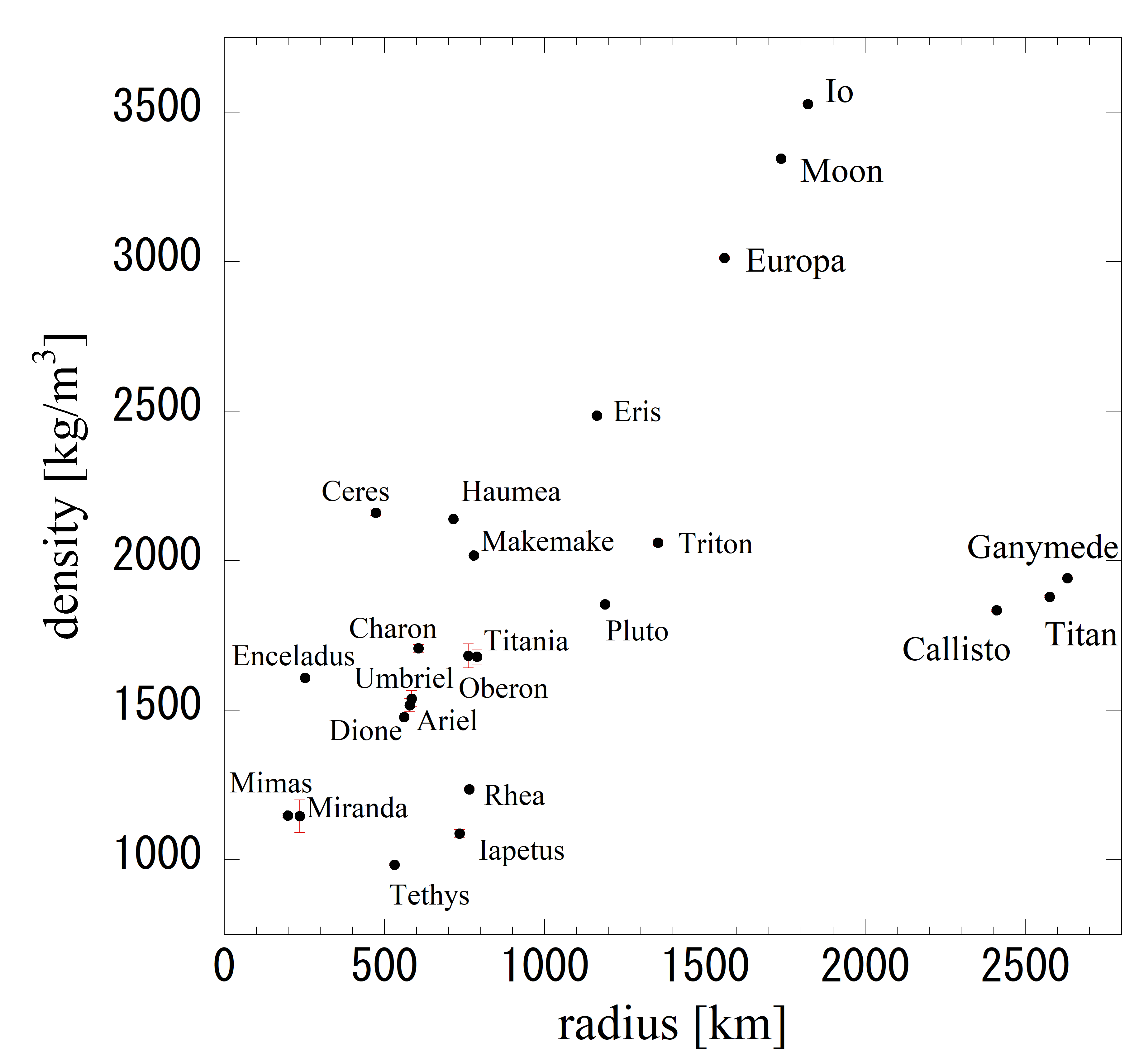

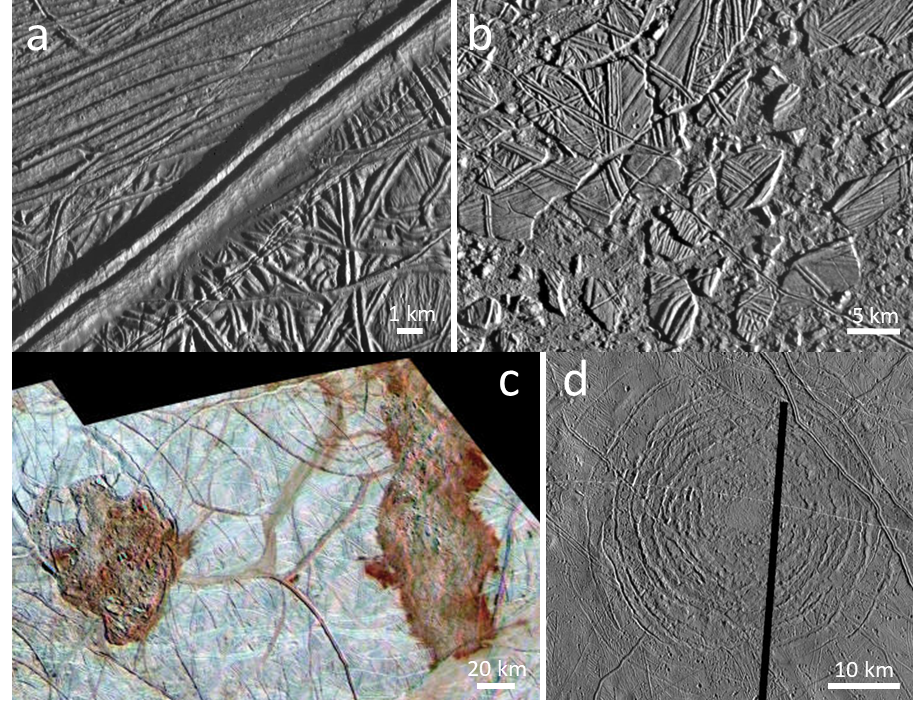

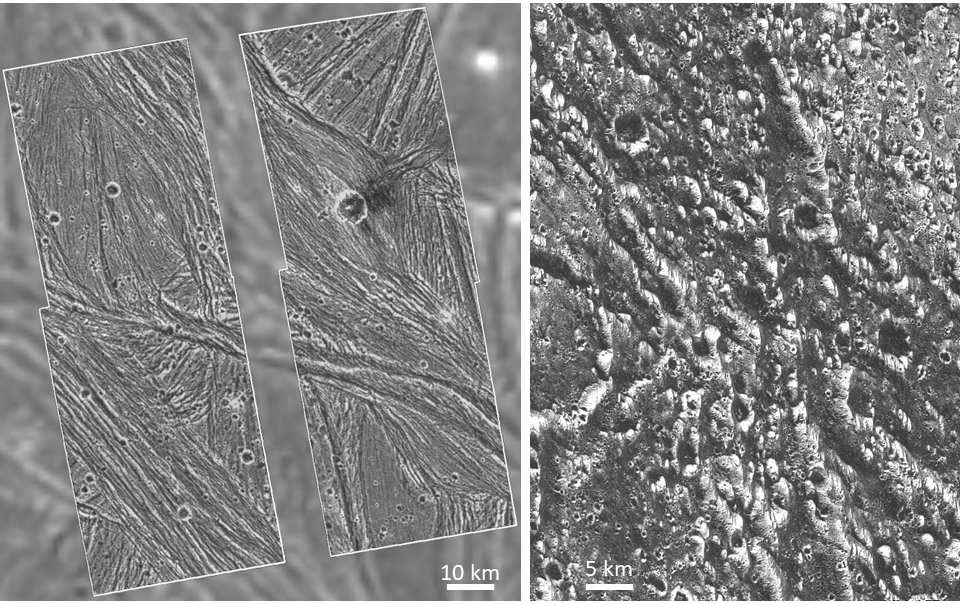

In the outer solar system beyond Jupiter, water ice is a dominant component of planetary bodies, and most solid objects in this region are classified as icy bodies. Icy bodies display a remarkable diversity of geological, geophysical, and atmospheric processes, which differ fundamentally from those of the rocky terrestrial planets. Evidence from past and ongoing spacecraft missions has revealed subsurface oceans, cryovolcanic activity, and tenuous but persistent atmospheres, showing that icy bodies are active and evolving worlds. At the same time, major questions remain unresolved, including the chemical properties of icy materials, the geological histories of their surfaces, and the coupling between internal evolution and orbital dynamics. Current knowledge of the surfaces, interiors, and atmospheres of the principal icy bodies is built on spacecraft measurements, telescopic observations, laboratory experiments, and theoretical modeling. Recent contributions from Juno, James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), and stellar occultation studies have added valuable constraints on atmospheric composition, interior structure, and surface activity. Looking ahead, missions such as JUpiter ICy moons Explorer (JUICE), Europa Clipper, Dragonfly, and the Uranus Orbiter and Probe are expected to deliver substantial progress in the study of icy bodies. Their findings, combined with continued Earth-and space-based observations and laboratory studies, will be critical for assessing the potential habitability of these environments and for placing them within a broader framework of planetary system formation and evolution.

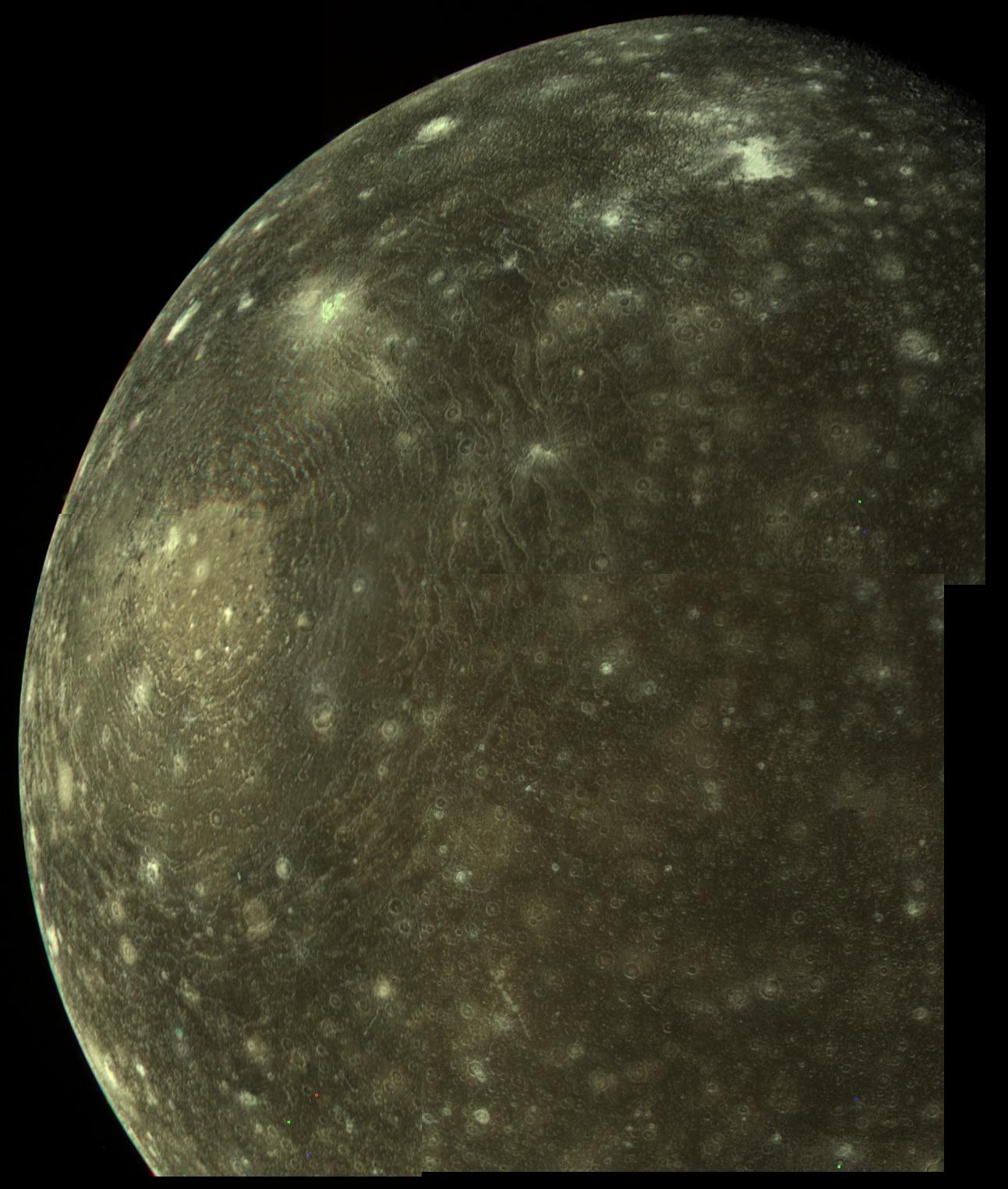

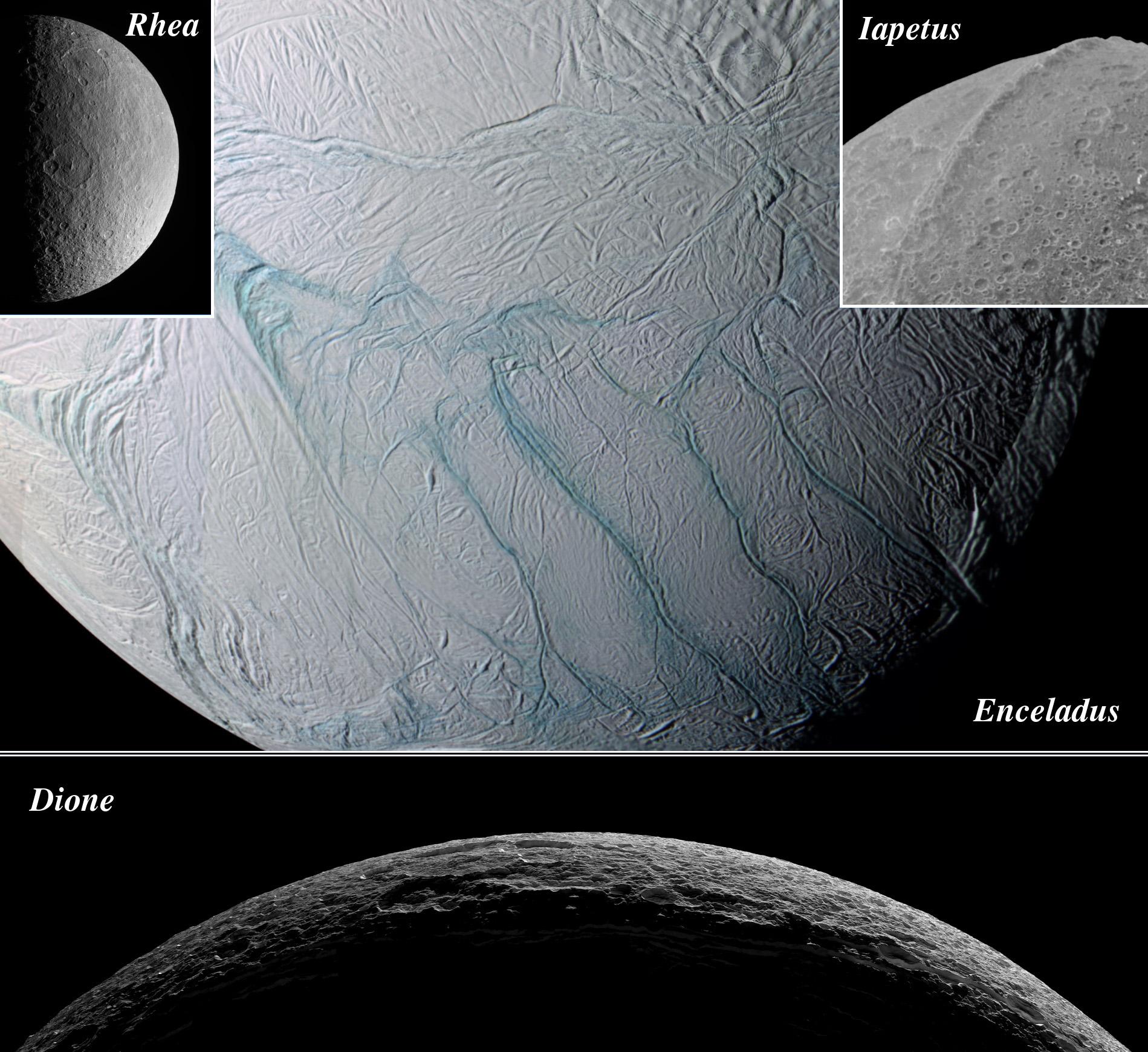

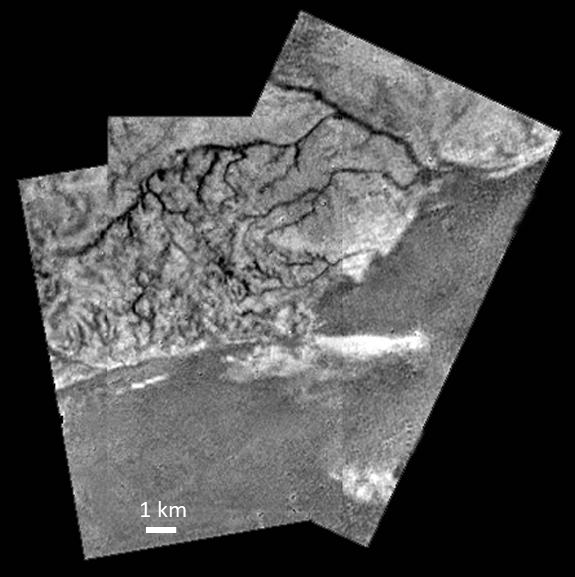

Ice typically refers to solid H 2 O and is widely identified on Earth. In planetary science, ice refers to any solid volatile material, including not only water ice but also CO 2 ice, N 2 ice, hydrocarbon ice, and others. Water ice is the most common solid volatile material and has been confirmed to exist on various planetary bodies throughout the Solar System, even at the polar craters of Mercury. These various types of ice significantly influence the geological and atmospheric characteristics of solar system bodies. From NASA's Planetary Photojournal (https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/), Earth's Moon (PIA00302), Europa (PIA00502), Ganymede (PIA00716), Callisto (PIA03456), Mimas (PIA06258), Enceladus (PIA06254), Tethys (PIA07738), Dione (PIA08256), Rhea (PIA08256), Titan (PIA08256), Hyperion (PIA07740), Iapetus (PIA08384), Phoebe (PIA06064), Miranda (PIA18185), Ariel (PIA01534), Umbriel (PIA00040), Titania (PIA01979), Oberon (PIA00034), Triton (PIA00317), Pluto (PIA19952). Brown and Butler (2023).

[8] Sicardy et al. (2011).

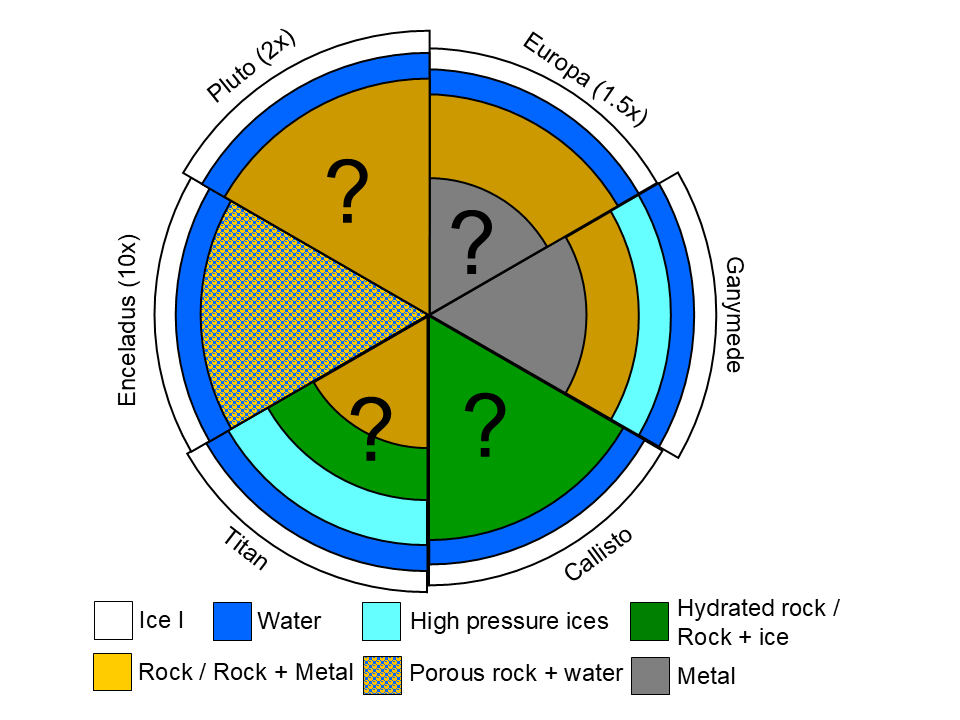

elastic deformation of the Earth (Love, 1892). These parameters characterize different aspects of planetary response to tidal potential: k 2 measures potential perturbation in the gravitational field, h 2 represents vertical surface displacement, and l 2 describes horizontal displacement. Tidal responses depend on the body’s internal structure and composition; if it contains highly deformable materials, such as a global subsurface ocean, that respond strongly to tidal potential, the magnitude of the deformation can be substantially greater. For Titan, k 2 has been derived from gravitational measurement by the Cassini spacecraft, leading to the prediction of a subsurface ocean (Durante et al., 2019;Goossens et al., 2024).

Many moons also exhibit synchronous rotation, in which orbital rotation is gravitationally locked to the central planet so that the same hemisphere always faces the planet. Such a body has leading and trailing hemispheres relative to the orbital direction. Synchronous rotation leads to triaxial deformation under the combined effect of self-rotation and tidal forces, and precise measurements of a moon’s shape can provide further constraints on its interior. If the orbital periods of two moons can be expressed as a ratio of integers, they are in orbital resonance. Examples include the 1:2:4 resonance of Ganymede, Europa, and Io, and the 1:2 resonance of Dione and Enceladus. Orbital eccentricity of moons in resonance can be strongly enhanced, and the resulting frictional heat from periodic deformation can become a significant internal energy source. Orbital eccentricity also induces oscillations in a moon’s spin rate about its equilibrium mean value, producing a forced libration primarily in longitude. Measurements of libration amplitudes can provide evidence for subsurface oceans, as suggested for Enceladus (Thomas et al., 2016).

Electromagnetic interactions between a planet and its moon can provide crucial information about the presence of a global salty ocean within the moon. If the planet’s magnetospheric equator is tilted relative to the moon’s orbital plane, the moon passes through both the northern and southern hemispheres of the planet’s magnetosphere during its orbit. These periodic shifts in the magnetic field generate eddy currents in any conductive layer within the moon, such as a subsurface salty ocean, which in turn induces a secondary magnetic field. At Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto, Galileo spacecraft observed fluctuations in the surrounding magnetic environment, which strongly suggest the presence of subsurface salty oceans (Kivelson et al., 2007). However, if the planet’s magnetospheric equator is aligned with the moon’s orbital plane, as is the case in the Saturnian system, the magnetic field at the moon remains constant over time, preventing any significant inductive response.

Impact craters on surfaces provide crucial information for understanding the geological history of these bodies. Generally, crater size-frequency distributions (SFDs) on bodies in the outer Solar System differ significantly from those observed in the inner Solar System such as on the Moon (Strom et al., 2015). In the outer Solar System. the main sources of impactors are considered to be ecliptic comets and long-period comets (Levison et al., 2000;Zahnle et al., 2003), which contrasts with the small asteroids from the main asteroid belt that primarily strike terrestrial bodies in the inner Solar System (Strom et al., 2015). As a result, impact crater production functions derived from the Moon and Mars are inconsistent with those on the outer Solar System. It should be noted that surface ages estimated from crater chronologies for outer Solar System bodies include large uncertainties in impact rates and crater formation mechanisms.

This chapter provides an overview of current knowledge of icy bodies derived from observations, in-situ explorations, and theoretical modeling.

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.