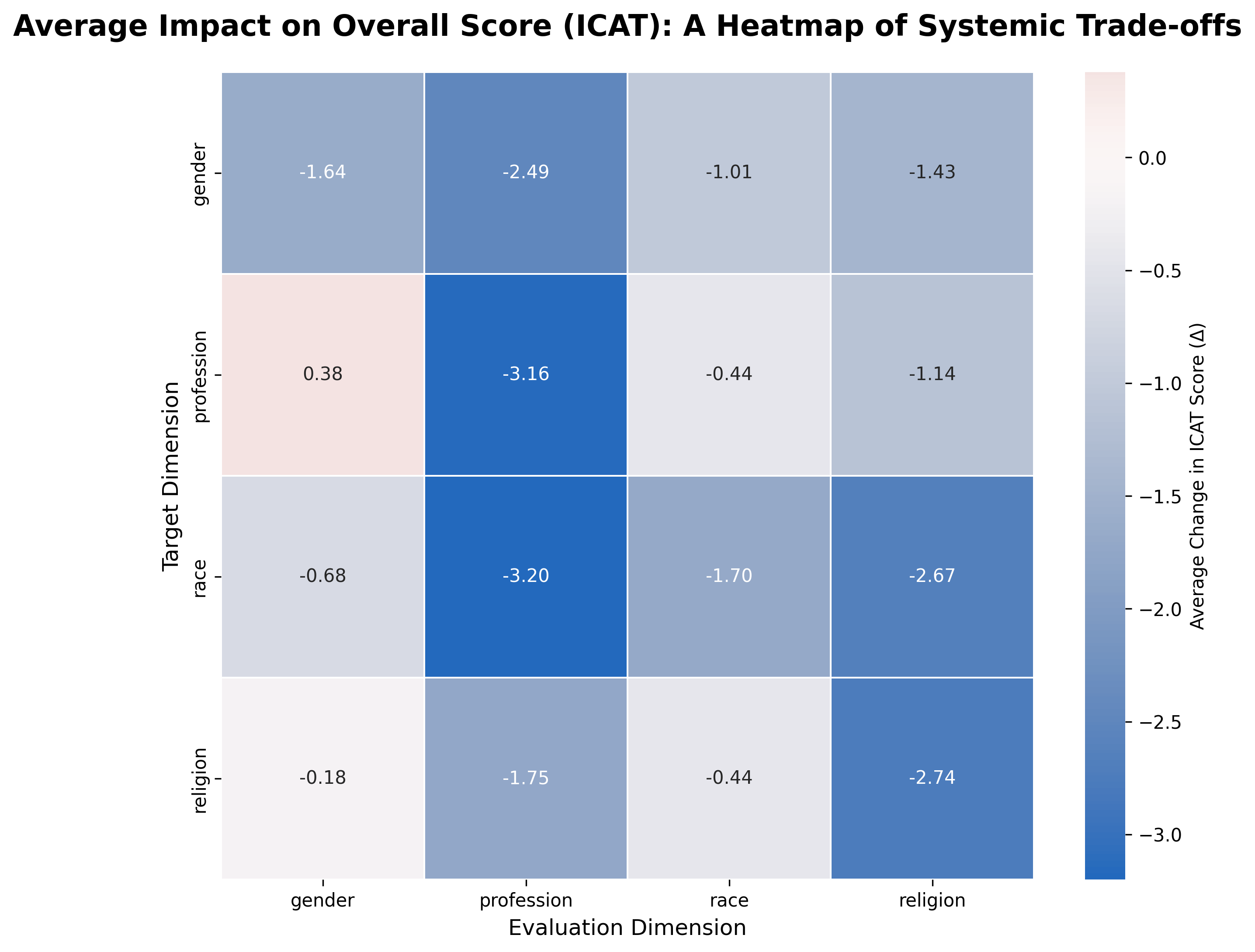

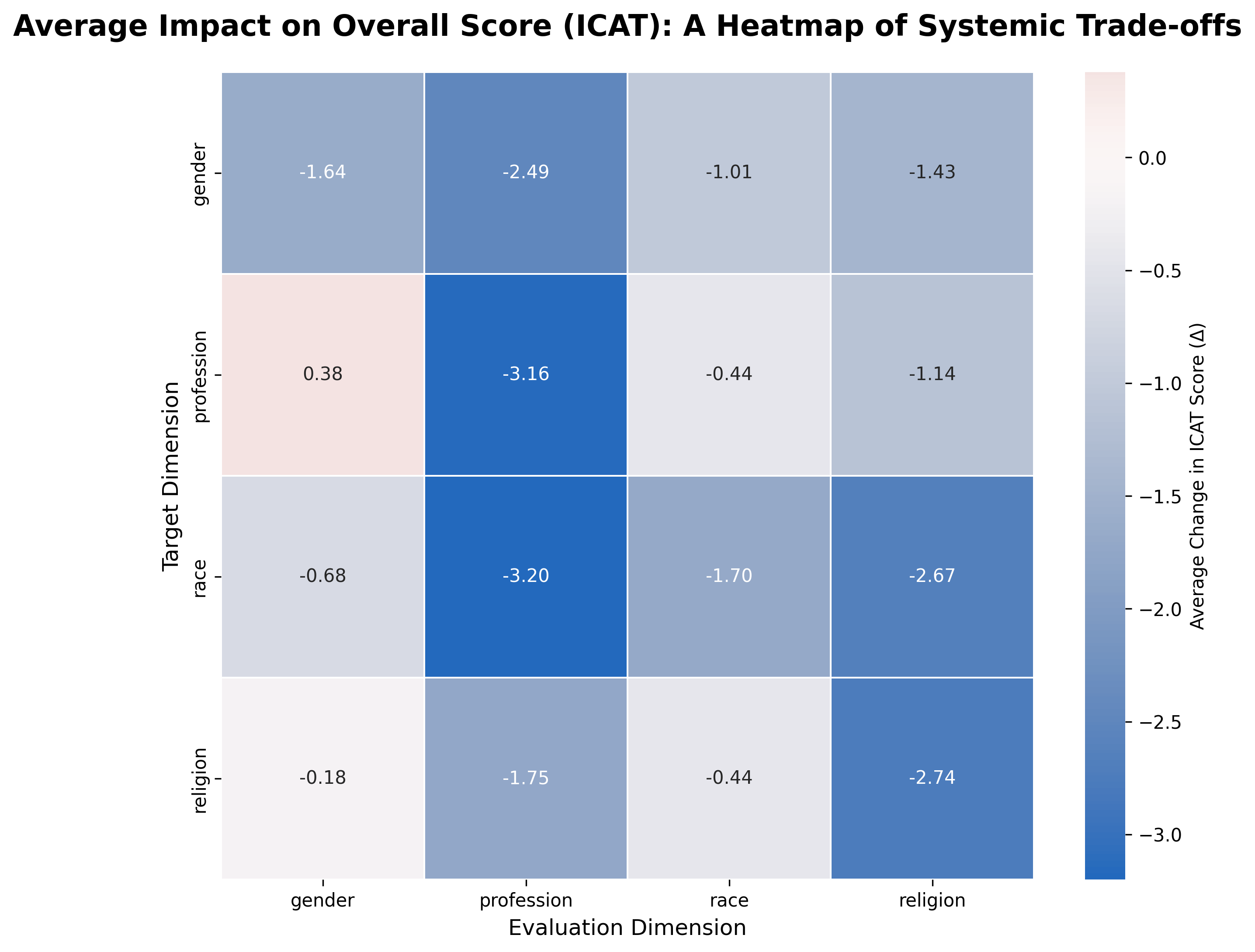

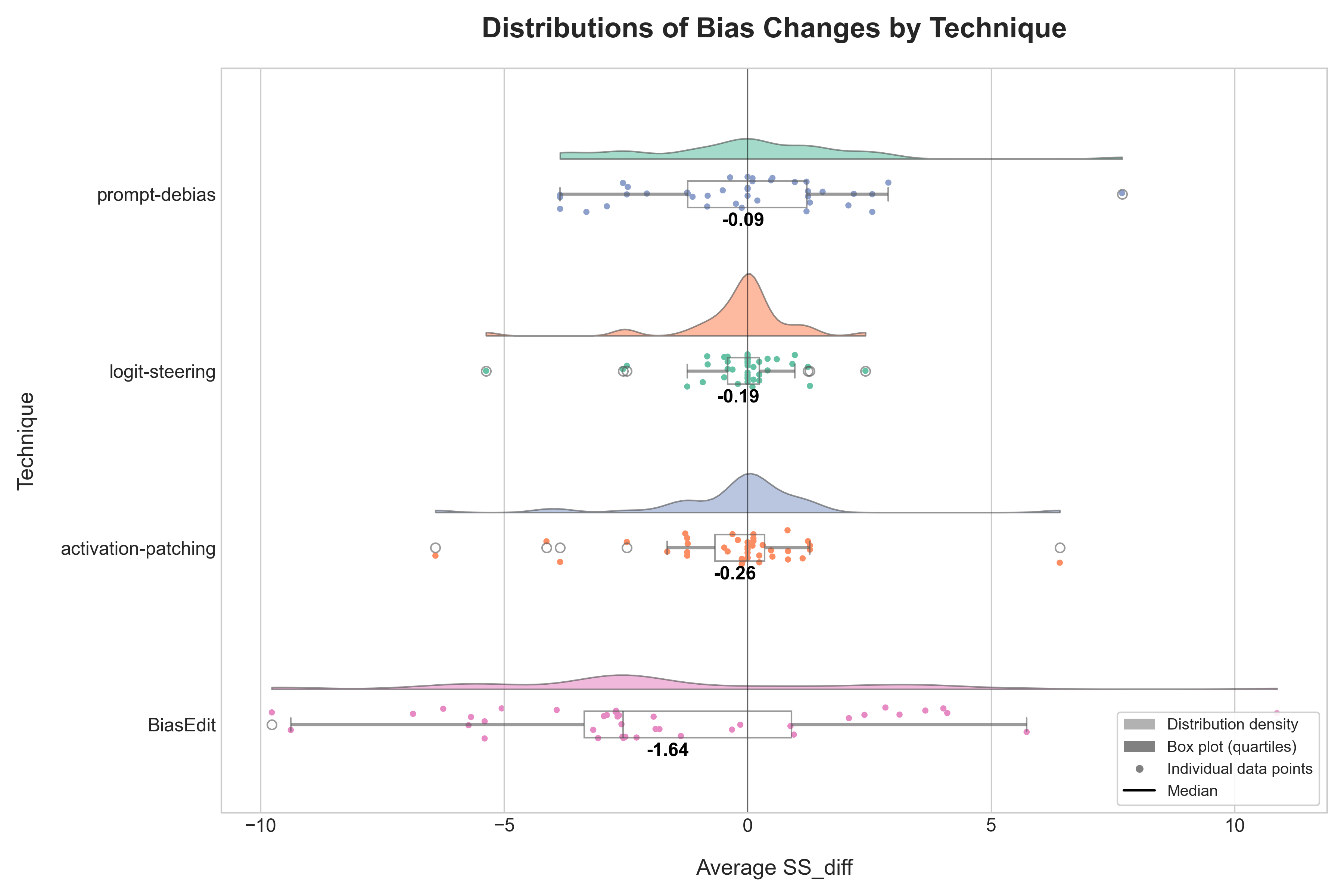

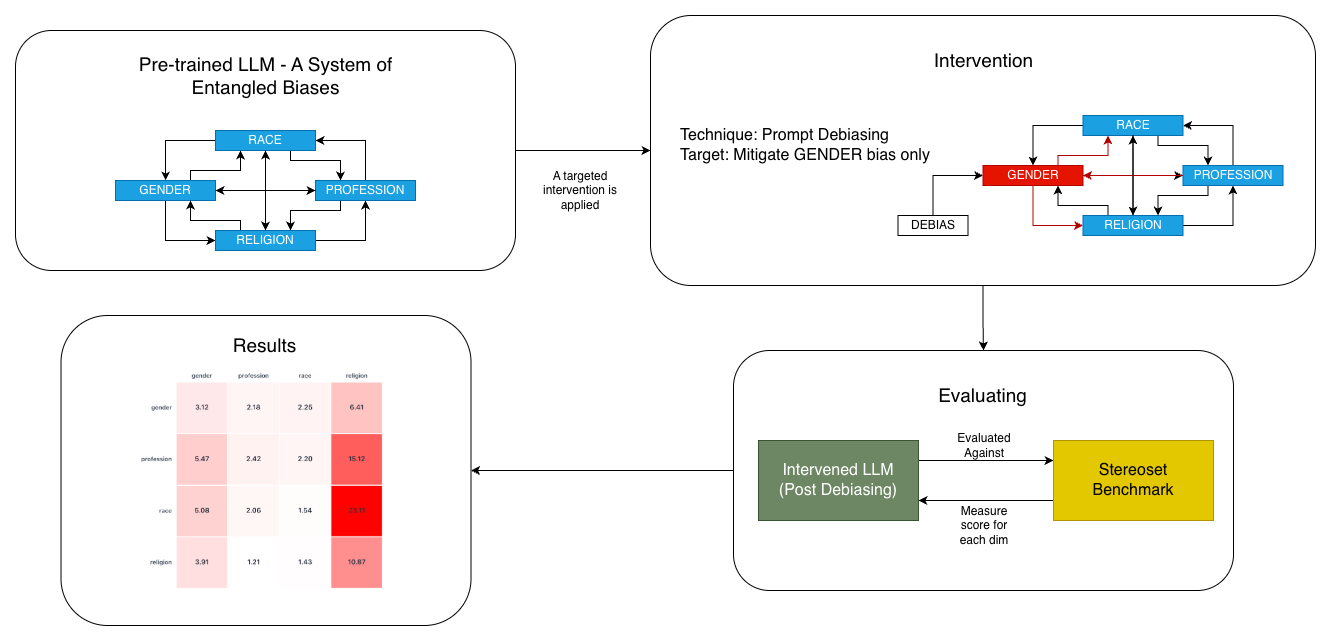

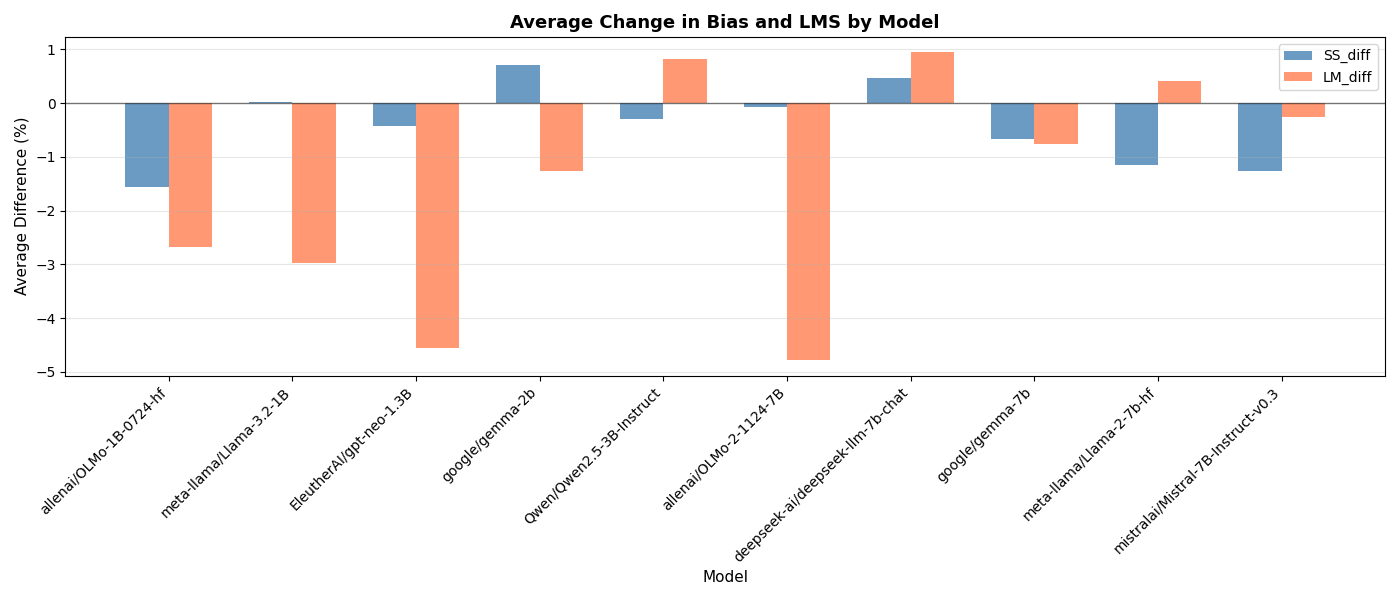

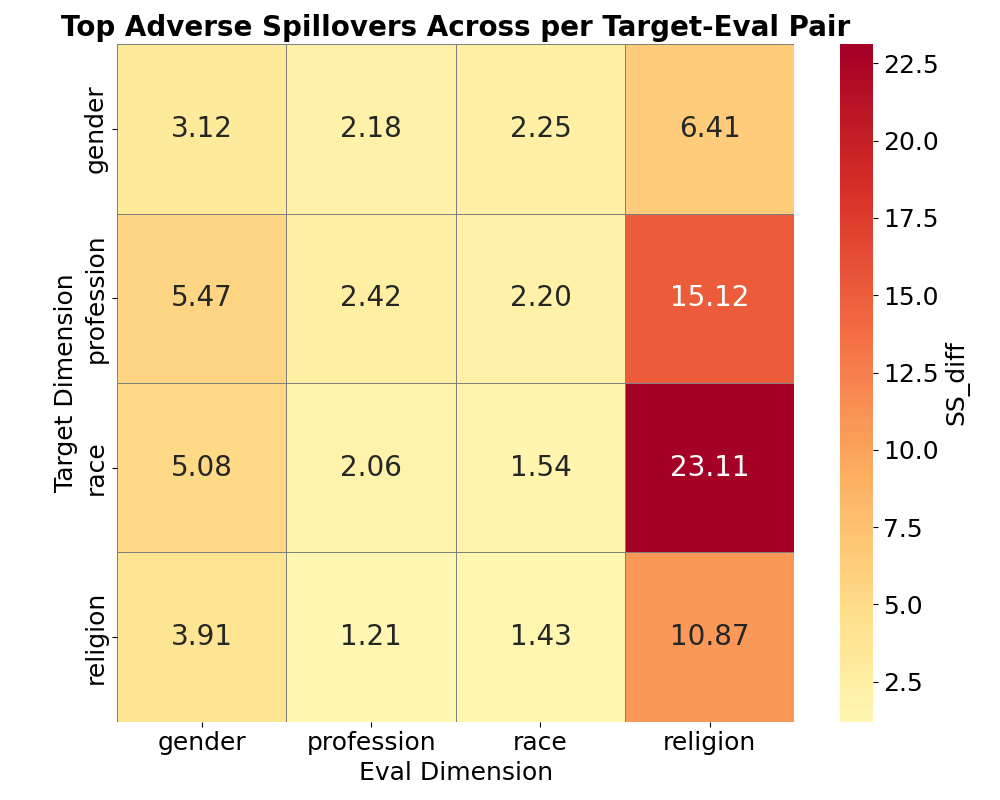

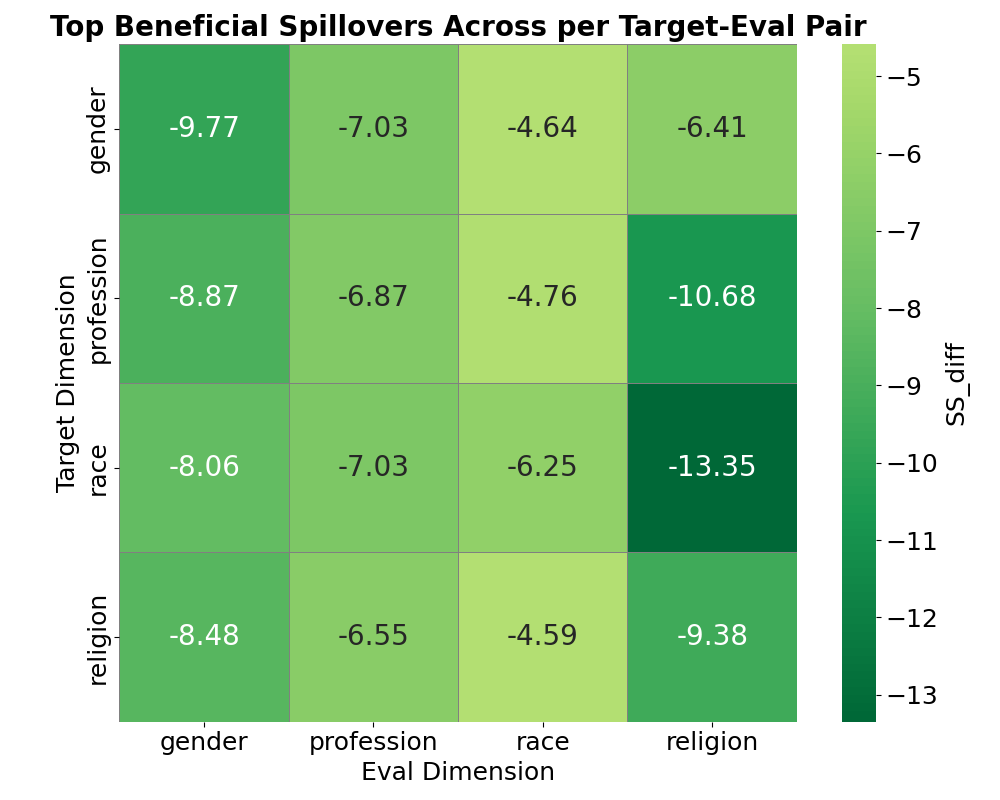

Large Language Models (LLMs) inherit societal biases from their training data, potentially leading to harmful or unfair outputs. While various techniques aim to mitigate these biases, their effects are often evaluated only along the dimension of the bias being targeted. This work investigates the cross-category consequences of targeted bias mitigation. We study four bias mitigation techniques applied across ten models from seven model families, and we explore racial, religious, profession- and gender-related biases. We measure the impact of debiasing on model coherence and stereotypical preference using the StereoSet benchmark. Our results consistently show that while targeted mitigation can sometimes reduce bias in the intended dimension, it frequently leads to unintended and often negative consequences in others, such as increasing model bias and decreasing general coherence. These findings underscore the critical need for robust, multi-dimensional evaluation tools when examining and developing bias mitigation strategies to avoid inadvertently shifting or worsening bias along untargeted axes.

Large Language Models (LLMs) have become known as a widespread and revolutionary technology, embedded in many different applications that influence how we access information, create content and interact with the digital world. However, their increasing adoption is accompanied by a fundamental challenge: LLMs trained on large corpora of human-generated content inherit and frequently exacerbate deeply ingrained societal prejudices regarding race, gender, religion and other sensitive categories [43,13]. The risk of these models reinforcing harmful stereotypes is a critical barrier to their safe and fair adoption, making the development of effective bias mitigation techniques a central focus of AI research [3,42,10].

Numerous mitigation strategies have been proposed, ranging from data debiasing and constrained decoding to fine-tuning and parameter editing [5,6,23,25]. However, the evaluation of these techniques often focuses narrowly on the specific bias dimension being targeted for reduction. Less understood are the potential side effects or cross-category impacts: for example, how does attempting to mitigate gender bias affect religious bias, or how does targeting race bias influence profession-related stereotypes?

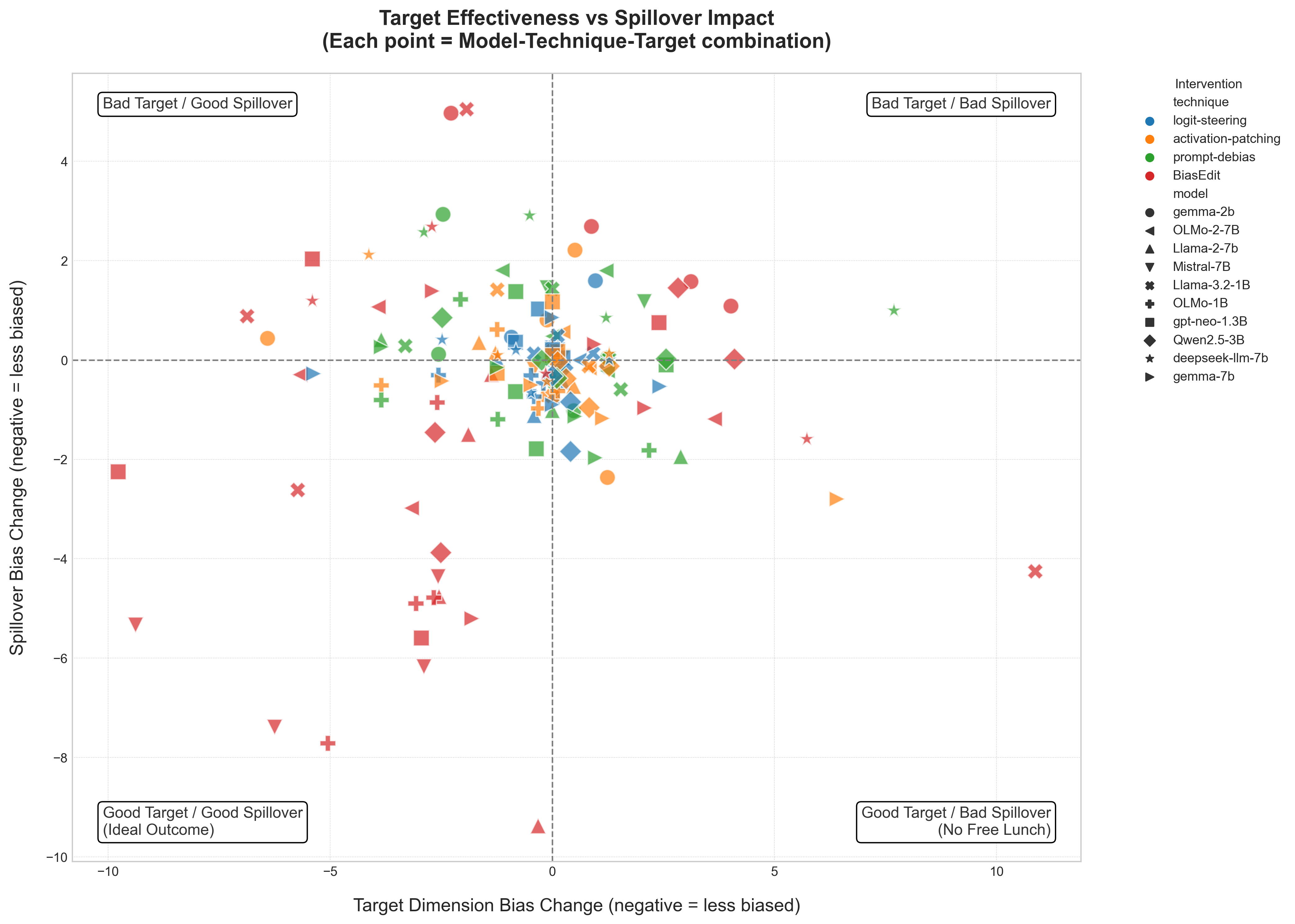

This paper addresses this gap by systematically investigating the cross-category effects of several common mitigation strategies. Our research question is: How does the mitigation of bias along a single axis (e.g., gender) affect the model’s performance along several axes (gender, profession, religion, and race)? Our work is motivated by this fundamental question, operating under the hypothesis that there is No Free Lunch in language model bias mitigation: We hypothesize that, due to the entangled nature of conceptual representation with LLMs, targeted interventions on singular bias dimensions will inevitably cause unintended 2 Related Work

Efforts to improve fairness in LLMs often reveal just how intertwined linguistic structures and representations are within models. While the study of bias and fairness in machine learning is a well-established field, the notion of interconnectedness extends beyond the scope of LLMs and bias research specifically; adjustments to certain specific representational components in complex technological systems inevitably lead to unforeseen trade-offs [22].

This challenge is fundamentally related to the “No Free Lunch” (NFL) theorem for optimization originally proposed by Wolpert and Macready in 1997 [44]. The NFL theory states that, for a given search or optimization algorithm, any gains in performance on one class of problems are necessarily offset by losses in performance on another class of problems. When applied to machine learning, the theory suggests that no single, universally superior algorithm or intervention exists for any type of problem, as improvements in one aspect of a system often come at the expense of another. We furthered this idea in the context of AI systems by positing the problem of “Butterfly Effect” in AI bias: small, targeted interventions can trigger cascading and unpredictable consequences in the broader system’s behavior [11]. Though their original contexts are much wider in scope, both the Butterfly Effect and the NFL theory work in concert to offer a theoretical lens for the analysis of intervention trade-offs in bias mitigation.

Various recent surveys [27,36,12] offer extensive overviews of the different sources of bias, starting from historical representation in training data to algorithmic processing and the different mathematical definitions of fairness.

To quantify these biases, a variety of benchmarks have been developed. For example, datasets like CrowS-Pairs [31] and WinoBias [48] measure bias through paired sentences that differ only by a demographic term; the BOLD dataset [9] evaluates bias in open-ended text generation across a vast number of prompts. Bias evaluation has also been extended into other realms such as question answering [35] and Vision Language Models [40].

Our work adopts the StereoSet benchmark [30], which is uniquely suited to our research goals. Unlike binary choice datasets, StereoSet presents example contexts paired with triplets of sentences (stereotype, anti-stereotype, unrelated) which allows for the disentanglement of a model’s linguistic coherence from its stereotypical preference. This is critical as Wang et al. [41] find that there are significant trade-offs between fairness and accuracy in contexts like multitask learning. Furthermore, it has been shown that catastrophic forgetting [21] is a significant challenge for neural networks and LLMs in both learning and unlearning tasks [32,33,18]; thus, measuring how debiasing affects model coherence is of essence. Additionally, StereoSet’s multidimensional nature, covering race, gender, religion and profession, is also a prerequisite for our investigation into the cross-dimensional effects of bias mitigation.

A significant body of work has focused

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.