SOCs and CSIRTs face increasing pressure to automate incident categorization, yet the use of cloud-based LLMs introduces costs, latency, and confidentiality risks. We investigate whether locally executed SLMs can meet this challenge. We evaluated 21 models ranging from 1B to 20B parameters, varying the temperature hyperparameter and measuring execution time and precision across two distinct architectures. The results indicate that temperature has little influence on performance, whereas the number of parameters and GPU capacity are decisive factors.

In language models based on deep neural networks, parameters correspond to the values learned during training, such as weights and biases that transform input signals across layers 1 . The number of parameters determines the model's representational capacity: larger architectures capture more complex linguistic relationships but require more computational resources and present a higher risk of overfitting.

Hyperparameters are defined before training or during inference, and they influence both the learning process and the model’s behavior. In the context of inference, these hyperparameters can be organized into three categories: sampling, penalization, and generation control. Sampling hyperparameters determine how the next token is selected, including temperature, top-k, and top-p. Penalization hyperparameters adjust probabilities to avoid excessive repetition, while control hyperparameters define structural limits of the output, such as the maximum number of tokens and stop sequences [3].

Temperature regulates the level of randomness in text generation. Low values tend to produce more deterministic and precise outputs [4], while higher values increase diversity and the risk of incoherence [5]. Studies indicate that temperatures close to 0.0 are suitable for reasoning and translation, temperatures above 1.0 favor creativity, and values higher than 1.6 may lead to the so-called temperature paradox [4], [6].

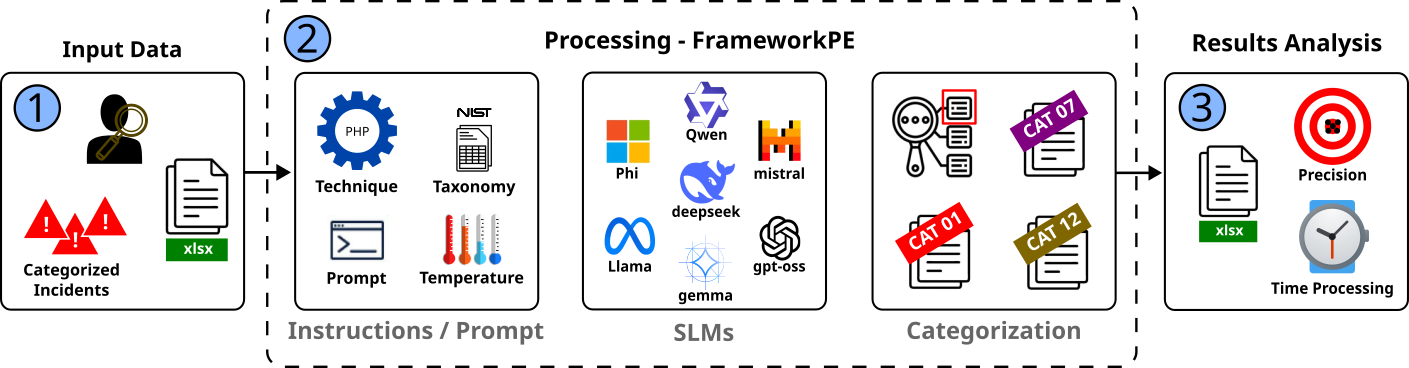

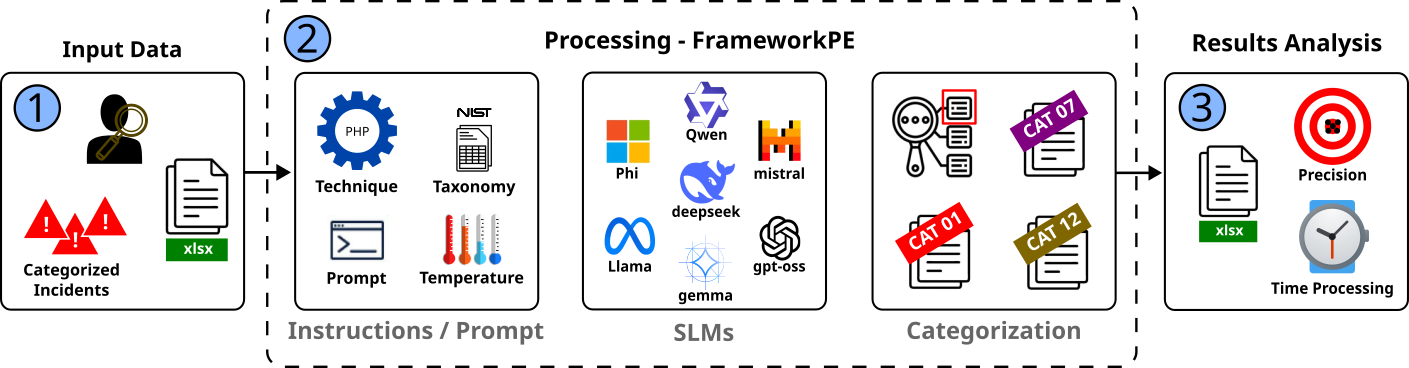

The experiments were structured as illustrated in Figure 1, following a three-stage pipeline similar to that adopted in recent studies (e.g., [7], [8]): Input Data, Processing, and Results Analysis. The objective was to evaluate the automated categorization of security incidents considering variations in temperature, processing time, and precision. For the experiments, two distinct computational architectures were used: (i) an AMD Ryzen 7 4800H with 32 GB of RAM and an NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1650 GPU (4 GB), and (ii) an Intel Core i7-12700 with 64 GB of RAM and an NVIDIA RTX A4000 GPU (16 GB).

Regarding the Input Data used to evaluate the performance of SLMs in classifying security incidents, we employed the dataset of real CSIRT incidents created and described by [7]. The original dataset contains 194 anonymized records, from which we selected a balanced subset composed of six distinct categories, each containing four incidents. The number of incidents per class was determined by the minority classes. The entire original dataset had previously been classified by two cybersecurity specialists, who independently analyzed the incidents, establishing a ground truth for comparison with the automated results. In the Processing stage, we used FrameworkPE2 , which implements several prompt engineering techniques. The user can select the desired technique, and for our experiments, we adopted PHP, which achieved the best results among the techniques recently evaluated for security incident classification [8]. PHP is complemented by the use of a baseline taxonomy (NIST), textual rules for output standardization, parametrization of inference temperature, and the selection of different SLMs.

We included models ranging from 1 to 20 billion parameters made available by the Ollama provider (version 0.12.3), totaling 21 language models from seven different vendors. Each execution produces a collection of categorized incidents, which is subsequently used in the evaluation stage. The final stage, Results Analysis, consisted of measuring precision (comparison between inference and the ground truth) and processing time obtained by each model, considering the two hardware architectures used in the evaluation: Ryzen7/GTX 1650 and i7/RTX A4000.

Table I presents the execution times of the 21 evaluated language models under four temperature configurations (T0, T0.4, T0.7, and T1). The values are displayed in the H:MM:SS format, including totals per model and per temperature configuration.

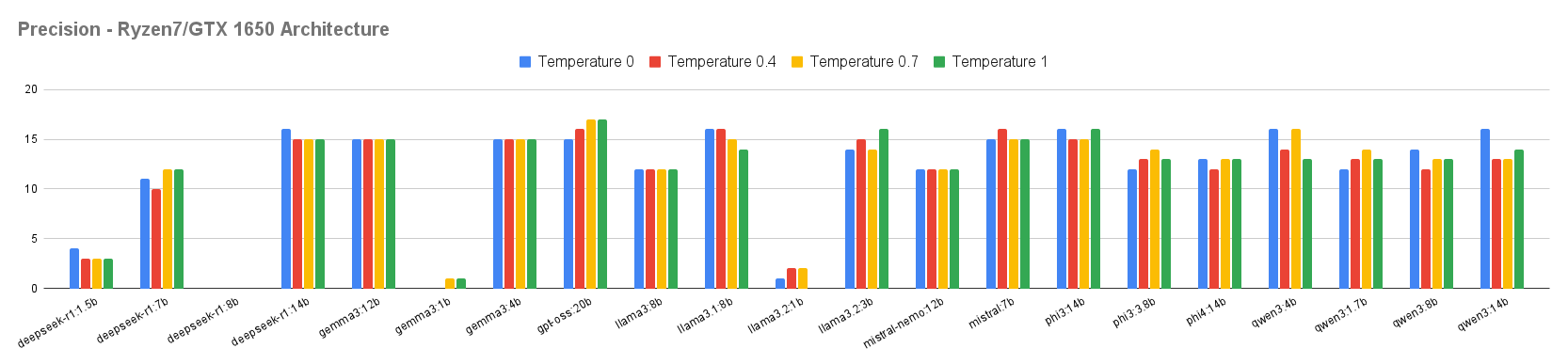

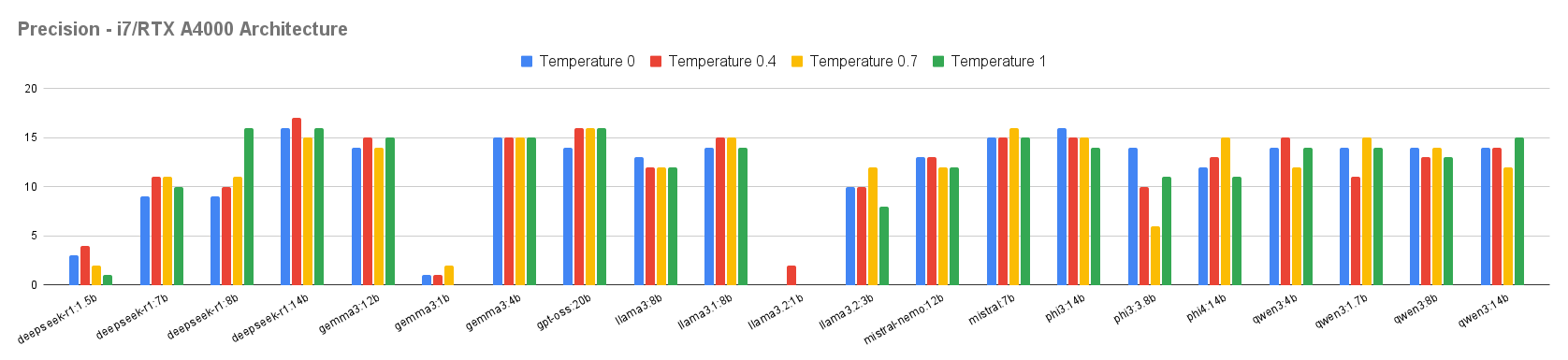

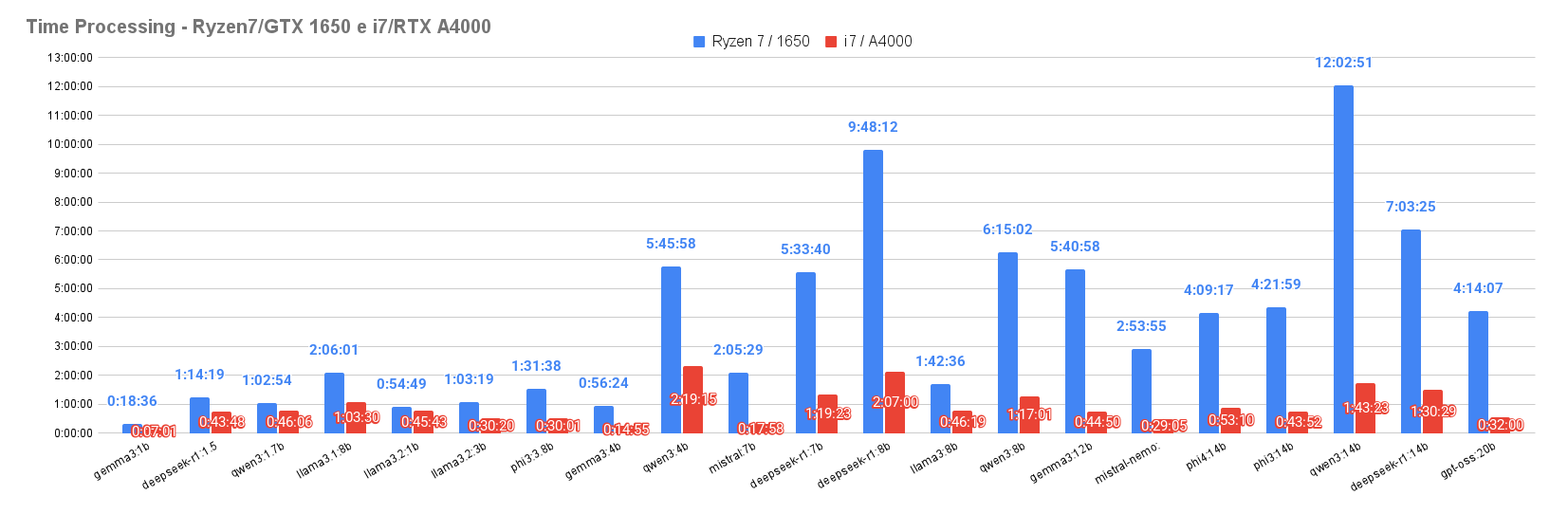

Figure 2 shows that the Ryzen7/GTX 1650 architecture exhibited significantly higher execution times, whereas the i7/RTX A4000 architecture achieved substantially faster performance. This difference reflects the greater efficiency of CPU and GPU resource management in the second architecture, highlighting the direct impact of the execution environment on model performance.

As observed, the variation in the execution time between the different temperatures (T0, T0.4, T0.7, and T1) is relatively small, suggesting that the temperature hyperparameter primarily influences the diversity and textual coherence of the responses rather than inference time. However, smaller models such as gemma3:1b, deepseek-r1:1.5b, and llama3:1.8b exhibit execution times far below those of larger models such as gpt-oss:20b and deepseek-r1:14b. These results reinforce the notion that the number of parameters is one of the decisive factors for computational cost.

In the i7/RTX A4000 architecture, the greater dispersion in execution times can be explained by the way Ol

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.