Algorithmic reasoning -- the ability to perform step-by-step logical inference -- has become a core benchmark for evaluating reasoning in graph neural networks (GNNs) and large language models (LLMs). Ideally, one would like to design a single model capable of performing well on multiple algorithmic reasoning tasks simultaneously. However, this is challenging when the execution steps of algorithms differ from one another, causing negative interference when they are trained together.

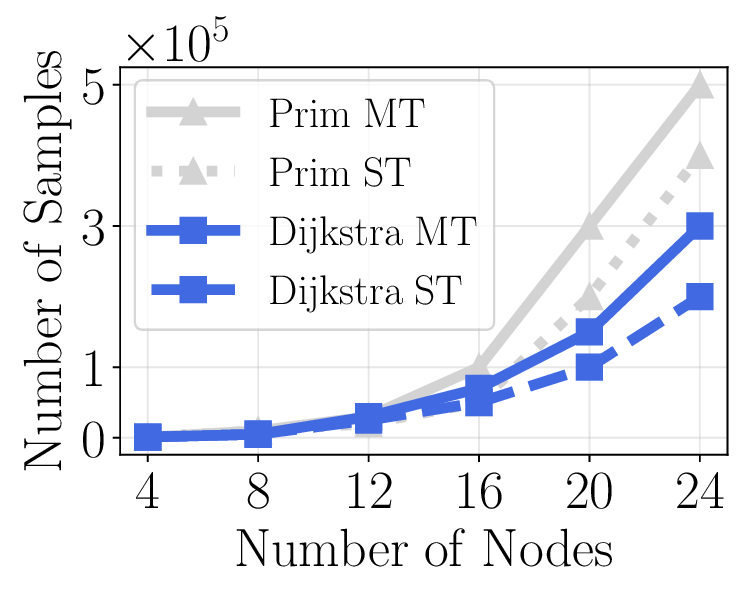

We propose branching neural networks, a principled architecture for multitask algorithmic reasoning. Searching for the optimal $k$-ary tree with $L$ layers over $n$ algorithmic tasks is combinatorial, requiring exploration of up to $k^{nL}$ possible structures. We develop AutoBRANE, an efficient algorithm that reduces this search to $O(nL)$ time by solving a convex relaxation at each layer to approximate an optimal task partition. The method clusters tasks using gradient-based affinity scores and can be used on top of any base model, including GNNs and LLMs.

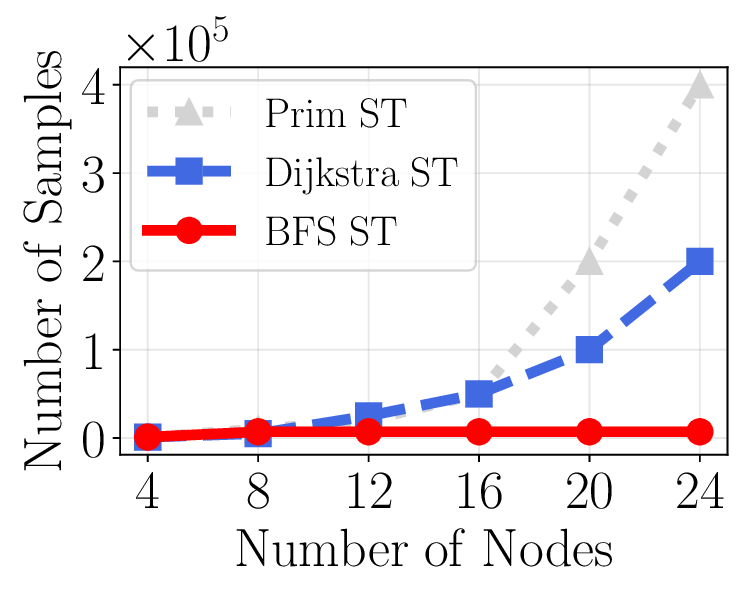

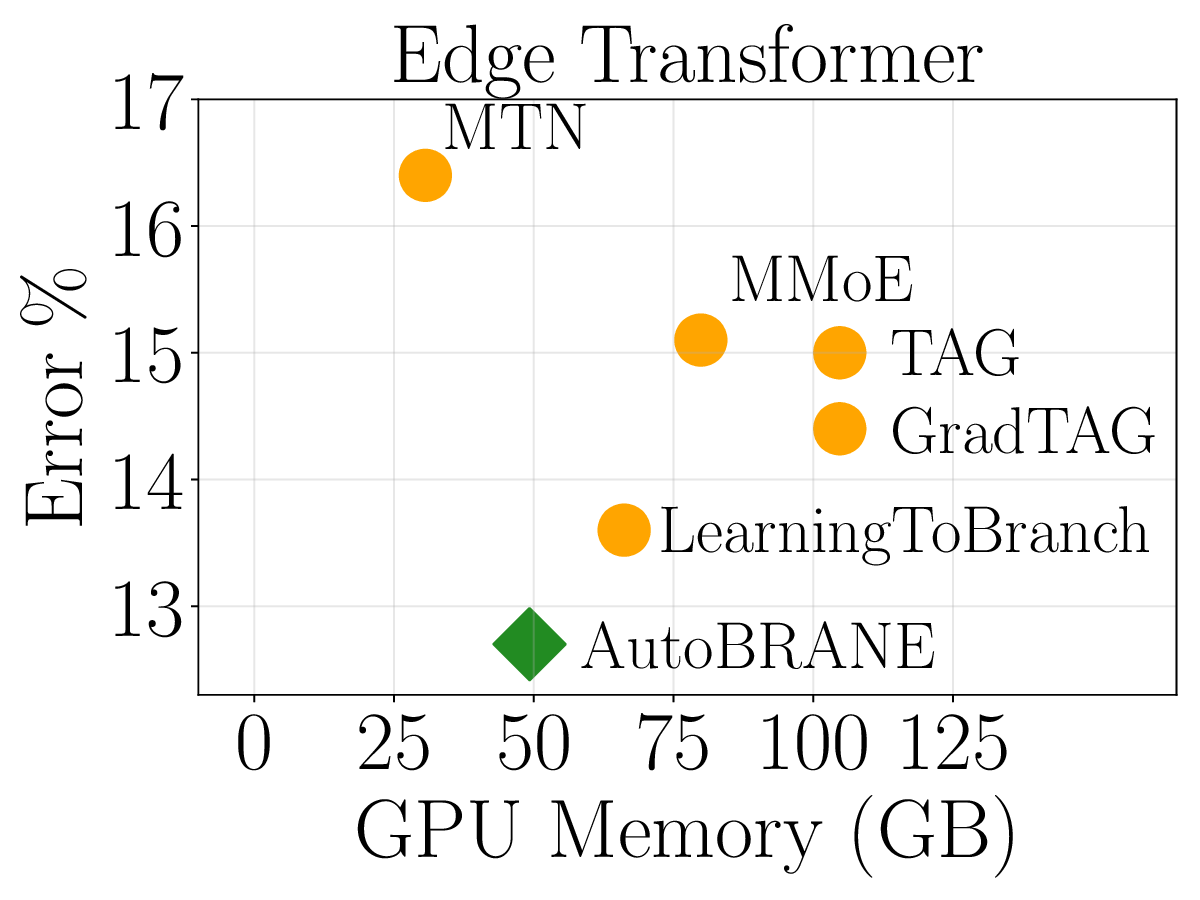

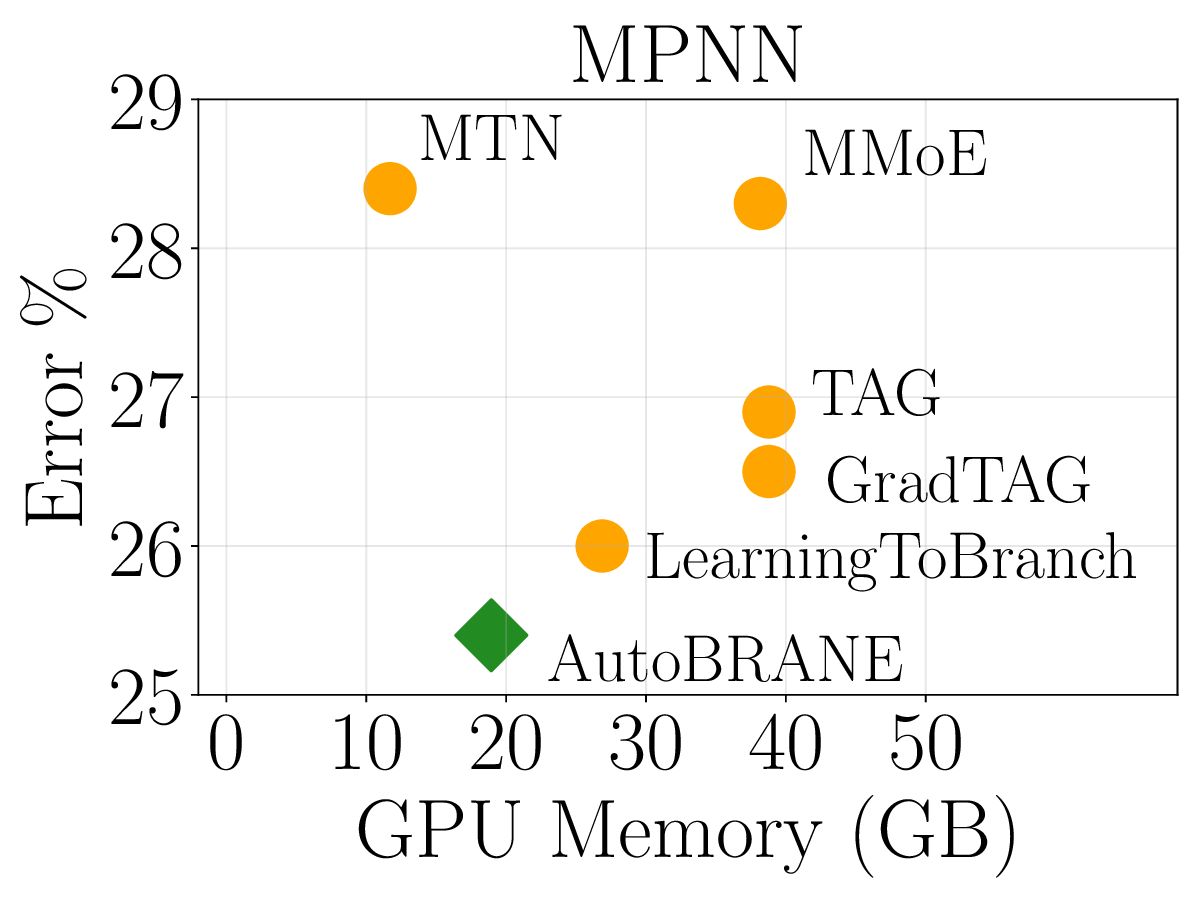

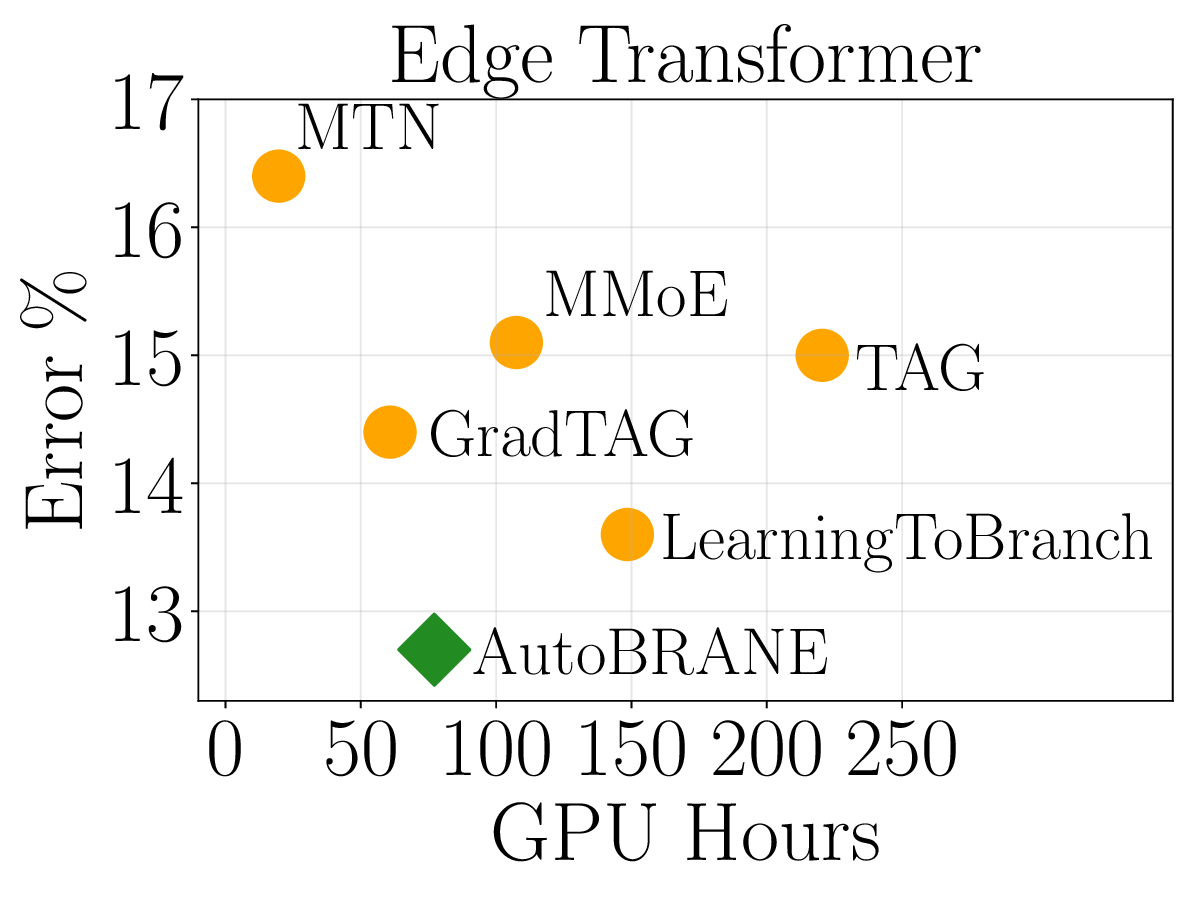

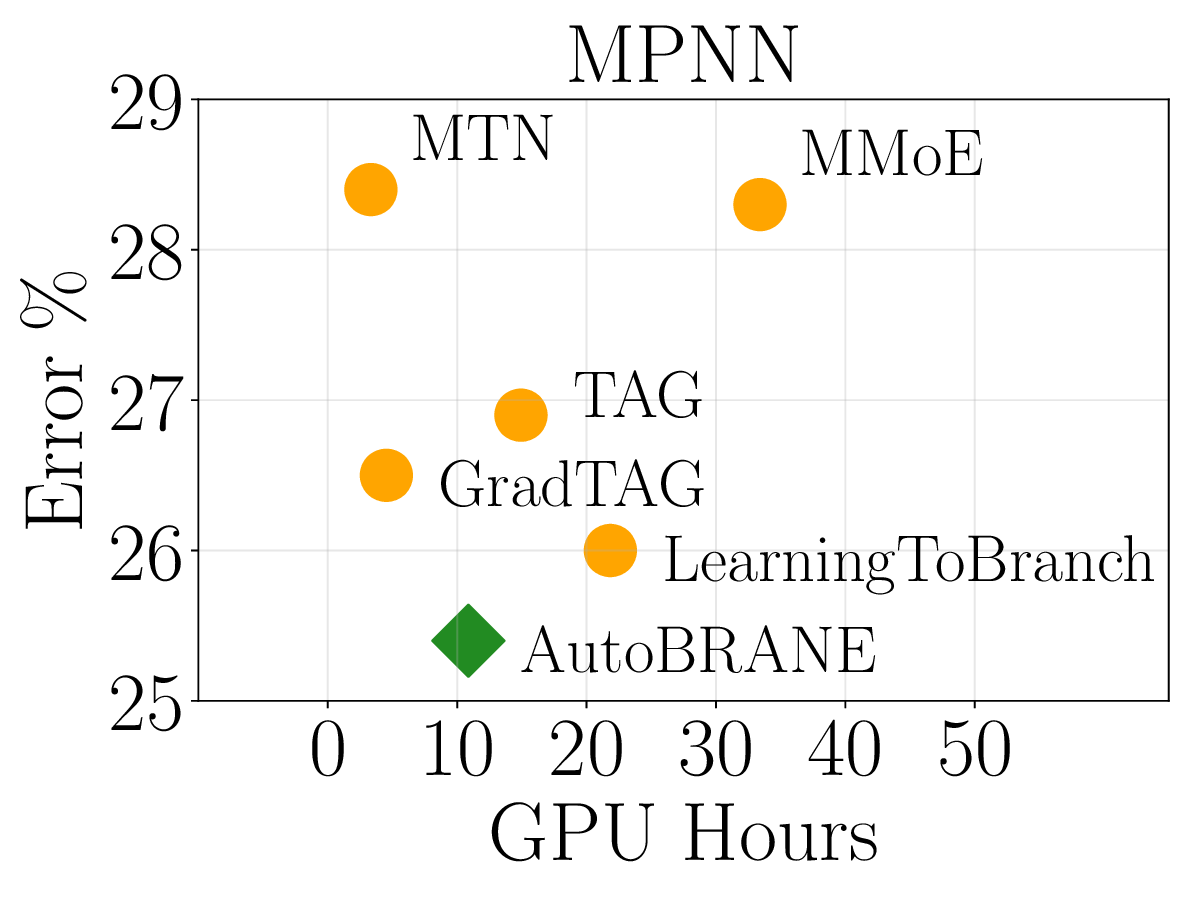

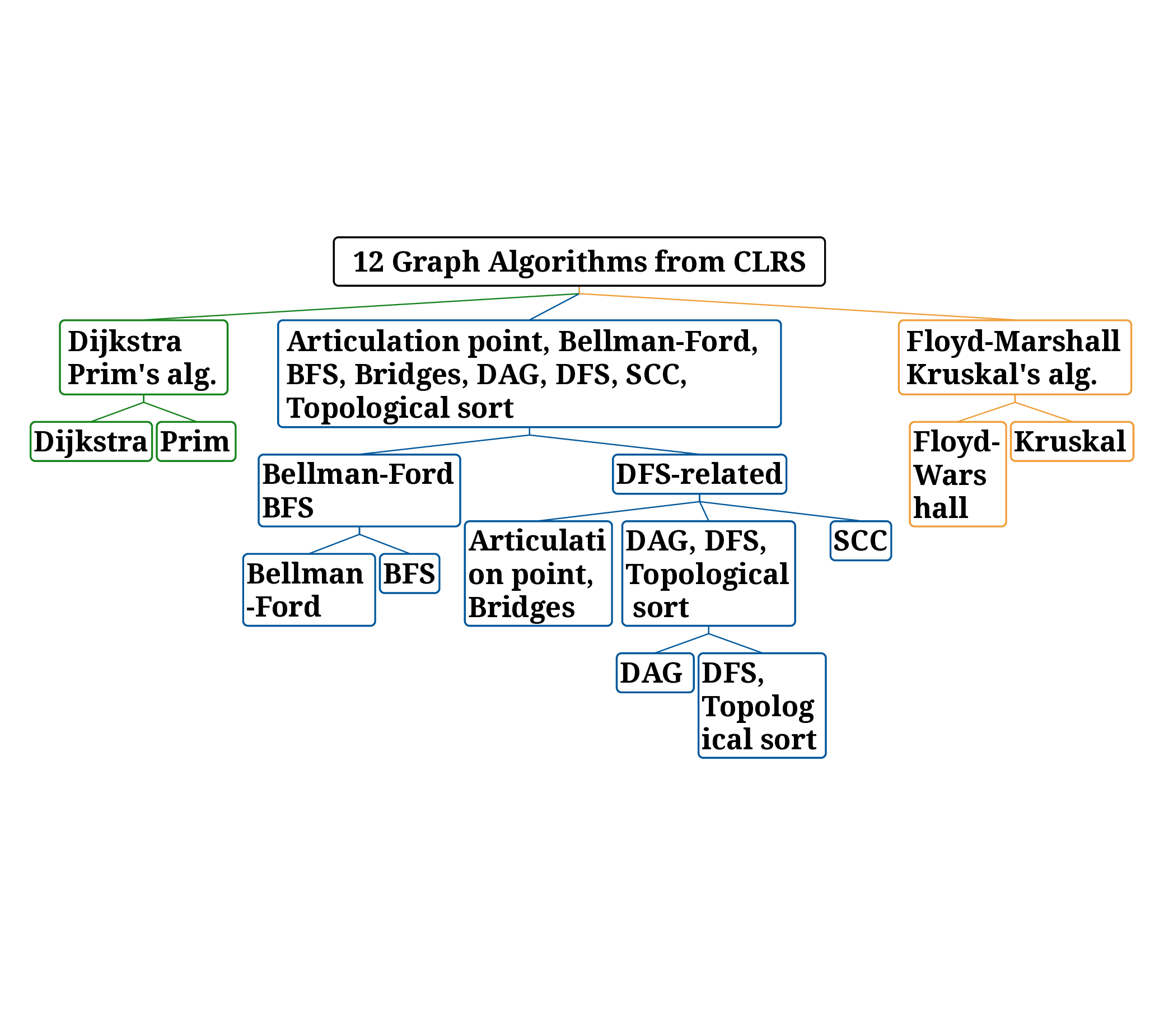

We validate AutoBRANE on a broad suite of graph-algorithmic and text-based reasoning benchmarks. We show that gradient features estimate true task performance within 5% error across four GNNs and four LLMs (up to 34B parameters). On the CLRS benchmark, it outperforms the strongest single multitask GNN by 3.7% and the best baseline by 1.2%, while reducing runtime by 48% and memory usage by 26%. The learned branching structures reveal an intuitively reasonable hierarchical clustering of related algorithms. On three text-based graph reasoning benchmarks, AutoBRANE improves over the best non-branching multitask baseline by 3.2%. Finally, on a large graph dataset with 21M edges and 500 tasks, AutoBRANE achieves a 28% accuracy gain over existing multitask and branching architectures, along with a 4.5$\times$ reduction in runtime.

Reasoning is tied to the ability of a learning system to make inductive inferences based on its internally stored states, and it remains one of the central challenges in artificial intelligence [6]. Many formalisms-most notably probabilistic reasoning via Bayesian networks-have been developed to build models that can reason efficiently under uncertainty [34]. More recently, a complementary Step 2:

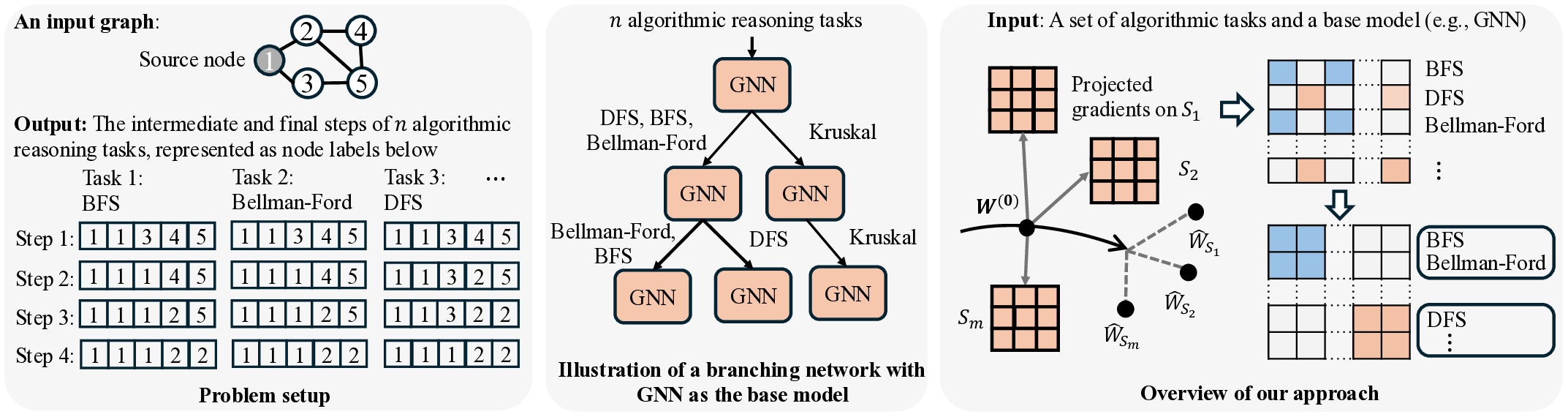

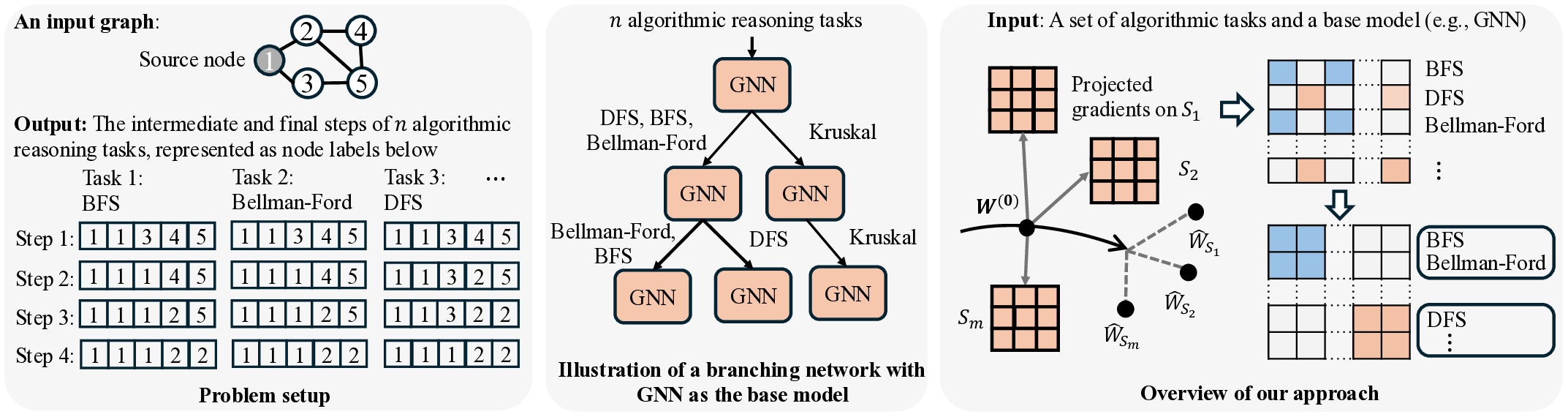

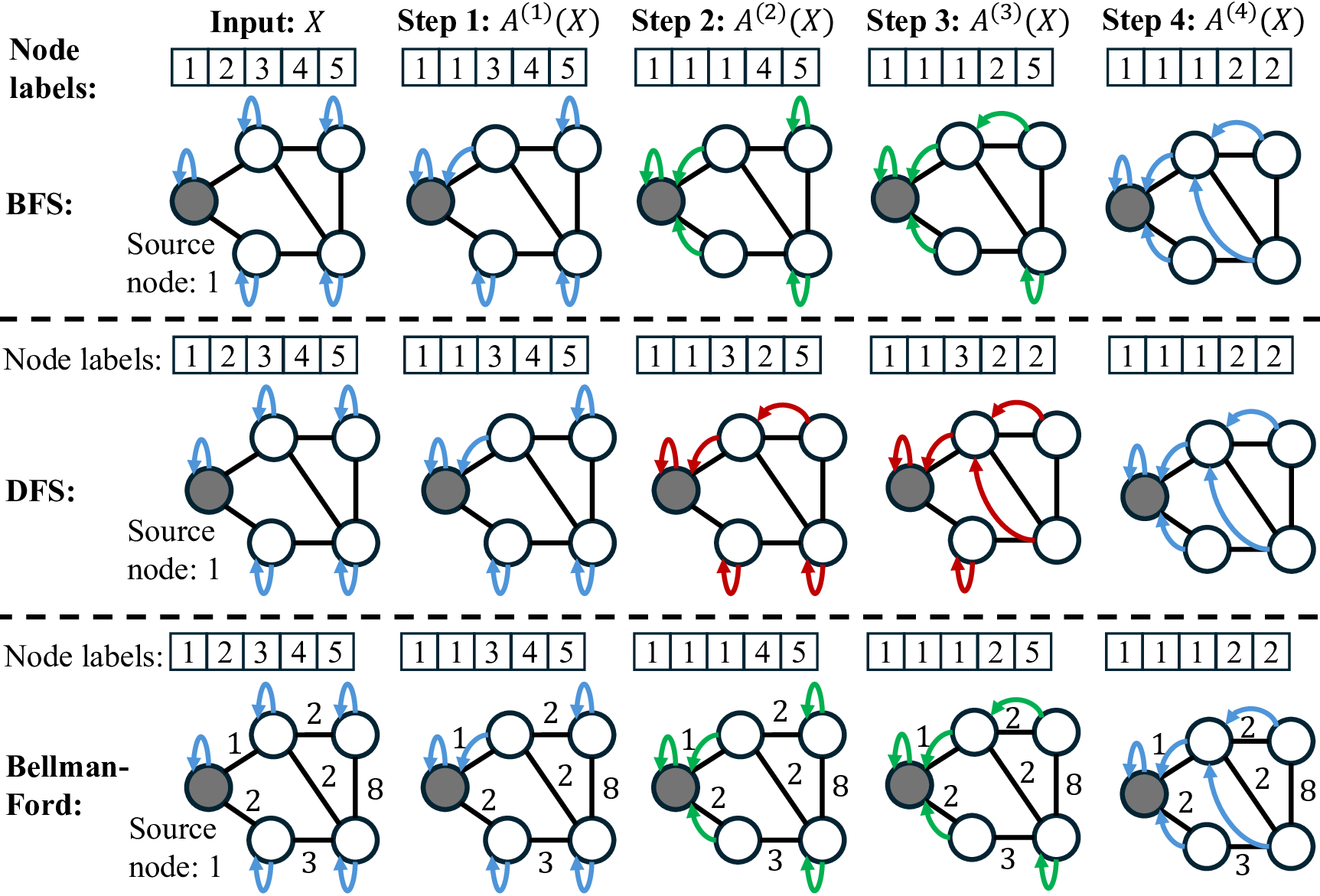

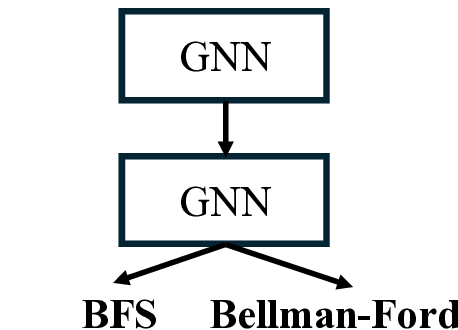

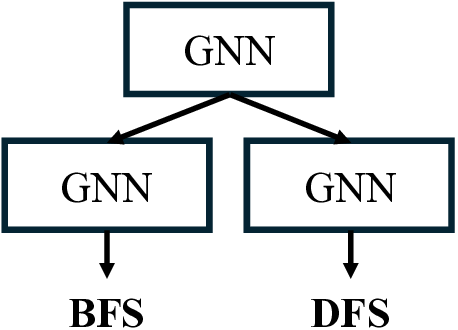

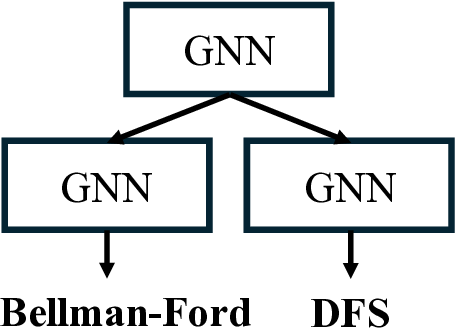

Step 3: Left: We study learning graph algorithms such as BFS, Bellman-Ford, and DFS, formulating the prediction of intermediate algorithmic states as a node-labeling classification problem. Center: Given n algorithmic reasoning tasks and a base model (e.g., GNNs or low-rank adapters), we develop an efficient method to construct a branching network that automatically learns parameter-sharing structures across all tasks. Right: Our algorithm identifies a task partition at each layer and then searches for a corresponding tree structure over layers 1, 2, . . . , L. Overall, the procedure runs in time O(nL)-dramatically faster than the naive worst-case of O(2 nL ).

line of work has sought to characterize the reasoning ability of neural networks through the lens of algorithmic execution, viewing reasoning as the step-by-step computation performed by a classical algorithm. Surprisingly, for a wide range of basic graph algorithms such as shortest paths and reachability, neural networks can be trained to accurately predict not only the final output of the algorithm but also its intermediate states [40]. This raises a natural next question: can we design a model capable of solving multiple algorithmic reasoning tasks simultaneously? Since the number of possible combinations among n tasks grows combinatorially, the central challenge becomes developing architectures and training methods that enable efficient and scalable multitask algorithmic reasoning.

A rigorous study of algorithmic reasoning is valuable not only from a foundational perspective [41], but also for its potential to improve the reasoning abilities of large language models (LLMs), especially on tasks involving graphs and structured computation [5,45,35]. In our own experiments, we observe that prompting open-source LLMs (e.g., Llama-3-8B and Qwen-3-1.7B) with textual descriptions of algorithmic tasks, such as shortest paths, performs roughly 65% worse than directly training a graph neural network on the same task. Besides, the ability to accurately predict intermediate algorithmic execution steps can also be linked to reasoning in chain-of-thought fine-tuning [30,44,3].

Several existing works have sought to design neural networks for tackling a single algorithmic reasoning task, while the problem of multitask algorithmic reasoning has not been studied in depth. Veličković et al. [40] introduce CLRS-30, a dataset of 30 algorithmic tasks, and find that message-passing neural networks can learn to accurately predict both the intermediate and final steps of a graph algorithm (where a graph is sampled from a fixed distribution). In particular, each intermediate step is treated as a node labeling sub-task, and the loss objective sums over all the intermediate node labeling sub-tasks (cf. equation (1), Section 2 for the definition). Consider breadth-first search (BFS) as an example (See also Figure 1 for an illustration). Starting from a graph and a source node to conduct the search, at each intermediate step, a network is trained to predict the index of the predecessor node in the current traversal path from the source. Ibarz et al. [13] conduct multitask experiments by training a single network across all CLRS-30 tasks, noting both positive and negative transfer compared to single-task training. Müller et al. [29] design a tri-attention mechanism in graph transformers, and use this new architecture to improve algorithmic reasoning over existing graph neural networks. Both works leave open the question of designing specialized optimizers for multitask algorithmic reasoning.

A key insight of this paper is that training a single neural network for multitask algorithmic tasks is inherently difficult due to complex interference between the intermediate steps (or node labels) of different algorithms. For example, in Figure 1, on a toy graph example, we notice that BFS and Bellman-Ford share the same intermediate node labels, while depth-first search (DFS) differs in Steps 2 and 3. However, if we use a single processor to predict all three tasks, this interference is unavoidable (See our study in Figure 6, Section 4.4). On the other hand, training a separate network for each task requires storing n models. This increases the memory at inference by n times, since n networks need to be evaluated.

To address this challenge, we explore the design of branching networks for multitask algorithmic reasoning by dividing algorithms into separate branches, taking into account their similarities. Searching over an L-layer, k-ary branching network for n tasks takes O(k nL ) time

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.