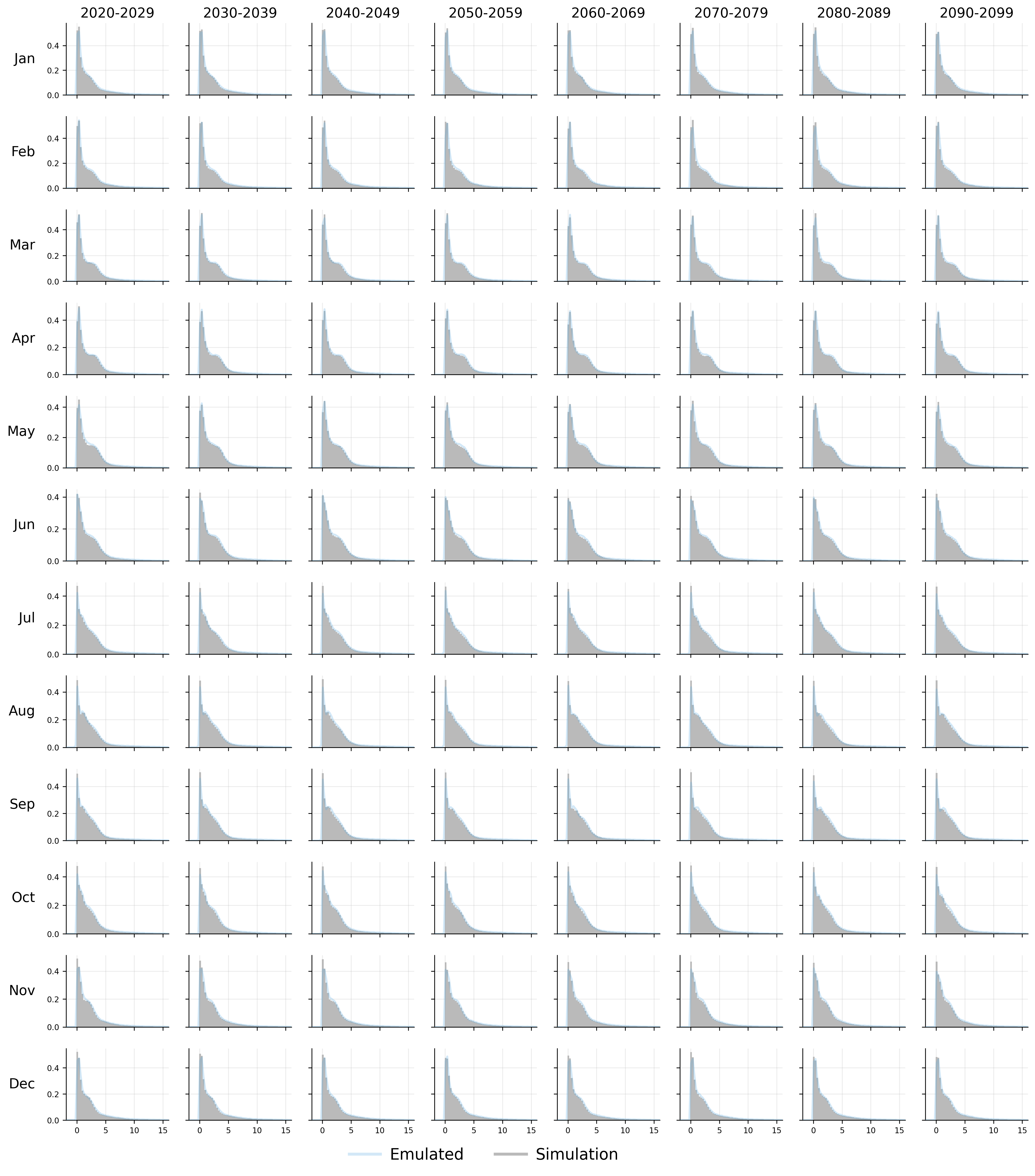

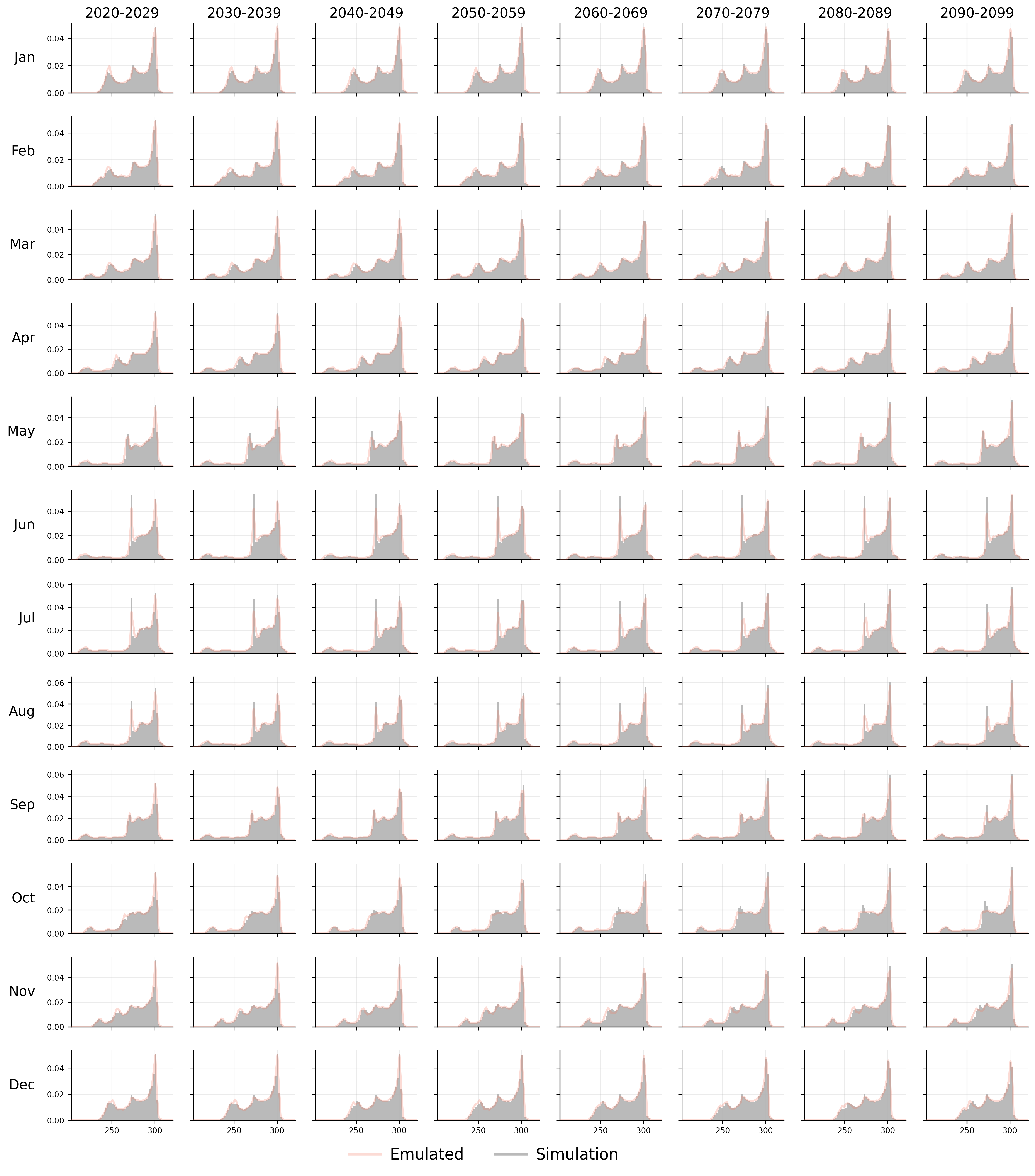

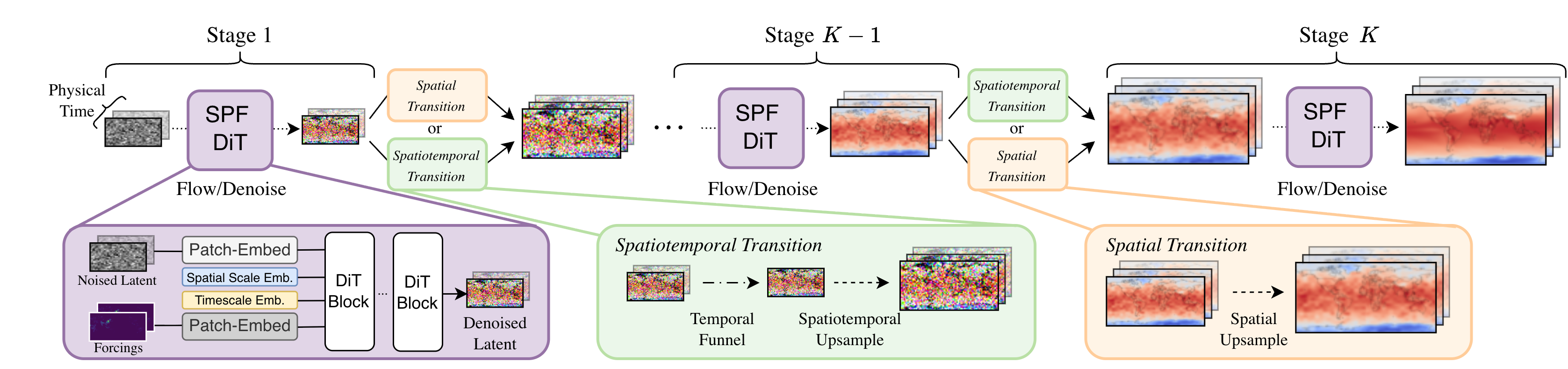

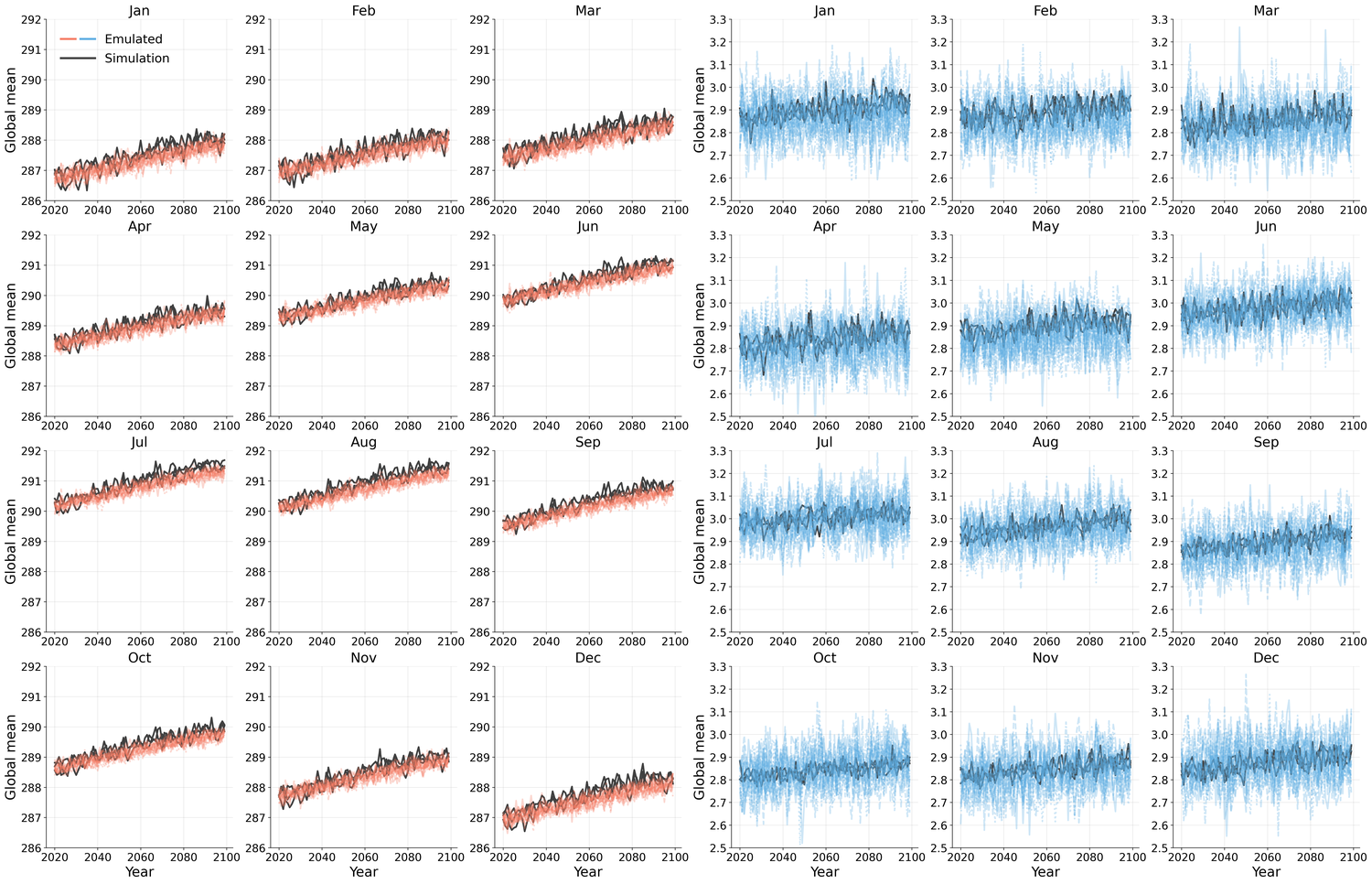

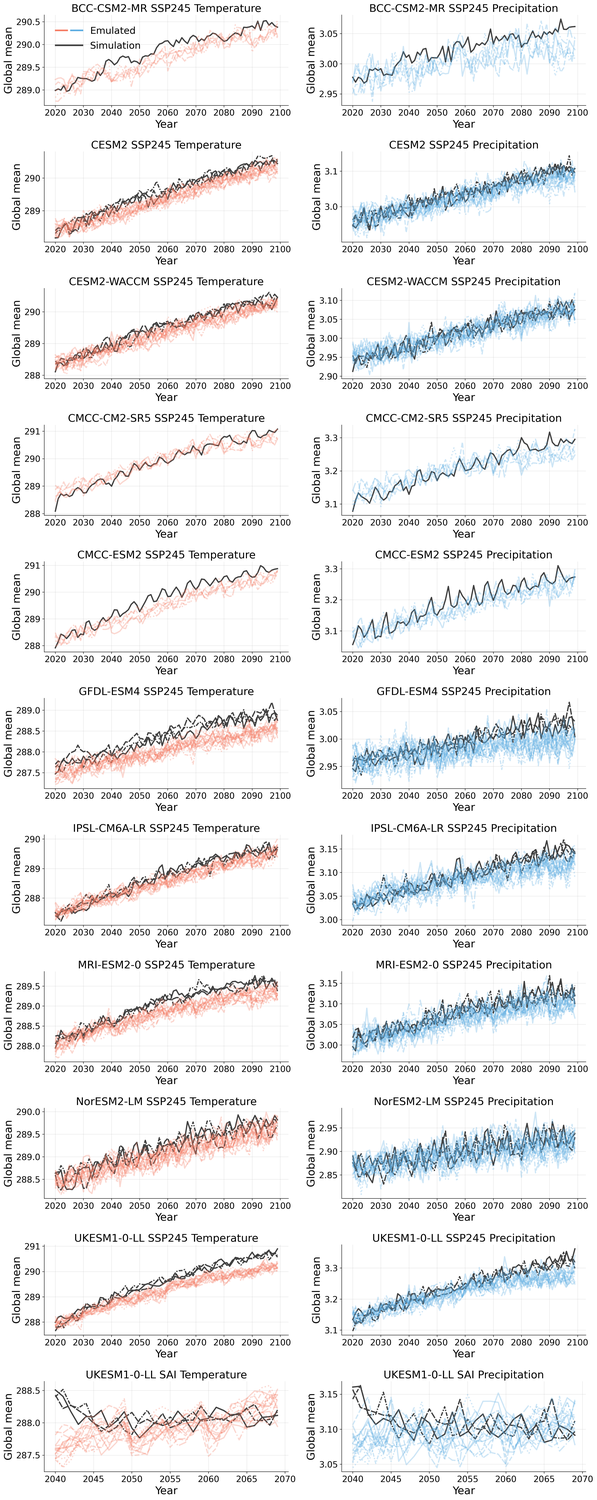

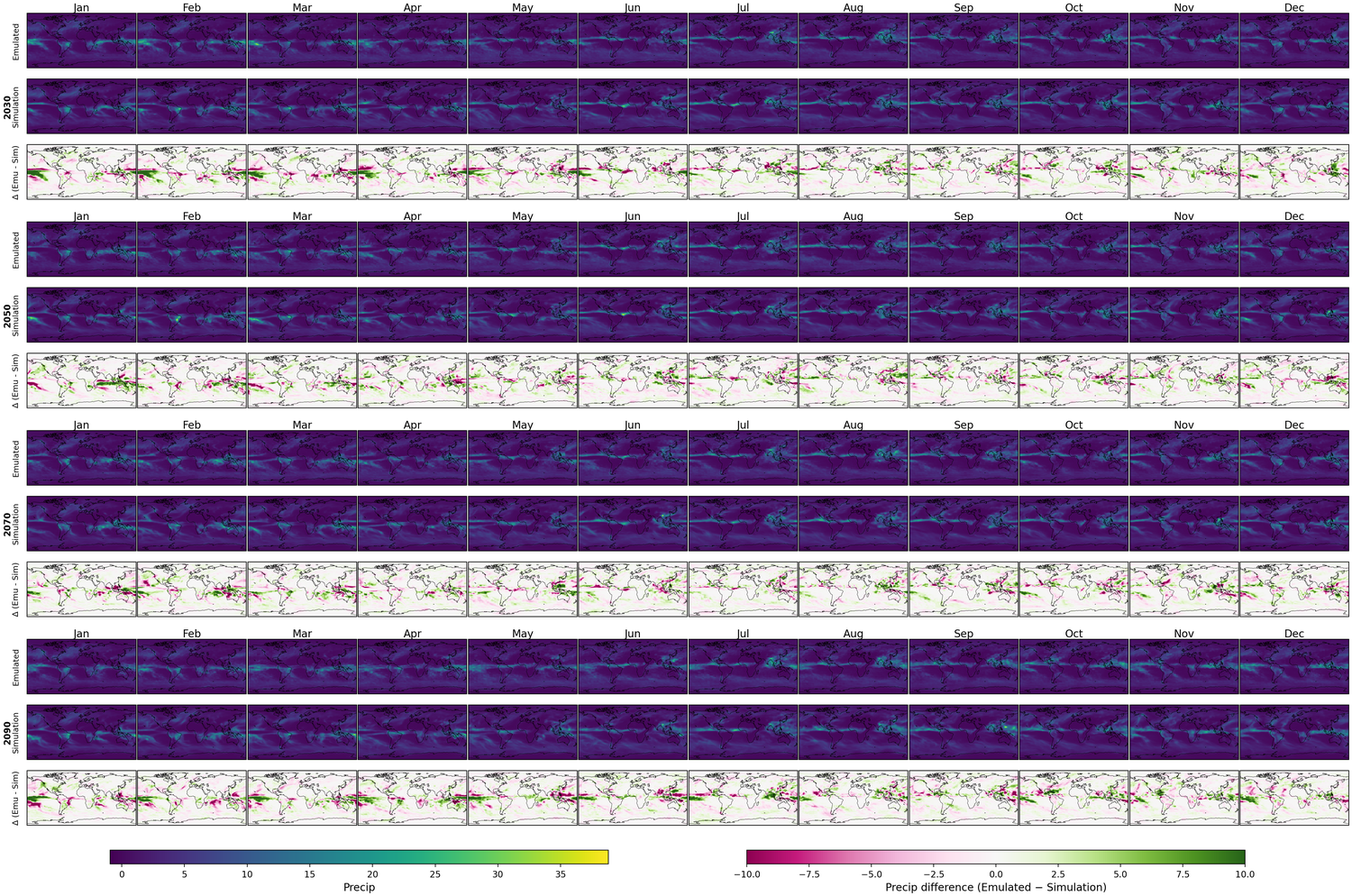

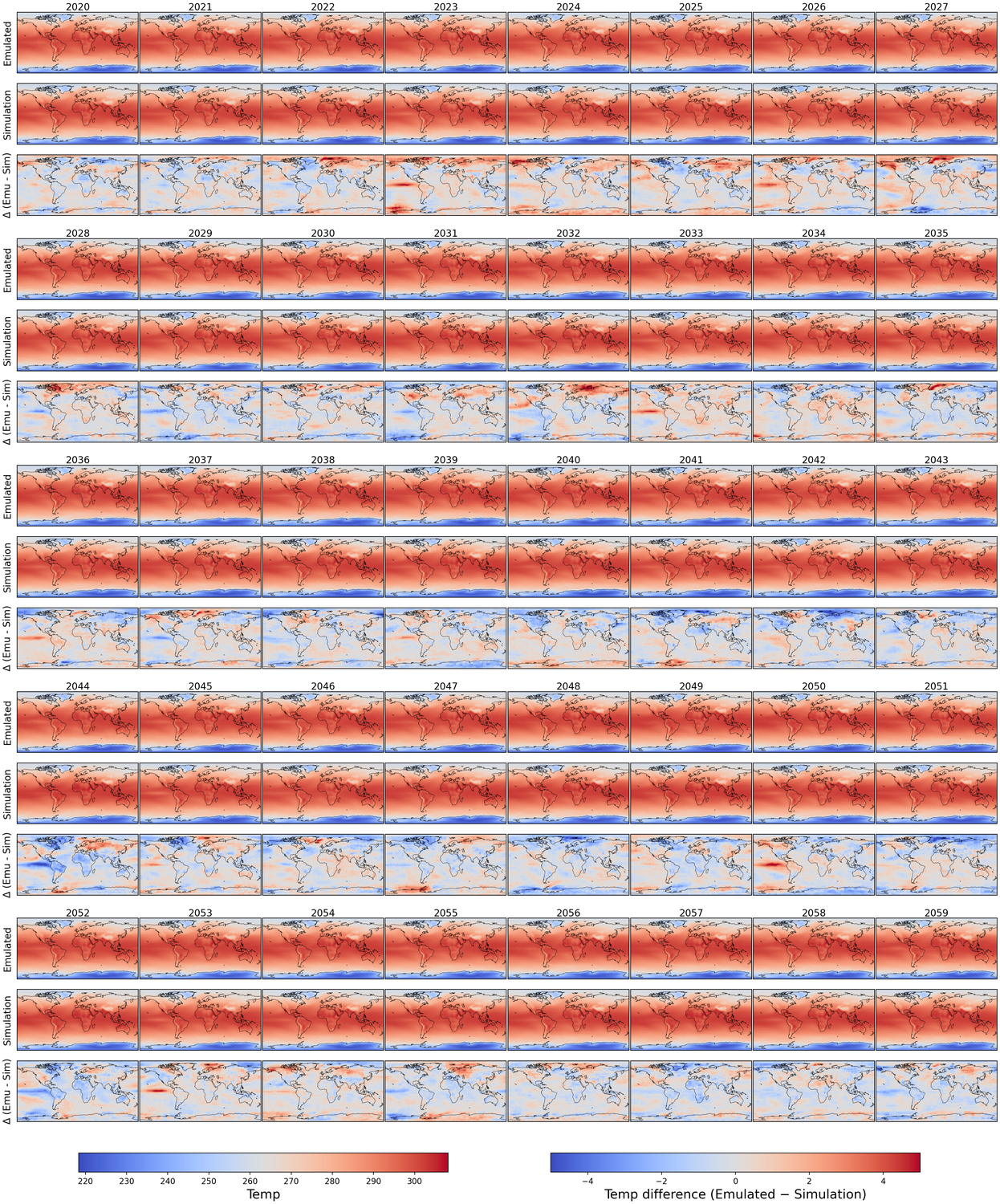

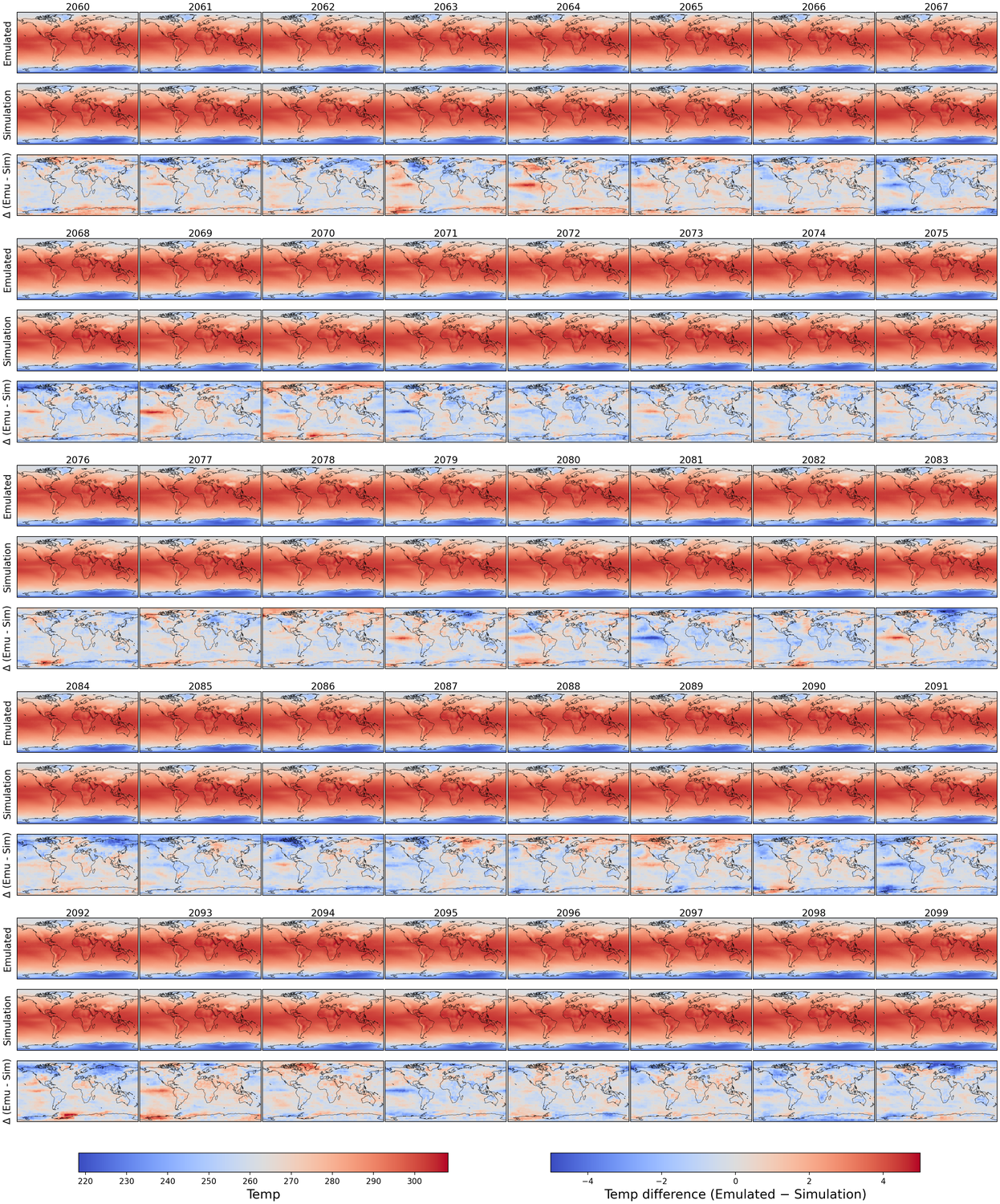

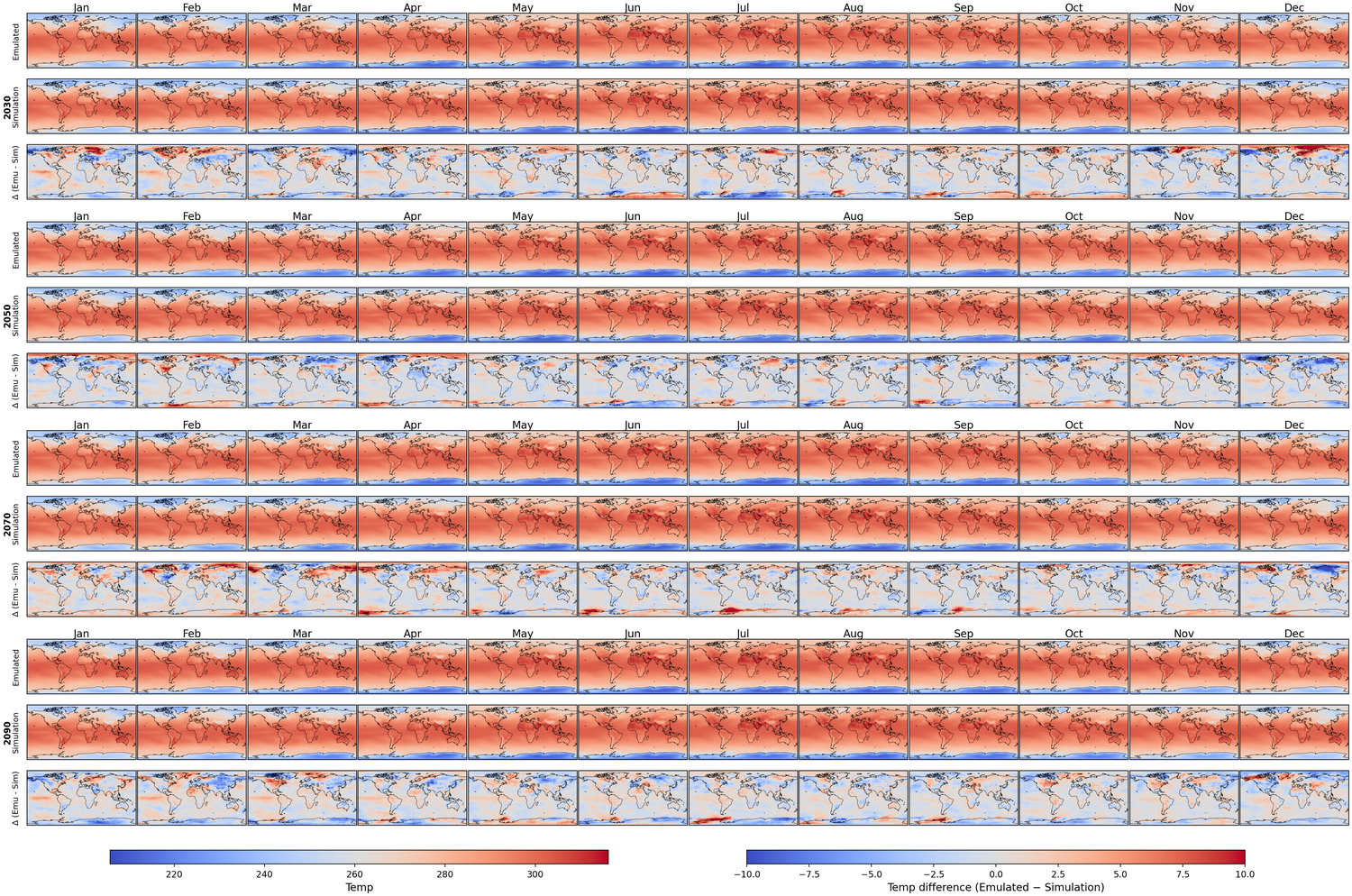

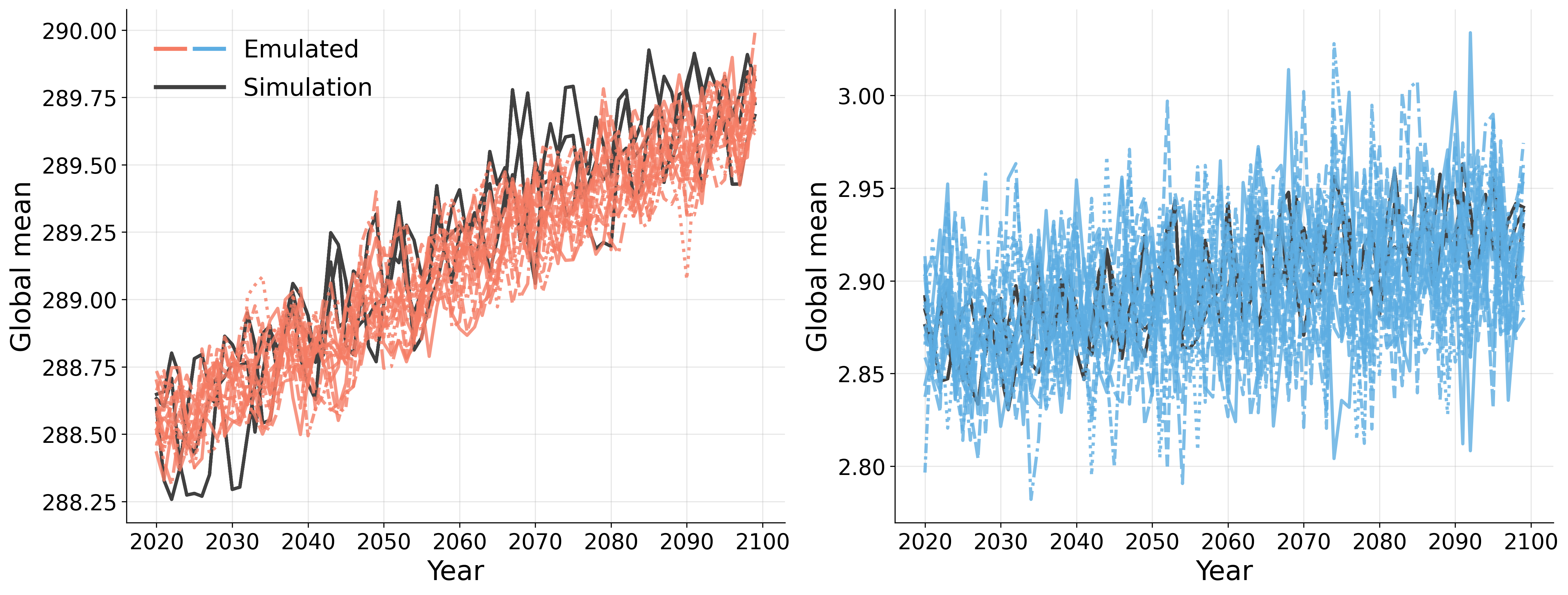

Generative models have the potential to transform the way we emulate Earth's changing climate. Previous generative approaches rely on weather-scale autoregression for climate emulation, but this is inherently slow for long climate horizons and has yet to demonstrate stable rollouts under nonstationary forcings. Here, we introduce Spatiotemporal Pyramid Flows (SPF), a new class of flow matching approaches that model data hierarchically across spatial and temporal scales. Inspired by cascaded video models, SPF partitions the generative trajectory into a spatiotemporal pyramid, progressively increasing spatial resolution to reduce computation and coupling each stage with an associated timescale to enable direct sampling at any temporal level in the pyramid. This design, together with conditioning each stage on prescribed physical forcings (e.g., greenhouse gases or aerosols), enables efficient, parallel climate emulation at multiple timescales. On ClimateBench, SPF outperforms strong flow matching baselines and pre-trained models at yearly and monthly timescales while offering fast sampling, especially at coarser temporal levels. To scale SPF, we curate ClimateSuite, the largest collection of Earth system simulations to date, comprising over 33,000 simulation-years across ten climate models and the first dataset to include simulations of climate interventions. We find that the scaled SPF model demonstrates good generalization to held-out scenarios across climate models. Together, SPF and ClimateSuite provide a foundation for accurate, efficient, probabilistic climate emulation across temporal scales and realistic future scenarios. Data and code is publicly available at https://github.com/stanfordmlgroup/spf .

Climate models (Earth system models; ESMs) are the primary scientific instruments for quantifying how the Earth's climate will evolve under changing emissions and interventions. They resolve interacting physical processes across a * Correspondence to: jirvin16@cs.stanford.edu wide range of spatial and temporal scales, but this fidelity comes with enormous computational cost: long rollouts (decades to centuries), ensembles for uncertainty quantification, and large design sweeps across forcings make systematic exploration prohibitive even on state-of-the-art supercomputers [14,16,26]. As a consequence, scientists and policymakers are constrained to a narrow set of scenarios and limited ensemble sizes, which hinders robust assessment of regional risks and of policy-relevant choices such as emissions pathways or climate interventions [30,40,54]. These pressures have led to increasing interest in datadriven surrogates that efficiently emulate ESMs while remaining accurate, stable, and physically plausible over very long horizons [5,54,56].

Recent work has made tangible progress toward this goal, but it has relied primarily on autoregressive emulation at the weather-scale (short term) rolled out over climatescale (long term) periods [5,28,56,57]. This approach inherits two central limitations for climate emulation: first, weather-scale autoregressive models are subject to small local errors that compound over time, leading to drift in longterm statistics. Although recent models have demonstrated decade-long rollouts with small climatological biases in a simplified atmospheric model with fixed forcings, they have yet to capture realistic climate trends driven by greenhouse gas emissions or aerosols [56,57]. Second, long-horizon rollouts remain computationally expensive due to the large number of sequential autoregressive steps; for example, generating a single 10-year trajectory with a state-of-theart emulator takes nearly three hours [5]. This is especially prohibitive for many practical downstream uses which only require coarser timescale samples, e.g., annual indicators for integrated assessment models and policy assessments, or monthly fields for sectoral impact studies [15,51]. In parallel, regression-based emulators that directly map external forcings to long-term mean climate responses offer an alternative path toward efficiency [39,54]. Our approach builds upon regression-based methods to capture multiple timescales within a single model and support parallel sampling of temporal sequences, leading to additional efficiency gains for long time horizons.

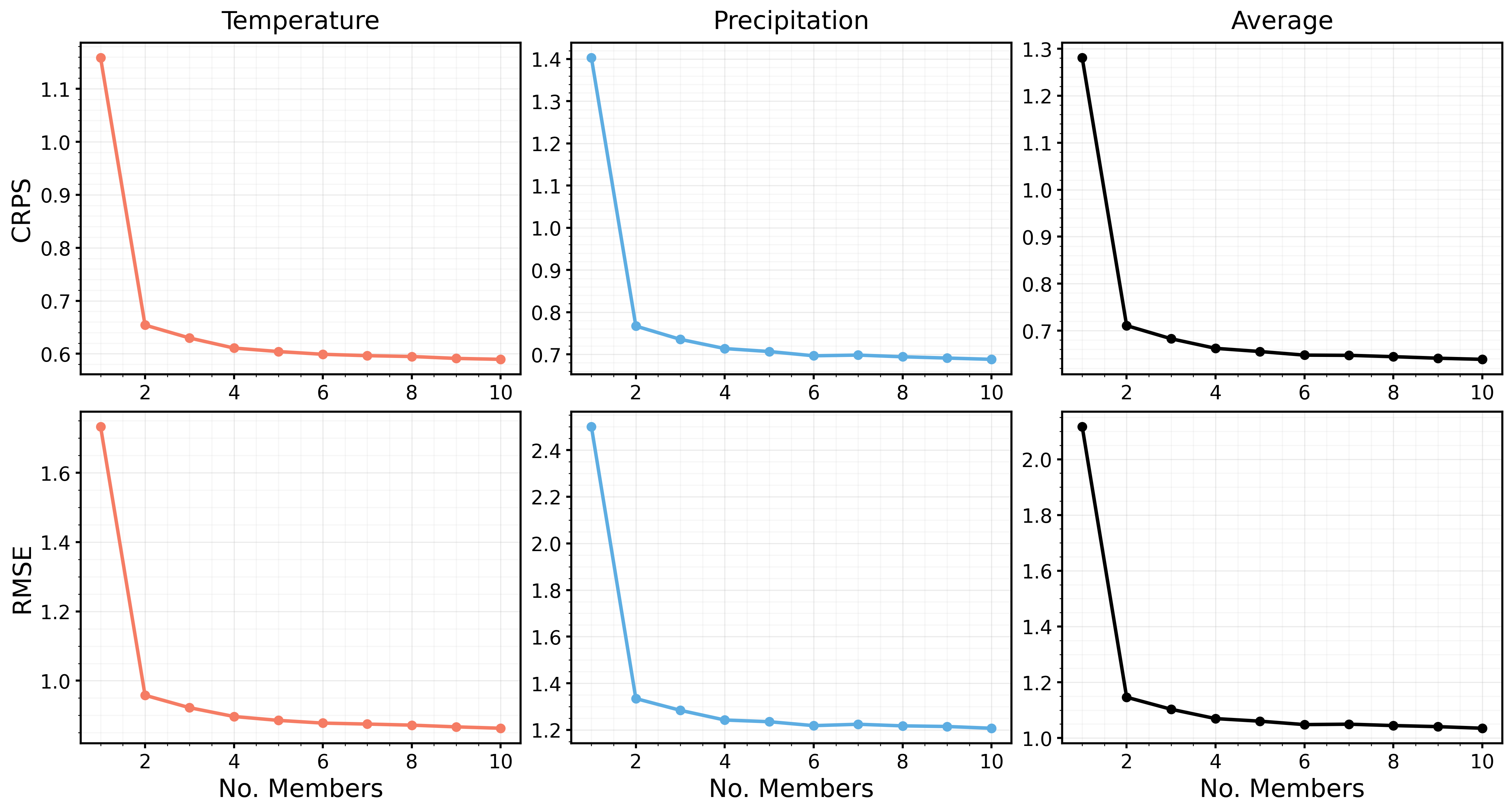

Beyond accuracy and efficiency, a critical requirement for climate emulation is the ability to represent uncertainty. In Earth system modeling, ensembles of simulations are used to quantify variability and assess the likelihood of climate outcomes. Similarly, probabilistic emulators should generate diverse samples from a learned distribution, allowing estimation of uncertainty and exploration of alternative trajectories under the same forcing conditions. Only recently has work begun to address this need by developing stochastic climate-scale emulators capable of sampling multiple plausible futures [3,5,28].

Diffusion and flow-based image and video generative models offer a promising path toward emulators that combine efficiency with probabilistic generation. These models provide a flexible framework for sampling from complex multimodal data distributions and have demonstrated remarkable success on image [20,32] and video generation tasks [23,24]. However, most high-quality video models (i) rely on autoregression through time to model long sequences, which scales poorly [7] and/or (ii) compress the high-dimensional spatiotemporal data into lowdimensional latents using a strong variational autoencoder (VAE), a component that is unavailable for climate data, difficult to train, and constrains performance to the quality of the learned compression [17,24,29,33,43]. We address these challenges with an efficient parallel approach operating in pixel space, eliminating the need for a separate VAE.

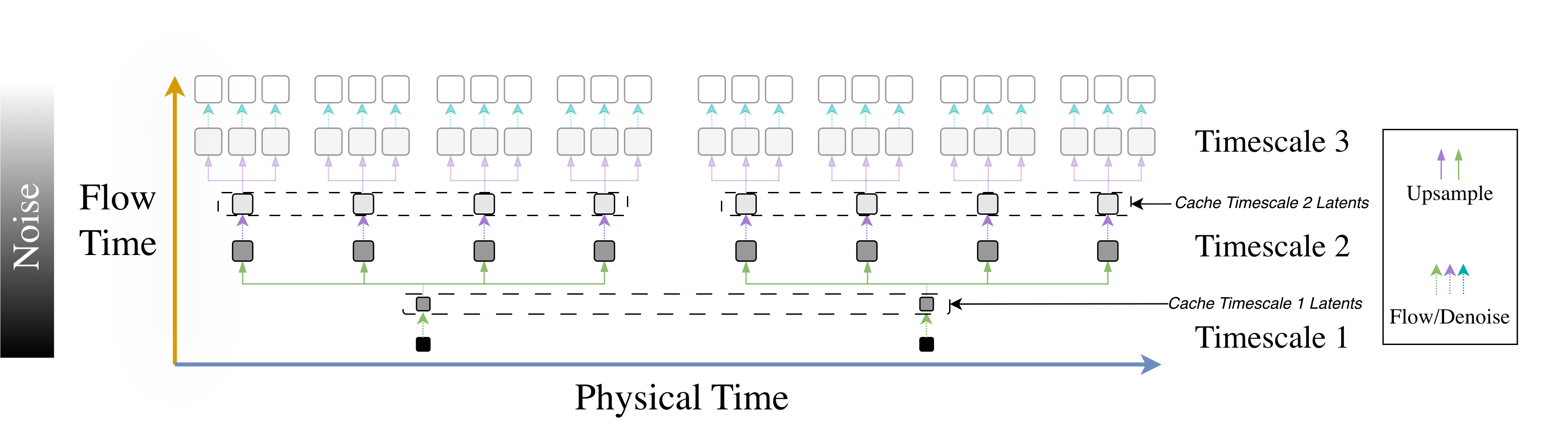

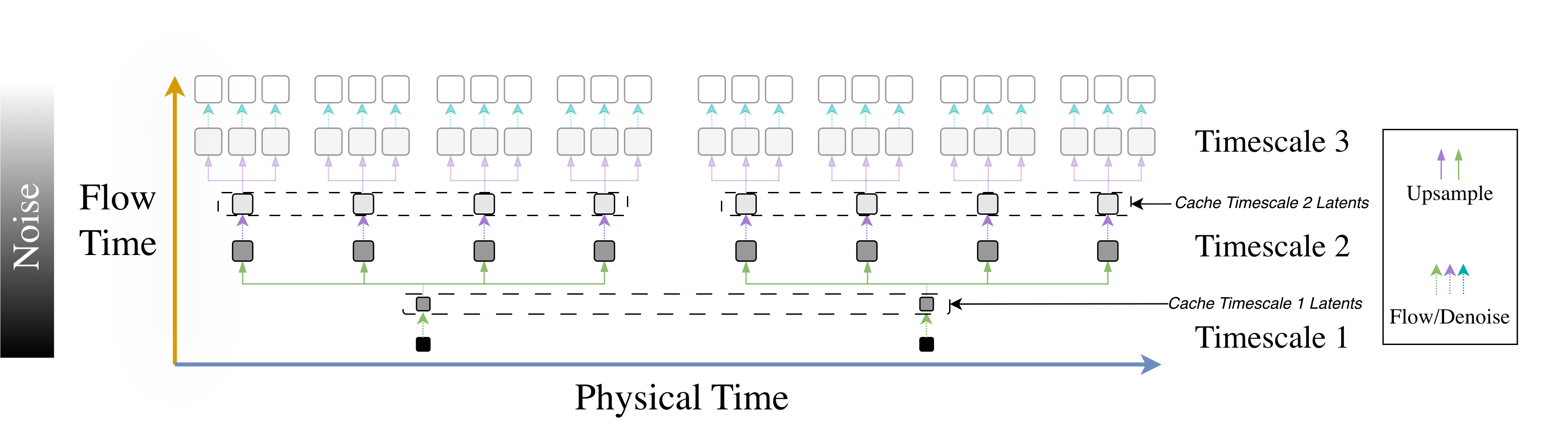

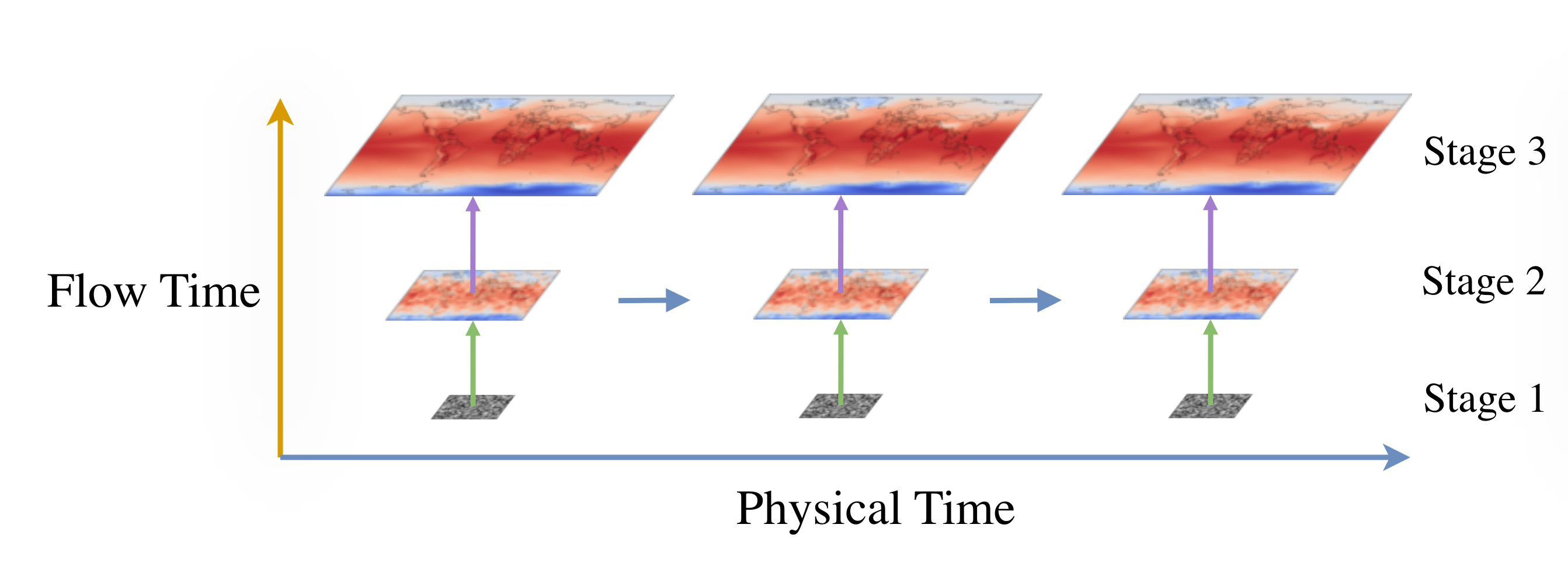

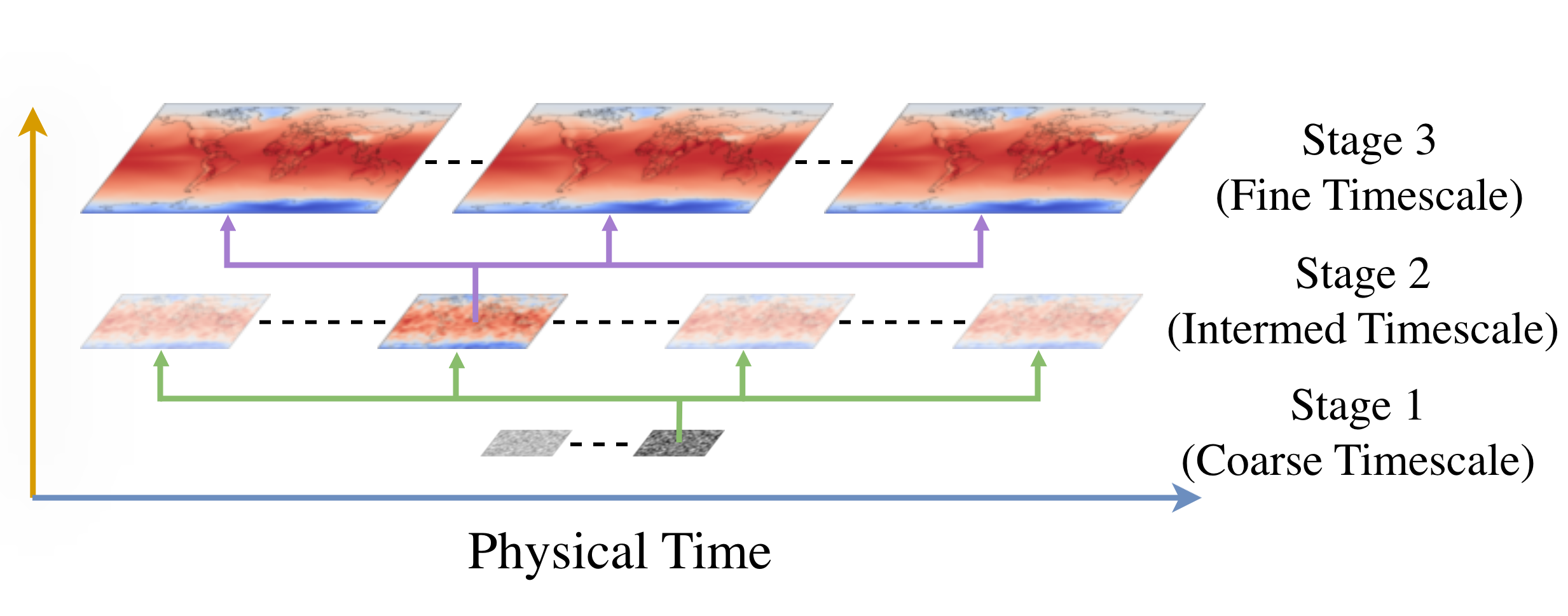

A key algorithmic insight from the natural image and video domains is to cascade generation: model coarse structure first and then refine in multiple stages, thereby concentrating compute where it most affects perceptual quality [22]. Recent work performs this cascade within a single model by partitioning the flow into stages at different spatial resolutions, yielding faster sampling and a lower memory footprint than a full-resolution flow while allowing knowledge sharing between stages [8,24]. For climate data, an analogous inductive bias exists in both space and time. Spatially, large scales organize small scales through energy and moisture transports; temporally, slow components such as forced trends and interannual variability modulate fast weather fluctuations. Rather than explicitly modeling these long-term dependencies through extended rollouts, conditioning the m

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.