This paper presents an application of the Infinite Unit Axiom, introduced by Yaroslav Sergeyev, (see [11] - [14]) to the development of one-dimensional cellular automata. This application allows the establishment of a new and more precise metric on the space of definition for one-dimensional cellular automata, whereby accuracy of computations is increased. Using this new metric, open disks are defined and the number of points in each disk is computed. The forward dynamics of a cellular automaton map are also studied via defined equivalence classes. Using the Infinite Unit Axiom, the number of configurations that stay close to a given configuration under the shift automaton map can now be computed.

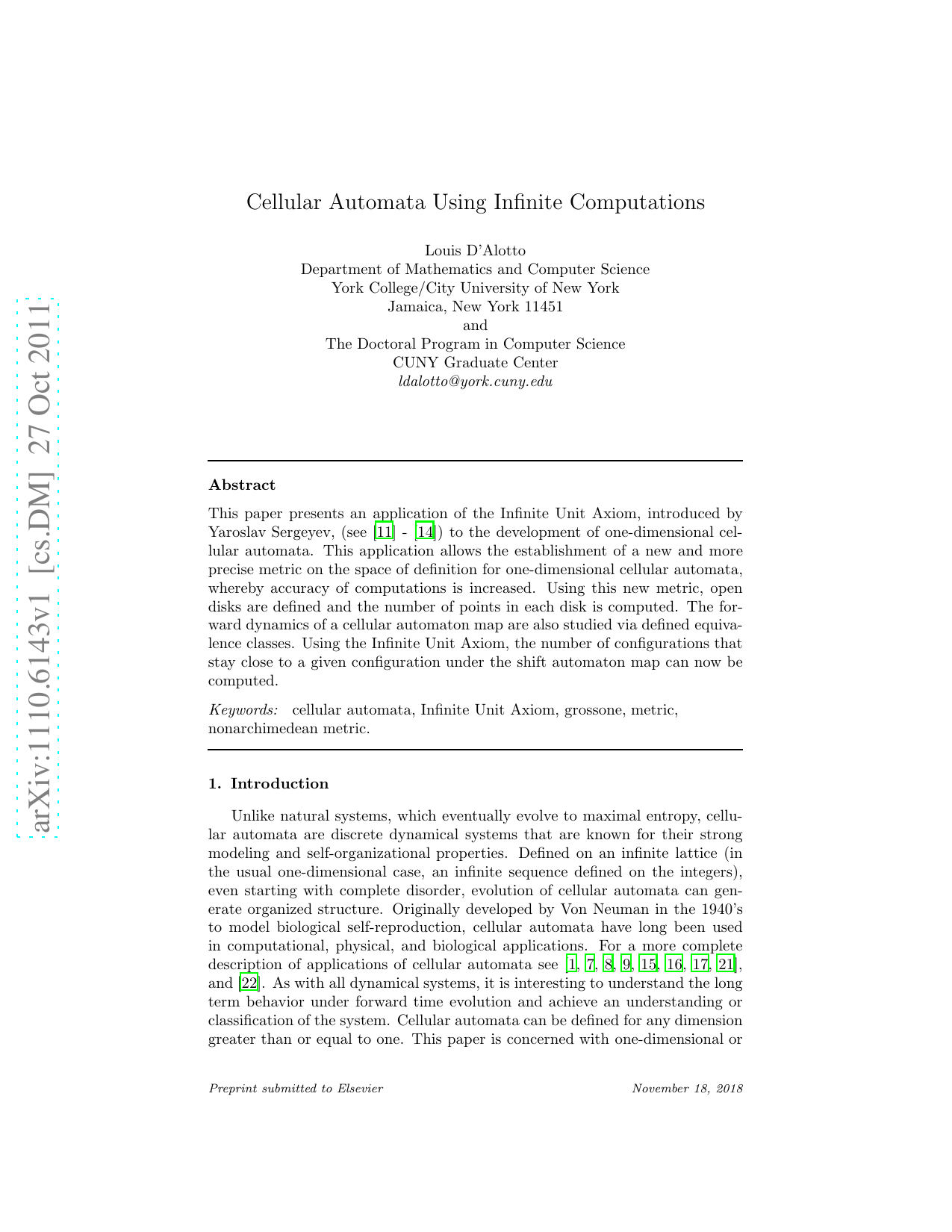

Unlike natural systems, which eventually evolve to maximal entropy, cellular automata are discrete dynamical systems that are known for their strong modeling and self-organizational properties. Defined on an infinite lattice (in the usual one-dimensional case, an infinite sequence defined on the integers), even starting with complete disorder, evolution of cellular automata can generate organized structure. Originally developed by Von Neuman in the 1940's to model biological self-reproduction, cellular automata have long been used in computational, physical, and biological applications. For a more complete description of applications of cellular automata see [1,7,8,9,15,16,17,21], and [22]. As with all dynamical systems, it is interesting to understand the long term behavior under forward time evolution and achieve an understanding or classification of the system. Cellular automata can be defined for any dimension greater than or equal to one. This paper is concerned with one-dimensional or linear cellular automata defined on the integers (when no confusion arises, we will refer to one-dimensional cellular automata as simply cellular automata). See figure 1 for an example of a one-dimensional cellular automaton. This is Wolfram binary rule 20 with range equal to 2, see [18] and [19]. Starting with a random initial configuration, the cellular automaton evolves (under repeated applications) downward. In this example, it's interesting to note the two persisting structures that emerge. The structure on the left evolves straight down, while the structure on the right evolves down on an angle and can eventually "crash" into other persisting structures.

The concept of classifying cellular automata was initiated by Stephen Wolfram, see [19]. In [19], one-dimensional cellular automata are partitioned into four classes depending on their dynamical behavior. Figure 1 (rule 20) is an example of a Wolfram class 4 cellular automaton. A later and more rigorous classification scheme, see [5], was developed by Robert Gilman. Here a probabilistic/measure theoretic classification was developed based on the probability of choosing a sequence that will stay arbitrarily close to a given initial sequence under forward evolution (iteration). Gilman uses a metric that considers the central window where two sequences (configurations) agree and continue to agree upon forward iterations of a cellular automaton map. However, in the development, this metric is limited because it doesn’t take into account configurations that agree on an infinite interval to the right (or respectively to the left). Indeed, the metric considers the absolute value of the first integral place where configurations disagree and uses that as their distance apart, see [4] and [5]. For example, if configurations agree on the right hand side out to infinity but disagree in some finite position on the left, their distance apart is determined by where they disagree on the left. In this paper, the definition of cellular automata and the metric involved are extended to include configurations that do not necessarily agree on a finite central window symmetric around 0, and also which can agree on not necessarily symmetric infinite intervals.

The classical concept of infinity has presented limitations in computations. Indeed, metrics used on infinite sequences, and hence cellular automata, either do not allow us to observe minute differences or can lead to calculations beyond finite computations. Analogous to the Hamming distance for finite sequences, the following metric is used to compute distances between infinite sequences.

Here the differences in the respective sequence values are computed and divided by 2 |i| to ensure convergence. However, this procedure can lead to a calculation beyond finite computation and to possible inaccuracies. For instance, using the binary alphabet S={0,1}, suppose two sequences agree completely on the left of and at the 0 th place, and disagree elsewhere. That is, they disagree on the right of 0 or for integral values i > 0. Applying the traditional well known formula to (1) yields

and taking limits as k approaches infinity, results in a value of 1. By using the Infinite Unit Axiom, see [11] - [14], and |N| = ① (the symbol ① is called grossone by Sergeyev and represents the number of elements in the set of natural numbers), the computational limitations caused by sequences that agree out to one-sided infinity or that are subject to infinite computations are overcome. As shown for infinite k, that is for

and note that 1 2 ① is infinitesimal (see [11]). Hence (3) produces a more precise representation of the infinite sum computation. Before defining cellular automata with the infinite metric we need a few preliminaries. The set of integers is denoted by Z; N is the set of natural numbers and let N 0 = N ∪ {0}. Given a finite alphabet S with two or more symbols, i.e. |S| ≥ 2, consider the space of all functions from the integers to the

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.