It is a common practice to fix a vertical gnomon and study the moving shadow cast by it. This shows our local solar time and gives us a hint regarding the season in which we perform the observation. The moving shadow can also tell us our latitude with high precision. In this paper we propose to exchange the roles and while keeping the shadows fixed on the ground we will move the gnomon. This lets us understand in a simple way the relevance of the tropical lines of latitude and the behavior of shadows in different locations. We then put these ideas into practice using sticks and threads during a solstice on two sites located on opposite sides of the Tropic of Capricorn.

Fixing the shadows while moving the gnomon

Alejandro Gangui

IAFE/Conicet and Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina.

It is a common practice to fix a vertical gnomon and study the moving shadow cast by it. This

shows our local solar time and gives us a hint on the season in which we perform the observation.

The moving shadow can also tell us our latitude with high precision. In this paper we propose to

exchange the roles, and while keeping the shadows fixed on the ground we will move the gnomon.

This lets us understand in a simple way the relevance of the tropical lines of latitude and the

behavior of shadows in different locations. We then put these ideas into practice using sticks and

threads during a solstice on two sites located on opposite sides of the Tropic of Capricorn.

PACS: 01.40.-d, 01.40.ek, 95.10.-a

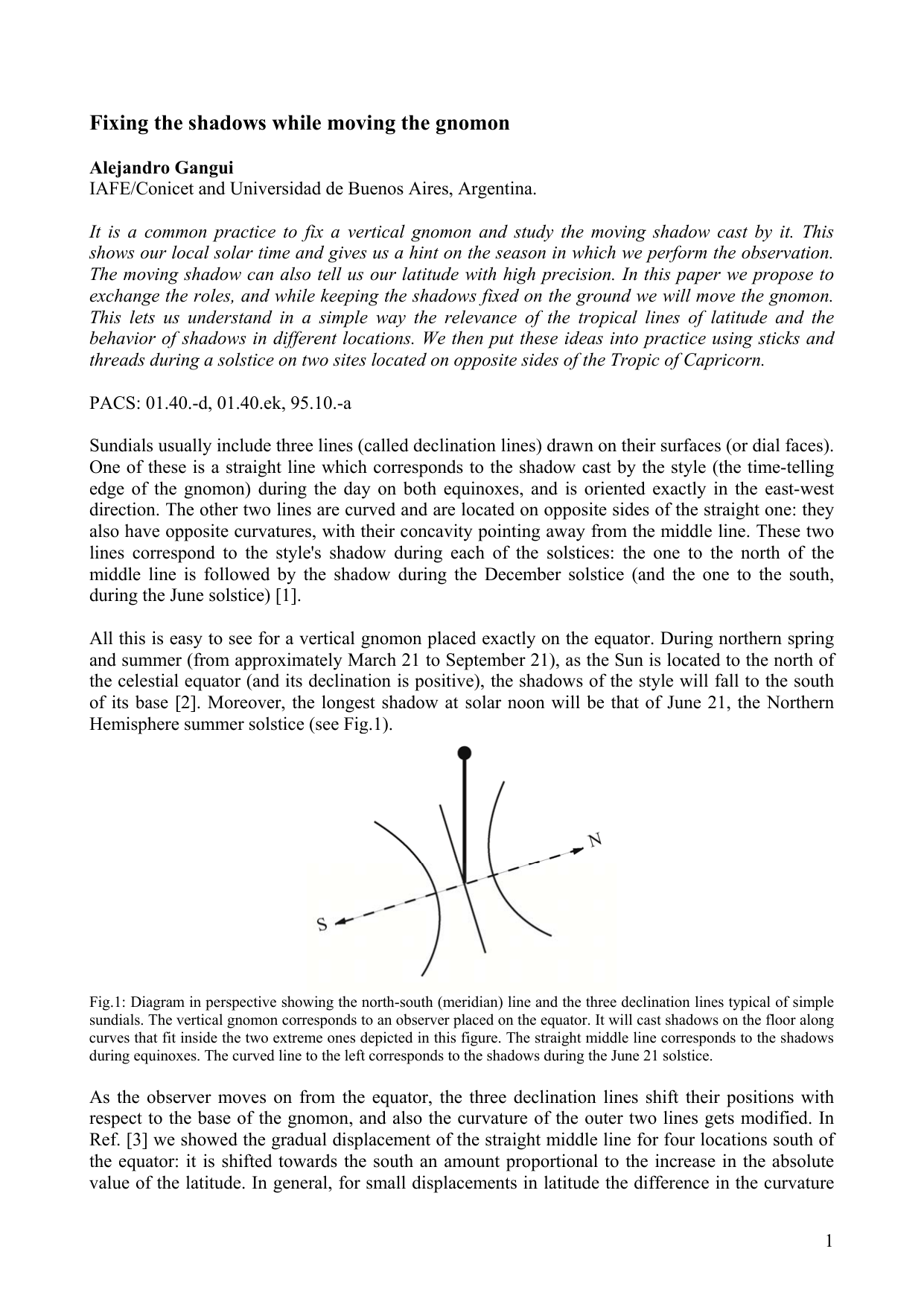

Sundials usually include three lines (called declination lines) drawn on their surfaces (or dial faces).

One of these is a straight line which corresponds to the shadow cast by the style (the time-telling

edge of the gnomon) during the day on both equinoxes, and is oriented exactly in the east-west

direction. The other two lines are curved and are located on opposite sides of the straight one: they

also have opposite curvatures, with their concavity pointing away from the middle line. These two

lines correspond to the style’s shadow during each of the solstices: the one to the north of the

middle line is followed by the shadow during the December solstice (and the one to the south,

during the June solstice) [1].

All this is easy to see for a vertical gnomon placed exactly on the equator. During northern spring

and summer (from approximately March 21 to September 21), as the Sun is located to the north of

the celestial equator (and its declination is positive), the shadows of the style will fall to the south

of its base [2]. Moreover, the longest shadow at solar noon will be that of June 21, the Northern

Hemisphere summer solstice (see Fig.1).

Fig.1: Diagram in perspective showing the north-south (meridian) line and the three declination lines typical of simple

sundials. The vertical gnomon corresponds to an observer placed on the equator. It will cast shadows on the floor along

curves that fit inside the two extreme ones depicted in this figure. The straight middle line corresponds to the shadows

during equinoxes. The curved line to the left corresponds to the shadows during the June 21 solstice.

As the observer moves on from the equator, the three declination lines shift their positions with

respect to the base of the gnomon, and also the curvature of the outer two lines gets modified. In

Ref. [3] we showed the gradual displacement of the straight middle line for four locations south of

the equator: it is shifted towards the south an amount proportional to the increase in the absolute

value of the latitude. In general, for small displacements in latitude the difference in the curvature

1

and relative positions of the outer two declination lines is not drastic, but the directions of the

shadows at solar noon can surprise many of us.

Both teachers and students sometimes think that the equatorial line is the site where astronomical

phenomena change drastically, e.g. where the crescent Moon inverts the orientation of its

illuminated “face” and, also, where Sun shadows point in opposite directions at noon. This

confusion may arise from our habit of speaking in terms of (northern and southern) hemispheres

and from our frequent disposition to contrast what we would see were we living in one or the other.

In the case of the Sun, its location in the sky (its declination) is actually more important for

Astronomy than the terrestrial equator, as we will now see.

Diurnal Astronomy during a solstice

During the 2011 December solstice, in collaboration with colleagues from a few South American

cities, we carried out a joint shadow-observing activity with the aim to emphasize aspects that were

characteristic to each location (like the length of the shadows at noon cast by vertical gnomons)

from others that were common to all cities (like the approximately similar concavity of the solstice

declination line). This activity was a follow up on the one already reported here [3].

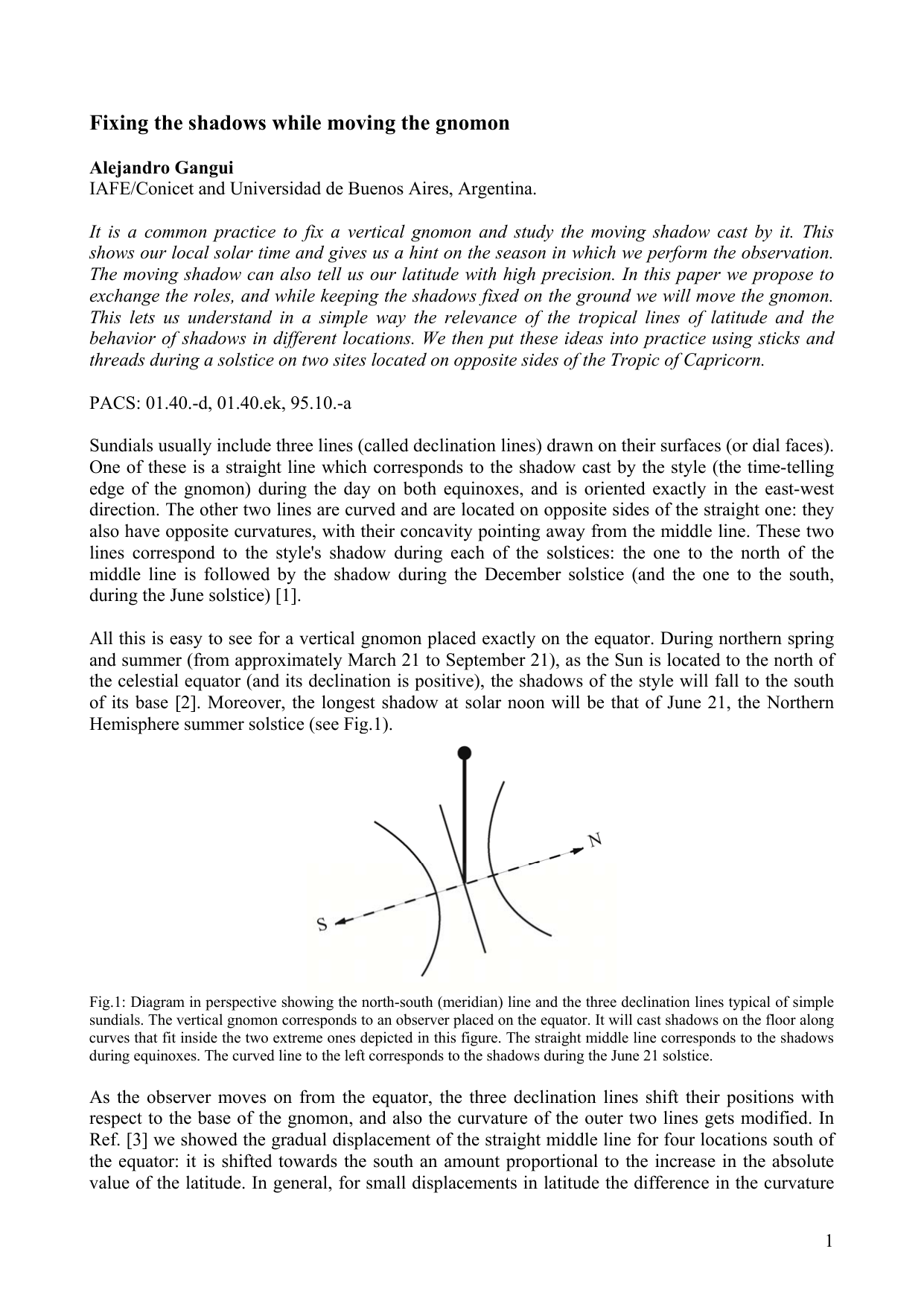

Figure 2 shows two observational settings from different latitudes in Brazil: one in the city of Natal

(Rio Grande do Norte) and the other in Caxias do Sul (Rio Grande do Sul). These cities have the

(geographical) property of being located on opposite sides of the Tropic of Capricorn.

Fig.2: Two observational settings for studying the shadows cast by 1 meter vertical gnomons during the 2011

December solstice. Left image is from Natal (Lat: 5.8°S), while the image to the right is from Caxias do Sul (Lat:

29.2°S). Theoretical values for the angles between the gnomon and the solar noon threads (the shortest ones) are 17.7°

= |5.8°-23.5°| for Natal, and 5.7°

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.