In these three lectures I discuss the present status of high-energy astroparticle physics including Ultra-High-Energy Cosmic Rays (UHECR), high-energy gamma rays, and neutrinos. The first lecture is devoted to ultra-high-energy cosmic rays. After a brief introduction to UHECR I discuss the acceleration of charged particles to highest energies in the astrophysical objects, their propagation in the intergalactic space, recent observational results by the Auger and HiRes experiments, anisotropies of UHECR arrival directions, and secondary gamma rays produced by UHECR. In the second lecture I review recent results on TeV gamma rays. After a short introduction to detection techniques, I discuss recent exciting results of the H.E.S.S., MAGIC, and Milagro experiments on the point-like and diffuse sources of TeV gamma rays. A special section is devoted to the detection of extragalactic magnetic fields with TeV gamma-ray measurements. Finally, in the third lecture I discuss Ultra-High-Energy (UHE) neutrinos. I review three different UHE neutrino detection techniques and show the present status of searches for diffuse neutrino flux and point sources of neutrinos.

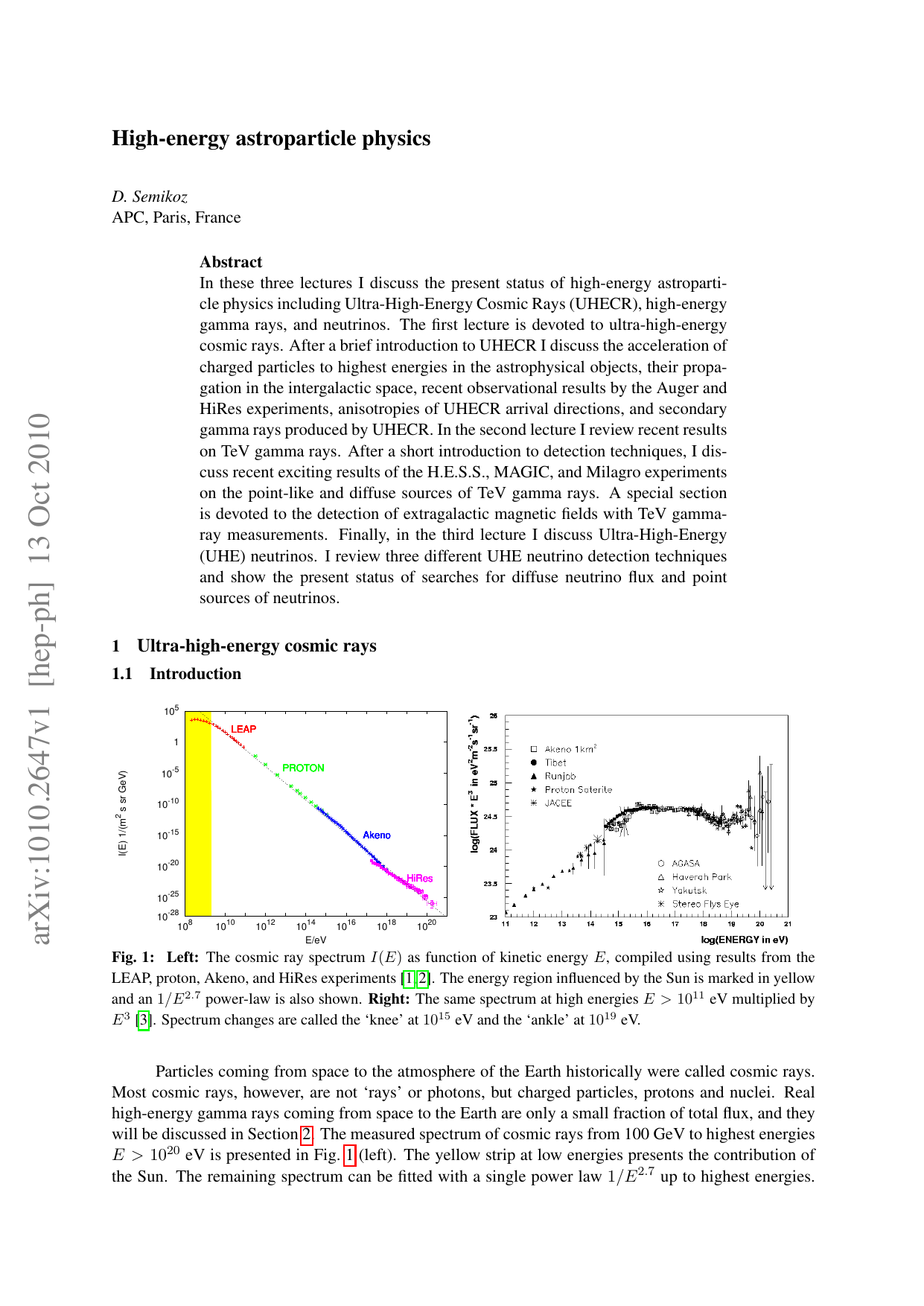

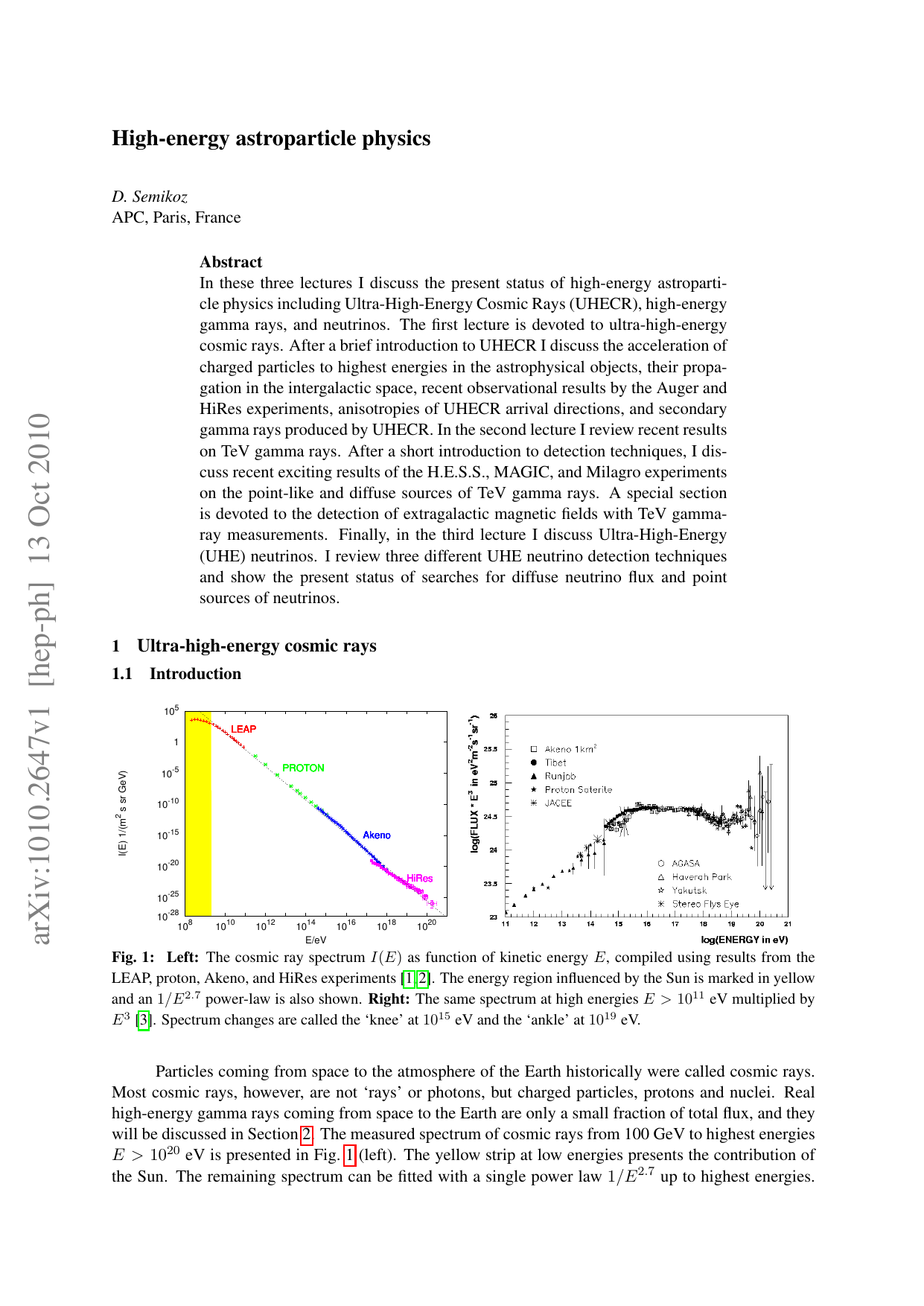

1 Ultra-high-energy cosmic rays The cosmic ray spectrum I(E) as function of kinetic energy E, compiled using results from the LEAP, proton, Akeno, and HiRes experiments [1,2]. The energy region influenced by the Sun is marked in yellow and an 1/E 2.7 power-law is also shown. Right: The same spectrum at high energies E > 10 11 eV multiplied by E 3 [3]. Spectrum changes are called the 'knee' at 10 15 eV and the 'ankle' at 10 19 eV.

Particles coming from space to the atmosphere of the Earth historically were called cosmic rays. Most cosmic rays, however, are not ‘rays’ or photons, but charged particles, protons and nuclei. Real high-energy gamma rays coming from space to the Earth are only a small fraction of total flux, and they will be discussed in Section 2. The measured spectrum of cosmic rays from 100 GeV to highest energies E > 10 20 eV is presented in Fig. 1 (left). The yellow strip at low energies presents the contribution of the Sun. The remaining spectrum can be fitted with a single power law 1/E 2.7 up to highest energies.

The main contribution to it above 100 GeV gives galactic sources. After multiplication of the spectrum on the energy cube, one can see changes of power law in Fig. 1 (right). At E > 10 15 eV the spectrum becomes steeper. This change in the spectrum called the ‘knee’ and associated energy E = 10 15 eV is the maximum energy up to which galactic sources accelerate cosmic rays. The next change of the spectrum is located at E = 3 • 10 18 eV and has two possible interpretations. Either this is the place where extragalactic sources start to dominate or it is the result of pair-production energy loss by extragalactic protons (see Section 1.3). At the end of the spectrum there is a cutoff, which was not seen in the old experiments presented in Fig. 1 (right) due to small statistics, but it was observed recently by the HiRes [2] and Auger [4] experiments.

In this lecture I briefly discuss the theory and observations of Ultra-High Energy Cosmic Rays (UHECR), the highest-energy particles measured on Earth with energy E > 10 18 eV. Such particles, protons and nuclei, can be accelerated in astrophysical objects, propagate through intergalactic space, losing energy in the interactions with Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB). UHECR are charged particles. Therefore they are also deflected in the Galactic and intergalactic magnetic fields on the way from the source to the Earth. For a more detailed introduction to UHECR I recommend recent lectures by M. Kachelriess [5].

There are several important scales commonly used in astroparticle physics. Distance is usually measured in parsecs, 1 pc = 3 • 10 18 cm. Corresponding larger units are kiloparsec 1 kpc = 10 3 pc and megaparsec 1 Mpc = 10 6 pc. Energy at highest energies is usually expressed in units of EeV = 10 18 eV.

The plan of this lecture is as follows. In Section 1.2 I shall discuss possible acceleration mechanisms of cosmic rays and astrophysical objects which potentially can be their sources. In Section 1.3 I present the main energy loss processes for UHECR particles and briefly discuss their deflection in the magnetic fields. In Section 1.4 I sum up recent observational results from the Pierre Auger Observatory and other experiments. In Section 1.5 results on anisotropy at highest energy are discussed. In Section 1.6 I review expectations on secondary photons and neutrinos from UHECR protons. Results are summed up in Section 1.7.

There are several possible acceleration mechanisms that can work in astrophysical objects. These include first-order Fermi acceleration on the shocks in plasma or acceleration in the potential difference, which we call one-shot acceleration below. However, in any case, the Larmor radius of a particle does not exceed the accelerator size, otherwise the particle escapes from the accelerator and cannot gain energy further. This criterion is called the Hillas condition [6] and sets the limit

for the energy E gained by a particle with charge q in the region of size R with the magnetic field B.

The maximum energy of the accelerated particle can be restricted even more than required by Eq. ( 1) if one takes into account energy losses during acceleration. Unavoidable losses come from particle emission in the external magnetic field, which can be either synchrotron-dominated if the velocity of the particle is not parallel to the magnetic field, or curvature-dominated in the opposite case.

In Fig. 2 in the plane magnetic field versus acceleration region size, the Hillas condition Eq. ( 1) is shown by a thick black line. The left figure is for protons and the right one for iron nuclei. Possible acceleration in different astrophysical objects is shown with thin solid figures. Notations are the following: NS are neutron stars, GRB are gamma-ray bursts, BH are black holes, AD are accretion disks, jets are jets in active galaxies, K and HS are knots and hot spots in the jets, L are lobes of radio galaxies, clusters are cl

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.