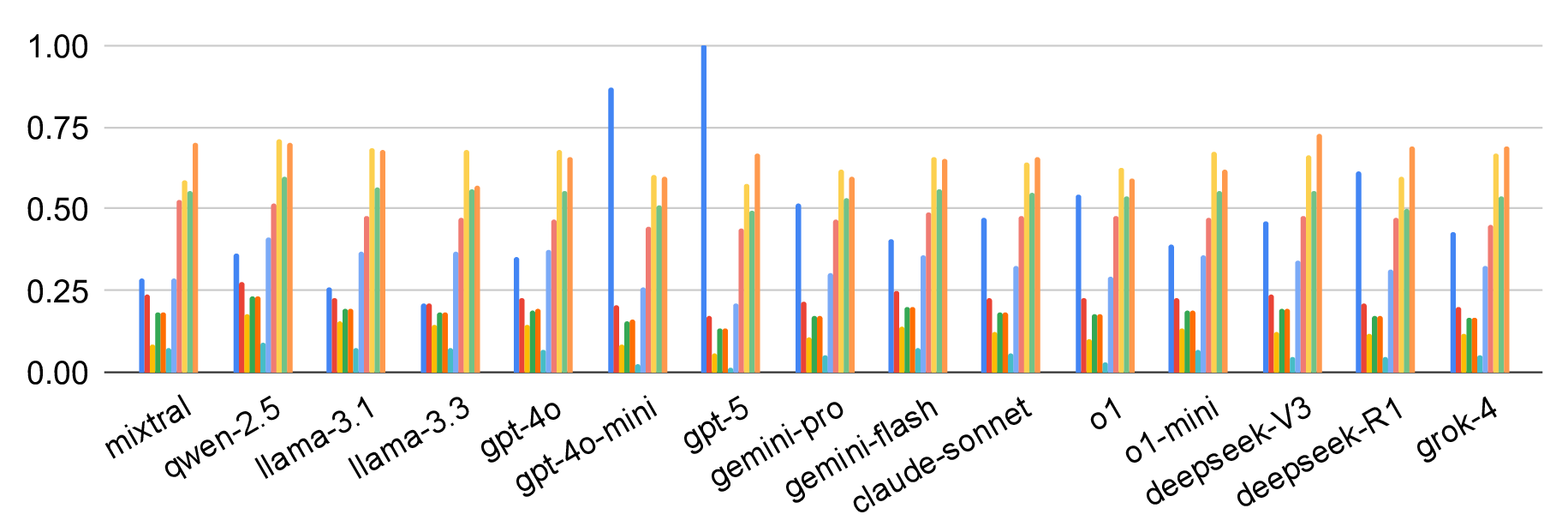

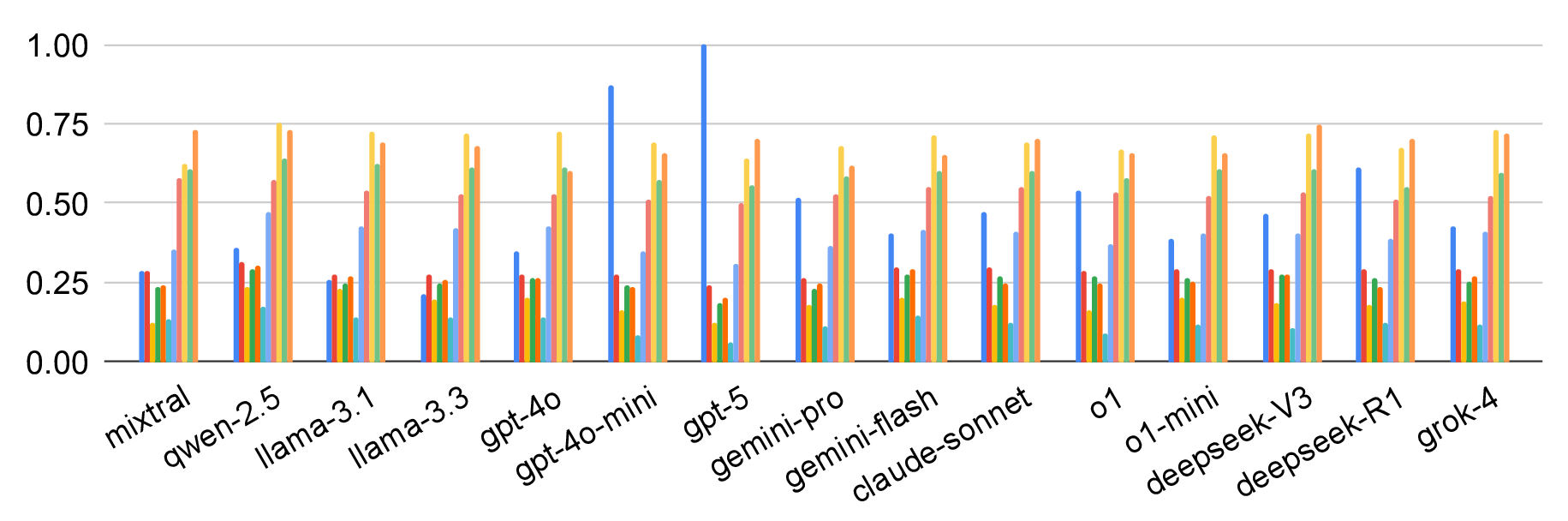

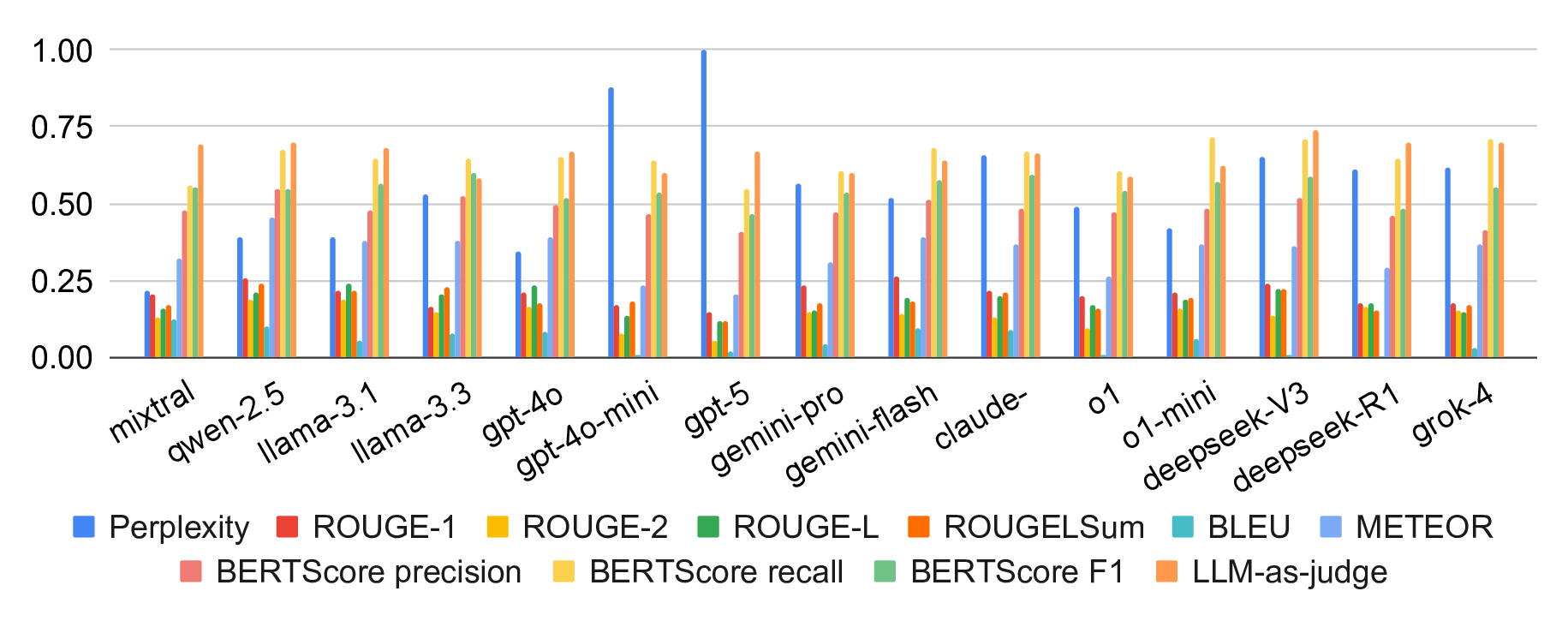

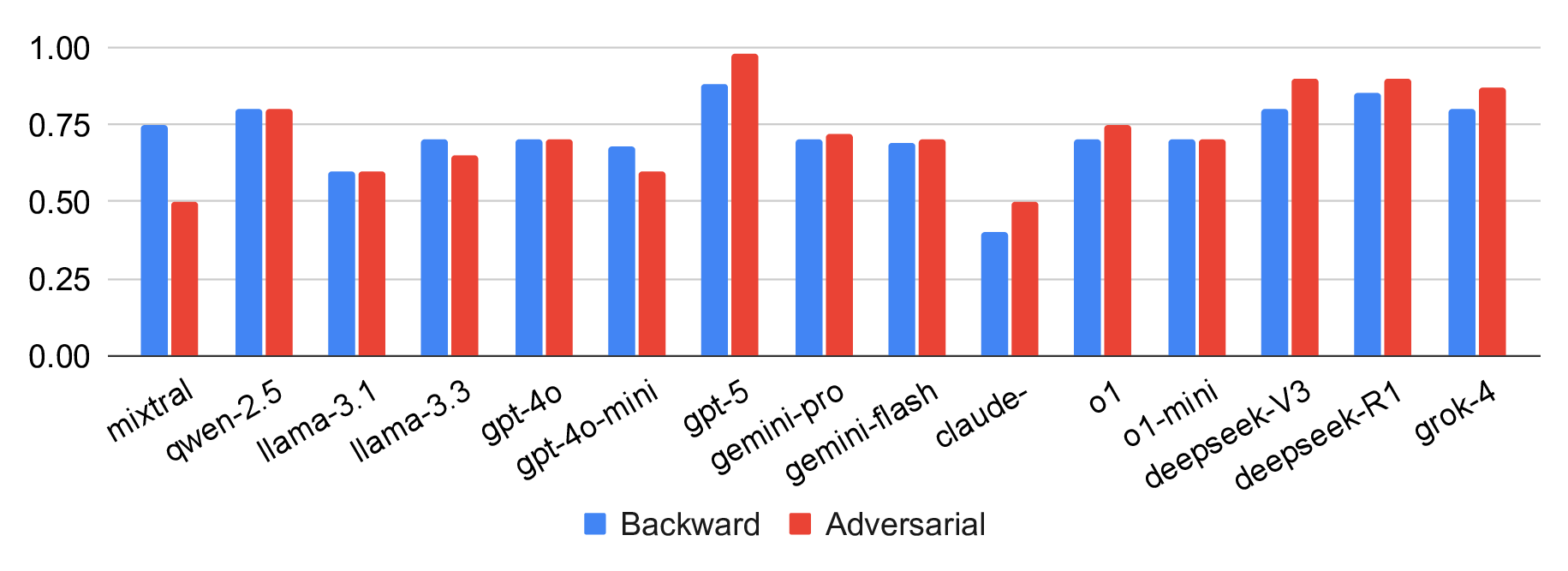

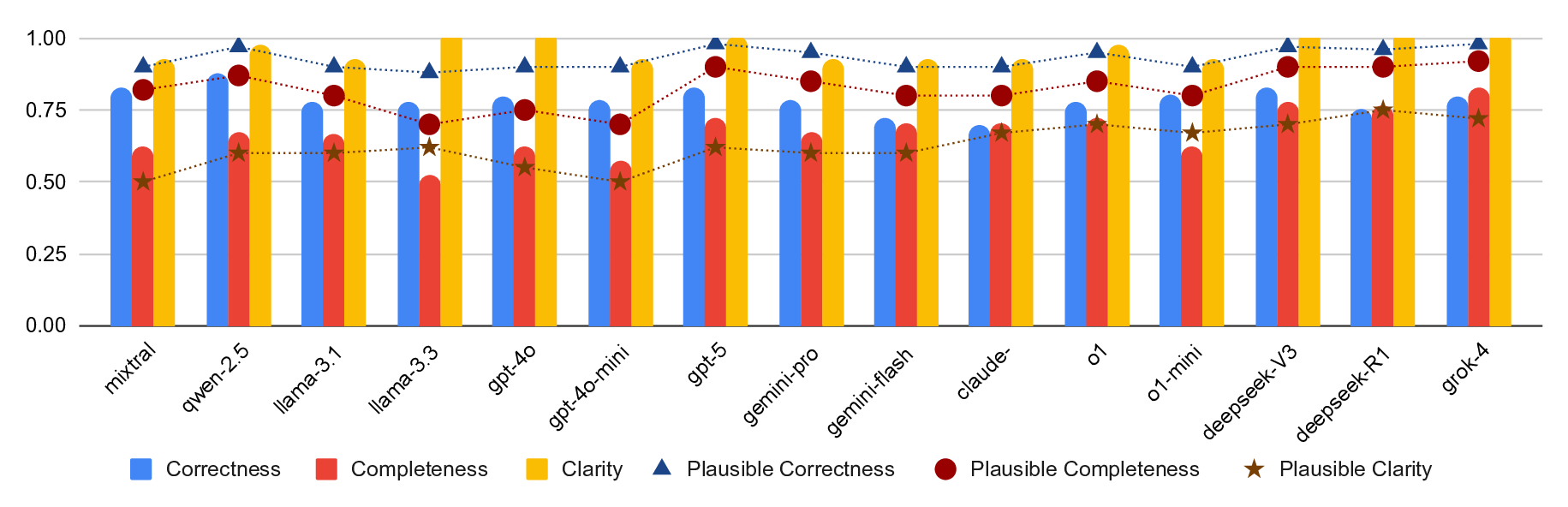

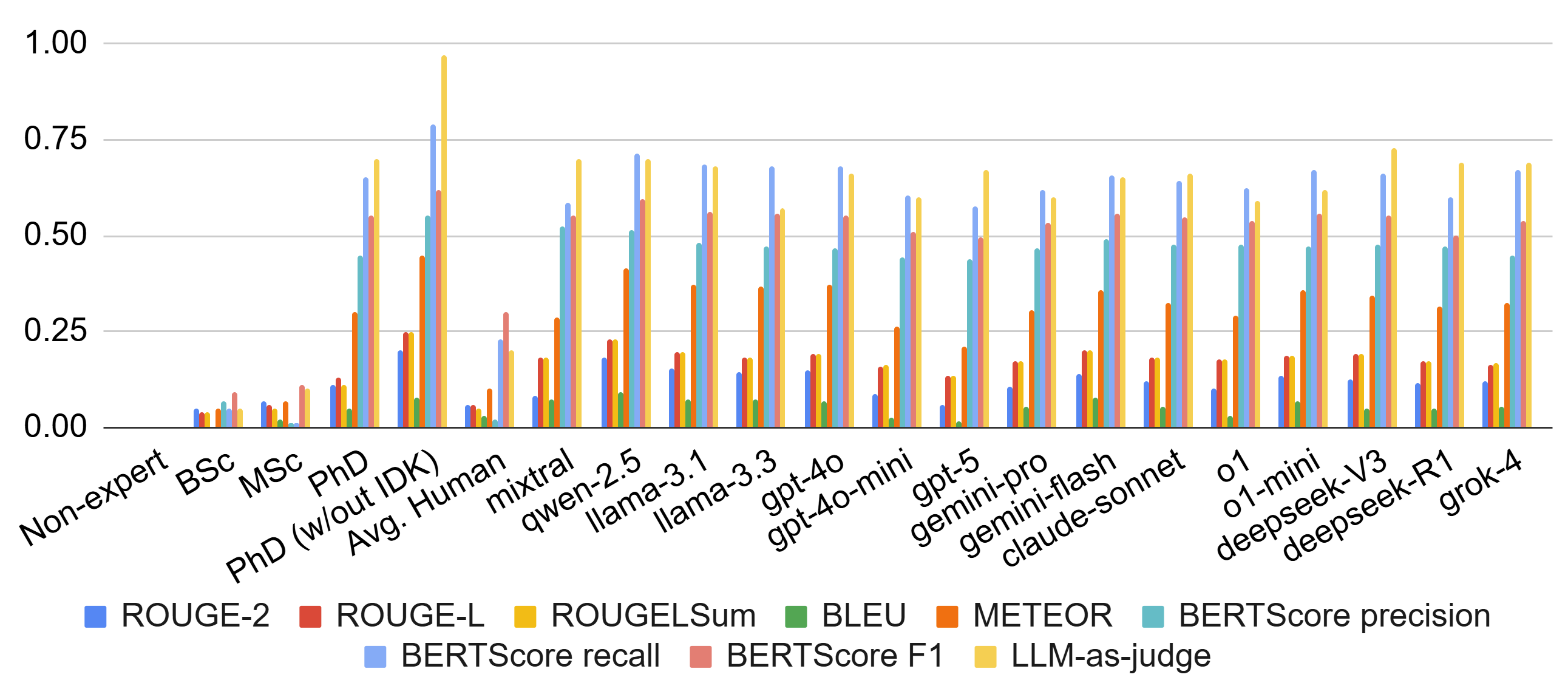

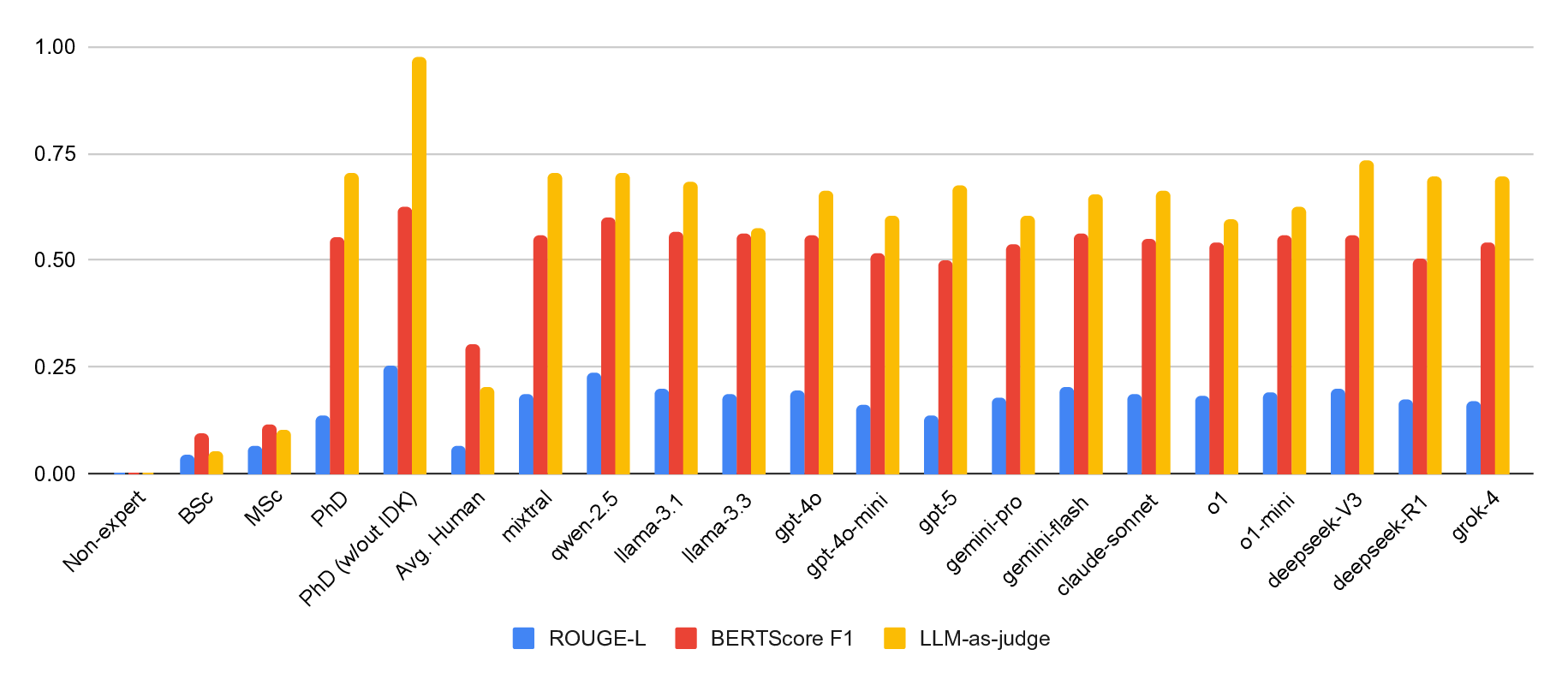

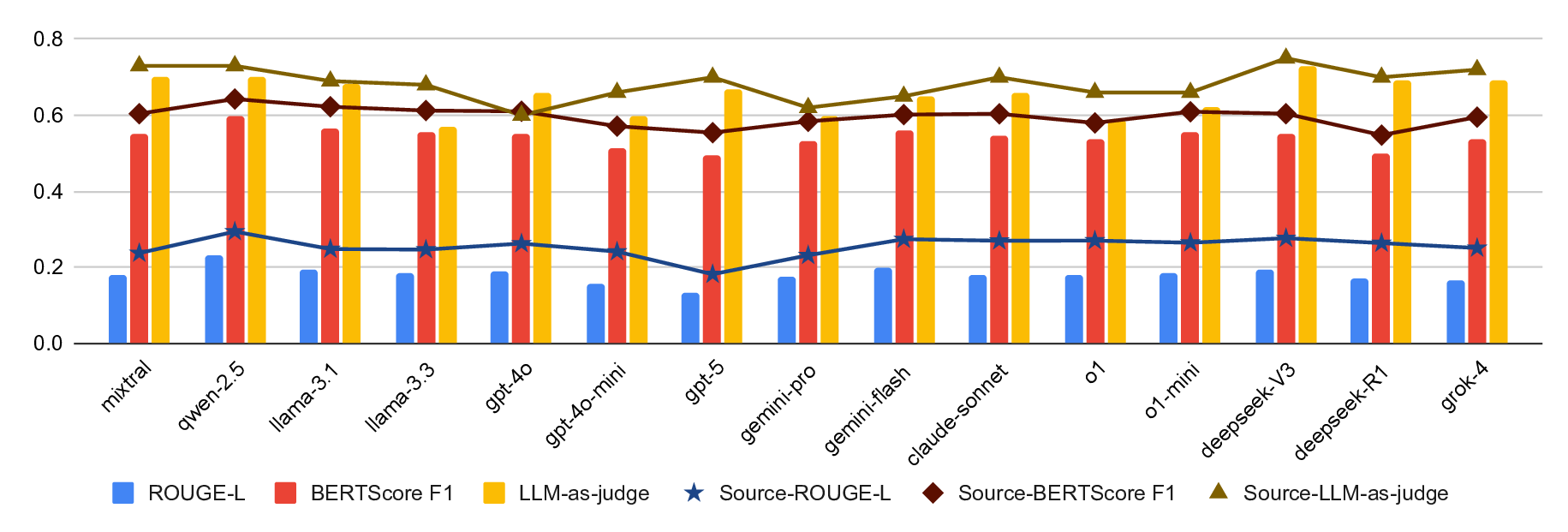

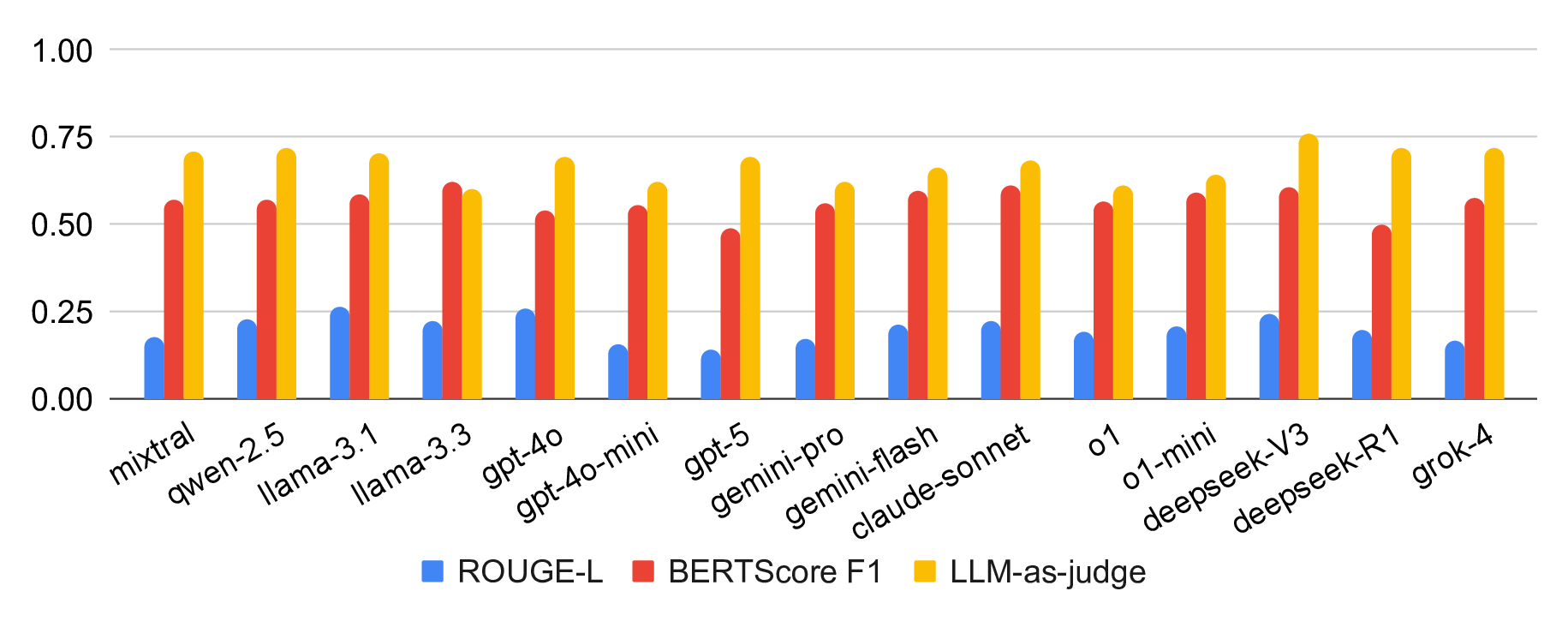

Large language models (LLMs) excel at many general-purpose natural language processing tasks. However, their ability to perform deep reasoning and mathematical analysis, particularly for complex tasks as required in cryptography, remains poorly understood, largely due to the lack of suitable data for evaluation and training. To address this gap, we present CryptoQA, the first large-scale question-answering (QA) dataset specifically designed for cryptography. CryptoQA contains over two million QA pairs drawn from curated academic sources, along with contextual metadata that can be used to test the cryptographic capabilities of LLMs and to train new LLMs on cryptographic tasks. We benchmark 15 state-of-the-art LLMs on CryptoQA, evaluating their factual accuracy, mathematical reasoning, consistency, referencing, backward reasoning, and robustness to adversarial samples. In addition to quantitative metrics, we provide expert reviews that qualitatively assess model outputs and establish a gold-standard baseline. Our results reveal significant performance deficits of LLMs, particularly on tasks that require formal reasoning and precise mathematical knowledge. This shows the urgent need for LLM assistants tailored to cryptography research and development. We demonstrate that, by using CryptoQA, LLMs can be fine-tuned to exhibit better performance on cryptographic tasks.

Artificial intelligent (AI) assistive tools, particularly those based on large language models (LLMs), are fundamentally reshaping how we interact with, design, and apply scientific methods [57,109]. In recent years, LLMs have achieved remarkable progress on a broad spectrum of natural-language-processing (NLP) tasks, including text comprehension, generation, and reasoning [4,32,50,80,85,104]. One of the reasons for this success is the ever-increasing availability of web-crawled language datasets that can be used for training and evaluation. In contrast, training LLMs or assessing their abilities to solve tasks from specialised fields, such as cryptography, remains a challenge [54,63,77,105] because domain-specific datasets are often not available. Nevertheless, in practice, LLMs are used for domain-specific tasks in nearly every field. For example, in our survey, an overwhelming number of cryptographers reported using LLMs daily for their work (cf. Section 5). Our survey aligns well with recent research that discusses the growing adoption of LLMs in cryptography research and practice [5,75]. Naturally, using LLMs for domain-specific tasks without a good understanding of how correct the answers are poses a significant risk. The danger of wrong answers remaining unnoticed is particularly high for LLMs, given their impressive performance on NLP tasks and the resulting trust in LLMs that many of us have developed in recent years [37]. For cryptographic tasks, these errors in model outputs can have substantial consequences, potentially leading to flawed analyses, incorrect proofs, or vulnerabilities in cryptographic protocols [28,39]. Beyond technical risks, such errors carry broader social implications, as cryptography underpins secure communication, financial transactions, and digital privacy. Inaccurate reasoning by LLMs could compromise data security, undermine public trust in digital systems, or facilitate malicious exploitation [25,90]. This highlights the critical need for evaluating LLM capabilities and limitations in cryptography for the following key reasons: Assessing reliability. The reliability of LLM predictions is crucial for both expert and non-expert users in cryptography. Nonexperts-such as software developers or engineers who implement or modify cryptographic protocols-may fail to detect incorrect model outputs, potentially introducing security vulnerabilities. Although experts, such as cryptography researchers, are more likely to identify erroneous predictions by consulting the relevant literature, inaccurate responses may still mislead them initially, reducing research efficiency and slowing the broader adoption of LLMs in cryptographic practice. Guiding model design. Identifying the failure modes of current models allows the development of specialised architectures, pre-training strategies, and domain-specific corpora that improve the performance of LLMs on cryptographic tasks. Benchmarking progress. Standardised evaluations on recognised benchmarks are required for cryptographers to track improvements over time and to make informed decisions regarding the suitability of models for different use cases.

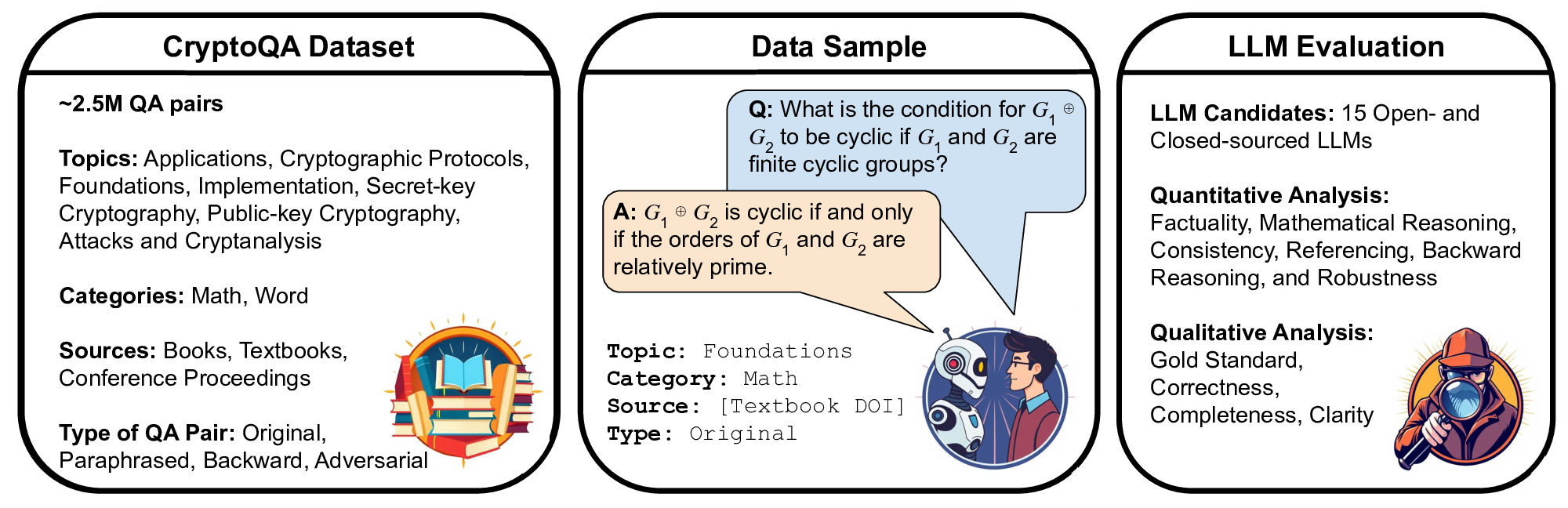

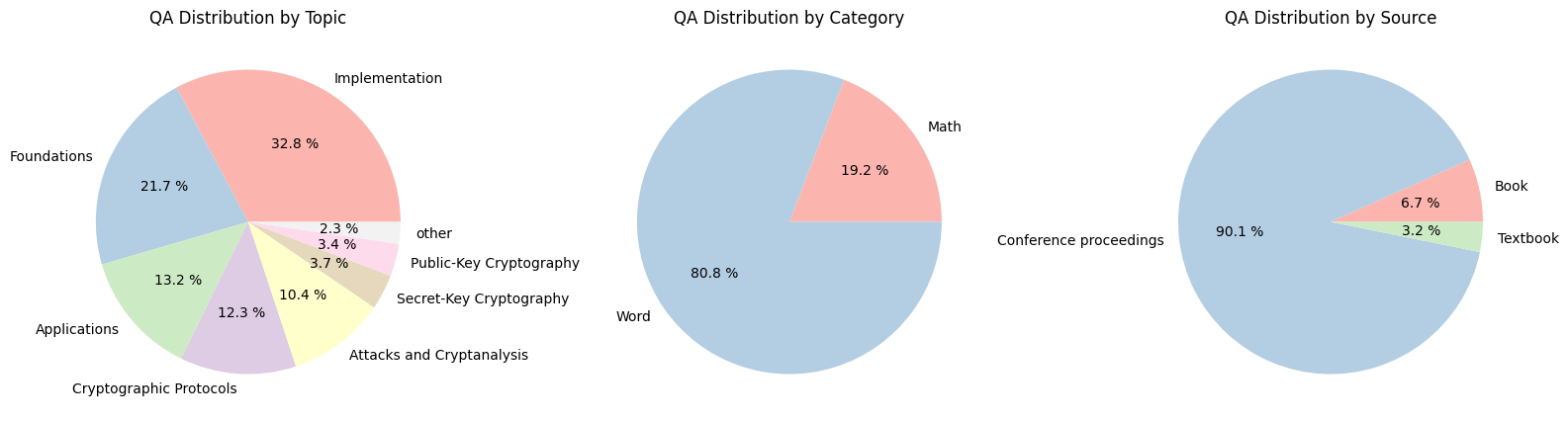

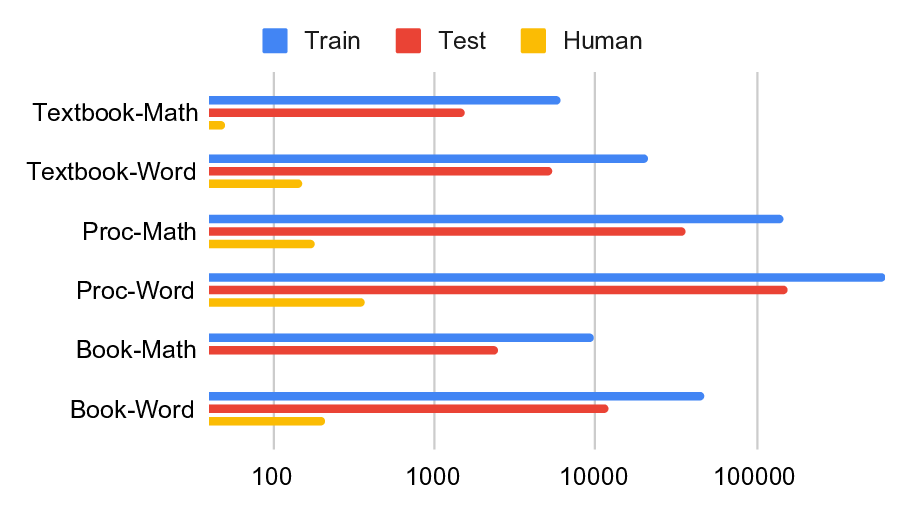

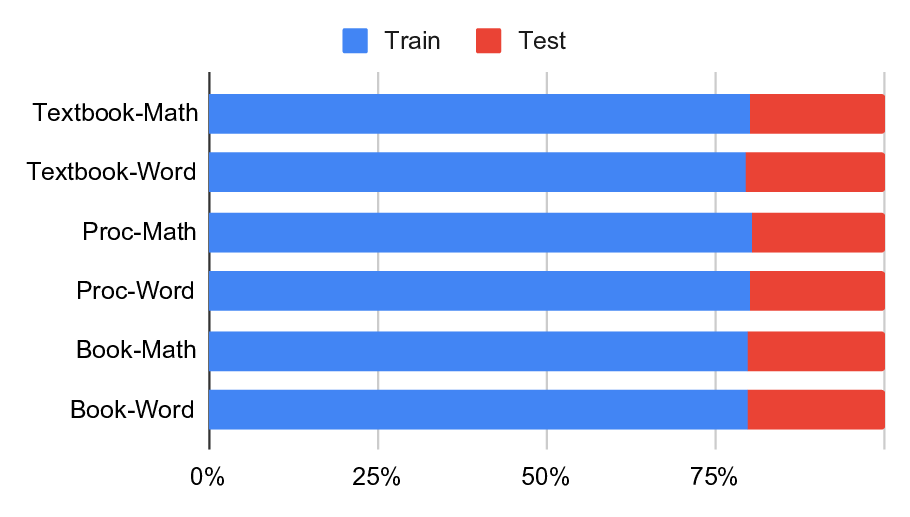

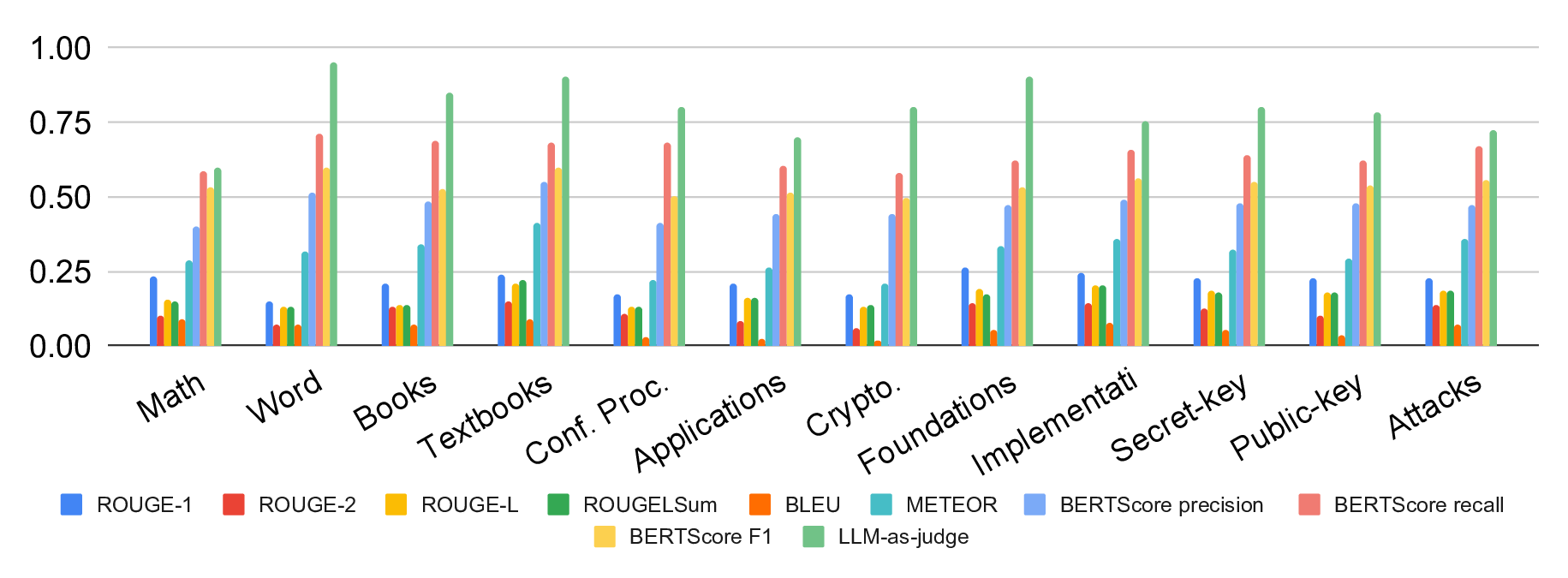

A foundational step towards LLM-assistance in cryptography is creating large-scale, domain-specific datasets that capture the nuanced knowledge and reasoning patterns essential for cryptographic tasks, and that can then be used for the evaluation and training of AI models. We therefore introduce CryptoQA 1 , the first Figure 1: Our new dataset CryptoQA is the first large-scale cryptography dataset with over 2.5M QA pairs with rich metadata, i.e., different topics, categories, sources, and types of QA pairs (cf. Section 3). We use CryptoQA to quantitatively and qualitatively evaluate existing state-of-the-art LLMs for their cryptographic capabilities, such as factuality and mathematical reasoning, w.r.t. different metrics (cf. Sections 4 and 5). (Icons generated by deepai.org.) large-scale cryptography dataset comprising more than two million question-answer (QA) pairs that span all major sub-fields of cryptography (see Fig. 1). While existing datasets rely primarily on deterministic or expert-validated approaches to ensure reliability, they are often limited in scale and domain coverage. In contrast, we ensure high-quality data by only drawing content from peerreviewed articles, such as journal articles, textbooks, or conference proceedings. To cover a wide variety of journals and conferences, and to consistently add metadata to the articles, we started with articles from the International Association for Cryptologic Research’s (IACR) ePrint Archive [48]. The eprints were then matched with peer-reviewed articles, and the peer-reviewed version was used for our dataset, along with the corresponding metadata from [48], e.g., topics and sources(cf. Section 3 for more details). This allowed for a scalable and consistent annotation without incurring the cost of manual labelling (cf. Section 3 for

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.