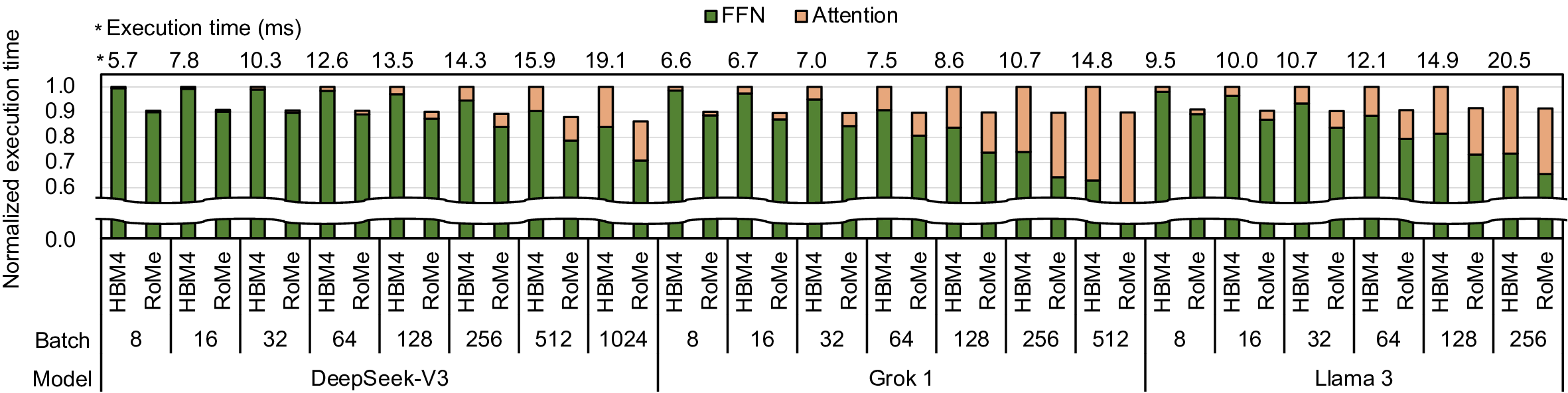

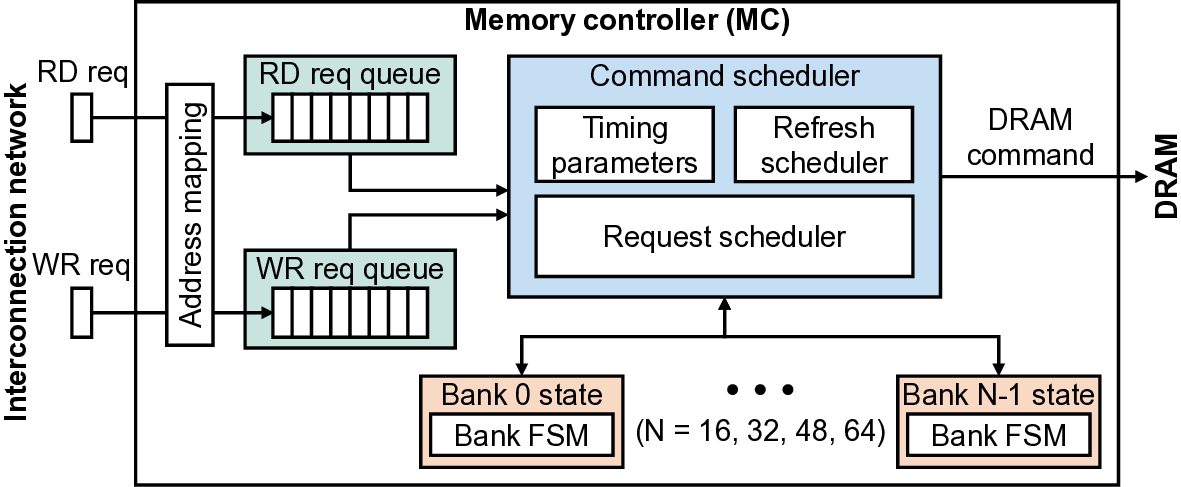

Modern HBM-based memory systems have evolved over generations while retaining cache line granularity accesses. Preserving this fine granularity necessitated the introduction of bank groups and pseudo channels. These structures expand timing parameters and control overhead, significantly increasing memory controller scheduling complexity. Large language models (LLMs) now dominate deep learning workloads, streaming contiguous data blocks ranging from several kilobytes to megabytes per operation. In a conventional HBM-based memory system, these transfers are fragmented into hundreds of 32B cache line transactions. This forces the memory controller to employ unnecessarily intricate scheduling, leading to growing inefficiency.

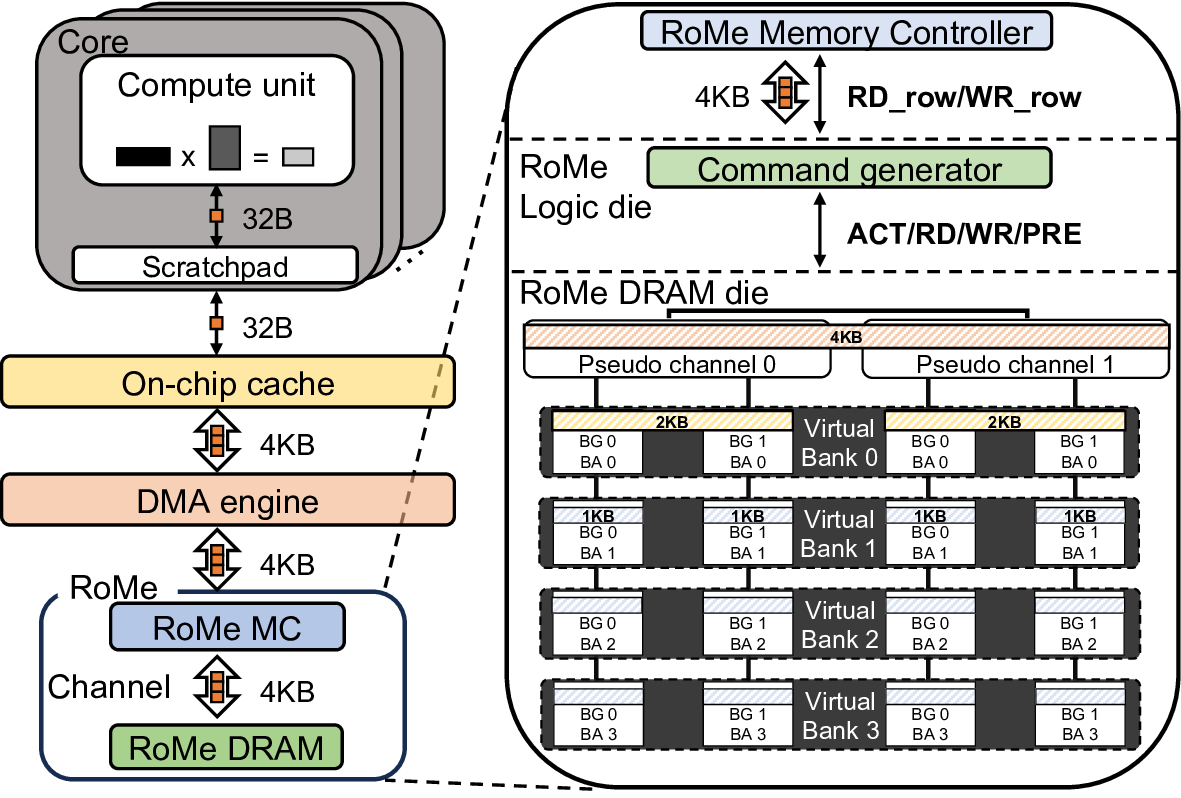

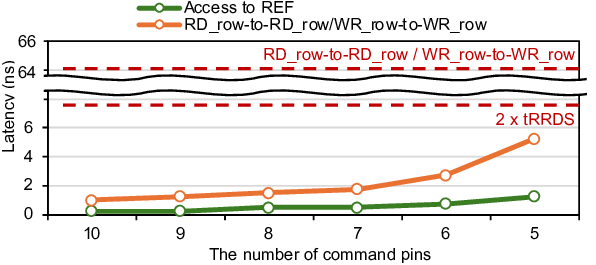

To address this problem, we propose RoMe. RoMe accesses DRAM at row granularity and removes columns, bank groups, and pseudo channels from the memory interface. This design simplifies memory scheduling, thereby requiring fewer pins per channel. The freed pins are aggregated to form additional channels, increasing overall bandwidth by 12.5% with minimal extra pins. RoMe demonstrates how memory scheduling logic can be significantly simplified for representative LLM workloads, and presents an alternative approach for next-generation HBM-based memory systems achieving increased bandwidth with minimal hardware overhead.

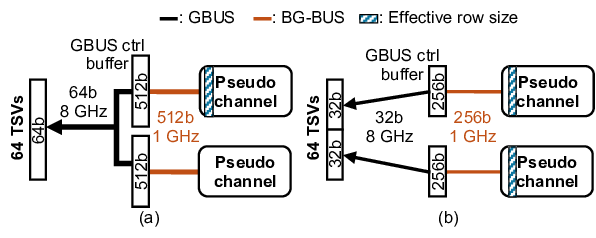

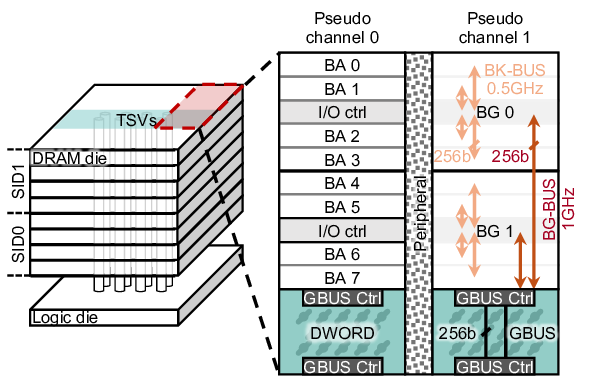

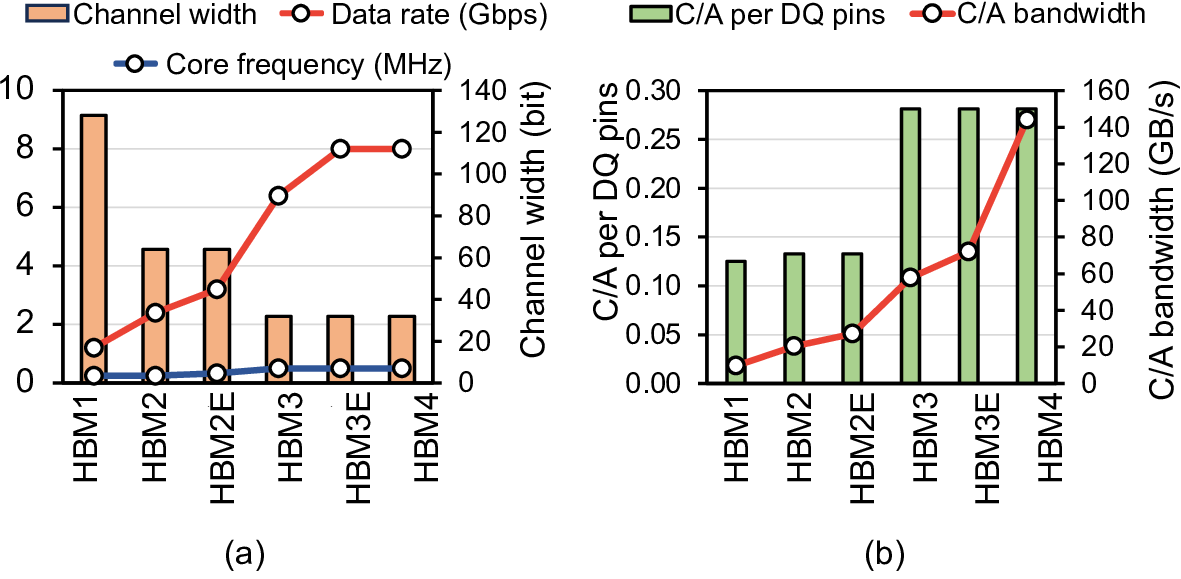

High bandwidth memory (HBM) has emerged as a key component of high-performance computing systems [28], [46]- [48] driving the transformer-based artificial intelligence (AI) proliferation [70]. The high bandwidth of HBM is required to keep pace with the compute capabilities of GPUs [48], [63], TPUs [16], [28], and other AI accelerators [14], [30], and satisfy the bandwidth-bound nature of the generation stages of the transformers [19], [55], [77]. A single cube of HBM4 [27] feeds 64 pseudo channels, each of which has 32 8 Gbps data pins, constituting a total of 2 TB/s bandwidth.

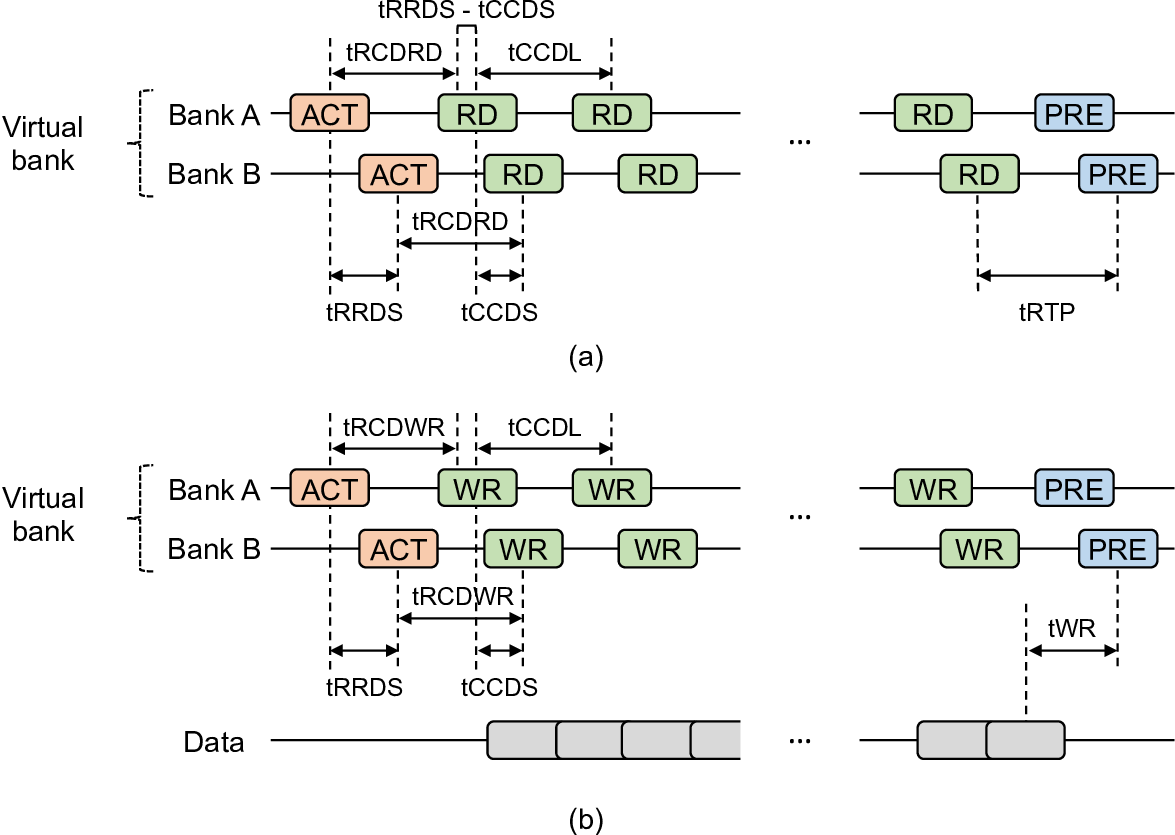

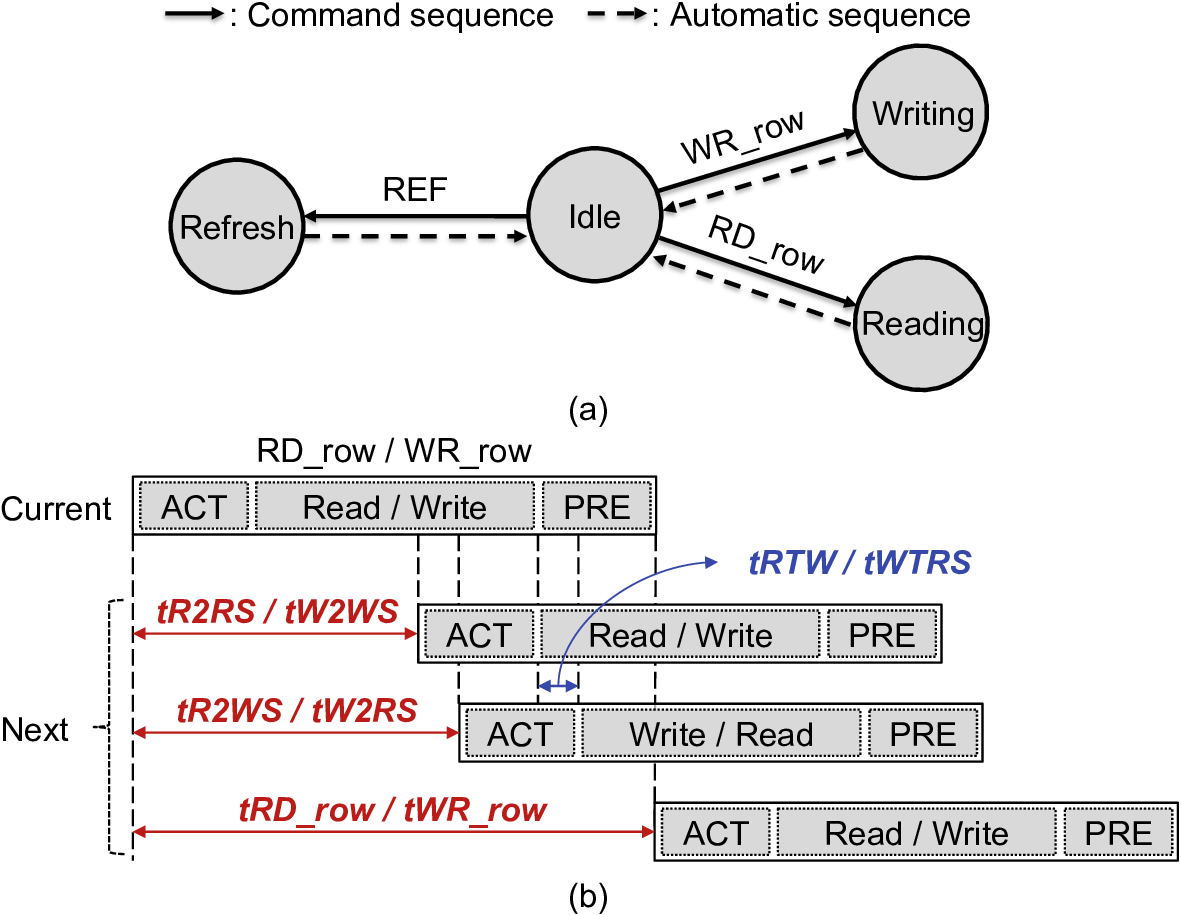

Saturating the immense HBM channel bandwidth requires efficient row-buffer utilization. A DRAM bank is composed of a 2-dimensional array of DRAM cells and indexed by row and column addresses. DRAM cell access latency is slow as it requires preceding precharge (PRE) and activation (ACT). This latency is too high to saturate such a huge channel bandwidth. To amortize those overheads, the bank prefetches an entire row into the row-buffer, which is orders of magnitude wider than the conventional DRAM access granularity. This strategy is highly effective in saturating the DRAM channel bandwidth when there exists a large spatial locality in the memory access pattern (e.g., streaming access). For example, when a series * Both authors contributed equally to the paper. of memory reads (RDs) target the same row-buffer, the processor-side memory controller (MC) can issue back-to-back RDs to saturate the channel bandwidth without the bubbles induced by ACT/PRE.

Instead of issuing multiple consecutive read commands, we ask: why can’t DRAM access granularity simply increase to match the row-level granularity in this scenario? However, memory access patterns vary, and increasing the minimum DRAM access granularity can cause overfetch problem by reading unnecessary data, degrading effective bandwidth [59]. Thus, conventional DRAM access granularity is set to match the cache line size of a processor (e.g., 32 B or 64 B).

Such a cache-line-sized access granularity complicates the memory controller (MC) architecture. To support column-level accesses (i.e., RDs/WRs), an MC must maintain bank states and timing parameters. Moreover, it must operate many banks in parallel to hide the latency overhead of ACT and PRE commands [3], [41], [60]. Further complexity arises from the need to determine when to issue PRE after ACT based on access patterns (i.e., the page policy [20], [60]).

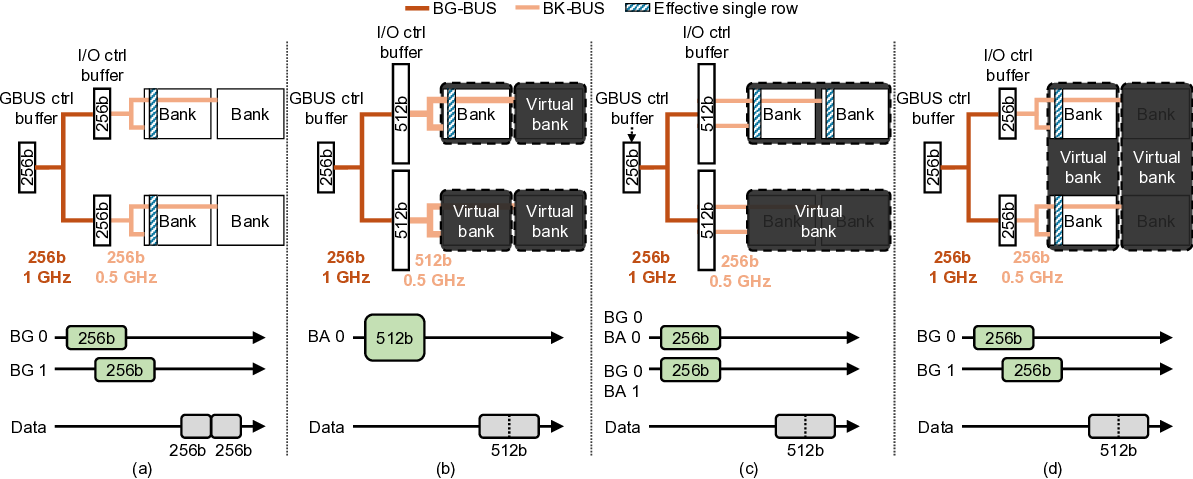

The HBM hierarchy also becomes increasingly complex due to the fine-grained access granularity. While HBM bandwidth has improved steadily [8], [27], [33], [56], the bandwidth per bank has remained nearly unchanged. As each bank operates at the DRAM core frequency and transfers data at a fixed access granularity, memory bandwidth can fundamentally be increased in only two ways: 1) by enlarging the access granularity or 2) by increasing the DRAM core frequency. However, the former is constrained by cache line size, and physical limitations prevent significantly increasing the latter.

To overcome these limits, additional hierarchical structures, such as bank group and pseudo channel (PC), were introduced to boost bandwidth [23], [24]. Bank groups combine multiple banks and deliver data to the I/O at a higher frequency, allowing transfers from different bank groups to overlap while maintaining cache line granularity. PCs increase the number of channels by reducing each channel’s width, improving bandwidth without increasing both DRAM core frequency and access granularity. Unlike previous generations, HBM4 doubles total bandwidth primarily by doubling I/Os (and thus PCs) without modifying the per-channel width. While effective in raising bandwidth, these mechanisms add significant complexity to memory controller scheduling and timing.

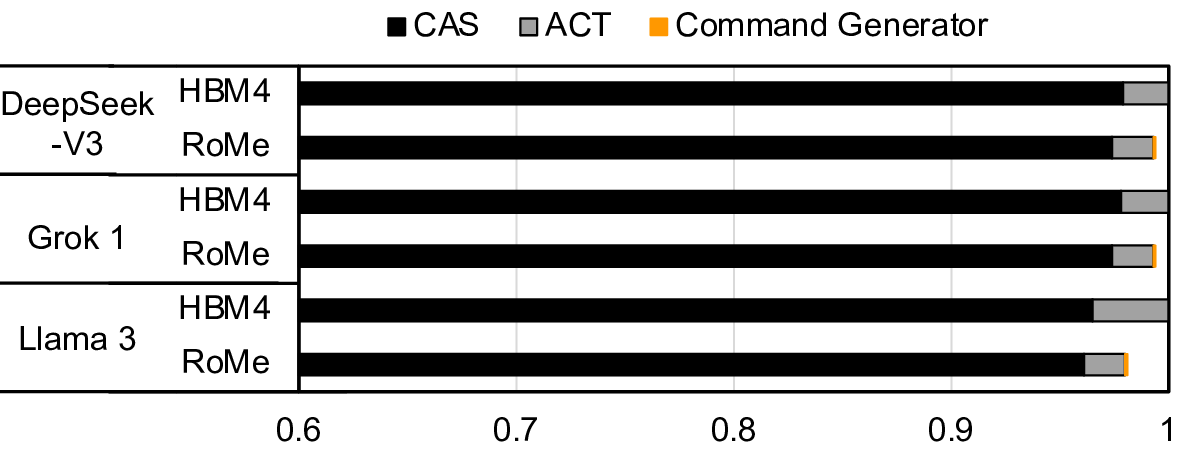

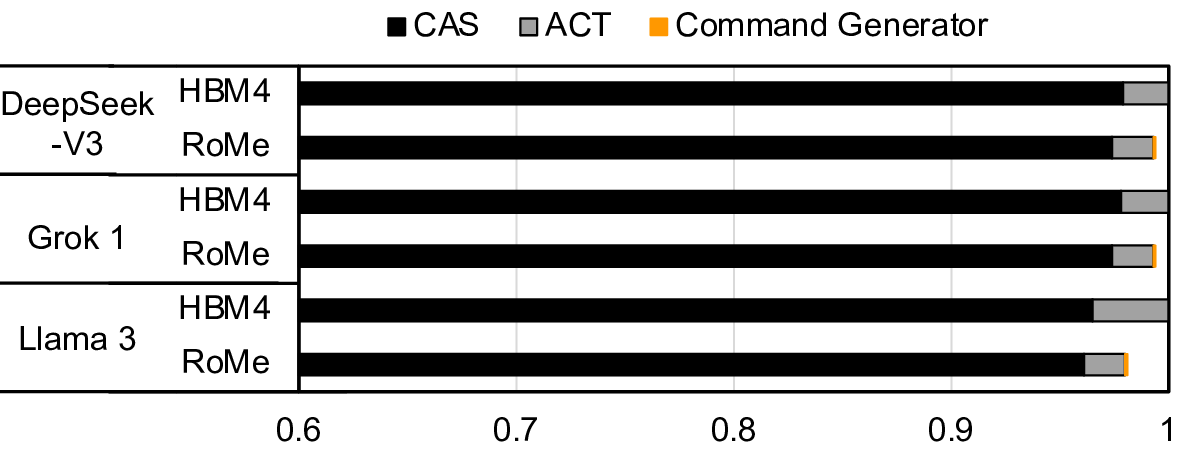

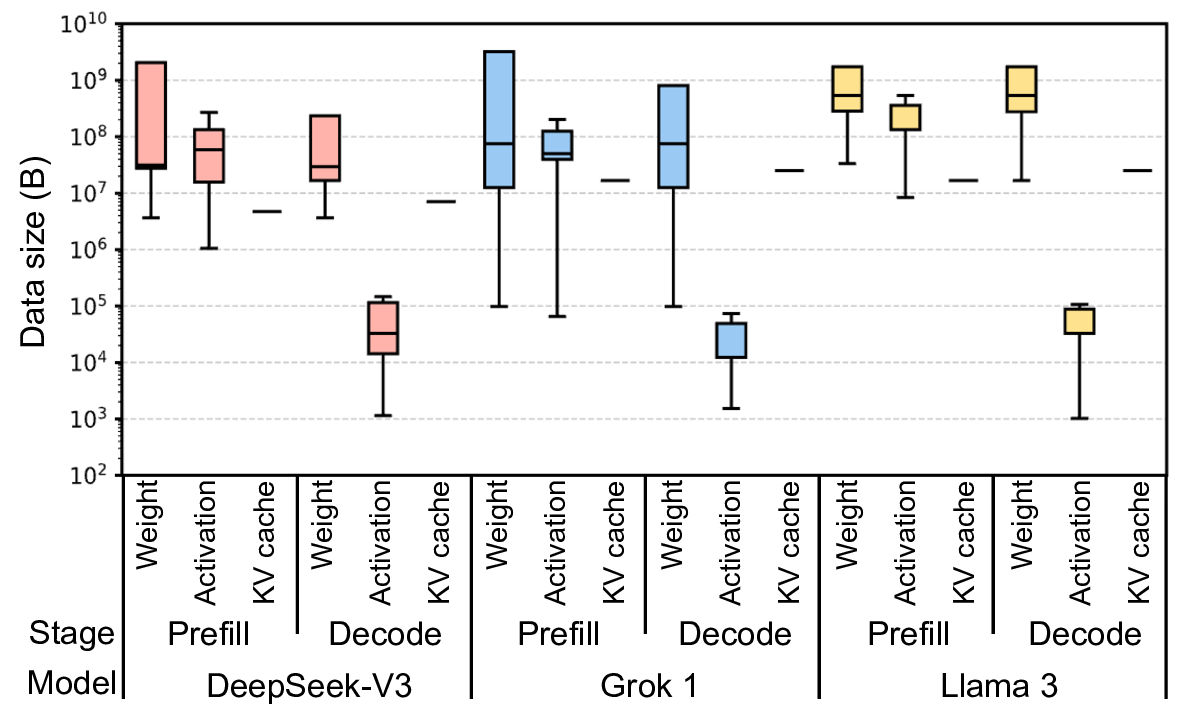

We challenge the need for such a conventional DRAM interface paradigm in the era of transformer-based Large Fig. 1. Distribution of weight, activation, and KV cache size of DeepSeek-V3 [12], Grok 1 [73], and Llama 3 [13] in the prefill and decode stages.

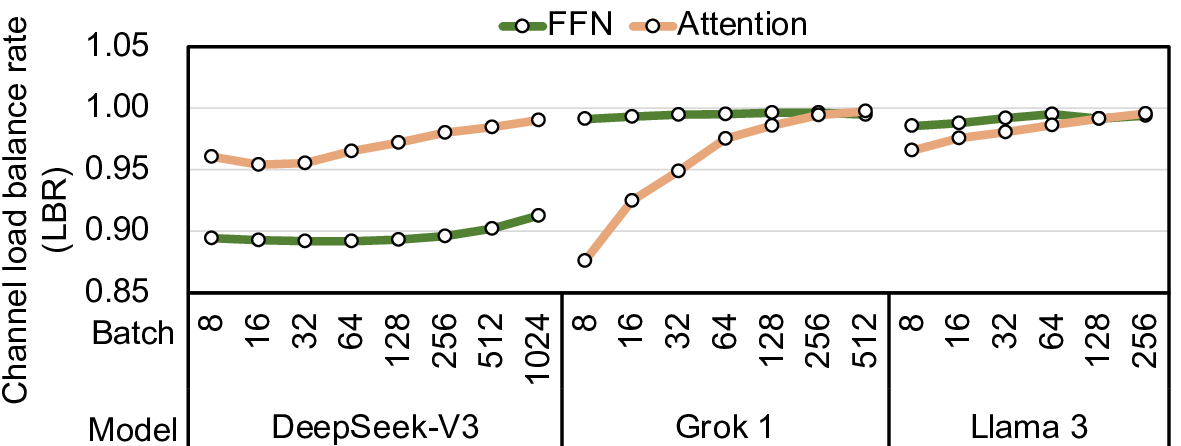

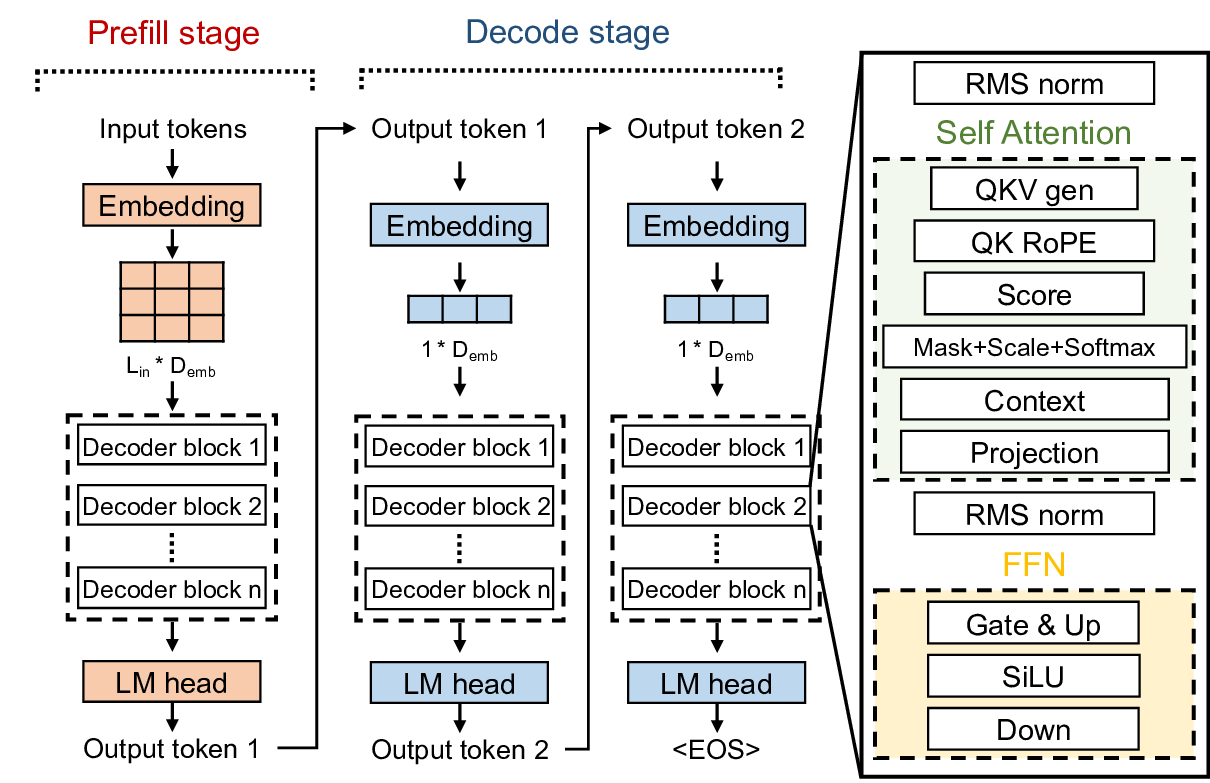

Language Models (LLMs). While traditional systems and data centers will persist, warehouse-scale systems running homogeneous applications of LLM inference (e.g., an AI factory [49]) are becoming widespread. LLMs mostly consist of simple general matrix-matrix or matrix-vector multiplication (GEMM/GEMV) and element-wise operations [55]. This is true even with state-of-the-art architectures, such as multi-head latent attention (MLA), grouped query attention (GQA), or mixture-of-experts (MoE) [37], [68], [73]. These models typically access tens of megabytes of data at once, far exceeding the size of conventional cache lines (Figure 1). Unlike the workloads with irregular or strided patterns, LLM operations exhibit highly sequential memory access patterns.

By exploiting the memory access patterns of LLMs, we propose RoMe, a Row-granularity-access Memory system designed to offer a simple and scalable me

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.