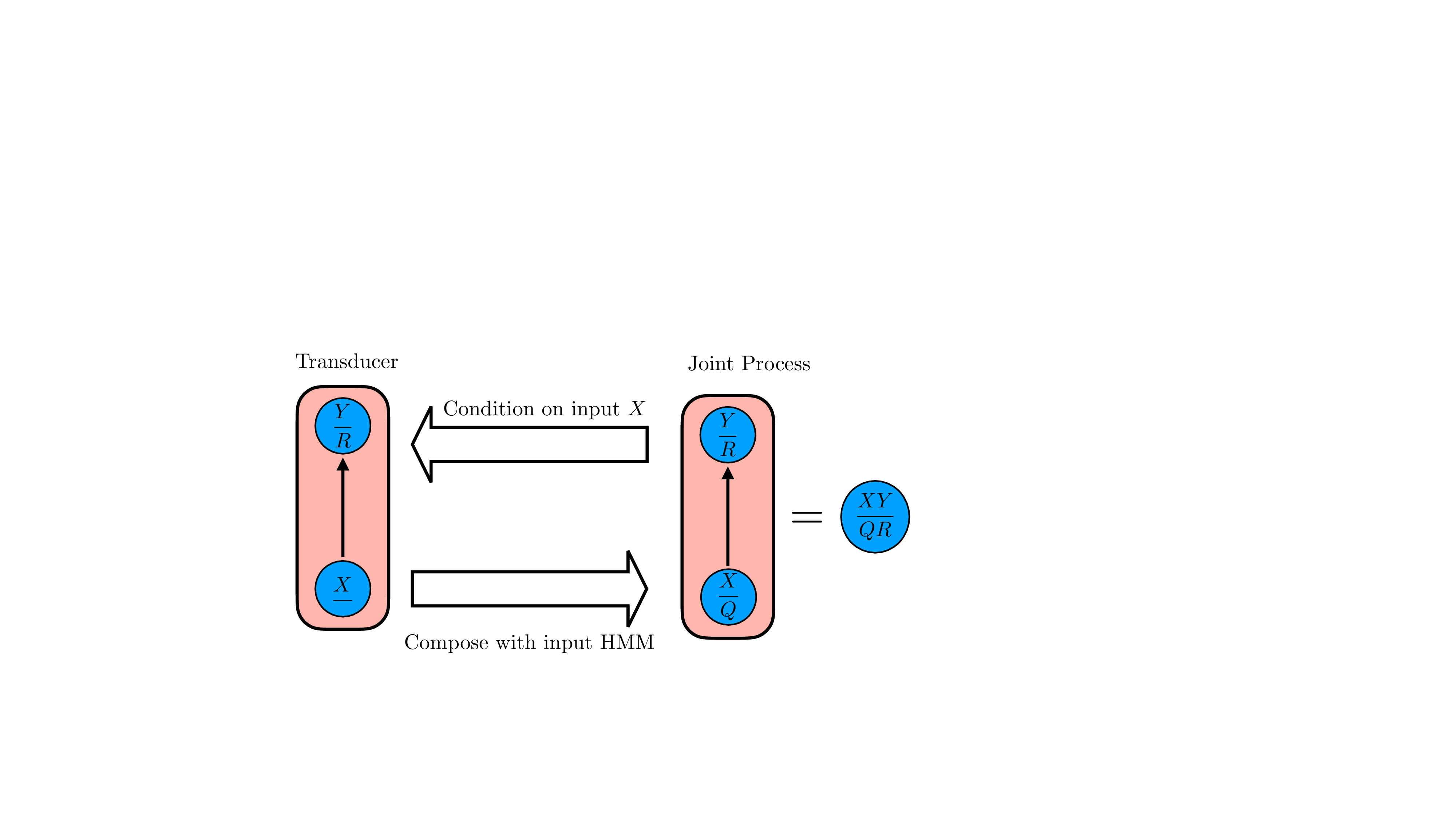

World models have been recently proposed as sandbox environments in which AI agents can be trained and evaluated before deployment. Although realistic world models often have high computational demands, efficient modelling is usually possible by exploiting the fact that real-world scenarios tend to involve subcomponents that interact in a modular manner. In this paper, we explore this idea by developing a framework for decomposing complex world models represented by transducers, a class of models generalising POMDPs. Whereas the composition of transducers is well understood, our results clarify how to invert this process, deriving sub-transducers operating on distinct input-output subspaces, enabling parallelizable and interpretable alternatives to monolithic world modelling that can support distributed inference. Overall, these results lay a groundwork for bridging the structural transparency demanded by AI safety and the computational efficiency required for real-world inference.

Advances in deep reinforcement learning have produced agents that can operate in increasingly complex environments, from dexterous robotic control and large-scale games to open-ended dialogue and tool use (Andrychowicz et al., 2020;Berner et al., 2019;Ouyang et al., 2022;Rajeswaran et al., 2017). As these systems become more powerful and autonomous and are considered for deployment in high-stakes settings, questions about reliability, safety, and interpretability are beginning to take central stage (Bengio et al., 2024;Glanois et al., 2024;Tang et al., 2024). One way to address these questions is by adopting world models as controlled testbeds, serving as synthetic environments in which agents can be trained, probed, and stress-tested before deployment (Dalrymple et al., 2024;Bruce et al., 2024;Díaz-Rodríguez et al., 2023). However, the usefulness of such sandboxing depends critically on our ability to build world models that are faithful enough to guarantee that the agent's behaviour in simulation can be transferred to real-world settings (Rosas et al., 2025;Ding et al., 2025).

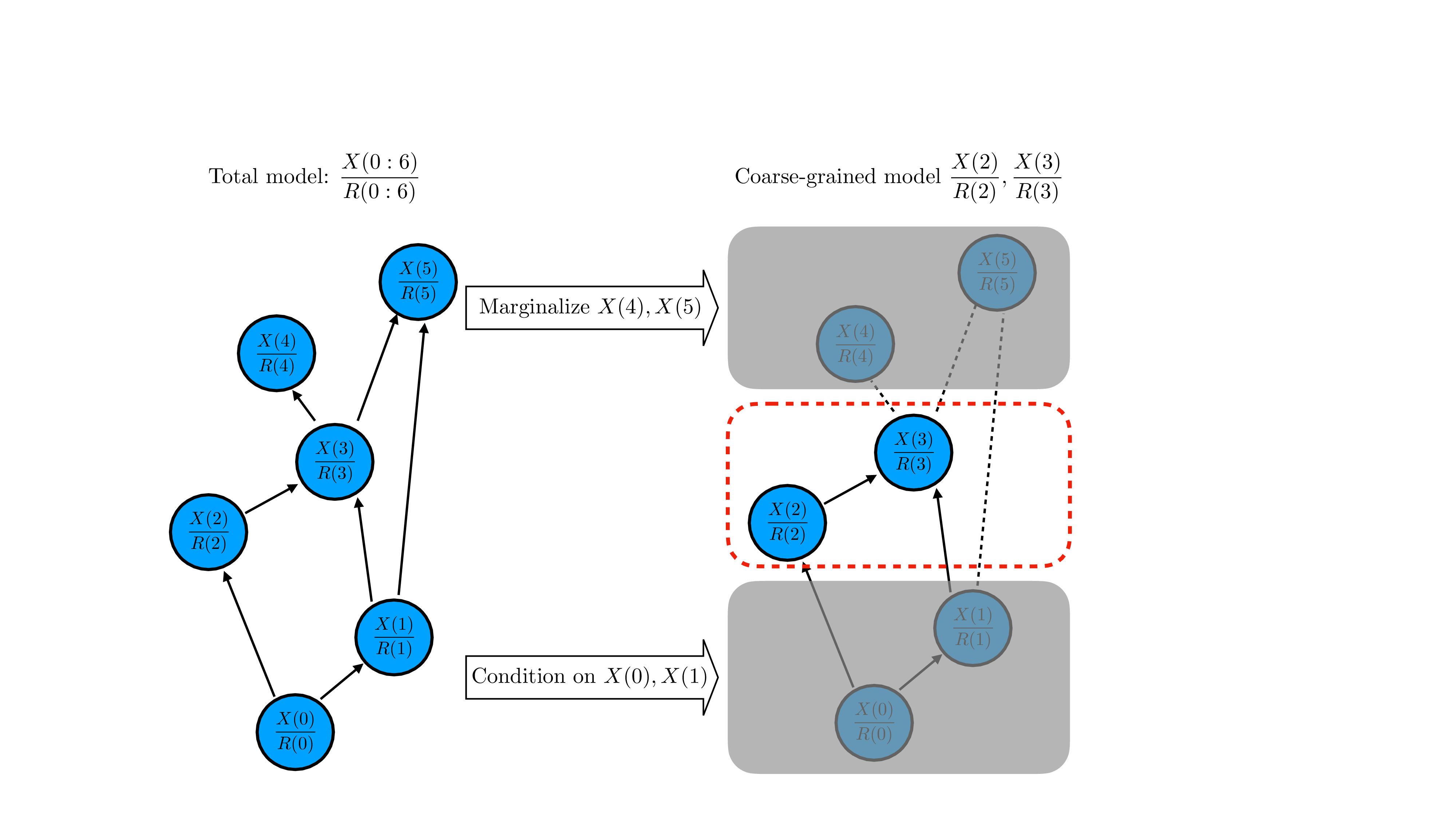

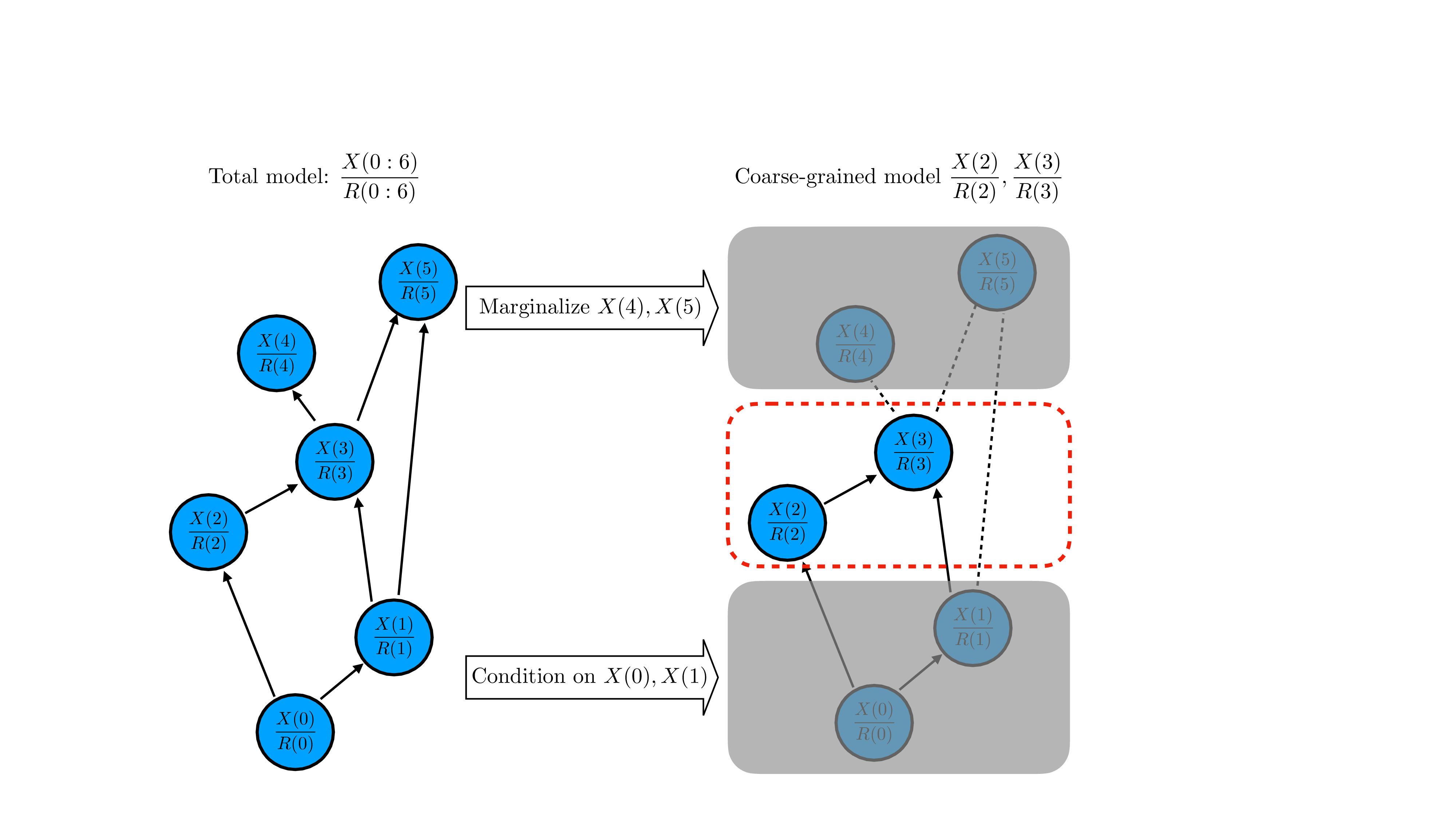

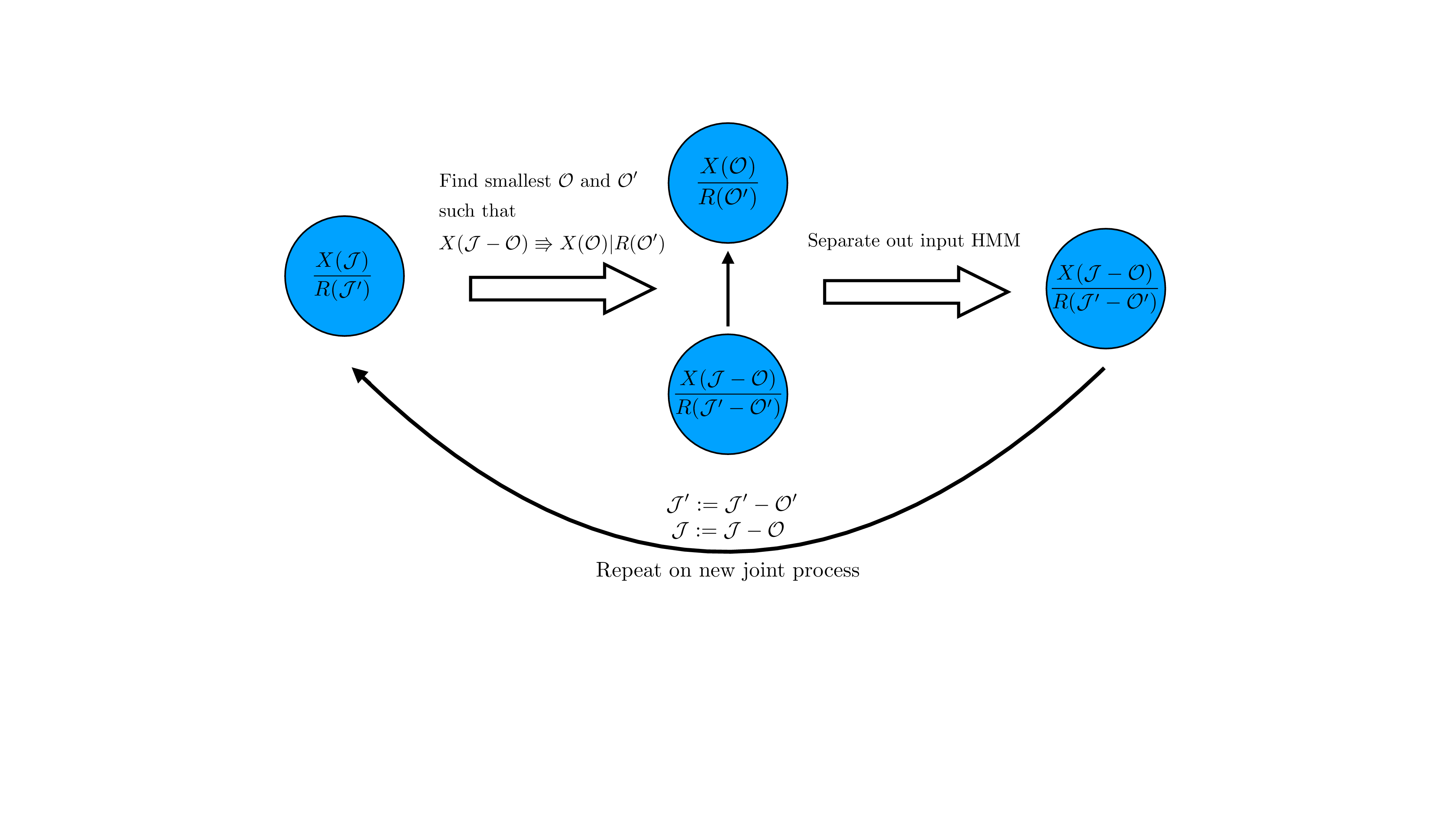

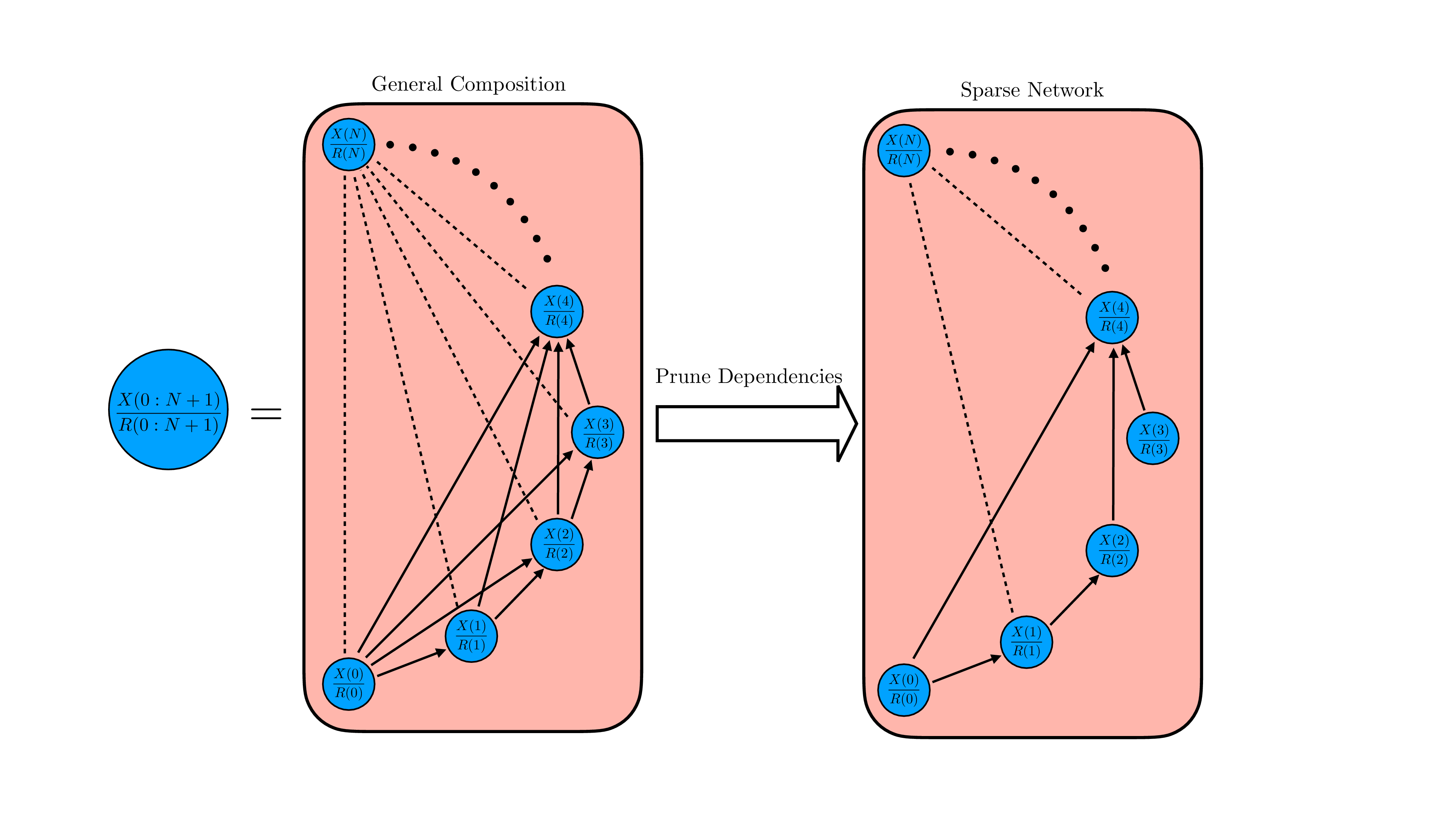

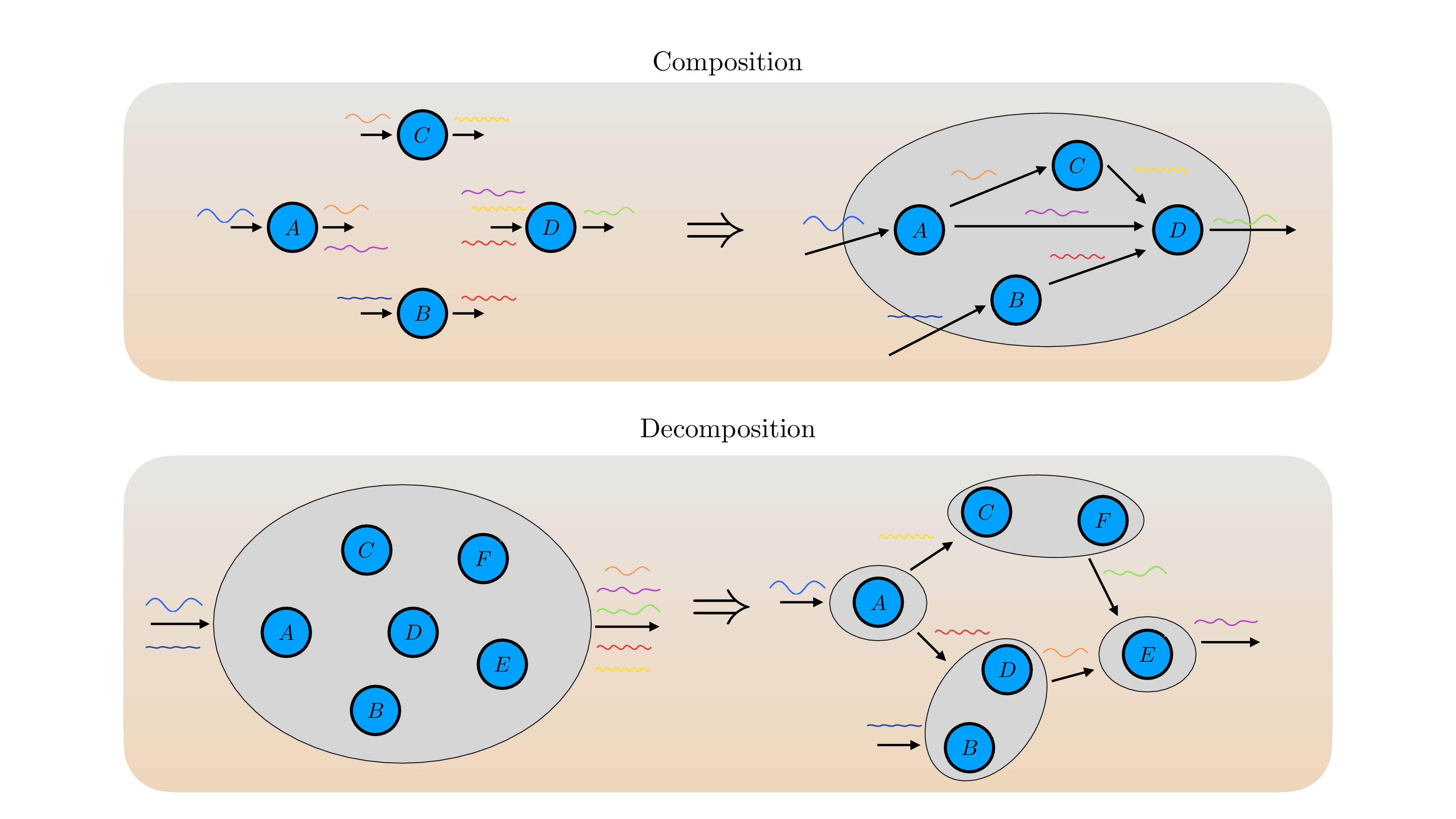

An environment can be formally described as a transducer that turns input sequences (e.g., actions) into output sequences (e.g., observations and rewards) (Ding et al., 2025). This transduction, however, happens via interwoven dynamics often involving co-occurring physical processes alongside social interactions, biological rhythms, or engineered feedback loops. A surfer, for instance, must simultaneously navigate the ocean’s turbulence and the coordinated movements of their companions; naively modelling all of this as a single high-dimensional mechanism makes learning and inference expensive and blurs the underlying structure. For world models to be useful as scientific tools, they should instead expose modularity: distinct components should track different aspects of the world, while still interacting and combining to produce coherent global behaviour. Prior work related to the modularity of transduction has mostly approached this from a bottom-up perspective, focusing on how small components can be composed into layered networks that capture complex input-output relationships (Hopcroft & Ullman, 1979;Mohri, 1997;Mohri et al., 2002).

From the perspective of model-based reinforcement learning, one is typically concerned with learning a model of the underlying transition dynamics of the environment, which can be used for several downstream tasks such as planning and training policies (Hafner et al., 2020;2025;Hansen et al., 2024). However, simulating and learning the transition dynamics of high-dimensional data (such as video data) in “entangled” latent spaces is complex, computationally expensive, and less interpretable. Leveraging the fact that ordinary human-scale environments often consist of sparse interactions between multiple distinct entities, several works have demonstrated the benefits of incorporating inductive biases to force neural networks to represent the world as a set of discrete objects, such as generalisation (Goyal et al., 2021;Zhao et al., 2022;Feng & Magliacane, 2023), sample efficiency (Rodriguez-Sanchez et al., 2025), interpretability (Mosbach et al., 2025), compositional generation (Baek et al., 2025), and robustness to noise (Liu et al., 2023).

While composition explains how modular systems can be built, for AI safety and interpretability, we often face the inverse problem: given a large, seemingly entangled world model, how can we decompose it into simpler, interpretable pieces without sacrificing predictive power? x u b W / n t w s 7 u 3 v 5 B 8 f C o q e N U M W y w W M S q H V C N g k t s G G 4 E t h O F N A o E t o L R 3 c x v P a H S P J Y P Z p y g H 9 G B 5 C F n 1 F i p f t M r l t y y O w d Z J V 5 G S p C h 1 i t + d f s x S y O U h g m q d c d z E + N P q D K c C Z w W u q n G h L I R H W D H U k k j 1 P 5 k f u i U n F m l T 8 J Y 2 Z K G z N X f E x M a a T 2 O A t s Z U T P U y 9 5 M / M / r p C a 8 9 i d c J q l B y R a L w l Q Q E 5 P Z 1 6 T P F T I j x p Z Q p r i 9 l b A h V Z Q Z m 0 3 B h u A t v 7 x K m p W y d 1 G u 1 C 9 L 1 d s s j j y c w C m c g w d X U I V 7 q E E D G C A 8 w y u 8 O Y / O i / P u f C x a c 0 4 2 c w x / 4 H z + A J Q r j M k = < / l a t e x i t > B < l a t e x i t s h a 1 _ b a s e 6 4 = " w W 6 O X Y F o J g 3 R v l r Y I d l x q P z Q z S E = " > A A A B 6 H i c b V D L T g J B E O z F F + I L 9 e h l I j H x R H b R R I 8 E L x 4 h k U c C G z I 7 9 M L I 7 O x m Z t a E E L 7 A i w e N 8 e o n e f N v H G A P C l b S S a W q O 9 1 d Q S K 4 N q 7 7 7 e Q 2 N r e 2 d / K 7 h b 3 9 g 8 O j 4 v F J S 8 e p Y t h k s Y h V J 6 A a B Z f Y N N w I 7 C Q K a R Q I b A f j u 7 n f f k K l e S w f z C R B P 6 J D y U P O q L F S o 9 Y v l t y y u w B Z J 1 5 G S p C h 3 i 9 + 9 Q Y x S y O U h g m q d d d z E + N P q T K c C Z w V e q n G h L I x H W L X U k k j 1 P 5 0 c e i M X F h l Q M J Y 2 Z K G L N T f E 1 M a a T 2 J A t s Z U T P S q 9 5 c / M / r p i a

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.