The Shadow of the Moon in IceCube

📝 Original Info

- Title: The Shadow of the Moon in IceCube

- ArXiv ID: 1111.2969

- Date: 2019-08-13

- Authors: L. Gladstone (for the IceCube Collaboration)

📝 Abstract

IceCube is the world's largest neutrino telescope, recently completed at the South Pole. As a proof of pointing accuracy, we look for the image of the Moon as a deficit in down-going cosmic ray muons, using techniques similar to those used in IceCube's astronomical point-source searches.💡 Deep Analysis

📄 Full Content

arXiv:1111.2969v1 [astro-ph.HE] 12 Nov 2011

The Shadow of the Moon in IceCube

L. Gladstone, for the IceCube Collaboration a

University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1150 University Avenue, Madison, WI 53706, USA

IceCube is the world’s largest neutrino telescope, recently completed at the South Pole. As

a proof of pointing accuracy, we look for the image of the Moon as a deficit in down-going

cosmic ray muons, using techniques similar to those used in IceCube’s astronomical point-

source searches.

1

Introduction

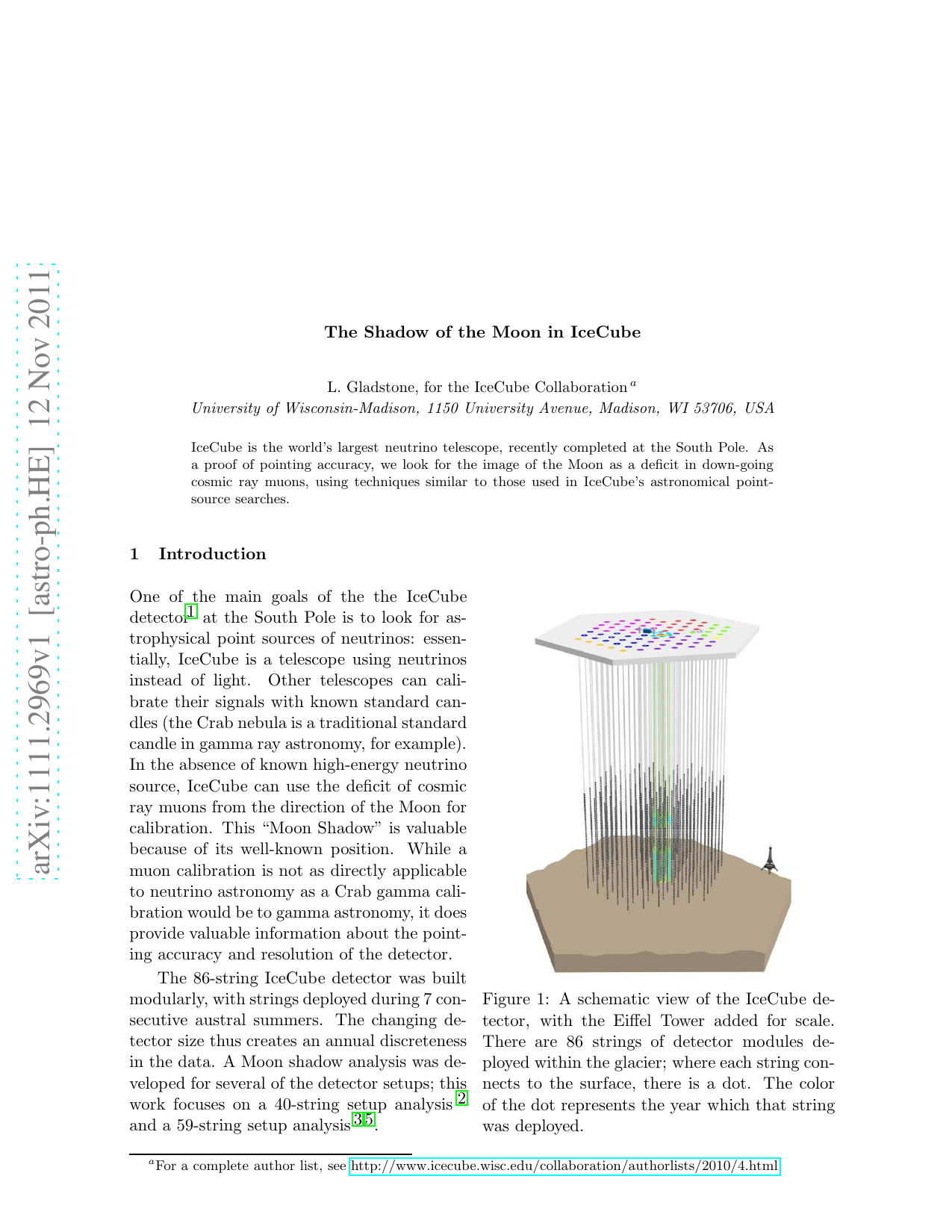

Figure 1: A schematic view of the IceCube de-

tector, with the Eiffel Tower added for scale.

There are 86 strings of detector modules de-

ployed within the glacier; where each string con-

nects to the surface, there is a dot. The color

of the dot represents the year which that string

was deployed.

One of the main goals of the the IceCube

detector1 at the South Pole is to look for as-

trophysical point sources of neutrinos: essen-

tially, IceCube is a telescope using neutrinos

instead of light.

Other telescopes can cali-

brate their signals with known standard can-

dles (the Crab nebula is a traditional standard

candle in gamma ray astronomy, for example).

In the absence of known high-energy neutrino

source, IceCube can use the deficit of cosmic

ray muons from the direction of the Moon for

calibration. This “Moon Shadow” is valuable

because of its well-known position. While a

muon calibration is not as directly applicable

to neutrino astronomy as a Crab gamma cali-

bration would be to gamma astronomy, it does

provide valuable information about the point-

ing accuracy and resolution of the detector.

The 86-string IceCube detector was built

modularly, with strings deployed during 7 con-

secutive austral summers. The changing de-

tector size thus creates an annual discreteness

in the data. A Moon shadow analysis was de-

veloped for several of the detector setups; this

work focuses on a 40-string setup analysis 2

and a 59-string setup analysis 3,5.

aFor a complete author list, see http://www.icecube.wisc.edu/collaboration/authorlists/2010/4.html

2

Data Sample

Because of bandwidth restrictions on the satellite transporting data from the South Pole to the

North for analysis, a subset of available IceCube data is used. For these analyses, the data were

collected in the following way: tracks were reconstructed quickly, and their direction of origin

was compared to the current position of the Moon. If an event came from a position within 40◦

in azimuth or 10◦in zenith, it was sent north. These data were collected only when the Moon

was 15◦or more above the horizon at the South Pole, which neatly splits the data into lunar

months. This sample was used for both a Moon measurement and an off-source background

estimate.

The estimated angular resolution of the reconstructions used here is of order 1◦, similar to

the 0.5◦-diameter Moon, so for this analysis the Moon was considered point-like.

3

Binned 40-string analysis

One analysis of the Moon Shadow was performed on the data set from the 40-string detector

setup. This dataset contained 13 lunar months. Cuts were applied to the data sample to optimize

the expected signal (balancing passing rate with the expected improvement to the point spread

function). Using simulation, the search bin size was optimized, and a band 1.25◦tall at constant

zenith with respect to the Moon was used. Figure 2 shows the number of events in this zenith

band, using the same optimized bin size of 1.25◦in azimuth as in zenith. Taking the mean of

all the bins excluding the central 4 as a comparison, and using simple statistical

√

N errors, we

see a deficit of 7.6σ in the central bin at the position of the Moon.

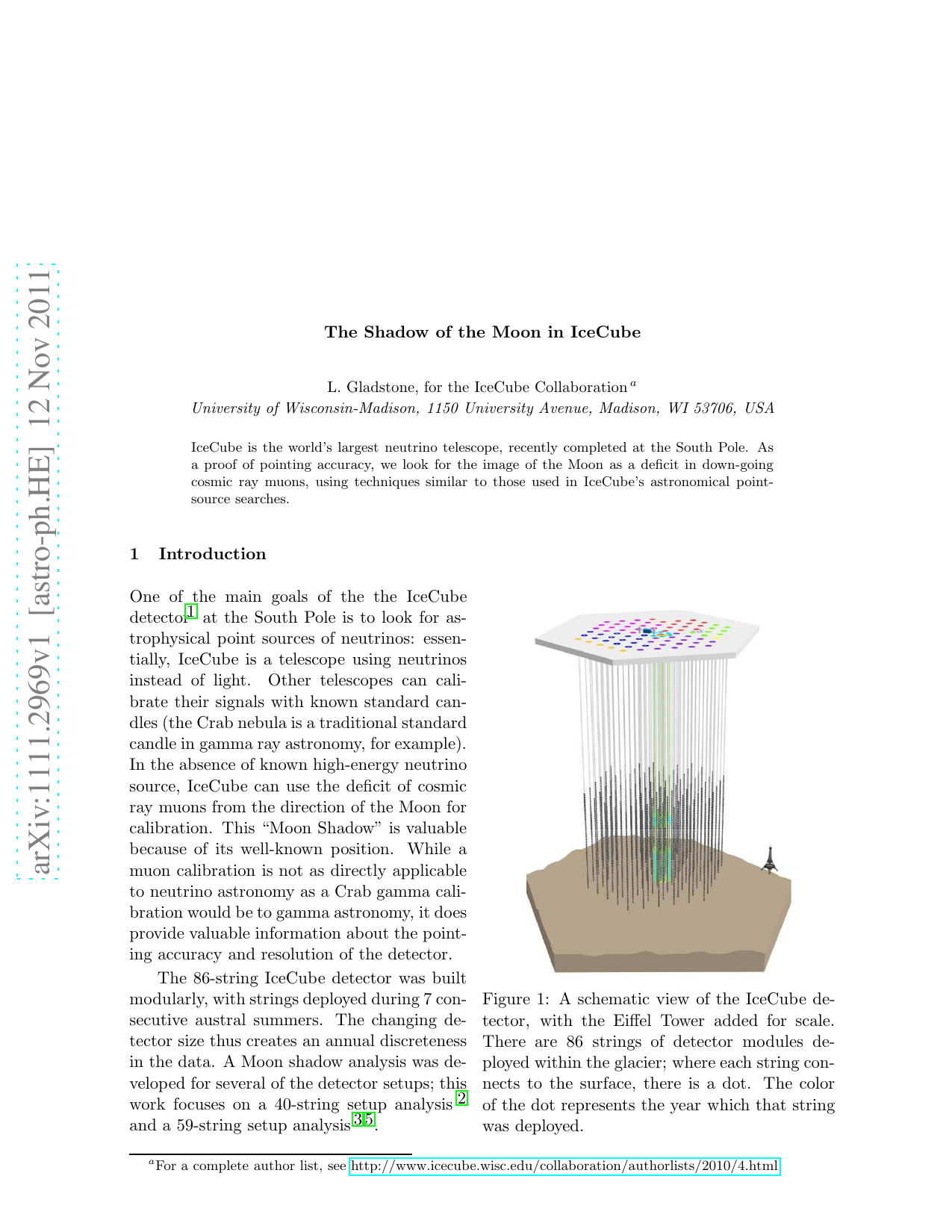

Figure 2: PRELIMINARY: Events in a 1.25◦zenith band around the Moon, using the 40-string

detector setup. A deficit from the direction of the Moon can be clearly seen at 0.

4

Likelihood 59-string analysis

A subsequent analysis3 used data from the 59-string setup of the detector. The approach for

this analysis was similar to the likelihood approach taken for the IceCube point source searches:

an expected signal shape and background shape were developed, and then a likelihood was

maximized at every point in the sky, allowing the number of signal events to vary. The likelihood

formula used is:

L( ⃗xs, ns) =

N

X

i

log

ns

N Si + (1 −ns

N )Bi

where ⃗xs is the position being considered (relative to the Moon), ns is the number of signal

events, N is the total number of events, Si is the expected signal shape, and Bi is the expected

background shape. Note that this has no explicit energy term; this a major difference between

the IceCube Moon analysis and the IceCube point source searches4. For the Moon shadow, we

expect the number of signal events to be negative, as the Moon produces a deficit.

Each event’s contribution to the signal shape was assumed to be gaussian, with a width

given by the estimated error on the reconstructed position.

The background shape was estimated using two off-source regions: to

📸 Image Gallery

Reference

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.